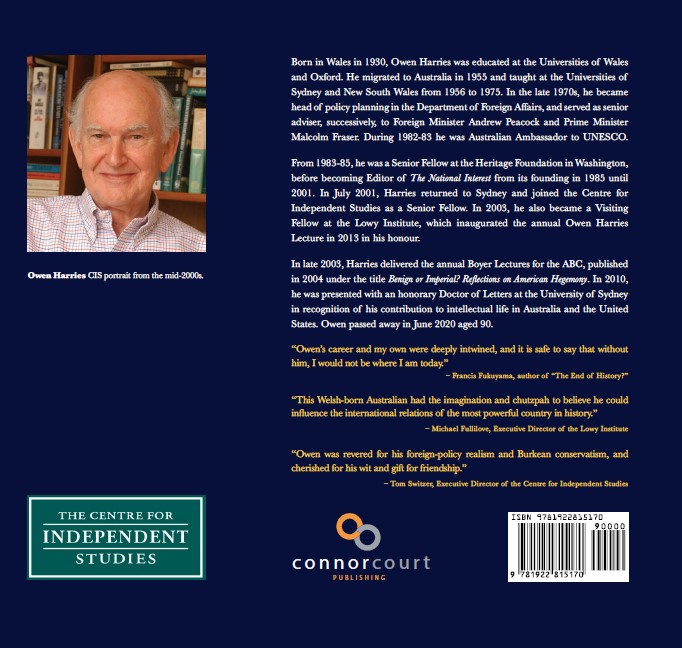

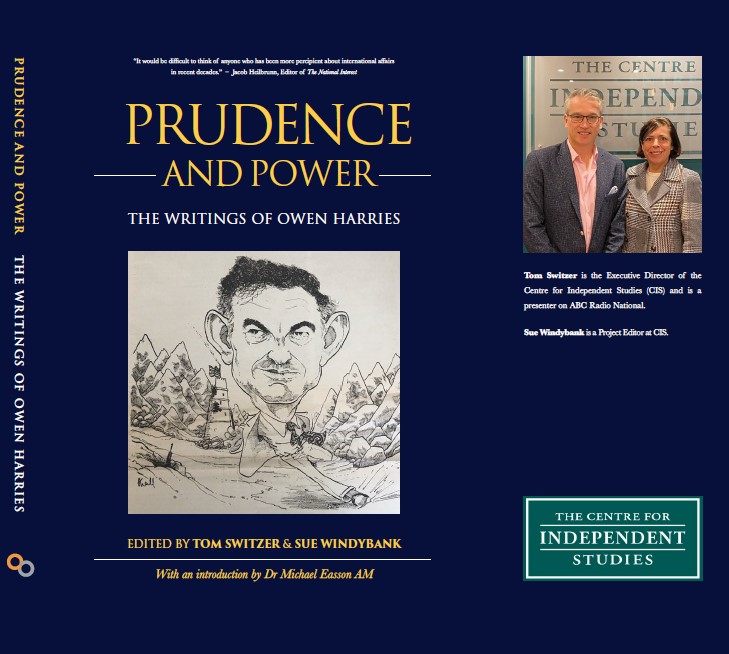

Published in Tom Switzer, and Owen Harries, editors, Prudence and Power. The Writings of Owen Harries, The Centre for Independent Studies/Connor Court Publishing, Redland Bay, 2022, pp. v-x.

All of us knew Owen Harries, the three instigators of this book, Tom Switzer, Sue Windybank, and me. We admired his thinking, his ideas, the craft he applied to wordsmithing, the jesting and jostling in debate, the integrity he displayed respecting others’ viewpoints, the originality he brought to important questions.

He was not a ‘quietly flows the don’ intellectual. Owen aimed to pierce armour. He was engaged in making his interlocutors consider, reassess, and calibrate their viewpoints, imagine different conclusions; to evaluate whether their shields were bullet-proof, whether the familiar carapace covering their ideas gave much protection.

