Published in The Australian, 14 August 1995, p. 15.

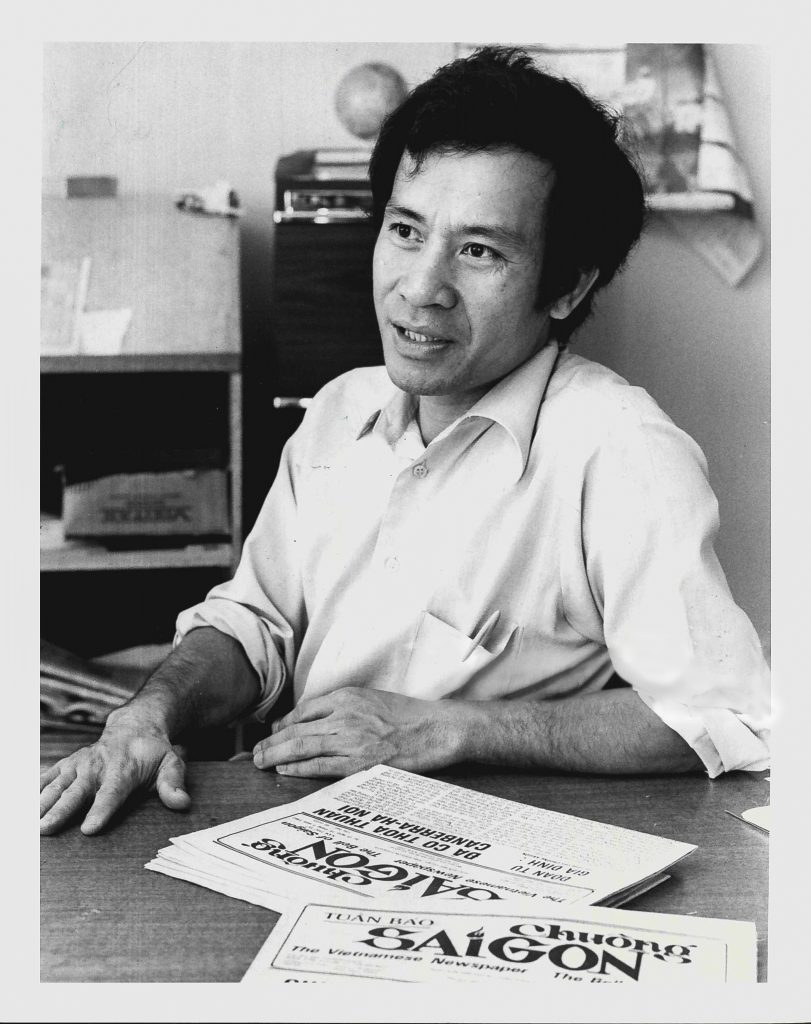

I first met Hop Van Chu, as he then called himself, in 1984 when the then Opposition spokesman for immigration and ethnic affairs, Michael Hodgman, made some dramatic criticisms of Asian immigration to Australia. This was met with surprise and fear in large sections of this country’s Vietnamese community. The Labor Council of NSW’s George Miltenyi thought that developing contacts with the Vietnamese community might be useful, and so a meeting with ALP and Labor Council people was organised at a restaurant in Cabramatta.

Chu Van Hop was key to organising this meeting in 1984: as an Immigration and Ethnic Affairs Department bureaucrat, he wanted it to be both a low key but important milestone along the path of forging closer links between all the major political parties and the Vietnamese community.

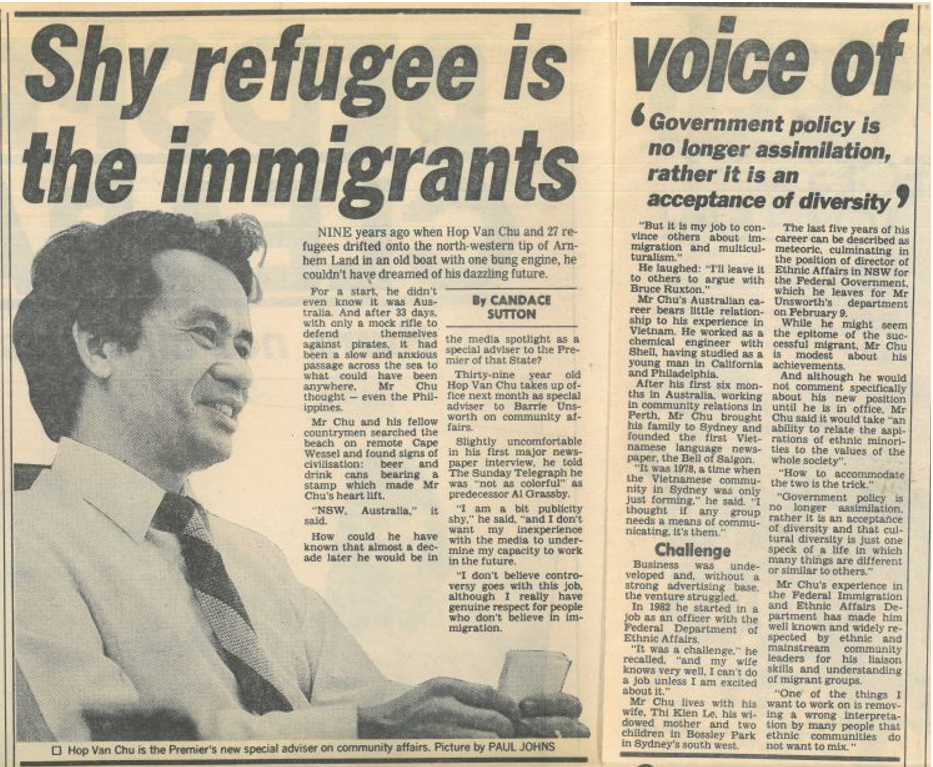

Out of this grew a deepening political involvement, which led to friendship between Hop and Barrie Unsworth. Hop later became his principal adviser on ethnic affairs when Unsworth was premier.

Hop was always full of ideas, insights, and original turns of phrase. The politician he admired most was Paul Keating and I remember him speculating about why the then Treasurer’s verbal expressions were so often sparkling and evocative. Not having been constrained by the deadening effect of academic routine and “rigour” in thought and argument, Hop decided, was a big plus. The street fighter’s skills were something with which he readily identified.

Hop was born in North Vietnam but moved south with his family when he was a boy. He attended high school in Saigon and then won a scholarship to the United States. When he was a chemical engineering student in Philadelphia, he became disillusioned with the then South Vietnamese regime. How could a war be worthwhile and morally defensible when your side was led by such corrupt and mediocre characters? But at no stage was he a communist or in any way sentimental about the Vietcong.

He returned to Saigon in 1973, then after the communists won power he was arrested and sent to work in a re-education agricultural centre.

However, he managed to escape a year or so later, on a makeshift boat. He came to Australia as a refugee, guided by a compass in a Bata shoe. In my school days I remembered the novelty of such shoes but for Hop they were no toy. On the boat out of Vietnam they were vital to his survival.

