Article written 8 February 1995.

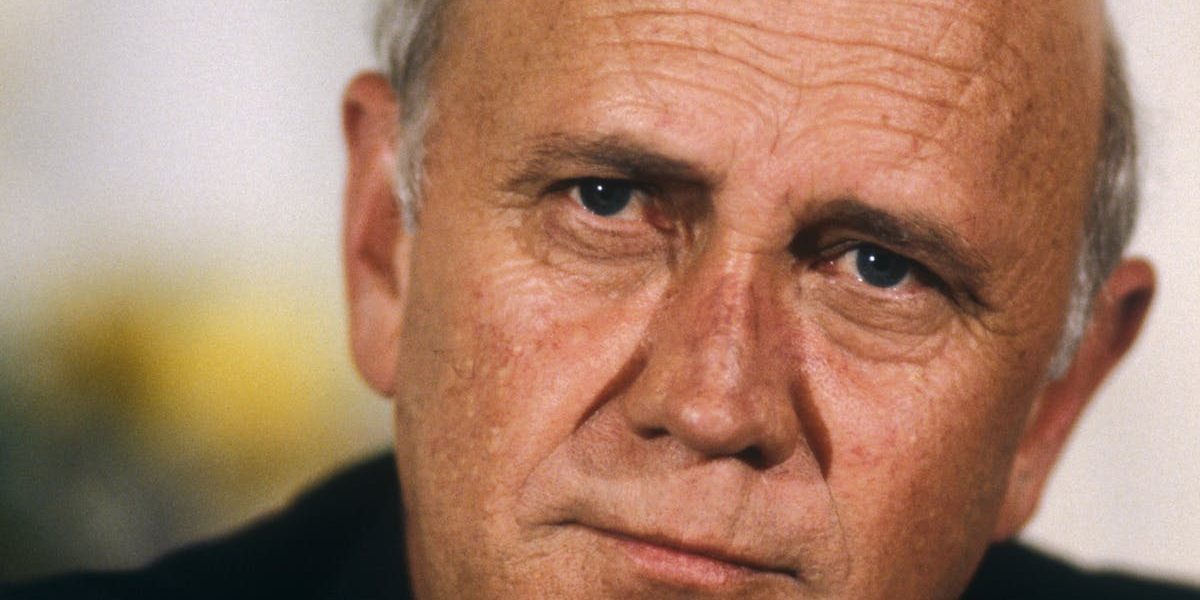

A few people might have felt cheated at the recent lunches in honour of the Second Deputy President of South Africa and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, F.W. de Klerk.

Here is a man – at the centre of exciting events – paying his first visit to Australia. There are plenty of interesting questions worth pondering: Why did Mandela publicly attack him in recent times over the amnesty granted to former police and security personnel in the dying days of de Klerk’s period as South African President? Why did de Klerk not explain his intentions to Mandela beforehand? What thoughts raced through his mind when he read Mandela’s recent biography – which was sweet and sour concerning Mandela’s attitudes to de Klerk’s integrity?

Nothing much was revealed about what de Klerk thought about these things. Almost embarrassingly so, the man sounded greyly boring.

This is the most reassuring thing about the de Klerk visit. The German novelist, Günter Grass, once observed that a sign of a truly mature, prosperous and healthy democracy is when its politicians are boring!

Mr de Klerk sounded like a Premier of South Australia with the usual noise about the gates are open, our system of education is one of the best in the world, investment opportunities are unlimited, etc. Instead of rhetoric about “come to South Australia, gateway to South East Asia” or “gateway to the Nullarbor desert” or whatever, it was friendly talk about South Africa as the gateway to surrounding economies of over a 100 million people.

Mr de Klerk also proposed an Indian Ocean economic zone which sounds a bit absurd, particularly when the idea is joined by allusions to Australia and South Africa being “neighbours”. The Indian Ocean is a big fence. What de Klerk wanted to emphasise is the point that South Africa is back in business. In contrast with APEC, where trade links across the Pacific are strong, the links across the Indian Ocean are (currently) fairly weak. In this sense it is much harder to talk about an Indian Ocean trading “region”. But the future may be different, especially as the Indian economy continues to mature and prosper and trading links between Australia, India, and east and southern Africa intensify.

As for the events in South Africa, Mr de Klerk highlighted his concerns about industrial relations and the need for future confidence in political stability. In doing so, he sounded like another conservative. But what he said was right. Industrial militancy – a reflection of years of frustration and repression followed by disappointment in the hard slog of building the South African economy – is a potentially crippling threat. The main challenge is to maintain social harmony in the context of rapid change.

That is why the debates over a new constitution and the post-coalition arrangements are so important. A sign of de Klerk’s wisdom is his understanding that to break up the existing coalition government of national unity would be to vastly lessen South Africa’s chances of becoming, within this decade, a stable beacon of economic prosperity and stability on the African continent.

In this, as in so many other things, President Mandela’s health, mental dexterity and character are so important. In 1990 the Labor Council of NSW organised a huge rally, ‘In Union with Mandela’, at the forecourt of the Sydney Opera House. I met him. I was sceptical of the popular, press portrait of Mandela as a serene, bitterless man of peace. I wondered whether he might show his true colours – whatever those might be. All I saw and heard was the only person I have ever met who seemed so obviously a good man. Everything in the hagiographical descriptions seemed the reality.

The task, however, of building the new South Africa remains immense and the possibilities look fragile. Despite the grounds for optimism, the economic situation in South Africa looks difficult; unemployment is around 40%; apartheid has left many legacies including a poorly trained black labour force. Poverty, including urban squalor and housing shortages, leaves many South Africans in a situation of angry desperation. South Africa needs all the saints, scholars, pragmatists and technicians it can find. For a while to come, South African politics will be anything but boring.

Postscript (2015)

This was submitted to the Australian Financial Review but not published. I did not want to commit to a weekly or fortnightly column. As a free-lancer, you take the risk of your piece being discarded due to something more interesting or contemporary appealing to the Opinion page editor, on the day.

As for South Africa, the continuing economic, social, and educational advancement of the country over the past twenty years, despite dysfunctional politics, post-Mandela, is striking.

The decline in the political and law-and-order situation, however, since this piece was written of the African National Congress (ANC), once a competent, well-led force, is surely one of the most worrying developments in modern day South Africa.

It appears at this moment that the country could go either way. A new courage and moral leadership is called for.