Published in The Sydney Realist, No. 63, November 2025, pp. 5-14.

John Anderson Archives, University of Sydney.

Very little has appeared concerning the cultured Scots suffragist and socialist activist Elizabeth or Eliza,[1] as she liked to be called, Anderson (1863-1942), mother of five – William Anderson (1889-1955), Catherine “Kate” Eliza Anderson (1891-1975), John Anderson (1893-1962), Alexander Anderson (1895-1896, who died of acute bronchitis),[2] and Helen “Nellie” Anderson (1897-1965). William and John Anderson were professors of philosophy, respectively, at Auckland University, 1921-1955, and Sydney University, 1927-1962. This article sheds new light on her story.

Like most of her female contemporaries, Eliza is a victim of historical amnesia. A perspicacious phrase of E.P. Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class (1963) is worth recalling. In that book, the author sets out to rescue from obscurity and explain “the poor stockinger, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott [Devon’s fanatical prophetess who died in 1814], from the enormous condescension of posterity.” Yet, contra to that condescension, those people, their followers, their stories, are part of history too. So is Eliza’s story. In John Passmore’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography on ‘Anderson, John (1893-1962), Philosopher and Social Critic’, he refers to the parents, Alexander Anderson (1863-1947) “a radical schoolmaster”, and “Elizabeth Anderson”, née Brown, a “teacher, pianist, and poet”. To date, that four-word tribute to her is unmatched.

From 1894 onwards, Eliza and Alexander (“Alex”) Anderson M.A. (Edinburgh), the ‘dominie’ (Scots for schoolmaster) lived near where Alex taught, at Cam’nethan Street School, Stonehouse, Lanarkshire, Scotland. Active in Scottish and British socialist circles, Alex was one of the most prominent of his era. He wrote for the socialist press and was sometimes quoted in the wider media. But his backstory, interesting though it is, need not detain us here.

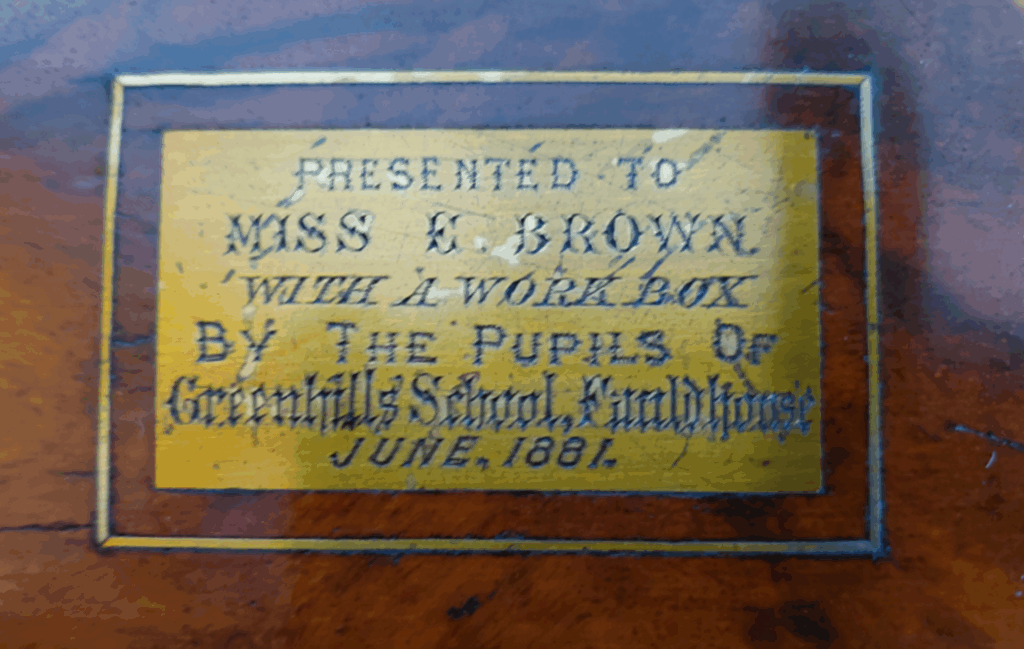

Eliza Anderson, graduate of teachers’ college, Edinburgh, schoolteacher, married Alex on 31 December 1888 at Pollokshields with Presbyterian rites; they were both 25.[3] Of “Elizabeth Brown”, Brian Kennedy, John Anderson’s biographer, says: “The Browns hailed from Fauldhouse in West Lothian, where Eliza was one of a large, close-knit family. As a student-teacher she taught at Greenhills School, Fauldhouse, West Lothian, Scotland, and the family still retains a school ‘work box’ gifted to her in 1881. In the 1870s and 1880s the area south of the Forth and Clyde Canal became industrialised with the arrival of a railway yard, distillery, paperworks, a large iron foundry, and several brickworks. In 1883 Greenhill parents petitioned Falkirk Parish School Board for a larger school. Ms Brown must have been a popular and enthusiastic teacher with a crowded primary school, to receive this gift.[4]

The dedication plaque on Eliza Brown’s writing slope. Photo courtesy of Helen Brown.