He came to love this country passionately – and this was later expressed through attaining citizenship.

Rather than pursuing his engineering profession, Hop decided to establish the first Vietnamese language newspaper in Australia, the weekly Bell of Saigon which began in 1979.

He felt a need to write about his experiences, including his naivety about the promise of the “New Vietnam” where hundreds of thousands were in detention and thousands died as political prisoners. He sold the paper a few years later.

Hop then tried his hand at a few business ventures before joining the Immigration and Ethnic Affairs Department as an ethnic affairs officer in 1982. Rapid promotion followed, commensurate with his talents as a communicator, listener, and advocate of post-arrival services – including the adult migrant education and language program.

In 1985, Hop became the Director (Ethnic Affairs) of the NSW Office of the Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs. When he was appointed special adviser on community affairs to NSW premier Barrie Unsworth in 1987, his new role was even praised by the Opposition spokesman on ethnic affairs, Jim Samios.

In a practical as well as a symbolic sense, Hop’s appointment epitomised the success of the settlement and refugee program.

After the defeat of the Unsworth government in 1988, Hop returned to business – trying his hand at many activities. He set up a business for remittances by Vietnamese in Australia and the US of money to their families in Vietnam.

I remember once taking him to a meeting with Sir Peter Abeles. Hop wanted to discuss air links with Vietnam and the creation of a new airline. Unfortunately, nothing came of this idea.

It was hard to keep up with someone with so many new ideas. Was he impulsive and lacking the discipline of a truly successful entrepreneur? It was hard to tell.

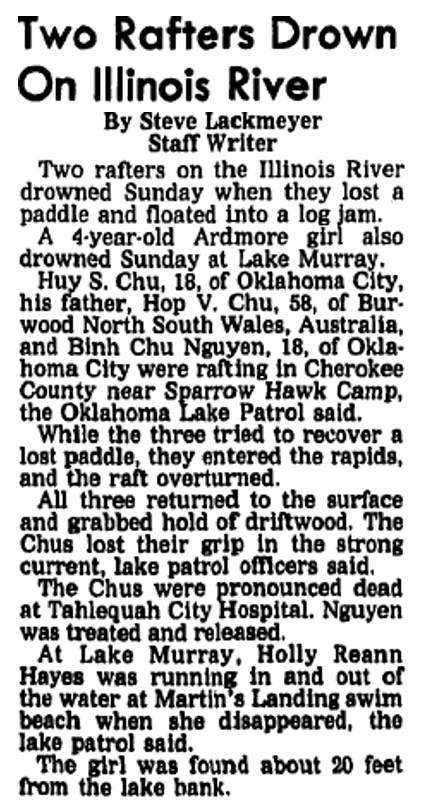

He went to the US recently to meet with his son whom he had sent to Oklahoma to study. Hop was supposed to then travel to New York to sign an agreement between the AIG company (one of the largest insurers and finance houses in the world) and his merchant bank (which he had recently formed) based in Vietnam.

Tragically, both Hop and his son drowned in a canoeing accident on the Illinois river. Chu Van Hop was a great Australian. He is survived by his wife and daughter.

Postscript (2020)

I only knew of Chu’s death over a month afterwards. I am grateful to Imre Salusinszky for getting this belated obituary published in the first place. I have corrected a few typos and made minor changes to the reproduction above.

Chu Văn Hợp (18 July 1947-4 June 1995) also known as Joseph Chu Van Hop, who suggested he be called Hop Van Chu when I knew him, was a thoughtful, entrepreneurial and engaging intellectual, journalist, bureaucrat, and businessman, whom I came to know from the early 1980s up to his premature death by drowning in 1995.

Based on conversations with family members, Tuong Quang Luu, a mentor of Chu in Australia, says that Chu was born in 1947 at Quí Cao Village, Tứ Kỳ District of Hải Dương Province (near Hanoi) in the northern part of the then unified State of Vietnam with Saigon as its national capital. The researcher Hai Hong Nguyen, however, says he was born in Hai Phong about 50km away). His headstone where he was buried in Sydney, to add confusion, records his birth as in Vĩnh Ninh, a rural district in Quảng Bình province, which is further south of Hanoi, considered the “mien trung” or middle part of Vietnam, though 50 km north of the 17th parallel, the provisional military demarcation line between North and South Vietnam established by the Geneva Accords of 1954.

I am relying on Quang Luu’s biographical notes in capturing the early details of Chu’s life.

Apparently, Chu’s father, Mr Chu Văn Hòa, died when he was a toddler. In 1954 with Vietnam divided under the Geneva Accords, his mother, Mrs Nguyễn Thị Vi, a devout Catholic along with 600,000 of her co-religionists, fled communist North Vietnam, with her only child, 7-year-old Chu. They eventually found a new life in Saigon.

Chu was sent to the Jesuit Đắc Lộ College for his education and, finishing schooling, succeeded in highly competitive examination for entry to the University of Saigon’s Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Mrs Chu’s hopes that her son might pursue religious training for the priesthood faded. During his second year, Chu won a scholarship to pursue medical studies in the USA. But, instead, he decided to switch to a BS in chemical engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

After graduation, he visited Western Europe and Australia before returning to Saigon in 1973 taking up a role at the head office of Shell-Vietnam. Even then, he intimated to a cousin, Mrs Chu Thị Hiệp, that Australia would be his first choice if ever he had to choose between America, Europe, or Australia.

Chu was one of Shell’s managers in Saigon when South Vietnam fell to the North Vietnamese Army at the end of April 1975. He thought the regime would need his skills, so his thoughts did not immediately turn to fleeing.

As Quang Luu summarised:

In a sense at least initially, he was not wrong. He was not rounded up into the so-called re-education camps. Instead, he was re-employed in a lesser position at a nationalised Shell branch office outside metropolitan Saigon.

However, as communist cadres learned their way around, Hợp’s position became less tenable to the extent that in 1978 he decided to flee the communist regime.

Indeed, as he told me, a brief spell of indoctrination frighted him. Chu fled with his wife Lê Thị Kiêm and their 1-year old son by boat, the compass from the sole of a Bata shoe (a brand I knew from my school days) helping him navigate; he eventually made it to Perth in 1978, settled in Sydney, joined the Federal Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs and rapidly ascended its ranks. From 1987-1988 he was principal adviser on community and ethnic affairs matters for the Premier of NSW, and he then returned to business.

Chu was one of the Australian Vietnamese community’s high-achieving migrant success stories. Along with his friend Tuong Quang Luu — a barrister and former South Vietnam diplomat credentialled to Australia, a refugee who rose to be head of the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Radio, who was also proficient in English and expert in Western mores — Chu was a star in a struggling Indo-Chinese community.

