Slightly edited extract from Michael Easson’s monograph, Whitlam’s Foreign Policy, Connor Court, 2023, published in The Tocsin, journal of the John Curtin Research Centre, No. 18, May 2023.

Nine days before Kissinger’s visit, nine months before Nixon’s, Australian Opposition Leader Whitlam visited China in July 1971. On no diplomatic issue has the McMahon government suffered more embarrassment than that of relations with China. On 12 July 1971 Liberal Prime Minister McMahon boasted: “In no time at all Zhou Enlai had Mr Whitlam on a hook and he played him as a fisherman plays a trout.” McMahon “was left uninformed” of Nixon’s strategy, announced with Kissinger’s trip to Beijing 9-11 July 1971, to open diplomatic channels to China. Within weeks, the Americans announced a China strategy that made Australian conservatives look awkward and locked into an out-of-date policy paradigm. Margaret Whitlam remembered: “Gough could not stop himself from laughing at [McMahon’s] gaffe. Neither could the media.” Recognition of the Peoples Republic of China was conferred by newly elected Prime Minister Whitlam on 22 December 1972.

Australia “acknowledged” China’s claim to Taiwan. In contrast, in October 1970 the Canadians “took note” of the claim. Would it have been wiser to “note” rather than “acknowledge” China’s claim to Taiwan? Stephen Fitzgerald, Australia’s first Ambassador to the Peoples’ Republic, who had learnt Chinese in Taiwan in 1964 understood that in the previous three hundred years “the island was only nominally ruled by the Chinese government”. The Chinese pressed for stronger wording than what they got from the Canadians a few years before.

Both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China on Taiwan had campaigned for full recognition of their claim to be the legitimate government of all of China. The word “acknowledge” is stronger than “note” as the former can mean “accept the validity or legitimacy of” (Oxford English Dictionary). The Americans too, on 27 February 1972, in the Joint Communiqué of the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China, also known as the Shanghai Communiqué, formally acknowledged that “all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China.” This document was signed by Nixon during his visit to Beijing in February 1972. Beforehand, Mao promised no military conquest, saying: “The small issue is Taiwan; the big issue is the world.”

Taiwan was yet to develop into a thriving democracy. In 1972 General Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) ruled the island under martial law. But that was not the end of Australian considerations. Perceptively, on future Australian-Taiwanese relations, in a 1 April 1973 memo to Australian Ambassador Fitzgerald, Whitlam wrote:

Present Chinese thinking appears to be against armed action and in favour of liberation by ‘people’s diplomacy’. We hope that this policy will continue and be successful. In the meantime, we intend to be quite firm in insisting that private trade and travel between Australia and Taiwan should continue. To use Peking’s own argument, we have nothing against the people of Taiwan.

Fitzgerald himself confidently proclaimed: “[Australia] is able to contemplate a rational relationship with China, independent, and free from the neuroses of the Cold War.” More realistically, as Whitlam’s biographer and speechwriter Graham Freudenberg wrote: “Whitlam’s China initiative involved a felicitous combination of timing, courage and luck.” Fitzgerald recognised it was luck that made the visit appear prescient or well-judged – Whitlam visiting in 1971, just before Kissinger: “But the ALP move was grounded on a policy which had been debated and endorsed by the party…”

In 1971, during Whitlam’s first visit, China was still a strange place. Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997) remained banished to the countryside as a worker at the Xinjian County Tractor Factory in rural Jiangxi province. The disastrous Chinese Cultural Revolution was unsubdued. Reform prospects looked unpromising. In 1972, however, Deng’s apology to Mao led to the possibility of a return from exile to Beijing. In 1973, Premier Zhou Enlai (1898-1976) brought Deng back to Zhongnanhai, the central government compound, to focus on reconstructing the Chinese economy.

