Interview between Tom Switzer and Michael Easson broadcast on Friday 9 June 2023 on the ‘Between the Lines’ program on ABC Radio National.

Tom: I’m Tom Switzer and this is Between the Lines.

Also, coming up, Gough Whitlam’s foreign policy.

“It is that Australia, under my government, intends to be a mature, responsible, and generous member of the international trading community. Yet, at the same time, an Australia determined to be master of her own household. I hope it will never again be said in this forum by any Australian minister from any Australian political party that (inaudible) are small and insignificant countries.”

That was Gough Whitlam as prime minister about 50 years ago. Stay with us for a review of Whitlam’s foreign policy.

…

You’re listening to Between the Lines here on RN.

Tom: Well, Anthony Albanese, he’s certainly been busy overseas lately, hasn’t he? From his trips to London for the king’s coronation, Tokyo for the G7 to Singapore and Vietnam in the past week and within the month, he’s off to of all places Lithuania for the NATO Summit.

Now, Australia’s penchant for diplomatic busyness and participation, it predates this PM. During World War I, the patriotic song went “Australia We’ll Be There” with ‘there’ meaning the war’s obscure battlefields. Ever since, being there apparently means every global committee, conference, commission, voting lobby and site, and not simply registering in a photo-op but participating as prominently as possible.

Now, one political figure who best reflects this tradition was Gough Whitlam. Throughout his three-year prime ministership, so from late 1972 to late 1975, he set new records of pace and endurance. During much of his first year in power, Whitlam was also, believe it or not, foreign minister. Add to this Whitlam’s extremely dominating personality combined with a formidable will and impressive intellect. There’s no question that in foreign policy, as my next guest says, no previous prime minister exercised such untrammeled power. So, nearly half a century later, what’s the verdict on Whitlam’s foreign policy.

Michael Eason is author of Whitlam’s Foreign Policy. It’s just published by Connor Court. Defense minister Richard Marles recently launched the book in Sydney.

Michael, welcome back to the program.

Michael: Thank you very much, Tom.

Tom: Now, let’s start by putting Whitlam in a broader historical context. Take us back to 1972 just how did he distinguish Labor foreign policy from the coalition, which of course had been in power since Menzies’ election in 1949.

Michael: It sounds a cliché, but Whitlam portrayed the Liberal Country party coalition as tired and unimaginative. I think they were, and that was illustrated by Nigel Bowen, the then foreign minister in New York, speaking at the Asia Society [around early 1972], warning his audience about what a Whitlam Labor government could do to jeopardise Australian-American relations. They were so arrogant that they would criticize a future government at an international forum, warning of dangers to Australia, at the Asia Society. I think they were tired, unimaginative and this very much showed with some of the initiatives that Whitlam took in opposition as well as in government, for example our position vis-a-vis China.

Tom: Yeah, tell us about that because, I mean, that was a big risk by Whitlam, wasn’t it, in 1971 as opposition leader?

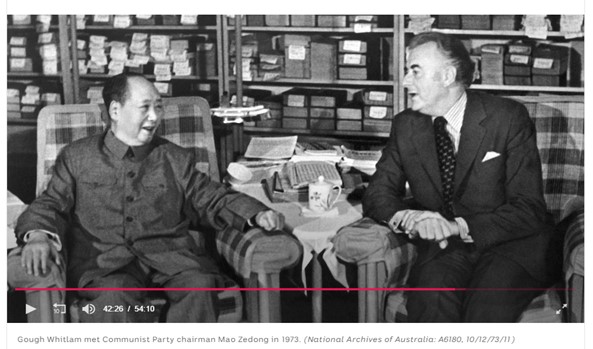

Michael: Yes, it was. And Whitlam, actually in 1954 was the first federal MP who advocated Australia should recognise the Peoples Republic of China.

Tom: 1954?

Michael: 1954. Labor Party policy changed in 1955 to recognise [the Peoples’ Republic of] China but what happened in ’54 was that Clement Attlee, the former British Labour prime minister, visited Australia. He was then leader of the opposition [in the UK]. And he advocated privately with [Australian] Labor MPs, “You should follow the British example which is recognise the government that controls the territory. Don’t adopt the American policy where diplomatic relations was often conferred to countries you like or where it was a negotiating ploy.” The British approach, I much admire, recognised the country’s government [if it was in control of its territory] and that should determine diplomatic relations.

Tom: And then so, in July 1971, when Whitlam goes there, and this was just before Henry Kissinger who was President Nixon’s National Security advisor, this was just before Kissinger’s secret visit. I suppose, from Whitlam’s perspective, this was long overdue.

Michael: It was. He decided to seek an invitation to China, and he asked his advisors, one of whom, Graham Freudenberg, Whitlam’s biographer and speech writer, and great friend, Freudenberg said “Don’t do it. It could be very controversial. You’re going to win the election due in ’72 anyway. Why take the risk?” But Whitlam decided to send off a telex to China to seek an invitation. And he visited in 1971. The then [Australian] government, the prime minister Billy McMahon, said that Whitlam was being played like a trout by Chou En Lai, the prime minister of China, and he denounced Whitlam for being foolish in going to China and pandering to the Chinese communists.

