Article written 5 June 1995, but not published.

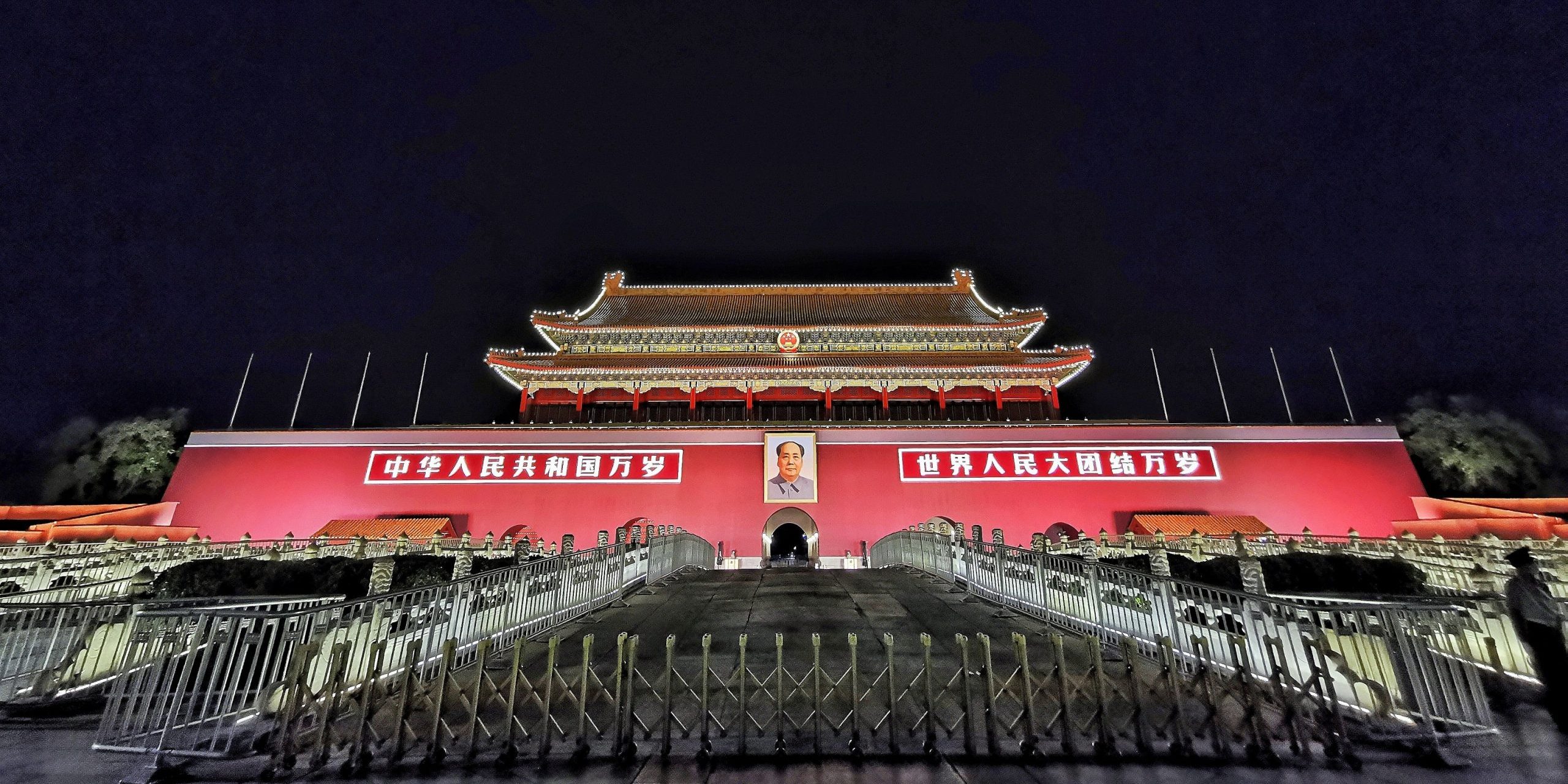

This week marks another anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacres in 1989. In Australia there will be fewer mourners and protests. In China any organised, public protest will be illegal and suppressed. At its most daring, there will be a few dropping of bottles by students outside of their cloisters. (Mr Deng’s name sounds in mandarin like “little bottle”. Smashing little bottles is a symbol of protest). Each year numbs the sense of indignation which occurred at the moment of the crushing of the Chinese student protests. Why?