There were nine phases of Chu’s life: growing up in Vietnam, including his family moving south; after winning a scholarship, tertiary education in the US; return to Vietnam and taking on various senior management roles, including as an engineer, 1973-75, with Shell Oil in Saigon; endurance and survival under the communist regime from 1975-78, including “re-education” at a labour camp in rural Vietnam; escape with his wife Lê Thị Kiêm and son, and survival as a refugee; arrival in 1978 in Perth and settlement in Australia and activities in business, including from 1979-82 as publisher, editor, and co-founder of the Bell of Saigon/Chuông Saigon newspaper in Sydney; emergence and endeavours as a senior bureaucrat in the Federal Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs from the early 1980s, including from 1983-4 Assistant Director of Community Affairs, 1984-5 Director of Community Affairs, and from 1985-87 Director of Ethnic Affairs with the NSW office of the Department; a brief stint as a political adviser, as Community Liaison Officer with the Premier of NSW, Barrie Unsworth, from 1987-1988; and activities to re-establish himself as a businessman, including in fostering Australian and Vietnamese economic ties between 1988-1995, including writing a book published in 1991 on doing business in Vietnam.

This leaves out his personal story as son, husband, and father (including to a daughter born in Australia), as well as his religious views, about which I know little.

He came to my attention due to a series of accidental events that can draw disparate people close. In this case, my personal sympathy for Vietnamese refugees in Australia, and a connection with someone who knew him, George Miltenyi, and events and controversy on Australian immigration policy brought us together.

Sympathy for Refugees

Growing up, I had a vague sympathy for South Vietnam. The Brothers and some other teachers at Marist Brothers Penshurst explained in religious education and social science classes that communism was an evil force and that just as the West (Australian troops included) fought off communist aggression in divided Korea in the early 1950s, there was a moral duty to protect the south, where maybe 10% of the population was Catholic, and where many had fled religious persecution in the north. The analysis was a little simple, but that is what I remember how the position was described at school.

Conscription in Australia for Vietnam began in 1964 and ended in 1972; my schooling in 6th form (Year 12 in today’s parlance) finished in the same year. Whitlam came to power on 2 December 1972 (I was already a “dewy-eyed Whitlamite”), and full Australian withdrawal from the conflict, already winding down, thereafter took place. President Nixon in early 1973 spoke about “peace with honour” and equipping and enabling the South Vietnamese to defend themselves. This was called “Vietnamisation”, with scaled back American and allied support.

The Vietnam conflict, by the time my twin brother and I had come of age, was not a particularly potent issue at the 1972 election. That year for a school magazine I wrote a sentimental poem on the perils and tragedy of war, alluding to Vietnam. I was not thinking too deeply. In my defence, I was still a child! Conscription was no longer a personal jeopardy. In America, partially enabling narrow win of the US presidency at the 1968 election, Richard Nixon promised to end conscription; by the end of 1972, this had occurred.

At university I studied politics. In one of my courses on Australian Foreign Policy under Associate Professor Owen Harries in the School of Political Science at the University of NSW, I wrote about Australia’s leading anti-Vietnam war critic, Dr Jim Cairns. I concluded that the Menzies government never should have introduced compulsory military service (conscription was not needed as there were enough volunteers). This measure added a poisonous, emotional element to the debate.

I read about the ‘Nixon Doctrine’ announced in July 1969. As Nixon said: “… we shall look to the nation directly threatened to assume the primary responsibility of providing the manpower for its defense.” Nixon bought himself time to implement what came to be called ‘Vietnamisation’ whereby South Vietnam would be equipped and trained to fight the war. Everyone seemed exhausted by the War. No new, grand strategic ideas were enunciated in Australia, even though from 1969 onwards most Australians favoured withdrawal from Vietnam. What self-reliance or greater reliance under the American security umbrella meant was debated. But in 1972-75, this was not a particularly potent electoral issue in Australia.

I was wary of the “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, dare to struggle, dare to win” chants at Moratorium rallies. Not that I attended any. I knew of them from the television, the newspapers and, especially, the Labor-leaning Brian White afternoon show on Sydney radio station 2GB. Appreciation of arguments against conscription was one thing; identification with a communist dictatorship in the north was something else entirely.

I was not radicalised by Vietnam, I came to political awareness after the peak of the anti-war movement, and I was vaguely in the camp of “right to resist communist aggression, poor execution strategy” and “conscription is an own goal” school of thinking. I thought argument about the conflict merely being a civil war was exceptionally naïve.

In April 1975 just before Saigon fell, there was a big student meeting at the University of NSW expressing solidarity with the people of Vietnam and expressing hope that the Whitlam government might take an interest in the human rights abuses that were already apparent. Speakers predicted more killings and more stories of arbitrary arrests and persecution would inevitably emerge. Barbarities including revenge killings usually happen after a ‘civil war’ and always after a successful communist insurgency. There were estimates of hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing and there were pleas about the need for Australia to look after those who worked with Australian troops. I found this meeting on campus moving and disturbing. (The university Democrat Club, associated with the National Civic Council, organised the meeting. I knew none of the organisers. I was just one person in a crowd, listening. There was merit in a good deal of what they outlined as a humanitarian crisis.)

In Max Hastings’ magisterial and encyclopaedic assessment, Vietnam (2018), he refers to the privations of, cruelty to, and lording over the vanquished by the North:

In the year following ‘liberation’, some three hundred thousand South Vietnamese were detained. All those with the slightest association with the fallen government were branded, tainted for life: while the cashier at Saigon’s Majestic Hotel escaped imprisonment, he was denied further employment and repeatedly interrogated, because he had accepted payment for so many bills from Americans. Approximately two-thirds of detainees, including all ex-officers, were dispatched to re-education camps where they remained for between three and seventeen years. A record of opposition to the Thieu regime provided no immunity: Among those confined was the Buddhist monk Tri Quang, who had created such embarrassments for Saigon’s generals.

And thereafter follows an even greater litany of crimes against humanity. Is it any wonder that so many of those who could fled? The Hastings book’s sub-title is “An Epic Tragedy 1945-1975.” The loss of life was horrific. Forty Vietnamese to every American died. US blunders and atrocities matched by those committed by their enemies.

By 1975 I was emerging from my intellectual chrysalis into a liberal Cold War social democrat. Whatever might be the truth of Gough Whitlam’s alleged statement that he did not want “yellow Balts” in Australia, I was broadly sympathetic to the refugees. I saw no inconsistency then or now in both holding such a position and a Labor-aligned political outlook.

Viviani in The Indochinese in Australia 1975-1995, From Burnt Boats to Barbecues references the first wave of Vietnamese immigrants who fled in 1975, as typically those tied to the old regime who feared reprisals. The second wave, 1976-78, included those who despaired at the continued persecutions, resentful at the northerners continued hounding of southerners. For well-educated, business-trained Vietnamese, the decision by the regime in March 1978 to close private businesses suggested there was no or a limited role for them in the “new Vietnam”. Subsequent migrant waves included family reunions and orderly settlement from camps, including refugees who left in the 1980s and early 1990s.