Tom: Instant coffee diplomacy, I think, he said, Michael.

Michael: Yes, he did. And I remember being at school at this time. I wondered how all of this would go with the public. And then Whitlam was in Tokyo after he left Beijing. And the news came out that Henry Kissinger was in China in 1971 negotiating for the US president to visit the next year. I thought Whitlam was ahead of his time. And that, I think, was both a very positive aspect of Whitlam’s imagination, drive, bravery, but it also had consequences for him as he believed he could do anything. He overruled his advisors, he was the great statesman in foreign policy. Like you pointed out in your introduction, Whitlam was both foreign minister and prime minister for his first year in office and effectively dominated foreign policy for the whole time he was there [as PM].

Tom: Yeah. And in 1973, this is Whitlam’s first year, he does go to Washington to meet with President Nixon and the national security advisor Kissinger. Now, obviously, Whitlam, Nixon, and Kissinger agree on the whole point of re-normalising relations with communist China but Nixon and Kissinger were very skeptical of Whitlam and his world view. How so?

Michael: I think they had two views about Whitlam. One was that they thought him as a naive idealist clinging to ideas of human rights and that sort of approach to foreign policy. And they were also critical of Whitlam and his ministers for their criticism of the American bombing of North Vietnam of Haiphong and Hanoi in December of 1972 and January 1973. Certainly, there were many intemperate remarks by Senator Gietzelt and other prominent personalities, Jim Cairns in the Whitlam government, about all of that. And Whitlam wrote a letter, criticising the American strategy, to the US president and Nixon declared “I’m not meeting this man or any other minister in the Whitlam government.” That would be the key message he announced to his cabinet and to his colleagues. To the great credit of Andrew Peacock, who was shadow minister of foreign affairs immediately after 1972, he visited Washington and persuaded George Bush – who later became vice-president and president –that that would be a bad policy. And Bush [who was then Chair of the National Republican Committee] introduced him to Spiro Agnew, the then vice president, and he conveyed the view to the president, which was Andrew Peacock’s view, that it would be damaging for Australian-American relations if the US president declined to meet Whitlam when he visited the US. So, that happened in 1973.

And Nixon got on well with Whitlam. In fact, Nixon made the comment in their interview that he’d never met an Australian he didn’t like in his life. Clearly, hed not met Jim Cairns at that time. They never did.

Tom: Jim Cairns and who else was it? Clyde Cameron, Tom Uren. They called Nixon and Kissinger fascists and mass murderers for the Christmas bombing of Hanoi.

Michael: Exactly. So, you can understand that the Americans wondered what the hell was happening with this new Australian government. But relevant to today, I think Whitlam’s two greatest achievements in foreign policy were recognition of China and, associated with that, forging better relations with many of the countries of Asia. Whitlam wrote a very interesting pamphlet Beyond Vietnam during the Vietnam war. In other words, [he suggested] we’re too obsessed with Vietnam, security, war associated with the United States.

Tom: What year was that, Michael?

Michael: I think it was 1968 or so, when that pamphlet came out. It was interesting, Whitlam was thinking beyond Vietnam. So, he was forward thinking. The other great thing that Whitlam did and was, I think, one of his greatest achievements in government was normalising the relationship between the United States and Australia on what used to be called the US bases, which consequently were known as the joint facilities. Whitlam renegotiated these treaties, some of which had enabled America to effectively run all operations unhindered, without Australia knowing what was happening, on Australian soil. He insisted they needed to be joint facilities, jointly run with Australian senior military personnel involved, in the running of the facilities. And that became very important for winning a consensus within Australia for redefining the relationship with the United States in the Labor Party. All of this is relevant to AUKUS [today] and everything else we see today. Without those initiatives, we wouldn’t have the solid foundations that enable Australia to operate independently, creatively, collaboratively in coalition but knowing that we’re not simply someone else’s patsy, we’re running our own policy and we have our own mind as to how that policy should unfold.

Tom: My guest is Michael Easson. He is author of Whitlam’s Foreign Policy and we’ve just been talking about Whitlam’s relations with the Americans during Whitlam’s prime ministership.

Michael, you mentioned in your book that Whitlam met with Lyndon Johnson in 1966. Let me put you on the spot here.

Michael: I think it might have been ’67.

Tom: Name the two other federal opposition leaders to meet a president in the Oval Office. They’ve been three in the history of our country. Who were the other two?

Michael: You’ve got me stumped there. I would imagine it would have been Malcolm Fraser but I’m not sure. And it could have been Howard.

Tom: As opposition leaders were talking about. I tell you what? You think about it and our listeners can think about it and I’ll mention it right at the end of this segment.

Now, moving on to Asia, Michael, you mentioned Whitlam’s interest in East Asia beyond Vietnam, Indonesia. Now, the Australian left has all too often criticised Whitlam for appeasing Suharto in the lead up to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor. This was in late 1975. Is the criticism justified?