Time moves on. The reform process in China continues apace. The juvenile protests of the time seem naive. Many student leaders paraded around the West, sounded, looked and acted immaturely. Too many sounded as coherent as Bob Dylan at his worst and thought they were China’s Vaclav Havel. Maybe the Chinese authorities had half a point about reckless adventurers.

Such a view is flawed. But impressions and re-assessments – widely believed – have undermined the Chinese students’ original appeal.

This is certainly true in Australia. Six years ago there were huge protests. The Prime Minister broke down and wept about the events. Now few seem interested.

At the time I coordinated union bans on the Chinese Consulate in Sydney. (Contrary to the recent ANU booklet Australia’s Reaction to the Beijing Massacres, those union bans did not collapse). For three months the Municipal Employees Union refused to take away the Consulate’s garbage. Consulate employees had to remove their own rubbish.

Was this an abuse of union power? It seemed like a good idea at the time. It provoked outrage. One call came from the ACTU conveying the concerns of the Department of Foreign Affairs that the Chinese might reciprocate with Australia’s embassy in Beijing. What to do?

I rang Michael Duffy who was then the Acting Minister for Foreign Affairs. He was supremely skeptical of the advice from Foreign Affairs. “These people are so precious and unworldly. They tried to draw a distinction, in a terrorism paper I saw, between terrorism and the activities of the PLO. So I asked ‘what was the difference between them and the IRA?’ They couldn’t give me a sensible answer.” Duffy suggested I check with the Prime Minister.

So I did. I tracked down Mr Hawke to a television studio in Ballarat. “This better be good mate”, he said to remind me of the inconvenience he was putting himself through in taking the call.

I praised his reaction to events and gently raised the concerns of Foreign Affairs. “Do you really have any worries with what we’re doing?” He did not. The bans remained. No one from government subsequently approached me about the idea of lifting the bans.

Around the country huge demonstrations occurred. Most, over 90%, were Chinese nationals. Some were genuinely frightened. Some saw this as a golden opportunity to gain residency in Australia. Quite a few published small advertisements in the Chinese-Australian press to denounce the regime. This would later serve as ‘evidence’ that the individual concerned would be in danger if forced ‘home’. So a mixture of fear, opportunism and great expectations influenced the decision of thousands to stay in Australia. Such behaviour is hardly reprehensible.

Australia eventually accepted over 20,000 Chinese students – most of whom were studying English; in contrast, those who stayed behind in the USA were of higher academic standing or studying at university, many at post-graduate level.

Australia did the right thing. In the aftermath of June 1989, the Labor Council of NSW advocated permanent residency for all the students who remained behind, subject to the usual checks. Australia’s openness to the plight of these people reflects Australians’ tolerance and humanitarian instincts. When the decision was made to allow the students to remain, the government was genuinely surprised to discover the lack of controversy in the community.

The film footage this week will recall the heady days of protest, song and massacre. The students may have lacked a firm grasp of what they wanted to achieve. The detail of their demands and statements might have been poorly formulated and even crude. But what they fought for, at the heart of it, was noble: The Tiananmen Square pavements were scrubbed clean, watched and patrolled. Never again will such a demonstration be permitted. Or so the Chinese authorities say. But the stones were soaked in blood. That memory is impossible to erase. What the students were is less important than the legend that was born.

In thinking about Tiananmen and the stormy events in other parts of China, it is also worth noting that the Chinese government was more frightened by the workers’ protests than the pop star student leaders. In Beijing, and in twenty other areas of China, Autonomous Workers Unions were formed in 1989, in the midst of the students’ protests.

The leaders of those organisations were arrested, imprisoned, exiled and some executed. Most of them were unglamorous, anonymous to the Western media and unreported.

As China modernises, to the gerontocracy clinging to power in Beijing, the workers’ movement is the scariest dragon to have emerged from the protests of six years ago.

Postscript (2015)

I unsuccessfully submitted this to the Australian Financial Review and then The Australian, at the time.