Whitlam, based on his meeting with Mao in early November 1973, recollected that: “[Mao] lacked Zhou’s grasp of detail and incomparable knowledge of particular events and personalities, but his wisdom and sense of history were deep and unmistakeable.” It was wise for Australia along with other nations in the 1970s, the United States particularly, to belatedly cultivate healthy diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. But given Mao’s murderous legacy, his “wisdom” is an odd thing to note in celebratory terms.

On Whitlam’s second trip to Beijing, as prime minister, in late October/early November 1973, he proposed to Zhou Enlai: “There should be consultations between Australia and China as close and significant as we have traditionally had with Britain and the United States and similar to discussions we now have annually with Japan at ministerial level and with the Soviet Union at the officials’ level.” In writing that, Australian Ambassador Fitzgerald noted that the then head of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs, Sir Keith Waller (1914-1992), looked at the ceiling as Whitlam said those words. Whitlam’s statement expressed the beginnings of Australia’s desire to know China well, to act as a bridge in explaining China to allies, and to forge a creative relationship, without being either uncritical, doting, or hostile. That remains Australia’s ambition today.

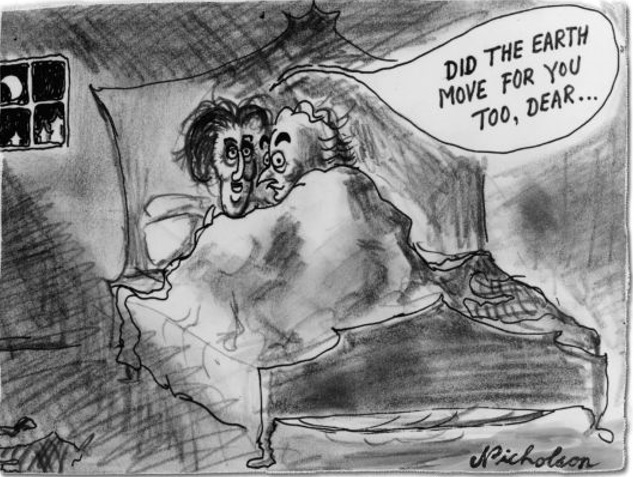

As a side note, on a subsequent visit to China, Gough and Margaret Whitlam were in Tientsin, an hour’s drive from Beijing, on 28 July 1976 when a severe earthquake hit at night. Peter Nicholson composed a cartoon, decried by some as in poor taste:

Whitlam purchased the original, framed it, and hung it over the marital bed. As Peter Hartcher, the Sydney Morning Herald journalist wrote in 2014: “The Whitlams had a sense of humour. And Gough was entirely at home with great tectonic shifts.”

Perhaps it is an ironic tribute to Whitlam’s success that the opening of diplomatic ties in 1972 is now seen as necessary and relatively uncontroversial. Whitlam’s move in 1971 to visit China and forge diplomatic links, was innovative and courageous. This was in defiance of conservative allegations that Whitlam was soft on communism, a witless tool of Mao, and conducting – in Prime Minister McMahon’s phrase – “instant coffee” diplomacy. It is not unfair to say that Coalition governments in the early 1970s were lazy and confused or, more charitably, unable to guide a small power at sea in a storm.

Of one thing there can be no doubt. Whitlam’s realism about recognition was consistent throughout his political life. As he said in the debate on international affairs in the parliament on 12 August 1954:

We must recognise the fact that the government installed in Formosa [the name for Taiwan coined by the Portuguese] has no chance of ever again becoming the government of China unless it is enabled to do so as a result of a third world war. When we say that that government should be the government of China, we not only take an unrealistic view but a menacing one. The Australian Government should have recognised the Communist Government in China, in view of the fact that all our neighbours, including the colonial powers, Great Britain and the Netherlands, have recognised it.

Labor policy, from 1955, had been to recognise the PRC. On this score alone – initiative, boldness, and long-term impact – the visit to China in 1971 and return as prime minister in 1973 marked Whitlam’s importance as one of the greatest of Australia’s foreign ministers.