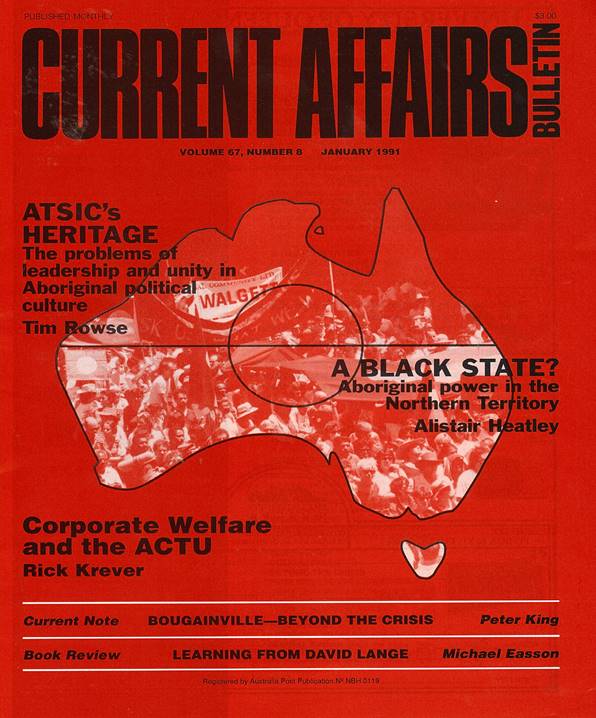

Review of David Lange, Nuclear Free – the New Zealand Way, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1990, Current Affairs Bulletin, Vol. 67, No. 8, January, pp. 29-31.

On a Saturday morning in July 1984, shortly before the elections in New Zealand, I held a morning tea at my office for two visiting US Congressmen, Stephen Solarz and Joel Pritchard. The others present were John Dorrance, the US Consul-General in Sydney, and four members of the ALP concerned about the development of the ALP’s foreign policy: myself, Bob Carr (then a back-bench member of the NSW Parliament), John McCarthy and Michael Sexton. The main topic of discussion was what changes in foreign policy might occur should Labour, under the leadership of David Lange, be elected in New Zealand.

The Australians were keen to emphasise the major differences between New Zealand Labour and Australian Labor so far as the ANZUS alliance was concerned. Everyone urged a policy of caution in the way the US might react to the New Zealand Labour Party’s official policy of repudiating support for visits to its ports of nuclear armed or nuclear propelled vessels. None of us really believed that Lange himself fully supported his own party’s stance. All of us hoped that in office the Labour government would pull back from a completely anti-nuclear stance.

Four points were made by the Australians:

First, that New Zealand Labour’s policy was influenced by the extreme left, by the widely held view in New Zealand that it faced no strategic threats and also, significantly, by the low level of debate in New Zealand public life concerning foreign policy issues. The skills of Australian Prime Minister Fraser in 1980, after the invasion by the USSR of Afghanistan, in causing damage to those in the ALP who dismissed that event as of little consequence, were contrasted with the performance of Mr Muldoon over New Zealand Labour’s criticisms of the ANZUS alliance. The damage to the ALP if it had pursued the same hostile anti-nuclear course as its New Zealand brothers and sisters would have been substantial. The various failures of New Zealand’s conservatives were particularly serious in the foreign policy area. In Australia there were significant forces disciplining the ALP – both within the party and outside on the conservative side – which assisted in influencing the ALP’s attitudes to such things as nuclear ship visits, nuclear deterrence and the ANZUS alliance.

Second, it was suggested that a major reason for the pro-Western and pro-ANZUS policies of the major parties in Australia is the strategic reality that Australia occupies a whole continent with a huge coastline washed by the Pacific and Indian Oceans. In a country with a small population, situated at the edge of Asia, most Australians believed the country vulnerable and that a firm friendship with the USA was valuable. In New Zealand, on the other hand, there was a belief on the part of many intellectuals that the Land of the Long White Cloud was remote from any aggressor and inconceivable as a target for invasion. An appreciation of the considerable differences in the strategic understanding and the political psyche of New Zealanders and Australians is important in assessing New Zealand Labour’s approach.

