Notes “dipped” into in delivering remarks at the Whitlam Institute, Western Sydney University, on 21 February 2023 at the launch of Scott Prasser & David Clune, editors, The Whitlam Era. A Reappraisal of Government, Politics and Policy, Connor Court, 2023.

My Dad thought Whitlam was like Reg Gasnier playing for Dubbo United. The perfect player let down by his side. That is not entirely right. Gasnier never played “blinders” every game. Whitlam was also human. But the analogy points to one reason for this book: A deep, informed, critical appraisal of the Whitlam era, the aspirations and performance of the man and his government. Fifty years after his election as prime minister, from reflection and reckoning, we can gain perspective on a time when Australia really did change.

Congratulations to the editors – Scott Prasser and David Clune. Being a good editor is more than inviting authors to write chapters. They organised discussions between contributors, prodded everyone to reflect on alternate explanations, invited anonymous referees to review chapters. This book covers almost everything major. It is a great read.

About the person, humour and self-effacing whimsy were never far away. Three examples.

When someone earnestly asks if I have read this or that important document, I sometimes respond with a Whitlamism: “No comrade, but I have extensively glanced at it.”

As Malcolm Fraser drifted unmoored from past political allegiances, becoming Public Enemy Number One of the Liberal Party, the two former protagonists shared a podium. Looking at him, Gough remarked that for the second time Fraser had dislodged him. But he was handling rather better this time the repositioning “compared to the first time he replaced me.”

Johno Johnson, daily communicant, old-style Labor man, one-time President of the NSW Legislative Council, was an improbable friend. For decades they exchanged birthday greetings. One birthday, Gough was in Corinth. Whitlam’s ‘Letter to the Corinthians’ was the epistle received. Johno was forever saying: “It’s not too late mate. If you convert, you could be buried in hallowed ground. You’re a former Prime Minister. The crypt of St Mary’s Cathedral could be your final resting place.” “How much would it cost?”, Gough supposedly asked. To which Johno replied: “I don’t know. Ring the Archbishop’s secretary tomorrow. Here’s the number.” The next day a call came through, a priest explained to the Archbishop there was some guy on the phone wanting to know how much it would cost to be buried in the crypt. “Tell him $100,000” was the testy reply. The message conveyed; Gough supposedly exploded: “$100,000!!! I only need it for three days!”

Freudenberg, in his eulogy in 2014, said:

Gough was very serious about making us laugh. Not least at himself, and his ego. There was a lot of laughter in the Whitlam years. Some tears too. But always, energy, urgency, enthusiasm, for the high and noble calling of political service. Drive and purpose for his Party and his country.

Immersed in the majestic calling of politics, Whitlam changed his party and politics in Australia.

Whitlam’s voice, their sonorous, rich tones, silences, modulation, combined with telling expressions conveying irony, paradox, and policy exhortation were part of the appeal. Last weekend, Janan Ganesh in the Financial Times wrote an article: ‘We need to talk about voice privilege’. It is more than eloquence that explains some political successes. Ganesh says: “In almost any domain — corporate, electoral, romantic — those with good timbre and pitch are at a monstrous advantage. In meetings, I see perceptive mumblers lose out to sonorous mediocrities.” In this case, deep and textured, with bright and terrific phrases combined with substance, you can understand why people wanted to be around Gough.