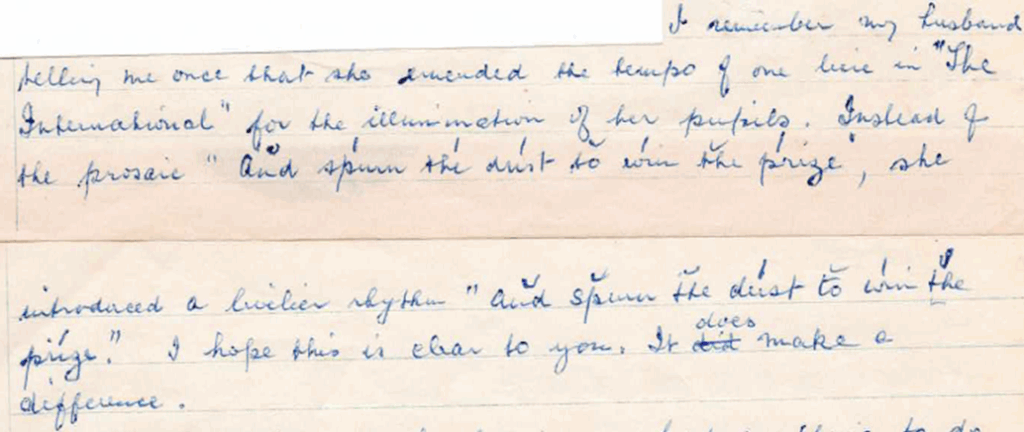

After completing teacher-training at the Glasgow Normal School, Eliza taught for some years; two of her brothers were also schoolteachers.”[5] Eliza’s father, John Brown, was a colliery manager; her mother was Catherine Brown, née Rankin. Eliza played the piano and sang Scottish and radical ballads. A great granddaughter recalls family lore to that effect. The musical traditions were carried on. A receipt for a piano purchased in 1920 by Eliza’s daughter, Helen (“Nellie”), is still to hand.[6] Eliza contributed two poems to The New Age journal, namely ‘The Grey Wolf’, published under the pseudonym ‘M.E. Brown’ (Brown being her birth surname) on 6 June 1918, and “Autumn Quiet” published under the name ‘E. Anderson’ on 8 September 1921. Janet Anderson née Baillie, John Anderson’s wife, once recalled: “Although his mother was more interested in the arts than his father, she was strongly interested in politics, too.”[7] Kennedy says: “Eliza was a fine pianist and brought a love of music and gardening to the marriage, tempering Alexander’s stern intellectualism with a lively wit and literary sensibility.”[8] Mrs Janet Anderson says: “I remember my husband telling me once that she emended the tempo of one line in ‘The International’[9] for the illumination of her pupils. Instead of the prosaic “And spurn the dust to win the prize”, she explained:[10]

Extract from holograph letter from Mrs J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 16 March 1979.

Eliza was confident in her musical acumen to adjust a hallowed, socialist tune for emphatic effect.

A perusal of British and Scottish radical literature reveals gems of interest. Eliza Anderson participated in Clarion Women’s groups, sometimes donating garments[11] and cash[12] to the cause.

The Clarion movement and its associated cycling clubs, ramblers, and holiday camps,[13] was formed by Robert Blatchford (1851-1943) in Manchester in 1890. The movement spread across Great Britain, inspiring socialist propaganda and healthy living – hence the Clarion Cyclists Clubs. Blatchford’s book Merrie England (1893) outlined a vision of a communal, cooperative, and ethical society as an alternative to competitive, capitalist individualism. The book sold in the millions including the United States and the Dominions and influenced generations of socialist activists. It was serialised in The Clarion newspaper which first appeared in December 1891 as a weekly socialist and literary journal. Selling between 30,000-70,000 copies at different times, it was easily the most read of UK radical publications in the first decades of the twentieth century. Its first issue proclaimed a “policy of humanity; a policy not of party, sect or creed; but of justice, of reason and mercy.” But it was an avowedly socialist publication, though, disillusioned with the pacifism of many Labour MPs and supporters during the Great War, Blatchford and his paper drifted rightward.[14]

Mrs Janet Anderson remarks that Eliza “once taught in a Socialist Sunday School in Stonehouse.”[15] Specific books aimed at young people featured in socialist publications, such as A.A. Watt’s The Child’s Socialist Reader (1907),[16] and F.J. Gould’s Pages for Young Socialists (1913).[17] Both of those books were illustrated by Walter Crane (1845-1915), the prolific artist and book illustrator. A contemporary of John Anderson, James McGhie, recalled of Eliza that she spoke at socialist meetings “and organised a woman’s movement in the village. She was a very quiet woman. … She would draw you out with kindness when you went into her company.”[18]

Of interest to Eliza was the formation of Clarion Socialist Sunday Schools, and Women’s discussion groups and the Social Democratic Party and British Socialist Party versions.[19] Influential with the Clarions was Dora Julia Myddleton Worrall (1866-1946), known by her penname, Julia Dawson. From 1895 to 1911 she edited the ‘Our Women’s Letter’ section of The Clarion.