Third, the point was made that it would be a mistake to regard the popularity of anti-nuclear sentiment within the NZ Labour Party as purely the result of clever manipulation by extreme leftists. Such an account would overlook the insistent anti-nuclear stance of Labour figures such as Richard Prebble and Russell Marshall – both soon to become prominent Ministers in New Zealand Labour Cabinets. Marshall and Prebble were strongly influenced by their religious up-bringing and believed – rightly or wrongly – that New Zealand had a moral obligation to cease its participation in nuclear alliances. Neither men were leftists and both believed that it possible to be committed to an anti-nuclear policy and remain in ANZUS. To some degree both Lange and his Deputy Leader, Geoffrey Palmer, were known to be religiously inclined and influenced by the idea that the policy might make a moral difference – even if only by example – to the world order.

Finally, it was argued that if the worst should happen, it would be desirable that New Zealand not be seen to be punished or bullied by the Americans. Such an approach could evoke sympathy for the New Zealand stance, and undermine the pro-ANZUS constituency in Australia.

Two weeks after that pleasant discussion over morning tea, David Lange’s Labour Party was elected to power in New Zealand. Soon the speculations about how New Zealand’s foreign policy might emerge could be contrasted with the pronouncements and behaviour of the new government. All of us were surprised by the developments in New Zealand Labour’s approach. Also significant, in retrospect, was the sudden popularity of anti-nuclear sentiment in Australia – as represented in the electoral results in late 1984 and the relatively impressive performance of the Nuclear Disarmament Party (NDP) and other anti-nuclear candidates. In those elections the singer, Peter Garrett, was almost elected to the Senate in NSW as a NDP candidate; and in Western Australia, Senator Jo Vallentine won election as an anti-nuclear candidate. The success and near success of those candidates was a powerful reminder that if important policy issues are poorly debated and left alone, public opinion can shift unpredictably.

Now with the publication of David Lange’s book, Nuclear Free – the New Zealand Way, we have a fairly detailed account of the evolution of New Zealand’s anti-nuclear foreign policy. Even if there are major weaknesses in argument and style in the Lange book, it was fascinating to read and there are moments of wit which shine through, despite the usually ponderous prose. For example, I found it funny to read that the Royal Yacht Britannia, as a UK naval vessel, would no longer visit New Zealand. Lange states: “It was the policy of the British government to neither confirm nor deny whether the ships of the Royal Navy were armed with nuclear weapons. That government felt that sending Britannia to nuclear-free New Zealand would amount to a denial that the Royal Yacht was carrying nuclear weapons. Britannia, and its battery of butter knives and cocktail forks, stayed, its capacity for menace uncompromised, in its home port” [pp. 8-9].

Lange begins his book with an admission: “much of what’s described here seemed like a shambles when it happened. It would have been good when I was Prime Minister to have the luxury of thinking only about our foreign policy; but that’s not the way it works. If some of the confusion comes through the text, that’s probably what it was like.” Lange is honest enough to allow that the development of public policy and reactions to events occur in dynamic, subtle, and therefore uncertain ways. That is a refreshing admission. However, a close reading of the book also reveals that Lange was confused at critical times in the crises which marked the emergence of New Zealand as a ‘nuclear free’ country.

David Lange was Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1984 to 1989 and, subsequently, Attorney General until the defeat of the Labour administration in 1990. He served as a Member of Parliament from 1977. Obviously Nuclear Free – the New Zealand Way is written as a defence of what Lange considers to be his most significant contribution to public life. It is also an explanation of how New Zealand’s distinctive anti-nuclear foreign policy might have evolved. Interestingly, the book describes “how government and public joined together to put nuclear-free New Zealand beyond ordinary politics” [p. 8].

Lange states that he was always opposed to nuclear weapons. He describes his fear when, in 1962, the sky above Otahuhu turned blood red as a result of an American atmospheric nuclear explosion at Johnston Island, some thousands of miles away to the north east of New Zealand. He argues that the nuclear-free movement was a vehicle whereby many middle class and traditionally conservative voters became attracted to the Labour Party. He claims that in Opposition he drew a distinction between nuclear armed vessels visiting New Zealand (which he opposed) and nuclear powered vessels (which he was prepared to tolerate): “As a plain political calculation, the Labour Party might as well go in for self-immolation as say goodbye to ANZUS. I argued against withdrawal from the alliance at party conferences and delegates hissed in ritual disapproval” [p. 29].