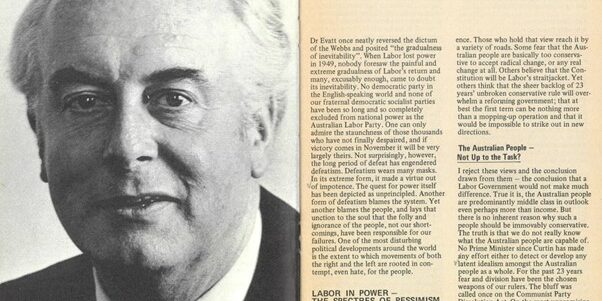

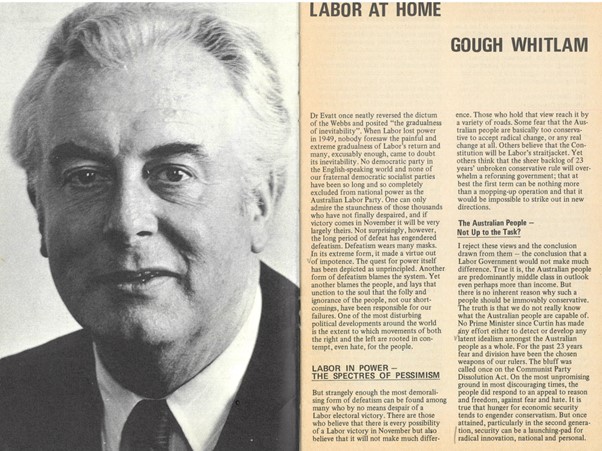

Whitlam strove to do great things. Obviously, the great mistakes temper the warm inner glow. In preparing for today, I found a Victorian Fabian Society pamphlet on Labor in Power by Whitlam and foreign policy writer and thinker Bruce Grant. The latter was appointed High Commissioner to India in 1973 (to 1975) and wrote prolifically on Australia’s relations with the diverse and multi-faceted nations of Asia. At first, I thought the pamphlet might discuss the government’s achievements part-way through its term. Instead, written in July 1972, it was projecting what difference Labor would make. Whitlam wrote: “No Prime Minister since Curtin has made any effort either to detect or develop any latent idealism among the Australian people as a whole.” Whitlam disputed the idea that the Australian people were unambitious for their country.

It is interesting, as many of the authors in the book do, to look beyond the immediate period of the government, to see longer term consequences. Duckett’s Medibank/Medicare chapter and Hort’s on education, are just two in the book that ask the question and assess what happened to the Whitlam reform agenda in particular fields. How often have you heard it said: “Thank God I live in Australia.” Universal health care developed by Whitlam and Bill Hayden is one such reason.

So much is covered in Prasser and Clune – in addressing that time of Labor in power, economic policy, constitutional change, DURD (Department of Urban and Regional Development), Rattigan and tariff reform, the social welfare reform legacy, Aboriginal reconciliation, the differences with, the implications for and continuity with subsequent administrations, and all the rest.

I wrote on the promise and performance of Whitlam’s foreign policy. As prime minister, Whitlam established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China; reached a settlement with the United States on vital joint defence facilities; revitalised the ANZUS alliance, in the context of a more robustly independent Australia; presided over the establishment of an independent Papua New Guinea; actively engaged with the rest of the world – forging relations with world leaders, like no one before him. It was a period of optimism, excitement, challenge. Some changes were immense and long lasting, others ephemeral.

I remember hearing the news in 1971, Whitlam now in Japan after the China visit that July, the Kissinger announcement that Nixon would be going to China. My brother Shane and I were home from school listening to Brian White on Radio 2GB. The China gamble had paid off. All McMahon could do was to say it was pathetic that Whitlam did not know Kissinger was in Beijing at the same time.

Bruce Grant, in that Fabian pamphlet, predicted that Labor in government would correct course on overdue changes of direction in Australian foreign policy, that would not be overruled subsequently. Recognition of China was the obvious example, another being the achievement of joint control of US defence facilities and reducing the secrecy associated with them. Grant referenced an outrageous speech of McMahon’s Foreign Minister, Nigel Bowen, in New York where he exhorted an American audience to be very concerned by the prospect of a Labor government. They were in office so long, the Liberals; they thought Australia’s interests were exactly synonymous with their own.

Sometimes, speaking personally, it was hard to stay objective. I followed Whitlam as a kid. In 1968, aged 13, I was up in front of 60 kids in my school class — “as crowded as a Catholic school” was one of Barry Humphries lines at that time — and with my brother we defended Gough. We were early dewey-eyed Whitlamites. Mary Easson, a fellow contributor, remembers her father in 1967 watching Gough on television and remarking to his daughter that Whitlam is the man to take us back.

Whitlam still evokes visceral reactions. Few names resonate so powerfully in Australian political lore. I doubt any other Australian government in Australia’s history, of three years’ duration, would have “Era” in the title of a book commemorating their period in office.

Someone I respect, after reading my chapter and the draft of a longer monograph on the same theme said: “It’s a labour of critical love, what you wrote, isn’t it?” Yes.

Hagiography is lazy writing. You show more respect painting the portrait warts and all. That is what I and other authors set out to achieve in writing about the man who did so much to challenge and change us. Read the book to appreciate the long roar of those times continue to reverberate still.

Postscript (2023)

I mostly spoke off the cuff; the above being notes I glanced at, sometimes not as extensively as I should have.

Bob Carr launched the book, with remarks from John Faulkner, Linda Hort, Scott Prasser, and me.