Eliza Anderson’s Articles in Justice

In 1909, Eliza Anderson wrote some pieces for Justice, the monthly publication of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), the UK’s leading socialist organisation, founded by Henry Mayers Hyndman (1842-1921). Established in 1881 as the Democratic Federation, renamed in 1884 the SDF, and later the Social Democratic Party (SDP), it was Britain’s first organised socialist party. It merged with other groups to form in 1911 the British Socialist Party. Its influence was constrained by the more pragmatic, Christian-socialist-inspired, meliorist, Independent Labour Party (ILP), led by Keir Hardie (1856-1915). The details of SDF/ILP rivalry are for another time.

In 1904, the SDF formed ‘Socialist Womens’s Circles’ with the then limited aim of organising the “‘wives, daughters and sisters’ of male comrades…”[20] But the women ensured their own independent and creative presence in the movement. On 1 May 1909, Eliza was published on the SDF ‘Women’s Circles’ and their role in radicalising and informing women concerning the ills of society and socialist remedies. The editors of Justice had decided on a page or two in the publication for women, with contributions from Women’s Circle members.[21] Alongside Dora Montefiore,[22] the English Australian suffragist, feminist, and radical socialist, Eliza made her contribution. She wrote: “Previous to the establishing of the Circles only a woman here and there with exceptional opportunities could obtain a footing in the branches. Now we have the women of the rank and file co-ordinated with the men, striving for a common object — the realisation of Social-Democracy.”[23] As SDF activity proliferated, new branches were formed, as their flagship journal, Justice, reached more hands, the world seemed both smaller and closer.

Drawing on her experience in the village of Stonehouse, Anderson wrote: “Formerly, here in a Scottish village we felt remote and detached; now we are not only linked up with the whole body of our comrades in the United Kingdom, but we are equally in touch with our sisters the whole world over.”[24] The women shared in the shrinking of far horizons, networked through bonds 0f shared interests, reading and hearing of campaigns near and far.

Anderson was inspired to do something about the world crying for justice, respect, and equality. She was a feminist who understood: “It is true working women in our society [who] groan under more grievous burdens than the men of their class.”[25] Stonehouse was part of a lower-economic mining community, and the students at Alexander’s school would have come largely from this struggling working-class sector. It was a factor in both Alexander’s and Elizabeth’s socialist feelings and activities. Of womankind, Eliza asserted: “Their enslavement dates from the rise of private ownership in the means of life; their emancipation will come when Socialism puts an end to that abuse.” And she explained, “from the first, by virtue of our Socialist convictions, we have been an Adult Suffrage Society.”[26]

Anderson hoped that her experience in Stonehouse could be replicated more widely amongst women. She argued: “More than any other section of the community they need rousing —and the Women’s Circle is the agency which will best and most effectively tackle this work.”[27] But, as Eliza says, because of isolation, societal conventions made ‘women’s work’ that of “unpaid, too often uncomplaining drudgery.”[28] As Alex spent many of his weekends away giving speeches around the countryside, this placed heavier pressure on Eliza, domestically.

Three weeks later, Anderson returned to the fray, urging consideration of how to win support and understanding: “In my own case I had become convinced of women’s disabilities, social, political, and economic, in our society, and, investigating the matter, I gradually arrived at the conclusion that Socialism alone is to be the saviour of woman as of man.”[29] In developing such conviction: “The Circle meetings familiarise them with the facts of the case, and give the added zest of personal participation…”[30] Anderson urged that the men needed to make way for women activists, lamenting that, “Previously their part was to provide hospitality for propagandists, and pick up a stray crumb from the men’s conversation.” Men and the women had to work together. As Anderson put matters in her first article in Justice: “… the women of the rank and file (no longer contemptuously brushed aside or relegated to the rear as mere camp-followers) shall take their place alongside of the men, hand-in-hand, shoulder-to-shoulder, companions and comrades-in-arms, marching to the conquest of the world for the workers.”[31]

Reaching an understanding of Marxian ideas and of socialism more generally, usually occurred in stages. The SDF, more ideological than most of the other Labour sects, had to start somewhere. She wryly stated: “I think it will be admitted that it requires some preliminary mental training to make one capable of assimilating the strong meat of Marxian economics.”[32]

Suffragist, socialist, and feminist ideas permeated Anderson’s thinking. On Adult Suffrage for all, Eliza noted, “…since I joined the movement, some four or five years ago, I heard nothing about it till we formed the Circle…”[33]

Against Montefiore’s scolding of the Scottish comrades’ non-arduous campaigning for both the suffragist cause and socialism, Anderson says: “To my knowledge the members of four Lanarkshire branches turned out to public meetings, and actively opposed the advocates of Limited Suffrage, proving that in their minds Adult Suffrage is identified with and involved in the programme of Social-Democracy.”[34]

But the campaign for women’s right-to-vote was controversial within the SDF, with some of the male ‘big beasts’ of the movement adamantly opposed – E. Belfort Bax[35] and J. Hunter Watts,[36] for example. Misogyny played a part in this, including fear that the women’s vote would be more conservative than the men’s.