The Labor Council of NSW

From the late 1970s, I was working at the Labor Council of NSW, the co-ordinating, peak body of the unions in NSW. In early 1983, I knew we needed to replace our Ethnic Affairs Officer (a position then jointly funded by Federal and NSW government grants). The incumbent wanted to move onto greener pastures and there was a need to scout for someone suitable. One Saturday I turned up for a seminar on the Adult Migrant Education Service (AMES) at the Tom Mann Theatre in the Amalgamated Metal Workers Union Building in Chalmers Street near Central Station. (In those days, I spent a great deal of my “spare” time trying to follow migration matters and linking up with people whom I thought might have policy insights. Curiosity was a key requirement of my job at the Labor Council. I was also secretary of the NSW ALP education committee at the time, and I needed to know more about how the AMES operated.)

The issue of the “mentality” of Vietnamese refugees came up (with the usual contorted discussion on whether they were “real” or “economic” refugees.) Some, not all, in the audience were sceptical of the bona fides of refugees from Indo-China, believing many of them were economic migrants, using the collapse of South Vietnam as a convenient excuse to hop on a boat and then be accepted as a genuine refugee. Sometimes this attitude went hand-in-hand with a sympathetic view of Vietnamese “nationalist” communism. At the AMES meeting, one person got up, exasperated by some of the audience’s scepticism of Vietnamese migrants, and pleaded that they were like most people: they wanted to get ahead and provide the best for their children. Our job, now that they were here was simple: to help them succeed.

I introduced myself to him, George Miltenyi. He was brave to stand and address a suspicious crowd. He seemed clearly knowledgeable about migration services and came across as a passionate advocate. I discovered he worked in the Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affair’s NSW office, had trained as a social worker, presented as a person likely to be sympathetic to Labor, and was of Hungarian origin (so, surely, anti-communist). I saw his potential as the Labor Council of NSW’s next Ethnic Affairs Officer. Following various discussions, several months later there was an interview with Labor Council Secretary Barrie Unsworth and independent panel member Paolo Totaro (a former head of FIAT car company in Australia, turned NSW bureaucrat) who agreed that Miltenyi was best for the job. He worked at the Labor Council from June 1983 to February 1986.

“Asianisation”

Unexpectedly, in early 1984, less than a year after the election in March 1983 of the Hawke Labor government, there was a debate about immigration and the so-called Asianisation of the Australian migrant intake. This led me to really get to know Chu.

Michael Hodgman, the Liberal Shadow Immigration Minister, known as “the mouth from the south” for his love of undisciplined, provocative statements, provided a thought bubble on Australia’s changing immigration intake. With close to a majority of Asians among new migrants, he suggested that the Opposition could pick up a dozen seats on the issue. In March 1984, Geoffrey Blainey, addressing a Rotary Club meeting at Warrnambool, stupidly weighed into the issue as did various dog-whistling politicians. Hodgman complained that the Labor government’s immigration policies were becoming “positively anti-British and anti-Commonwealth.” This went on throughout 1984 with some small-l Liberals, including Ian MacPhee, a former Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, and Philip Ruddock, a future Minister for the same portfolio, opposing Hodgman’s rhetoric and supporting the Labor government’s stance (which was the previous Fraser government position) in favour of a non-discriminatory, “colour blind” selection policy. (MacPhee and Ruddock also took a similar position when in 1988 the then Liberal leader John Howard publicly toyed with the “question” of Asian immigration.)

The “debate” was ugly and, understandably, the Indo-Chinese including leading members of the Vietnamese community were worried. Family reunion was an important means for separated families to be reunited. It looked like Hawke and Labor would lead Australia indefinitely in the 1980s. Yet relations were weak between the Vietnamese community and Labor. Community leaders actively moved to improve the situation (and also with the Australian Democrats).

In his period first as Shadow Minister and then as Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Mick Young reached out to the Vietnamese community and promised fairness with respect to refugee and family reunion, and a continuation of settlement services. Tuong Quang Luu, by then the Department’s NSW state director, stated that: “Mick Young as a backbencher [and Shadow Minister] made every effort out of his busy time to set up contacts with the Vietnamese community through voluntary workers like the late Mr Chu Van Hop and myself…” Some suspicions about Labor were evaporating.

George Miltenyi knew Chu. And together they came up with the idea of fostering better relationships between the Vietnamese community and NSW Labor. After all, outside of the extreme Left, Australian Labor figures were anti-communists too. Some of the old NSW Labor Right union leaders had expressed support for Australia’s contribution to the war (if not to conscription. I remember Jim Gibson, the President of the Labor Council from 1981 to 1984, and Secretary of the Glassworkers’ Union, telling me as much.) The Vietnamese migrant footprint in the broader labour movement including trade unions was beginning to be felt. For example, in the Postal Workers Union, a “swing union” oscillating from right to left and back, there was a large Vietnamese presence in the Redfern mail exchange, for example, and they mostly voted for moderate Labor people, helping to rout the Left in the union.

In one of his many articles on the history of Vietnamese settlement in Australia, Tuong Quang Luu comments that:

As it happened, the Vietnamese followed the same footsteps of many previous waves of settlers. They tended to live in less well-off suburbs surrounding migrant hostels, their first point of contact in Australia. If the Vietnamese were indeed “Asian Balts”, this social and economic distribution turned many of them around to become Labor voters.

The Vietnamese mostly settled in the western suburbs of Sydney – in Cabramatta, Mt Pritchard, Canley Vale, and Campsie – in strong Labor-voting areas. Local councillors and politicians needed to win their votes: Friendship, cultural connection, dialogue and linkages, as well as assistance and communal appreciation, were all a necessary part of the story.

Some wonderful aspects of the melting-pot were present — interaction, engagement, and assimilation. Concepts, however, such as the melting pot, assimilation, and multiculturalism receive a bad press nowadays. They were once innocent phrases, though different emphasises by different people were placed on them. At one extreme is the idea of melting away all differences to realise some bland commonality. But who really thought that? Australia was and is a land that celebrates variety — the dominant, Anglo-Celtic population combined Australian nationalism with pride and celebration of English, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh cultures. There was also a desire to ensure all felt some sense of solidarity with each other. The Australian-Vietnamese story is one of integration and love of origin, the cultivation and retention of heritage – and tension associated with the mix. Les Murray in his poem “Immigrant Voyage” captures in an earlier time the tension, especially for younger new arrivals, the “New Australians”, fitting-in:

Ahead of them lay

The Deep End of the schoolyard,

Tribal testing, tribal soft-drinks,

And learning English fast,

The Wang-Wang language.

Ahead of them, refinements:

Thumbs hooked down hard under belts

To repress gesticulation…

But all that is a wider topic than what can be covered here.

‘How Labor Buried the Refugee Hatchet’

In 1984 George and I enlisted Bob Carr to join us to visit a restaurant at Cabramatta with Chu and Vietnamese community leaders. Carr was well known from his stint from 1978-84 as a senior journalist with The Bulletin magazine and, after a by-election in October 1983, was then the NSW state MP for Maroubra under Premier Neville Wran. Carr was an articulate anti-communist Labor person who clearly understood that Indo-Chinese refugees deservedly had no illusions about the racket of Leninist-Stalinist-Chi Minh communism.

The lunch time meeting one Saturday in July 1984 went extremely well. We decided that we would organise further catch ups and eventually with senior Labor figures, including senior MPs and union leaders.

