Review of Mark Aarons The Family Files, Black Inc., Collingwood, 2010, published in Quadrant, Vol. 54, No. 9, September 2010, http://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2010/09/red-confession-with-a-twist/

Mark Aarons’s book The Family Files is a red confession with a twist. He tells his story and that of three generations of the Aarons family’s activity at the highest levels of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) with the aid of a unique documentary source: the 209 files, wire-tap transcripts and reports of the Australian security services in the National Archives. Aarons has written an interesting, honest assessment. He drops some bombshells about ALP/CPA double ticket-holders, about union election fraud, “Moscow gold” funding, and about tensions and ideological differences and splits within the CPA.

Surprisingly, Aarons says that “for the most part ASIO’s work was conducted within a largely democratic framework”, though he criticises the organisation for “crossing the line” between spying and politics. He would say that. Yet he also contrasts the experience in Australia with that in the countries of “really existing socialism”.

It is very reassuring that ASIO’s mountain of files indicates a thorough diligence to keep tabs on the enemy. It seems that, from the late 1940s, at every level of the Communist Party, in every office there was a spy or some willing informer.

Such intense surveillance was in Australia’s national interest. As is now well known, the Venona Project – the top secret collaboration of the US and UK intelligence agencies in deciphering Soviet cables from various locations around the world – revealed in the late 1940s that there was a spy network in Australia. In response, Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley established ASIO.

Mark Aarons, by reference to ASIO files and tapes made by his father, Laurie, conclusively establishes that the secretive, leading CPA operative Wally Clayton organised the spy ring. Clayton blurted this out in a tape recorded by Laurie Aarons in 1993. This is the most impressive section of the book – a true unravelling of a mystery.

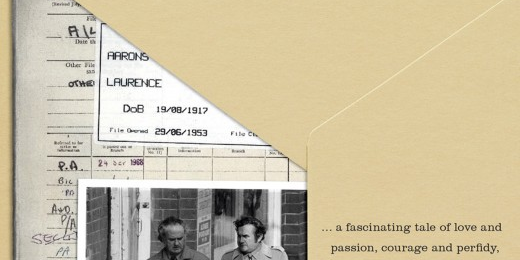

The photographs are telling: one shows Laurie Aarons in earnest discussion with Tito; in another you can almost smell the Peking duck at a meal with Zhou Enlai. Then there are the ASIO pictures from its files – many with the same, drab brick background: marking the comings and goings from Red headquarters.

Aarons questions the whole communist project from start to finish. The psychosis wore off once the world got more and more prosperous, as the old social democratic idea of civilising, not overthrowing, capitalism became the only option for true democrats.

When I started working at the Labor Council of New South Wales thirty-two years ago, John Ducker and Barrie Unsworth insisted that each Wednesday, at 10.00 a.m. sharp, I drop down to the CPA bookshop in nearby Dixon Street to buy the latest copy of Tribune, the weekly CPA newspaper. In it would be the issues the Left would raise at Thursday night’s Labor Council meeting. It is hard so many years later to explain or convey an era when communist sympathy had so much potency.

Aarons’s book has wider implications and more narrow ones too. Most media attention has focused on the ALP/CPA double ticket-holders. Bob Carr has written – in the Spectator and in the Australian – that Aarons’s book provides justice to the DLP and the New South Wales Right and their depiction of a compromised ALP Left.

I am sceptical of the all interpretations in the ASIO files. Only through documentary evidence and corroboration are points proven. The history of the ALP is not established through the partial glimpse through an ASIO keyhole or a Communist Party file.

I doubt that Bruce Childs was a double ticket-holder. Tom Uren, I think, certainly was not. During the early 1950s, Tom Uren was not yet radicalised. His far Left sympathies came after the Split. Yet he was extremely close to Laurie Aarons, as is established in the book. The idea that John Wheeldon toyed with becoming a communist senator sounds and is fanciful. Yet, at different points (Wheeldon later became fiercely anti-communist) they all accepted the leading role of the CPA in “the broad Left”; foremost, it seems, the Aarons brothers, Laurie (Mark’s father) and Eric provided Marxist-inspired theoretical leadership to many in the ALP Left. Arthur Gietzelt loved nothing better than to talk Marxism.

Of those named in the book, Senator Gietzelt was probably a communist – and a double ticket-holder. Aarons refers to the “Hughes-Evans” Labor Party in New South Wales which absorbed the CPA after illegality in 1940. Progress was their organ. Notoriously, the “Hands off Russia” resolution at the 1940 New South Wales ALP Conference was the last straw. Federal intervention followed. Bill McKell once told me how shambolic the ALP was prior to winning the New South Wales election in 1941.

The Labor Party in New South Wales had to be reinvented in 1941. Eventually after the 1941 ALP Unity Conference – bringing together the different splinter ALP groups – Hughes and Evans lost power. Both were double ticket-holders. I once looked up volumes of Progress newspaper published in the 1940s. There were references to “sapper” Ray Gietzelt. Arthur organised CPA activity in the Returned Soldiers’ League —which expelled him in the late 1940s.

What insights does the book have for other interpretations of Australian communism? The most scholarly account is Stuart Macintyre’s mostly fond reverie Reds.

Macintyre’s book was written in a spirit of sentimental thinking – that the party was a wonderful, progressive force. That although “mistakes” were made and the excesses of Stalinist apologetics deserved an earnest frown and condemnation, the golden years of the party were from 1968 onwards – after the condemnation of the Soviet invasion of the Czechoslovakia. Macintyre’s own radicalism coincided with the New Left/humanist Marxism and the rediscovery of “the young Marx”.

Macintyre has written some fine books – A Proletarian Science, for example, is an insightful classic about the impact of Marxism and communist ideas in Britain in the first quarter-century after the Bolshevik revolution. But the scholarly achievements of Reds are let down by the lack of a more brutal assessment of the comrades.

The conservatives, liberals and social democrats who fought in the unions, in public institutions and coalesced in journals like Quadrant are vindicated in this book. Aarons deserves credit for facing the truth through evidence gleaned from a treasure trove from Australia’s democratic domestic spies. In an unusual way, this book is their tribute.

Postscript (2017)

I found this book by Aarons rewarding to read; he conscientiously and carefully assessed a lot of material, revealing the nuances and detail of relationships that were pivotal to the influence of the CPA and his family in Australian communism. I knew him slightly when he worked on the staff of Labor Premier Bob Carr. Refreshingly, he thought about issues. By then, though from a part of the left lacking some appreciation of the movement he was now a part of, he fitted in the ALP mainstream.