In Anderson’s second-last article for Justice, ‘Stonehouse Women’s Circle’, published at the end of June 1909, she obliquely addresses such critics. She refers to Mrs Bridges-Adams[37] “at our Cross”[38] who had participated in a tour organised by the Scottish District of the SDP.[39] Anderson wrote: “It is worth a good deal to see and hear this grand comrade of ours as, Boadicea-like, with commanding gestures and indignant mien, she unflinchingly demands that justice be done…”[40] The large gathering attending included cyclists and pedestrians, activists and passers-by.

At one of the Circle gatherings, a paper by Miss C.H. Jockel M.A.,[41] on ‘Endowment of Motherhood’ provoked controversy: “The discussion, especially from the side of the men comrades, reveals a great need for education on this topic.”[42] One almost hears Anderson’s exasperation.

In her final article for Justice, ‘The Impossibility of Anti-Feminism’, Anderson explicitly criticises the comrades. She begins with a flowery apology: “The unremitting struggle for the life of others, not Nature’s law, but that cunning distortion of it imposed by an unjustly constituted society… this alone is responsible for the lack of news of our circle (Stonehouse).”[43]

Anderson insists that socialism is “the ally and emancipator of woman”[44] and criticises the anti-suffragists, including Mr Belfort Bax, whose furious opposition is irreconcilable with a generous, socialist spirit. Hence the title of her piece, suggesting a true socialist abhors anti-feminism.

Perhaps Hunter Watt’s article on ‘Demos’s Dethroned Darling’[45] on former Prime Minister Lord Rosebery,[46] prompted her article. Hunter Watts pilloried “the minx” Rosebery as “irradiated” with “the feminine mind”, as if any such was weak and unpardonable.

Anderson turns the tables. Responding to Hunter Watts’s characterisation of Lord Rosebery “as a shining example of mental femininity”, she responds: “My comrades, this is a dreadful catastrophe. It completely upsets the scientific and philosophic calculations of the anti-feminists; for if Lord Rosebery has developed a female type of mind, it is just possible that, after all, women may develop a masculine type and save the day.”[47] Anderson was alert to the pathetic nonsense some of her ‘esteemed’, veteran colleagues sometimes came up with. We do not know if her critique was too much for those types, but that was the last time she authored an article in Justice. But she was still referenced as the SDF ‘Womens’ Circle’ go-to contact in Stonehouse.[48]

John MacLean,[49] the fiery BSP radical, who would later clash with Alex Anderson’s critical nationalism and support for the Great War, wrote in December 1911 about both parents: “Comrade Anderson and his wife (Stonehouse) are to be congratulated on their, or rather their family’s success. The eldest son has won his M.A. with first-class honours in mental philosophy and a bursary of £100 per annum for two years. He was second to comrade Robieson.[50] Both are ardent Social-Democrats. It also appears that the second son [John Anderson] has topped the bursary list at the preliminary examination for Glasgow University. Very soon we will expect the red flag to wave over Gilmorehill.”[51]

Kennedy says: “Eliza was a gentle and cultivated person …There must have been some difficulties in the marriage, but whether the dominie helped to drive his wife to a nervous breakdown during the First World War when her favourite son, Willie, was away at the front,[52] and to intermittent periods in an asylum, remains another tantalising family ‘secret’.”[53] Kennedy’s amateur psychologising and speculation mars what he asserts. His words “must have been” and “whether” in this quote are indicative. A breakdown, it seems did occur, the causes of which, from this distance in time, are highly speculative and uncertain. Cath Mayo, Eliza’s great granddaughter, via William and his daughter Marjorie Anderson (later Newhook),[54] says: “My grandmother Margaret, William’s wife, told my mother at some point that the nervous breakdown occurred because of the stress of caring for Elizabeth’s rather severe and demanding mother-in-law, Helen (née Redpath). There was no talk of difficulties with Alexander.”[55] This was based on conversations during Alexander and Eliza’s visit to Auckland during their world tour, stopping in New Zealand around 1924. Apparently, Kennedy says, for much of 1918, Eliza was convalescing.[56] In that time, she wrote her first poem for The New Age.

Two Poems in The New Age

One other area of accomplishment was Anderson’s poetry, as earlier mentioned.