Michael: I don’t believe so. I think we needed to forge closer relation with Indonesia. To Whitlam’s credit, he visited Indonesia frequently in opposition and in government. And forging the best possible relationship with the leadership of Indonesia was in Australia’s [national] interests. Where Whitlam had a distinctive view on Indonesia was when Indonesia decided to annex West Papua or Irian Jaya off the Dutch. Whitlam supported Indonesia effectively taking over all of the old Dutch West Indies, whereas the leader of the opposition at the time, Arthur Calwell, disagreed with that. Whitman thought that that view [of Calwell] was unnecessarily antagonistic to Indonesia and unrealistic that the Dutch could continue to run their colony in West Papua or Irian Jaya.

Secondly, the invasion of East Timor occurred after Whitlam was dismissed and during the period that there was a caretaker administration under Malcolm Fraser. What I think Whitlam did was to take the view that East Timor was an unviable state. I think the Portuguese was second to the Belgians in being terrible colonial masters. They left nothing behind other than the weapons of the governor in Dili left behind in East Timor when he fled the country in 1975. Fretilin, the Marxist radical guerrilla group, took those weapons. And Indonesia worried. Vietnam had fallen. South Vietnam had fallen in 1975. There were lingering memories of decade earlier, of the year of living dangerously, when the communists in Indonesia tried a coup in Indonesia. And there was fear that of radical Marxist communist East Timor could emerge as similar sort of governments as did [the governments] in Angola and Mozambique when the Portuguese left those colonies in Africa. Cuban guerrillas were suddenly fighting to support the governments that came to power in those countries. So, I think Whitlam took the view that we needed to realise that East Timor was unviable. And this is an example of the clash between a realist’s and an idealist’s policy perspectives. Whitlam is now seen as on the wrong side of history on East Timor. Largely it became a disaster both for the Australian legacy and for Indonesia’s due to the cruelty and the mass slaughter of innocents that occurred by Indonesian militia, by the armed forces when the invasion occurred, and that aroused mass sympathy within Australia for East Timor. Note they lost a lot of people during World War II. I think about 60,000 Timorese were killed by the Japanese in World War II. So, there was a resurgence of sympathy and respect for East Timorese independence but it’s an example of the tension between a realist’s and an idealist’s policy. And much of the outcome of East Timor turned on what the Indonesians did poorly in trying to incorporate that country into theirs. And hence, the subsequent history of East Timor.

Tom: Yeah. I mean, you generally paint a positive picture here of Whitlam’s relations with East Asia but not everyone agreed. Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of Singapore, who was prime minister until the early 1990s, he found Whitlam quick-witted but also quick tempered and he was glad to see the end of him. “It was a relief when the governor general removed Whitlam,” Lee Kuan Yew says in his memoirs. And he was particularly critical of Whitlam for his reluctance to take many of the Vietnamese boat people, Michael Easson.

Michael: The irony is that Lee Kuan Yew was quick quitted, quick tempered and acerbic as a personality. And he was also a great man and I deeply respect the achievement of Singapore. And I think he fairly made a criticism of Whitlam for being unsympathetic to the Vietnamese refugees that flowed out of south Vietnam after the conquest in 1975. But also ironically [worth mentioning], Singapore took hardly any refugees, so much of what Lee Kuan Yew’s –

Tom: I think Lee Kuan Yew’s point was that Whitlam made a big deal about ending white Australia policy and here was his great test and yet he called the Vietnamese effing yellow Balts, in private at least.

Michael: Well, that’s an interesting quote. I think that there’s no doubt that Whitlam was unsympathetic to the Vietnamese refugees and that is the blight on his legacy. We should have been embracing of those people fleeing persecution at that time and we didn’t under Whitlam’s leadership. The quote that’s often attributed to Whitlam came from Clyde Cameron in one of his [published] diaries but his diary entry is about Whitlam, what he said 18 months before. Whitlam subsequently denied that he said that, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the quote is accurate.

Tom: Okay, Michael, finally an answer to my political quiz question and those tuning in, I hope you’ve been thinking about this. Name the three federal opposition leaders who met the US president in the Oval Office. Now, Michael, you’ve mentioned Gough Whitlam with LBJ. That was in 1966. Who are the other two?

Michael: I’m imagining perhaps Menzies and Malcolm Fraser but I don’t know.

Tom: Look, it’s amazing. You are one of the smartest guys I know on American politics and history, and I’d suspect most people don’t know the answer but there are two others. Arthur Calwell, when he was Labor opposition leader, he met with John F. Kennedy in 1963.

Michael: Of course.

Tom: And the other one, believe it or not I was just talking to him this week and he told me, John Hewson. He met with President Bush and Secretary of State Jim Baker in the Oval Office in 1992.

Michael: Well, I’m glad to know that mate. I’ll never make that mistake again.

Tom: Michael, an absolute pleasure having you back to reflect on Gough Whitlam’s foreign policy.

Michael: Wonderful to talk to you, Tom. All the best.

Tom: Michael Easson. He’s author of Whitlam’s Foreign Policy. It’s published by Connor Court.