In October 1984, NSW Premier Wran, several State Cabinet ministers, union and party officials, met over dinner in the President’s Dining Room, Parliament House, Macquarie Street, Sydney, with 13 Vietnamese community organisations, with several speakers saying that the night was “a truly historic occasion.” Johno Johnson, the President of the Legislative Council, was the host. This was the first such gathering of state Labor and Vietnamese community leaders since Vietnamese settlement began in the 1970s. This previously unthinkable gathering was due to a significant shift in political feeling on both sides.

How had this come to pass? In January 1985, Sydney Morning Herald reporter Peter White observed that:

According to one member of the Vietnamese community, the Liberals “took the Vietnamese for granted”. Another important factor was … Professor Geoffrey Blainey-inspired immigration debate coupled with statements at the time by members of the Federal Liberal Party which appeared to the Vietnamese community to be headed in an anti-Asia direction. The Vietnamese community saw a possible threat to the family reunion program and anti-discriminatory immigration, settlement and even employment and education policies. According to one Vietnamese community leader, the community felt humiliated.

White gave credit where credit was due, noting that: “The NSW Labor Council’s Ethnic Affairs officer, Mr George Miltenyi, approached community leaders and a meeting with Labor Party and Labor Council officials was organised in July to be followed by the dinner held at Parliament House…” George knew that the timing was right. I am certain, as a senior public servant, that Chu was scrupulous in not attending the dinner with Premier Wran, but his fingerprints were everywhere in organising the rapprochement.

I am not sure why a triumphalist article in the mainstream media appeared so early in the forging of a new relationship. The party office insisted. Some people love to brag. The story was shunted down the line to the Ethnic Affairs reporter in the paper; White quizzed Miltenyi on what had transpired.

My brother, Shane Easson, remembers the function: Wran was a little tipsy and arrived late with his son Glenn. One of the Vietnamese participants articulated a point that Chu sometimes made which was that “the Vietnamese were the Irish of Asia.” By this he meant that unlike the English and Chinese, the Vietnamese were not great traders or colonists, but like the Irish who were driven out of their land by the potato famine, the overseas Vietnamese were forced out by the imposition of a foreign ideology. Wran became so enthused by this remark that without bidding he promised to build in Cabramatta a boat museum to commemorate those who had endured the hardships of arriving to Australia. Unfortunately, his promise was not delivered. But in 1987, when Hop was in Premier Barrie Unsworth’s office, he persuaded the premier, as part of the bicentenary, to build a boat museum in Cabramatta and this was publicly promised. In 1988, however, after Unsworth’s defeat, a new premier renounced the proposal which was never revived.

All we have left of Unsworth’s commitment is the fact that in 1990, the Australian Maritime Museum purchased the Tu Do (meaning “Freedom”), a boat from Vietnam which arrived loaded with refugees in Darwin in 1977. The boat was originally painted sky blue to blend into the ocean and to evade authorities and the notorious Thai pirates who preyed on boat people. Nam Le’s story The Boat describes one refugee in the dead of night spotting her rescue vessel:

They saw it ahead, barely visible in the weird, weakly thrown light from the banks. An old fishing trawler, smaller than she’d imagined — maybe fifteen metres long — sitting low in the water. It inched forward with a diesel growl. A square pilothouse rose up from the foredeck, a large derrick-crane straddling its back deck, and the boat’s midsection congested with short masts and cable rigs.

Not all the boats were the same.All were makeshift, adapted for the journey of escape.

Recalling our time getting to know Chu over 35 years later, Miltenyi remembers that Chu loved ideas and discussing them: “He was much better suited as a diplomat, journalist, liaison officer, bureaucrat, advisor than a businessman. Ideas and engagement with people trumped focus on business and the discipline to execute.” He was magnetic through the breadth of his vision for Australia and Vietnam. Indeed, his own personal journey to Australia did not define his identity as it did with so many others. The journey to Australia was just that, a journey. He was a refugee but that is not how he defined himself. He was cautious and contemplative, perhaps borne out of having to survive in Vietnam – he never changed that part of his character. Though a dynamic presence, he somehow was also a serious character. He would talk little about his family, being a very private man. A part of him always looked forward, he lived for the future, almost dismissing reminiscence as a waste of time. Hop thought the political integration of the refugee communities was essential to their true integration into Australia. He rose above the political divides of the Vietnamese community.

In the mid-1980s, I got to know Chu better, catching up with him for lunchtime and other chats either over a meal or at my office, frequently with my brother Shane (then working as Research Officer at the NSW ALP Office), with Miltenyi often joining. We usually met at a Vietnamese restaurant in George Street (I cannot remember the name), diagonally across the road from St. Peter Julian’s church in the Haymarket. I learnt about Phở dishes, Phở bo (a beef noodle dish) made with extra coriander being a favourite, and Canh Cha Ca (fish cake soup), Hấp, and other dishes. As I never ate pork, he steered me clear, and would espouse the virtues of different regional cuisines and, as well, the fusion of French and Vietnamese influences.

Chu loved chatting about all topics under the sun, including politics. At university in the United States he saw and better appreciated the limitations, corruption, and vulnerabilities of the South Vietnamese government, but he was never remotely tempted to communist sympathy. We discussed that.

(In hindsight, America’s best chance of a stable non-communist Vietnam probably ended with the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem in October 1963. Ho Chi Minh supposedly said that he could scarcely believe the Americans would be so stupid. Prior to becoming leader of South Vietnam in 1954, Diem enjoyed a deserved reputation as an independence leader. In 1933, at age 32 he became Interior Minister of Vietnam, a post Ho Chi Minh again offered him in 1946, but resigned after three months following the French rejection of his proposal for a Vietnamese legislature as part of a path for full independence. Thereafter, he was the key non-communist independence leader.

There are some striking similarities between Diem and Syngman Rhee who in 1948 became the first President of South Korea. Diem was Catholic, the other a Protestant, unusual in mainland East Asia, although Chiang Kai Shek also converted to Christianity in the late 1930s. Both were fierce anti-communist nationalists fighting against colonial rule by the French in one, the Japanese in the other. Rhee had campaigned against the Japanese from 1895. Both were indisputable counterweights to the notion that communism provided the only realistic alternative to colonialism. Both were authoritarian rulers of corrupt regimes, but still far better than the communist alternative.)

In the entry for “Chu, Van Hop” in the AustralAsian Who’s Who (1986) he lists his hobbies as “reading, social and political affairs.” I can attest to the truth of that! He was interested in the use of language by politicians, seeing Hawke as an authentic character. Even if the latter’s speech-making was sometimes stilted, when speaking off-the-cuff Hawke was uncommonly captivating. Very unlike the cliché-ridden phrasing of most politicians. If only I had a dollar for every “shoulder to shoulder”, “we stand here together” and similar dreary expressions!

Keating’s turns of phrase, he thought, were assisted by an earthy education. If Keating had attended university would he be as interesting, he wondered. The Australian poet Bruce Dawe saw that language, the wonder of expression, needed to be fluid. As he says in ‘Easy Does It’:

I have to be careful with my boy,

that I don’t crumple his immediate-delivery-genuine-fold-up-and

-extensible world

into correct English forever, petrify its wonder

with the stone gaze of grammar…

Chu understood his meaning.