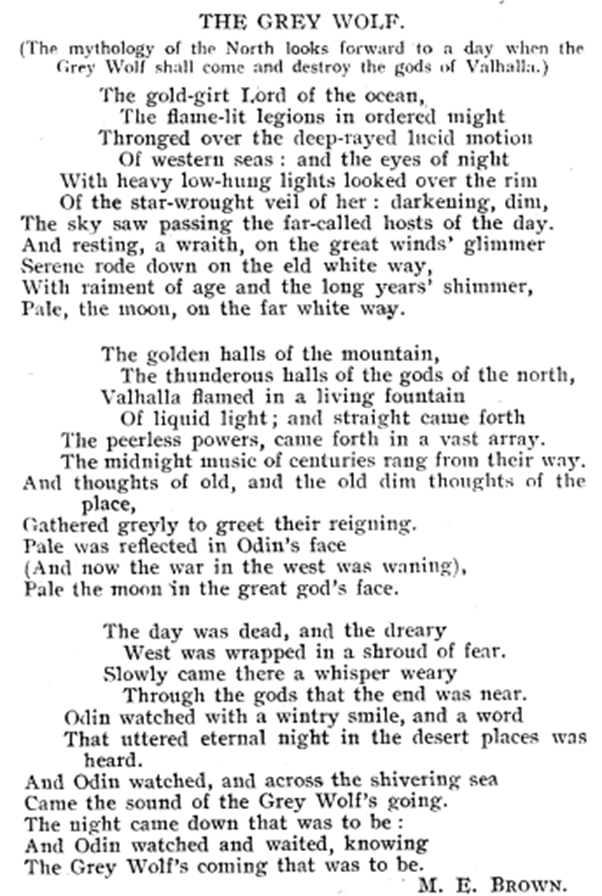

Weblin, in a sketch of the Anderson family in Scotland, notes that Eliza “in 1918 contributed a poem on the impending defeat of Germany to Orage’s The New Age.”[57] This was ‘The Grey Wolf’:[58]

This is a sophisticated poem, packed with allegories and suggesting the gods of Valhalla would be destroyed, “the end was near” as “… Odin watched and waited, knowing The Grey Wolf’s coming that was to be.” In Norse mythology, Valhalla is the hall of slain warriors chosen by Odin, feasting magnificently, waiting for Ragnarök, doomsday.

A friend, the poet and critic, Geoffrey Lehmann,[59] was consulted about Anderson’s poems. He wrote:

Anderson is an accomplished writer of verse and is likely to have written other poems which seem not to have survived. She was apparently familiar with late 19th century Rhymers’ Club poets such as Francis Thompson and Ernest Dowson. ‘The Grey Wolf’ is the more ambitious and interesting of her two surviving poems, and perhaps reminiscent of Thompson’s best-known poem ‘The Hound of Heaven’, first published in 1890, and in which the poet is pursued, and saved from a life of dissolution by divine love – the Hound of Heaven.

Anderson’s viewpoint is quite different. Her poem begins by invoking the golden flames of Valhalla in its first two stanzas. Line 2 of stanza 1 – “The flame-lit legions in ordered might” – hints that Valhalla burning may refer to war. Then, with the second last line of stanza 2 “And now the war in the west was waning”, which is in parentheses – the only such line – it becomes apparent that Valhalla’s burning is a metaphor for World War I, which by 1918, the year of publication of the poem, was now about to sputter out. Odin, the god of death and war, and king of the gods, is observing all of this. In the third and final stanza the golden flames have become “dreary”, there is a “shroud of fear” and “the end is near”. Night is falling, the “grey wolf”, Fenrir in Norse mythology, is about to arrive and destroy Valhalla, the house of the gods.

I was slightly puzzled on a first reading by references to the moon, which appear in the last lines of the first stanza, and again in the last lines of the second stanza. The moon is traditionally feminine and symbolises the cyclic nature of things, such as tides. Hence the moon presages the arrival of the grey wolf in the final stanza, and the ending of this particular cycle.[60]

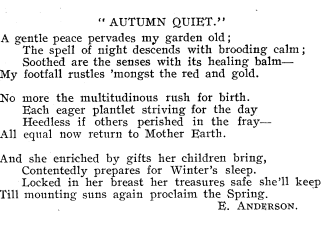

Her second poem published in 1921 was “Autumn Quiet”: [61]

Geoff Lehmann notes, “this is a much simpler poem, and again about cycles – the annual cycle of the seasons. Its language is redolent of the 1890s and more formal than that of the Georgian poets, such as Walter de la Mare, W.H. Davies, Edward Thomas and others who had begun publishing from about 1900. It has a sincere, hushed solemnity.”[62]

Anderson’s family, it seems, avidly read The New Age journal. Getting published there was a high mark of achievement.[63] Mrs Janet Anderson noted: “Mrs. A. Anderson had a short poem published in The New Age; a poem with which the editor, A.R. Orage, was very pleased.”[64] Presumably, this was the “Autumn Quiet”.[65] William Anderson appeared 15 times in the magazine and John Anderson once. The latter admired “the New Age’s solid achievements under [editor Alfred] Orage’s guidance, of its great contributions to politics and aesthetics and to the critical treatment of human problems generally.” Janet Anderson commented: “I do not know of any one person who was influential in the life of J.A. at this period, but one publication was – The New Age. This was quite a remarkable publication, dealing with social and political questions, literature, painting, music, etc., unhampered by the considerations of pleasing or displeasing its advertisers, so it was not a wealthy organisation, but it had a wealth of ideas. It had, I think, a great influence on J.A..”[66]