In his public statements and private conversations – some of the most significant of which are not recorded in this book – Lange in Opposition came across as someone toughly defending ANZUS and nuclear powered ship visits. Before the 1984 elections, the former leader Bill Rowling persuaded the New Zealand Labour Party Conference that there should be a review of ANZUS by an in-coming Labour government. This suggested that a new government would not necessarily be bound by party policy. Under the NZ Labour Party’s constitution, policy was not binding on a Labour Cabinet, though abrogation of policy might be difficult.

Lange tells of his discomfort at the ANZUS Council meeting held in New Zealand in July 1984 during the transition to the new government. Not clearly revealed here is that the ANZUS partners were required by that Treaty to meet annually. Australia and the USA were anxious that the ANZUS Council meet so that the new New Zealand government would have at least a full year to work out its policies. Lange states that when he met George Shultz, the US Secretary of State, in July 1984, and earlier that year, when he met the Vice President of the United States in Washington, they skirted “around the Labour Party’s nuclear-free policy” [pp. 44; 57]. When he met Shultz in New York in September 1984, Lange states: “Nor did I say to Shultz that I would rather abandon the ANZUS alliance than lose the nuclear-free policy; I pressed the case for both”, explaining that he did not want to ‘summarily’ close off the options [p. 62]. At that meeting, Lange promised to argue within the Labour Party “that nuclear-powered vessels which were proved safe and were not carrying nuclear weapons would be allowed to visit”. Soon after his return to New Zealand, Lange publicly stated as much but quickly back-tracked after furious snubs and outbursts by nuclear-free enthusiasts:

I didn’t persist. The hard fact of it was the enthusiasts were right and I was wrong. Most nuclear-powered ships were nuclear-armed. Given the refusal of the United States to disclose the presence or absence of nuclear weapons, every nuclear-powered vessel might as well be treated as carrying nuclear weapons. In the end, I learnt that lesson [p. 63].

But when did that ‘hard fact’ become the view of Lange? Admittedly he fell silent after his floating of the ‘nuclear-powered ships can still come’ option in October 1984. But he did not then repudiate his earlier opinion. It appears that later, for petulant reasons, the New Zealand position hardened. Throughout the book, Lange complains about the military and foreign affairs establishments in New Zealand who he claims supported “continued deference to the wishes of the United States” [p. 66]. He also tries to present New Zealand as a brave country governed by an administration doggedly sticking to its principles, and his uncharitable sideswipes at the Australian and US governments are supposed to underscore that point. The book reveals with no trace of irony how sudden and capricious was the breakdown in the ANZUS alliance.

One point neither sufficiently nor clearly stated in the book was the growing antipathy between Bill Rowling, who became New Zealand’s Ambassador to Washington, and his Prime Minister. This is a critical factor in assessing US and Australian expectations of Lange’s policies. It was well known in Washington that Rowling would ‘bag’ Lange as someone completely out of his depth. Perhaps this was due in part to Rowling’s resentment of Lange’s role in replacing him as Labour leader in 1983. No wonder the Americans and the Australians became confused about the likely direction of New Zealand policy: in official meetings Lange was either coy about the ultimate direction of policy or he painfully explained his difficulties with his own party. He seemed anxious to please, not to offend the other ANZUS partners and to work out something that would settle the controversy. In December 1984, the Americans requested that, in the forthcoming March ANZUS naval exercises, a US naval vessel be allowed to visit New Zealand. The Australian Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, requested that the New Zealand government cooperate with the American request. The Americans nominated the USS Buchanan, an elderly destroyer. Lange states that “in the opinion of the government’s official advisers, it was unlikely to be carrying nuclear weapons when it made its visit to New Zealand” [p.85]. The Acting Prime Minister, Geoffrey Palmer, stated that the government would welcome a nuclear capable ship if, in the opinion of the New Zealand government, it was not carrying weapons at the time of its visit to New Zealand. But Lange refused to authorise the visit of the USS Buchanan. Ambassador Rowling caustically wrote to Lange that he had told US Assistant Secretary of State, Paul Wolfowitz: “…very frankly that I too had been taken aback by the way events had broken …I had thought …that a ship visit was something that my government could agree to” and confided that “the Americans are shaken by the speed and apparent decisiveness with which a mutually satisfactory accommodation which was in the making, became unravelled” [pp. 103-4].