I got Chu to meet Barrie Unsworth. On the 22 January 1987, the new NSW Premier announced his appointment as his Special Adviser on Community Affairs. The Premier noted that in Chu’s previous role, as Director of Ethnic Affairs in New South Wales for the Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, he was responsible for a range of post-arrival services and programs, including citizenship, the Adult Migrant Education Program, the Grant-in-Aid Scheme, the Migrant Workers’ Rights Scheme, the Migrant Resource Centre Program, the Migrant Project Subsidy Scheme, the Bilingual Information formation Officer Program, Sydney’s Westbridge Migrant Centre, and language services.

This rollcall of activities under-scored Chu’s extensive expertise and seasoned background.

Strategic Thinker

In the transcript of an interview the year before (in 1986) with Judith Winternitz, on immigration and migrant matters, Chu gives the impression of an accomplished, experienced leader. There he discussed the refugee programmes (not only for the Indo-Chinese); the treatment and policies towards refugees in camps across the globe, including in Asia; the selection of refugees; the immigration process from arrival to settlement; government involvement in settlement and education; family migration; voluntary groups and their work with refugees; government programmes and objectives for refugees; problems experienced by refugees; and Australian society’s long term acceptance of Vietnamese immigrants. In this perceptive interview, Chu suggested that there were long-term, if presently obscure, benefits ahead:

My view is that Australia has its past linked to Europe, but its future interests lie in the [Asia] Pacific and the presence of the Vietnamese, possibly theoretically, philosophically, sociologically, helps or equips Australia with a better capacity to tackle its future, than it was before. But this is a challenge… you have to compromise the past with the future. And how you do it is something that is very difficult. But I think, from what I can judge, the political leadership seems to have the courage and have the vision to do it.

This analysis underscored Chu’s strategic and forward-thinking mind.

With Unsworth, he worked on policy and programmes for all ethnic communities, not just his own. The bicentennial celebrations led to various programmes and commemorations of the contributions of the people from many nations who came to Australia. For example, Chu assisted in getting government funding support for the Phước Huệ Temple at Wetherill Park in Sydney. He worked on electoral policy and ethnic community strategy for the Unsworth government in the lead-up to the March 1988 state elections.

Chu was sometimes portrayed in the media as shy and measured.

After Unsworth’s defeat as Premier of NSW in March 1988, Chu was out of a job, and started fossicking for new lines of work and creative endeavour.

Before turning to the next phase of Chu’s career, it is interesting to recall the zest with which he led his life in Australia.

Challenges and Projects

I heard a story about Chu in 1979 driving across the Nullabor from Perth to the east, family in tow, arriving in Sydney to forge links with the much larger Vietnamese community there, meeting with Tuong Quang Luu, badgering and exciting him and others with ideas and opinions. Throughout his life Chu sought out mentors and advisers, tested his ideas, and pursued challenges and business projects. He was entrepreneurial.

On the emergence of a local Vietnamese media, Tuong Quang Luu highlights Chu’s role, meeting with him in Canberra and at the Lan Saigon Restaurant on Pitt Street in the Sydney CBD, or at a nearby bookshop managed by Mr. Trần Phước Hậu, who “like Chu Văn Hợp”

… had an eye on business and he detected a real need of reading material for newly-arrived Vietnamese. He imported Vietnamese books and Vietnamese-English and English-Vietnamese dictionaries which had been published in Saigon and re-printed in California for sale in the emerging market of Sydney. Dictionaries were indeed popular, but Chu Văn Hợp believed the need for information was more acute than cultural maintenance. He wanted to publish a newspaper.

From this idea and after consulting with many friends, according to Quang Luu, Chu wanted to ensure that what he visualized would resonate with potential readers who were in urgent need of information and cultural and social readjustment. The title Bell of Saigon/Chuông Saigon was finally chosen to indicate the newspaper’s non-communist stand, as the name of the capital of undivided Vietnam from 1949 and of South Vietnam from 1954 to 1975 would send a clear message. Chu Văn Hợp also hoped to provide a forum for the voiceless refugees whose memory of persecution and poverty under the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) and the horror of their escape remained fresh and emotionally raw. Right from the start, he was careful enough to feature certain community figures whose anti-communist views could not be questioned.

The title of the publication also asserted the paper’s position on freedom of faith, because chuông, “bell”, is a common religious instrument for the Vietnamese Christian and Buddhist denominations. Saigon as a city was re-named Ho Chi Minh City by the communists. The Bell of Saigon sounded a defiant tune in more ways than one.

Jim Kable was one contributor to the publication. He was a teacher who had undertaken a Summer School Viet-namese language course at the Australian National University in January 1980 and was teaching English as a second language (ESOL) at Cabramatta High School and then at the Cabramatta Hostel AMES Centre — while also studying via the University of New England (UNE), Armidale, for a Graduate Diploma in Multicultural Studies. He explained: “I was undertaking this for no promotional or salary increment — merely as a kind of personal public service — to welcome older Viet-namese refugees to my class, to maybe draw some comparisons between the structure of English and Viet-namese…” In 1980 Kable was introduced to Chu and PHAM Ngoc Cuong at the paper when he sought permission to undertake a survey of the Bell of Saigon readership for a media studies assignment as part of his UNE diploma. Chu gave his approval, afterwards asking Kable to write a weekly column on aspects of Australian life. He did so for a year, contributing each week between 800 and 1200 words — which Chu or one of his colleagues translated.

Another early contributor, again according to Quang Luu’s recollection, was Mr Nguyễn Vy Túy who recalled:

None of us had any training in journalism or media production. The first team consisted of Mr. Chu Văn Hợp as editor, Mr. Đỗ Lê Viên as chief of staff and myself as technical producer and we were equal in our ignorance. But Chu Văn Hợp was clever in his decision to rent a room at Seddon Street, Bankstown NSW where other more established ethnic papers were located. We often talked with our unsuspected colleagues to learn their technique on the spot and at times we stayed back ‘to spy’ on their work.

As a business venture, the paper was commercially unsuccessful, but it was ground-breaking and an incubator for future development of Australian-Vietnamese media.

New Business Opportunities in Vietnam

After Labor’s defeat in the 1988 NSW election, Chu took on a few Federal government advisory roles, but increasing focused on trade and business opportunities between Australia and Vietnam. Some background to the gradual emergence of a more market-friendly Vietnamese socialist economy is worth telling because this became Chu’s new long-term focus.

By the late 1980s, the Vietnamese communist political leadership had limited economic options. They had won the war between north and south in 1975, but at great economic cost. The inauguration of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in 1976 enshrined the doctrine of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” in the constitution — a purist ideological dead-end. In rebuilding and vitalising a moribund economy, a brain-drain of talent, with over a million Vietnamese people, many of the educated elite, secretly escaping the country either by sea or overland during 1975/8, added to the country’s woes. The determination of the communists in the south to discipline, re-educate, imprison, and in some cases, execute former opponents, meant continuing turmoil.