After Alex retired in 1924, on Eliza and his around-the-world cruise, they disembarked in various ports, including in the United States, New Zealand and Australia, to visit children and family. Not much is known of Eliza’s later years, of gardening, piano, and song. Kennedy asserts both parents joined the communist party in old age.[67] But I can find no independent verification. A great granddaughter of Eliza, Cath Mayo, relying on conversations with her mother, says that after a period of political inactivity, Eliza and Alex joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Family lore from the Willie Anderson side, is that the Andersons were instructed by the CPGB to infiltrate and report back on various labour, socialist and Church organisations with which Alexander had connections. Appalled, they resigned.[68] But, again, I wish for corroborative evidence. If Kennedy relies on John Anderson’s side of the family, and Willie’s side seems to confirm the old couple’s communist interests late in life, some connection is a useful ‘working hypothesis’. The digitising of the communist newspapers of the time has not yet been done. So, from this distance (in Australia) it is too hard to research. A great granddaughter of Elizabeth and Alex in Scotland, Helen Brown, Helen Dick’s née Anderson’s grandchild, writes:

The mentions of the Communist Party recall to mind some of Mum’s stories about her childhood which kind of back this up in a nebulous way. She always recalled being taken on Communist (she specified Communist, not Socialist) marches by her grandfather [Alex] as a very young child (she was born in late 1927 and he had retired in 1924) and him chalking slogans on the pavement. Being a tall, imposing old Victorian with a large beard, he was frequently hailed or shouted at by onlookers as “auld Trotsky”. She and my Aunt Elsie also remembered a picture of Lenin on the mantelpiece of their grandparents’ house next door, with “The Workers’ Only Hope” printed beneath it. The “l” in “Only” had been damaged or smudged in some way and forever after, he was “The Workers’ Ony Hope” to them! She also recalled her mother, my Granny Dick, being horrified when political visitors to the house referred to Elizabeth as “Comrade Anderson.” Both my granny and my mother subsequently became lifelong Tories so make of that what you will.[69]

That clinches the suggestion of communist interest of Elizabeth and Alex, but to what extent, if or when one or the other or both ‘broke’ with that perspective, we do not know. Janet Anderson says that: “It was during our last year in Edinburgh (1926) that [John] began going to Communist meetings to learn all he could about Communism; and his interest continued after we had settled down in Australia.”[70] The year 1926 was when the Great Strike occurred in the UK,[71] a galvanising event, perhaps, for both Alex and John in their political interests. Harry McShane,[72] however, suggests that Alex’s joining the CPGB came later, in 1930 “as a very old man.”[73] Though, McShane also once said: “Little was heard about [Alex] Anderson for some years. I recall him joining the Communist Party round about the time of the second world war.”[74] But, given what he published the year before, that might only highlight McShane’s faulty memory.

On 19 January 1942 Eliza died at home, where she and Alex had retired at Lesmahagow, Lanark, Scotland, next to Nellie and her family.[75] Alex departed to the shoreless shore in 1947. Of their four surviving children, William was in New Zealand (married to Margaret Summers), John in Australia (married to Janet Baillie), Katherine (married to George Murdoch) in the United States, and Helen (married to Robert Dick) in Scotland.

We can now add to Passmore’s description of Eliza Anderson a multitudinous tally: teacher, radical activist, suffragist, feminist, socialist, pianist and singer, gardener, and poet, who strained to set an example at home and wider, to use brain and imagination to better herself, family, community, and humankind.

Note on Publication: Michael Easson, on 25 October 2022, spoke to The Sydney Realists meeting in Glebe on ‘The Anderson Family in Scotland: A Radical Background’. This essay is a product of further research since then. Helen Brown, Jim Franklin, Catherine Harding, Geoffrey Lehmann, Cath Mayo, and Mark Weblin commented on an earlier version. All mistakes are mine.

[1] Hence, throughout this essay her name is mostly spelt as Eliza, rather than the given name Elizabeth.

[2] Young Alexander’s death certificate records the mother’s name as “Eliza”, as she preferred to be called. See: ‘1896, Anderson, Alexander (Statutory registers Death 656/22)’, Scottish Records Office, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk, accessed 18 October 2025.

[3] The Registrar registered the marriage on 2 January 1889. See ‘Record: 1889, 644/14/6, Kinning Park’, Scottish Records Office, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk, accessed 2 October 2025.

[4] Greenhill Scholl, Falkirk Local History Society, Greenhill School – Falkirk Local History Society. Accessed 20 October 2025.

[5] Brian Kennedy, A Passion to Oppose. John Anderson, Philosopher, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 1995, p. 18.

[6] Email: Helen Brown to Michael Easson and Cath Mayo, 19 October 2025.

[7] Letter: Mrs. J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 2 March 1978. The exchange of correspondence over several years is at: https://michaeleasson.com/articles-and-pieces-on-philosophical-topics/1978-1980-michael-easson-mrs-j-c-anderson-correspondence/

[8] Brian Kennedy, A Passion to Oppose, Loc. Cit., p. 18. I changed Elizabeth to Eliza in this quote.