What happened? Lange states that a press report in the Sydney Morning Herald, speculating that New Zealand’s acquiescence to such a visit would be a total victory for Washington, was the final crunch. That press report cited unnamed official sources in Washington. Lange claims that the reaction to that report and the humiliation which the government faced caused “a movement of opinion here which no government could have stood against” [p. 104]. Really? It is hard to escape the conclusion that at this moment of crisis Lange lost his nerve and stampeded into a tough anti-nuclear stance. It says a great deal for Lange’s political skills and the corresponding lack of skills in the National Opposition that he was allowed to get away with this volte-face and turn the new policy into a positive electoral asset. Although the book reveals Lange as someone who blundered into the stance adopted at the end of 1984, Lange was able to champion his decision as the logical and principled outcome of Labour policy.

The rest of the book is mostly dreary in contrast to the inside account of the breakdown of ANZUS. The Oxford Union debate in 1985 against the Reverend Jerry Falwell (who could wish for a better opponent!) and various other international excursions are described. Appallingly, Lange proudly repeats his boast in the Oxford debate: “We were being told by the United States that we could not decide for ourselves how to defend ourselves, but had to let others decide that for us. That, I said, was exactly the totalitarianism we were fighting against.” Exactly?! Although various US spokesmen deplored and castigated Lange’s policy, it was hardly a totalitarian terror campaign. In Lange’s period as Prime Minister, trade with the US grew and to the considerable advantage of New Zealanders.

What ended the chance of a further compromise, after the USS Buchanan imbroglio, was the destruction by French agents of the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior in July 1985. That event, which involved the loss of one innocent life, galvanized public opinion behind the New Zealand government. The book summarises the incredible, sad unfolding of the Rainbow Warrior affair. Many New Zealanders believed that to have retreated on the anti-nuclear issue would be to surrender to the kind of bastardry which the French had shown themselves capable. It is shameful that the French reneged on their word of honour concerning the imprisonment of the two agents captured and convicted by the New Zealand authorities [who were returned to France, supposedly to serve the remainder of their sentence].

Negotiations continued between the New Zealanders and the Americans to allow a ship visit by a vessel the New Zealanders could be confident was not nuclear armed. But Lange was enjoying his fame as David taking on the US Goliath. He lost interest in any compromise. Nuclear-free was now the New Zealand way.

There are a few interesting side-glances in the book which are insightful as to Lange’s thinking and behaviour. He mentions that in 1984 he discussed the unfolding of his defence policy only with Geoffrey Palmer, his Deputy, and Mike Moore, a senior Minister. This presumably left his then Defence Minister, Frank O’Flynn, out of the picture. He criticises Russell Marshall, his successor as Foreign Minister, for acknowledging in a speech that nuclear deterrence had been useful in maintaining the peace in the post-World War II era. Lange expresses his disappointment at the crumbling confidence of his Ministers as he moved around the world bragging about the New Zealand way, usually insulting the US in the process.

Lange’s book is an interesting one, an account of how New Zealand’s current anti-nuclear policy evolved. In all the circumstances it is remarkable that the Americans were as restrained as they were in their reaction to Lange’s behaviour. Australia undoubtedly had a restraining and sobering influence on US policy analysts and players. Mentioned in the book is the comment that “it always seemed to me that Australia was nearly as likely as New Zealand to go nuclear-free” [p. 156].

Despite the factors mentioned at the beginning of this review, my reading and reflections on Lange’s book convinces me that even despite strategic and moral imperatives, it is possible for a leader to make a big difference and substantially reorient party and public attitudes. Incredibly, the conservative National Party in 1986 also declared itself opposed to nuclear weapons and against nuclear-powered ship visits. With respect to the nuclear issue, this is possibly Lange’s one lasting impact on New Zealand politics. Just as certainly Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke has influenced the climate of foreign policy opinion in which any potential Australian government might operate. Lange’s book is a considerable reminder of the role of personality in the development of foreign policy style and substance.

Postscript (2015)

David Lange (1942-2005; Prime Minister of New Zealand, 1984-1989) now strikes me as half Dr Evatt, half Methodist do-gooder gone to seed, an unpleasant combination. His wit was spontaneous. Of one well-coiffured MP he once quipped in the Beehive: “The honourable member is late again. I know why. There were a few mirrors he encountered on his way. He has never walked past one he did not like.” Lange had a playful manner, which sometimes transmogrified into bombast. A sad figure in the end, he might have recalled a line from his school Latin class: sic transit gloria munde.