In the first week of 1979, the Vietnamese Peoples’ Army (VPA) launched a full-scale armed invasion of China-ally Kampuchea (Cambodia), led by the murderous Khmer Rouge who killed between 1.5 to 2 million people, around 25% of the country’s population in a mad campaign, Ground Zero, to re-start the country. The Vietnamese action incited the Chinese to invade Vietnam. Though repulsed, the 27-day war with China from 17 February 1979 wrought devastation. Vietnam’s third constitution, modelled on that of the USSR, written in 1980, declared that the Communist Party was the only party to represent the people and to lead the country. Luckily for the Vietnamese people, the hard Stalinism with Vietnamese characteristics which characterised the party from the 1950s had by now moderated to a nasty authoritarianism.

With limited options (poor relations with China, a crumbling Soviet Union drastically reducing economic aid), Vietnam began tentative market reforms along the model inspired by Deng Xiaoping in China. The south, with a ‘remembered’ tradition of trade and commerce, led the way. The desperate perestroika policies of Mikhail Gorbachev in the USSR inspired the Vietnamese leadership to consider a new ideology and practical economics of a “socialist-oriented market economy”. The dissolution of the Soviet empire in December 1991 led old enmities to weaken. In the immediate aftermath there was a thaw in the long hostile Sino-Vietnamese relations (which did not last long).

In 1989, Chu drew close to Mr Chấn Hưng, a successful businessman of Chinese-Vietnamese background and they explored the potential for business dealings, notwithstanding frustrations with arrogant party cadres in the former Saigon.

Chu’s mind turned to writing a book on the changing situation in Vietnam. If he could obtain a credible publisher, he might be considered an authority. In his Guide to Doing Business in Vietnam (1991) published by noted legal publishers CCH International, Chu declared that Vietnam is “a future tiger” and that in writing the book: “My ambition is to facilitate better understanding between Vietnam and its new business partners overseas. The information contained in this book has been drawn from information publicly available up to June 30, 1991.”

The book starts with background, including three Chapters on cultural, historic, geographic, and political matters, introducing the policy formulated by the Party in 1986 and reaffirmed in 1991 known as Đổi Mới (“renovation”). It proceeds to analyse and translate official policies and legislation. John Gillespie in a review, praised the book for its clarity and stated it is “the first text to cover such a wide range of issues relevant to the foreign investor.” But he cautioned that:

What is not said in the text… is that there are considerable political tensions at the highest level in the Communist Party. As a result, interpretation and administration of commercial laws tend to vary according to the political predilections of the authorised ministries and/or provincial-city administrators.

Chu understood those risks but reasoned that some trends were clear, and that the regime now understood its survival depended on “opening up”. Diel noted in an assessment of Vietnam’s economic liberalisation to 1992 that: “The State monopoly in external trade has been opened, but strict licensing procedures for private trading companies prevent free competition with foreign suppliers,” and attributed that assessment to Chu. This was to acknowledge both the subtlety and insight of Chu’s analysis of the changing situation in his homeland.

Thirty years later John Hancock AM, a former Partner of Baker & McKenzie law firm based in Bangkok, who Chu acknowledged for his assistance in producing the book, recalled:

I got to know Chu Van Hop in the early 1990s while I was working on Vietnamese matters out of Bangkok and preparing for the set-up of a Baker & McKenzie office in Hanoi in anticipation of the lifting of the US Embargo. I can clearly visualise him. Lovely fellow. I had quite a few meetings with him and we traded information on developments related to investment laws and other aspects of doing business in Vietnam, and he very kindly asked me if he could recognise me in his publication.

Chu thanked him in finishing the book.

Chu argued:

The emergence of a market economy legal framework is taking shape. Business interaction between Vietnam and other countries is increasing and becoming more diversified. Further signs were expressed at the last Congress (seventh) of the Vietnamese Communist Party in June 1991 reaffirming the steady reforms which will now be accelerated. The resolutions passed by the Congress guarantee the private sector against nationalisation and requisition; relax the rules on land use; and speed up the development of a legal framework for a market economy.

The country could not afford to be diplomatically isolated. Post publication, Chu thought that the unfolding of events meant even better prospects for doing business in Vietnam.

International negotiations in which Australia played a major role, with the then Secretary of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs, Michael Costello, supported by his minister, Gareth Evans, instrumental to the final result, led to the Paris Agreement on Cambodia which resolved the conflict in October 1991 and temporarily, for the first time, led to the United Nations taking over as the government of a state. The agreement was signed by nineteen countries. This enabled Vietnam to establish or re-established diplomatic and economic relations with most of Western Europe and various ASEAN countries. In February 1994, the United States lifted its economic embargo against Vietnam, and full diplomatic relations were established in June 1995.

With exciting business opportunities opening, I know Chu felt frustrated at the lethargy and conservatism of leading Australian business identities about exploring Vietnam options. As my obituary of him said, I introduced him to Sir Peter Abeles (1924-1999). I think this was in 1992, before Abeles stood down later that year as CEO of Ansett Airlines. Chu was hoping that just as Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) sponsored and supported Thai Air in its early days, an Australian airline might do the same with Air Vietnam. (In 1960 Thai Airways was formed as a joint venture between SAS and Thailand’s domestic carrier.) I kept the memo Chu prepared for Sir Peter.

1989 Memo to Sir Peter Ables, Ansett Airlines: A Strategic Opportunity in IndoChina:

Additionally, Chu realised how fraught would be the process of Vietnam’s “opening” to the world. He decided to pursue contacts with the Party bureaucracy in Hanoi.

Miltenyi recalls flying to Vietnam in April 1989 to set up a professional tourism/visa service between Vietnam and Australia. The idea was to facilitate Vietnamese citizens to easily visit relatives in Australia. On arriving, Miltenyi was greeted by a broom stick across two wooden poles, which was the immigration post at the Ho Chi Minh City international airport. The visit was a disaster as some of his contacts in Vietnam were concerned for their safety and failed to turn up at the airport: “Prior to that adventure I sought Hop’s advice, who of course was very encouraging, supportive, and saw potentials that I never considered. His far-reaching intellect foreshadowed today’s education, tourism, and general trade with Vietnam. We were going to be the vanguard…” But the difficulties were too great, the move too early. They were dreamers.

When we last met in 1995, Chu’s soon-to-be-signed AIG (American Insurance Group) agreement was front of mind. Chấn Hưng’s advised Chu to sell all of his share of a recently obtained investment banking license to the New York-based AIG for a price of US$5m, with AIG retaining him in a managerial position for 5 years with an annual salary of US$132 000, provided he would submit a business plan at the time of signing the deal in New York.

Death

The night before flying to America, Chu spent the night before his departure at Chấn Hưng’s home, discussing strategy and, among other things, presciently he asked Mr and Mrs Chấn Hưng to continue looking after his aged mother who lived by herself nearby in Cabramatta.