[9] Eugène Pottier’s lyrics (1871) and the music composed by Pierre Degeyter (1888) were relatively simple and down-to-earth and became a rallying cry for the Socialist International in 1884 and for various anarchist, socialist and communist sects thereafter. Translations from the French varied in English. Cf. Jan Ceuppens, ‘“Die Internationale”: from Protest Song to Official Anthem and Back. Aspects of the German Reception of “L’Internationale” in the Early 1900s and After 1945’, Chronotopos – A Journal of Translation History, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2024, pp. 102-118.

[10] Letter: Mrs J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 16 March 1979.

[11] Julia Dawson, ‘Our Women’s Letter’, Clarion, 25 December 1903, p. 2.

[12] e.g., a 2s donation: Julia Dawson, ‘Our Women’s Letter’, Clarion, 12 August 1904, p. 2.

[13] Cf. David Prynn, ‘The Clarion Clubs, Rambling and the Holiday Associations in Britain since the 1890s’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 11, no. 2/3, 1976, pp. 65–77.

[14] See: Laurence Thompson, Robert Blatchford. Portrait of an Englishman, Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1951; & Tony Judge, Tory Socialist: Robert Blatchford and Merrie England, Mentor Books, 2013.

[15] Letter: Mrs J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 16 March 1979.

[16] [A.A. Watts, editor], The Child’s Socialist Reader, Twentieth Century Press, London, 1907. Cf., advertisement, Justice, 21 December 1907, p. 5.

[17] F.J. Gould, Pages for Young Socialists, The National Labour Press, Manchester/London, 1913.

[18] Letter: James McGhie to Michael Easson, 9 August 1979. This was dictated by James and typed up and sent by his son, W.J. McGhie. He was one of three ex-Alex Anderson students I was in touch with in 1978.

[19]Cf. Fred Reid, ‘Socialist Sunday Schools in Britain, 1892-1939’, International Review of Social History, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1966, pp. 18-47; Jessica Gerrard, ‘“Little Soldiers” for Socialism’, International Review of Social History, Vol. 58, No. 1, April 2013, pp. 71-96; Walter Humes, ‘Learning from the Past: An Historical Perspective on Indoctrination and Citizenship’, Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2023, pp. 18-32.

[20] June Hannam and Karen Hunt, Socialist Women. Britain, 1880s to 1920s, Routledge, London, 2002, p. 92.

[21] E. Anderson, ‘Work for Women Propagandists. Our Women’s Circles’, Justice, 1 May 1909, p. 7.

[22] Cf. Judith Allen, ‘Dorothy Frances (Dora) Montefiore (1851-1933)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 10, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1986, pp. 556-7. Allen says that “[Montefiore’s] husband died at sea on 17 July 1889. Upon learning that as the widow she had no automatic right to guardianship of her children, she became an advocate of women’s rights.” Amongst Montefiore’s publications were Dora B. Montefiore, Some Words to Socialist Women, Twentieth Century Press, Second Edition, London, 1908. Interestingly, although a SDP publication, Blatchford wrote the preface.

[23] E. Anderson, ‘Work for Women Propagandists’, Loc. Cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] E. Anderson, ‘Forward WITH the Men. Our Women’s Circle’, Justice, 22 May 1909, p. 7.

[30] Ibid.

[31] E. Anderson, ‘Work for Women Propagandists’, Loc. Cit.

[32] E. Anderson, ‘Forward WITH the Men’, Loc. Cit.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] E. Belfort Bax (1854-1926), barrister, philosopher, and socialist, championed ‘men’s rights’; he wrote the polemics The Legal Subjection of Men, Second Edition, New Age Press, London, 1908; and The Fraud of Feminism, Grant Richards Ltd., London, 1913. Cf. John Cowley, The Victorian Encounter with Marx: Study of Ernest Belfort Bax, I.B. Tauris, London, 1993.

[36] John Hunter Watts (1853-1923), barrister and activist, known as Hunter Watts or J. Hunter Watts, was a SDF, SDP, and BSP activist, close to H.M. Hyndman.

[37] Mary Bridges-Adams (1854-1939) was a British teacher, headmistress, secularist, feminist. See Jane Martin, ‘Adams, Mary Jane Bridges [née Mary Jane Daltry] (1854-1939)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004.

[38] The ‘Cross’ is a market square, allowing for public meetings. A market cross, or as Scots say, a mercat cross, is a structure used to mark the market square. Hence the abbreviate of the ‘cross’.

[39] M. Bridges Adam, ‘Feed the Children’, Justice, 12 June 1909, p. 6.

[40] E. Anderson, ‘Stonehouse Women’s Circle. Our Women’s Circles’, Justice, 26 June 1909, p. 7.

[41] Miss C.H. Jockel, M.A., participated in SDF activities. For example, delivering a talk on ‘English Literature’ to the Glasgow SDF 1906 winter classes: Justice, 13 October 1906, p. 8. Jockel also features frequently in the minutes of the Scottish Socialist Sunday Schools Conferences, 1906-1911. See: https://www.tradeshouselibrary.org/uploads/4/7/7/2/47723681/scottish_socialist_sunday_schools_1906-1911.pdf, accessed 10 October 2025. Jockel in 1910 is shown as Secretary of the Glasgow College branch of the SDF, Justice, 31 December 1910, p. 11.