Owen, his pipe a distinctive memory, taught me ‘Australian Foreign Policy’ and ‘International Relations’ at the University of New South Wales in 1975. I stayed in touch thereafter. In the early 2000s at Café Sydney, Owen introduced me to Tom Switzer. Before Tom sat at our table, Owen said: “He is an enterprising fellow who has discovered most things I’ve written including a few best forgotten.” Tom got to know Owen by reading the Washington-based National Interest magazine that Owen co-founded and edited from 1985-2001, and in the late 1990s they bonded over a mutual dislike of American over-reach in the aftermath of the Cold War. Tom’s enthusiasm, and his role at the American Enterprise Institute (1995-98) in Washington led to a strong friendship, further strengthened after Owen and his wife Dorothy returned to Australia in retirement in 2001. Owen became a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) in Sydney, and Tom and Owen sometimes collaborated in writing. Sue Windybank, as CIS publications editor, got to know Owen, published some of his articles, and conducted a memorable interview which distilled Owen’s thinking.

When Owen died in 2020, we knew what we had to do – assist each other, especially Tom, in gathering his best articles for a book, develop a definitive bibliography, and decide how to best convey the importance of this man to those who knew his writings, and the wider universe of people who should. Hence this book.

We knew Owen had come a long way, intellectually. Born near the slag heaps of South Wales, he had not met a single conservative until he arrived at university. A man of conventional, Fabian-inspired leftish opinion, Australia changed him. A poster in the UK promoting migration to Australia, an advertisement for a Tutor’s role at the Department of Adult Education at the University of Sydney led to curiosity, application, success, and arrival in Sydney with Dorothy in 1955. What he saw “was immediately and gloriously attractive, a marvellous technicolour relief after a grey post-war decade: flawless blue skies, palm and flame trees, yellow beaches, and, not least, plenty of red meat and fruit.” But he knew no-one.

An early formidable intellect was the John Anderson-inspired Harry Eddy (1913-1973), also in the Department. Harries recalled: “I can remember arguing with him during my first years in Sydney, and always having a sense of impending defeat.” He went on to say that Eddy “took great pains to meet his opponent’s case at its strongest and was never concerned simply with winning. Indeed, it was the combination of power and fairness which stayed in the mind as an object lesson of what academic work could and should be.” Eddy was the example Owen aspired to and surpassed. Owen edited a festschrift in honour of Eddy, Liberty and Politics. Studies in Social Theory, 1976, and encouraged the publication of W.H.C. Eddy, Understanding Marxism, Edward Arnold, 1979.

Harries learnt to debate, inspire, and win with the best. He gravitated to the circle around Quadrant magazine and its founder Richard Krygier (1917-86): The magazine “…became a rallying point for Australian intellectuals who rejected the prevailing leftism and the perverse but comfortable notion that principled liberalism required an anti-anti-communist posture.”

Peter Edwards and Greg Pemberton, in their history of Australia’s Vietnam engagement (Crises & Commitments: The Politics and Diplomacy of Australia’s Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948-1965, Sydney, 1992) tribute Harries along with Geoffrey Fairbairn (1924-80) at the ANU, as the leading intellectuals in Australia publicly articulating the defence of Australia’s participation in the war in support of the independence of South Vietnam. Their arguments were more compelling and interesting than what the government ministers and spokespersons said. Owen was never just a tough Cold War warrior. Wit and iconoclastic insight were part of his inventiveness. It is why even serious ideological opponents often liked him personally. You knew he cared very much to win, but even more so to win you over, and he had a knack of listening like you might have something interesting to say.

****

One regret is not seeing in this book more of Owen’s writings. There was so much, however, from which to choose. For example, his articles in the early 1960s in the globally prestigious Foreign Affairs journal on “Faith in the Summit” and “Six Ways of Confusing Issues”, written when he was 30 and 31. Apart from Julius Stone (1907-85) who proposed in 1959 a “hot-line”, a dedicated telephone connection between the White House and the Kremlin (implemented in 1963), in that period, besides the Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, there was no other Australian figure having as significant, considered, and practical policy impact on the world stage. Needing to select from a vast output (as the bibliography at the end of this book shows) and knowing many of his earlier themes were revisited and sometimes repeated, led the editors to concentrate on more recent articles. That bias is justified. Owen’s writings improved as he matured and refined his thinking.