We agreed to catch up on his return from the United States. Chu was excited, mentioning he was flying to Oklahoma to celebrate with his son, Huy Sơn Chu, who had just finished his schooling; having settled after a rocky time in Australia.

The Oklahoman in early June 1995 reported that two rafters, father and son, drowned when canoeing near Sparrow Hawk Camp, in Cherokee County, on the Illinois River. They lost a paddle and floated into a log jam, overturned in the rapids, grabbed onto driftwood, but lost their grip in the strong current. A young man, Binh Chu Nguyen, presumably a friend of theirs, survived after recovering in hospital.

As Quang Luu discovered, friends headed by Chấn Hưng raised more than twenty thousand dollars to bring the bodies home and arrange the funeral. True to their promise, Mr and Mrs Chấn Hưng, and the Rev Father Joseph Nguyễn Quang Thạnh, looked after Hợp’s mother, Mrs Nguyễn Thị Vi, financially and spiritually for another 5 years before her death.

I never had contact with or was able to be in touch with Chu’s wife or daughter. Perhaps in the trauma and rush of putting everything together, transport home and burial, with Chấn Hưng taking control, this is why Vĩnh Ninh, instead of Quí Cao Village or Hai Phong appeared on the Chus’ headstone.

Hop Van Chu, the man I knew, was one of those fascinating people whose soft speaking voice when combined with my partial deafness made it sometimes difficult to hear and to carry out a conversation, without a quiet setting, and some exhaustion on my part. But his charisma and goodness outweighed the difficulty.

In the decades after I committed myself to full-time business enterprise, I missed him even more. We might have learnt so much from each other.

References:

Entry for “Chu, Van Hop”, in AustralAsian Who’s Who, edited by Jasbeer Singh, Oriental Publications, Adelaide, 1987, p. 242.

Australian Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Review of Activities, No. 407 of 1987, Appendix A: Some Significant Events, 1986-87, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1987.

Bruce Dawe, Sometimes Gladness. Collected Poems 1954 to 1997, Fifth Edition, Longman, South Melbourne, 1997.

Chu Van Hop with special assistance from John Hancock, Guide to Doing Business in Vietnam, CCH Australia Limited for CCH International, North Ryde [Sydney, Australia], 1991.

Markus Diehl, Real Adjustment in the Economic Transformation Process: The Industrial Sector of Vietnam 1986-1992, Kiel Working Paper, No. 597, Institut für Weltwirtschaft (IfW), Kiel, 1994.

Peter Edwards, A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965-1975, Allen & Unwin in association with the Australian War Memorial, 1997 (one of the volumes in the series The Official History of Australia’s Involvement in South East Asian Conflicts 1948-1975.)

Tom Frame, Phillip Ruddock and the Politics of Compassion, Connor Court Publishing, Redland Bay [Queensland, Australia], 2020.

Brian Galligan, Political Review, Australian Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 3, 1984, pp. 292-301.

John Gillespie, Review of Chu Van Hop’s Doing Business in Vietnam, International Business Lawyer, Vol. 20, March 1992, p. 163.

Max Hastings, Vietnam. An Epic Tragedy 1945-1975, William Collins, London, 2018.

Hai Hong Nguyen, Chu Van Hop forever remembered as founder of the first Vietnamese newspaper, Chuông Sài Gòn (the Bell of Saigon), among Vietnamese communities in Australia, unpublished manuscript, 2019.

John G. Keilers, Nixon Doctrine and Vietnamization, US Army Military History Institute, posted 29 June 2007, https://www.army.mil/article/3867/nixon_doctrine_and_vietnamization, accessed 30 May 2020.

Steve Lackmeyer, Two Rafters Drown on Illinois River, The Oklahoman, 5 June 1995, p. 16.

Nam Le, The Boat, Penguin Books, Camberwell [Victoria, Australia], 2008.

Tuong Quang Luu, The 40th Anniversary of Vietnamese Settlement: Vietnamese Language Media in Australia, VCA/NSW, 40th Anniversary of the Resettlement of the Vietnamese Community in Australia 1975-2015, Sydney, 2015, https://quangduc.com/a58057/40th-anniversary-of-vietnamese-settlement-vietnamese-language-media-in-australia, accessed 20 December 2019.

Tuong Quang Luu, The 40th Anniversary of Vietnamese Settlement: Vietnamese Buddhism in Australia: Development in Changes and Challenges, https://quangduc.com/a31124/the-40th-anniversary-of-vietnamese-settlement-vietnamese-buddhism-in-australia-development-in-changes-and-challenges, accessed 20 December 2019.

Tuong Quang Luu, Four Decades of Resettlement: The Vietnamese in Australia – A Brief Historical Review, updated version of the author’s presentation on the same subject at the Whitlam Library on Saturday 8 October 2016, as part of the NSW City of Fairfield’s Heritage Program of the year, https://quangduc.com/a29626/four-decades-of-resettlement-the-vietnamese-in-australia-a-brief-historical-review, accessed 22 December 2019.

Les Murray, Collected Poems, Black Ink, Carlton, 2018.

Philip G. O’Brien, The Making of Australia’s Indochina Policies Under the Labor Government (1983-1986): The Politics of Circumspection?, Australia-Asia Papers No. 39, Griffith University Centre for the Study of Australian-Asian Relations, Nathan [Queensland, Australia], 1987.

Michael Sexton, War for the Asking: Australia’s Vietnam Secrets, Penguin Australia, Ringwood [Victoria], 1981.

Tim Soutphommasane, The Asianisation of Australia, Keynote Speech to Asian Studies Association of Australia Annual Conference, “AsiaScapes: Contesting Borders” at the University of Western Australia, 10 July 2014, The Asianisation of Australia? | Australian Human Rights Commission, accessed 12 January 2020.

[Unknown], Champion of Vietnamese Boat People, Herald Sun, 15 August 1995, p. 55.

Nancy Viviani, The Long Journey; Vietnamese Migration and Settlement in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton [Victoria, Australia], 1984.

Nancy Viviani, The Long Journey; Vietnamese Migration and Settlement in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton [Victoria, Australia], 1984.

Nancy Viviani, The Indochinese in Australia 1975-1995: From Burnt Boats to Barbecues, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

Peter White, How Labor Buried the Refugee Hatchet, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1985, p. 7.

Interview

Judith Winternitz interview with Chu Van Hop, 27 February 1986, recorded by the Sydney Team — Indochinese Refugees of the Cultural Context of Unemployment Project, a CEP Program administered by the National Library of Australia, NLA ORAL TRC 2010 S/83 (transcript) 55pp.

Email Communications:

Shane Easson, 22 May 2020.

John Hancock, 23 April 2020, & 21 May 2020.

Jim Kable, 24 March 2020 & 18 May 2020.

Tuong Quang Luu, 17 September 2020

George Miltenyi, 18 May 2020.

Nancy Viviani, 29 May 2020.

Assistance: Various librarians, National Library of Australia.

Postscript (2021)

The ADB published Hai Hong Nguyen’s entry in late 2020: ‘Chu, Van Hop (1947–1995)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chu-van-hop-29917/text37037, published online 2020, accessed online 11 April 2021.