Owen worried that he had never developed an overarching theory of international relations. But this was not his forte. Besides, there is merit in the argument by the realist policy thinker Martin Wight (1913-72), who in the journal International Relations wrote on “Why There is No International Theory” (1960). Wight and Harries were sceptical of grand explanations. Discussing issues as important as the organisation of relations between nations requires nuance and a lively appreciation that neat and tidy first principles can be blind to reality of history, individuals, and differing conceptions of national interest. In his sparkling essays, “The Dangers of Expansive Realism”, “Fourteen Points for Realists”, and others reproduced in this collection, Harries brought his scalpel to the table.

He urged caution, prudence, restraint, awareness of the fallibility and unpredictability of human beings, the ever-present risk of unintended consequences, to consideration of what can be accomplished. He wrote: “Resist the notion that we must now find a new, grand, elevating cause to perform the same function as anti-communism did until recently – that of providing coherence, unity, and high moral content to foreign policy. The Cold War was exceptional, not typical.” Owen shifted his thinking as circumstances changed.

He contested the “sleep-walking” opinion that America should act as if the Cold War had never ended, cautioned that the United States’ need for enemies and high purpose might lead to major strategic mistakes. With the ever-eastward expansion of NATO, he foresaw potential catastrophe. The Iraq adventure, also, its poor strategic objectives, and the extraordinarily utopian prognosis of “democracy-creation,” blithely tossed around during the George W. Bush presidency, was a project bound to end in tears. Owen was alive to risks, his warnings unheeded. In one essay, “Realism in a New Era” (1995), reprinted in the pages ahead, he opined: “Realism is an affront to liberalism in many ways… It stresses conflict as a central and enduring fact of life, while liberalism asserts a true and peaceful harmony of interests, obscured only by temporary and removable ignorance and misunderstanding.”

With Iraq, Owen saw the difference between liberals and neo-conservatives (whom he thought were “neo-liberals” on foreign policy) as opposed to conservative realists was scepticism about the perfectibility of mankind. Alas, there is no white cocoon, silky chrysalis remedy. Never is it easy or quickly possible to transform whole societies, especially where tribal hatreds, long memories, and the honour of blood-vengeance are important, into sustainable, “end of history,” liberal nations. The pre-mature promise and the hasty actuality of majority rule in such cultures is certain to bring boiling feuds to the surface. This is not to advocate cynicism or indifference. Nobility of purpose, yes; but policy-makers need always reckon with “the crooked timber of humanity,” in Kant’s phrase. It is not one or the other.

Turning his gaze to Australian policy, Owen urged that Australia need not share every burden and every engagement in lockstep with America. We had our own thinking to do and interests to protect. Yet he also insisted that the American alliance was the cornerstone to Australian policy, though nothing should be taken for granted. In correspondence published in the Quarterly Essay, No. 25, 2007, Harries observed:

As statesmen as diverse as Bismark, Gladstone and Teddy Roosevelt had cause to stress, the reserve rebus sic stantibus – “while the same conditions apply” – is always silently understood in every treaty. In other words, no firm and unconditional guarantees are ever available in international politics.

And, therefore, every important relationship, in particular Treaty relationships, need to be permanently cultivated and renewed. His Boyer Lectures (2003) convey the point and punch of his reasoning; the best of those lectures is reproduced here. Owen, discussing “The False Choice Between Realism and Morality” in The Interpreter, the Lowy Institute’s online publication, in February 2009, proffered:

I suggest that instead of classifying people as either wholly realist or wholly moral, it might be better to acknowledge that both elements exist in most if not all of us, the nature of the mix depending partly on temperament, but also on experience and understanding of the facts of a particular situation, and of the nature of the international system in general.

He went on to say:

In so far as realism stresses the importance of stability and order, it stands for the necessary (but far from sufficient) condition for a moral life; and in so far as it emphasises selfishness, secrecy, and mutual suspicion, it forewarns against unintended consequences (The road to hell is paved etc., etc…).

How best to grapple with the challenges of the times he lived, how to apply principle and realism to reach coherent outcomes, how best to attain plausible and compelling conclusions, discarding cant and woolly thinking, made Owen a fine writer on foreign policy.

More the applied strategist than a grand strategic theorist, what we have here is a rich harvest of writings by Owen written over a half century. A crop of the best lay before you. Read them and see how the art of substance married to fine rhetoric, spotlights issues, values, and pathways guided by a hardy realist outlook.

Congratulations Tom and Sue, you have done great honour to our wonderful, mutual friend.