[42] E. Anderson, ‘Stonehouse Women’s Circle’, Loc. Cit.

[43] E. Anderson, ‘The Impossibility of Anti-Feminism. Our Women’s Circle’, Justice, 2 October 1909, p. 5.

[44] Ibid.

[45] J. Hunter Watts, ‘Demos’s Dethroned Darling’, Justice, 18 September 1909, p. 7.

[46] Lord Rosebery (1847-1929), politician, dandy, Liberal, briefly Prime Minister, 1894-95, grew increasingly conservative, post-high office.

[47] E. Anderson, ‘The Impossibility of Anti-Feminism’, Loc. Cit.

[48] Cf. ‘Stonehouse (Scotland). Women’s Socialist Circles’, Justice, 22 October 1910, p. 12; ‘Stonehouse (Scotland). Women’s Socialist Circles in Connection with Women’s Committee, SDP’, Justice, 15 July 1911, p. 8.

[49] John MacLean (1879-1923), schoolteacher, radical turned revolutionary socialist, was famous during the ‘Red Clydeside’ era during and the years after World War I. In early 1918, the new Soviet Government appointed him ‘Bolshevik consul to Great Britain’. Of various biographies, see: Henry Bell, John MacLean. Hero of Red Clydeside, Revolutionary Lives Series, Pluto Press, London, 2018.

[50] MacLean wrote “Robertson” but meant Robieson, of whom see: Michael Easson, ‘New Boots from the Old: Matthew Walker Robieson’s Ideas and the Struggle for Guild Socialism’, PhD, UNSW, 2012.

[51] “GAEL” [John MacLean], ‘Scottish Notes’, Justice, 2 December 1911, p. 2. Gilmorehill being where the University of Glasgow is located. Nan Milton, John Maclean’s daughter, identifies “GAEL” as her father’s pseudonym. Cf. Nan Milton, John Maclean, Pluto Press, London, 1973, where Alex Anderson is mentioned at various places. I am grateful to the late Walter Kendall (1926-2003), author of The Revolutionary Movement in Britain, 1920-21, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1969, for putting me in touch in 1978 with Milton and McShane (see later). All three of their books mention Alex Anderson.

[52] William Anderson was a member of the Glasgow Branch of the National Guilds League. By June 1917 he had joined the army “and is greatly missed at our meetings.” J. Paton, ‘Glasgow, National Guilds League’, The Guildsman, No. 7, June 1917, p. 6.

[53] Kennedy, Loc. Cit., pp. 21-22.

[54] Mrs Marjorie Newhook, née Anderson (1921-2020), daughter of William and Margaret Anderson, was married to Frank Newhook.

[55] Email: Cath Mayo to Michael Easson, 16 October 2025.

[56] Kennedy, Loc. Cit., p. 22.

[57] Mark Weblin, unpublished manuscript, ‘J.A. in Scotland’. Weblin, a philosopher, was the John Anderson Research Fellow at Sydney University from 1999-2005.

[58] E. Anderson [published under the pseudonym ‘M.E. Brown’], ‘The Grey Wolf’, The New Age, Vol. 23, No. 6, June 1918, p. 96.

[59] Geoffrey Lehmann (1940- ) co-published with Les Murray his first book of poetry, The Ilex Tree (1965). The first Australian poet published by the leading English poetry publisher Faber & Faber, his Spring Forest (1992) was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. His Poems 1957-2013 (University of Western Australian Press, 2014) collects most of his poetry. He has edited five poetry anthologies and is co-author of a leading taxation textbook, written while a partner at PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

[60] Email: Geoffrey Lehmann to Michael Easson, 17 October 2025.

[61] E. Anderson, “Autumn Quiet”, The New Age, Vol. 29, No. 19, 8 September 1921, p. 228.

[62] Email: Geoffrey Lehmann to Michael Easson, 17 October 2025.

[63] John Anderson, ‘Amazing Journalists’ [Review of Peter Selver’s Orage and the New Age Circle], The Observer [Sydney], Vol. 3, No. 23, 12 November 1960, pp. 30-31.

[64] Letter: Mrs. J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 2 March 1978, Loc. Cit.

[65] Janet Baillie married John Anderson on 30 June 1922 and may not have known of the earlier poem.

[66] Letter: Mrs. J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 2 March 1978, Loc. Cit.

[67] Kennedy, Brian, Loc. Cit., p. 21. I do not find everything Kennedy says to be reliable, especially concerning Janet Anderson’s memory and interpretations of Scottish radical politics.

[68] Email: Cath Mayo to Michael Easson, August 18, 2011; this account relies on conversations between Mayo and her mother, Mrs. Majorie Newhook, née Anderson, then still alive.

[69] Email: Helen Brown to Michael Easson and Cath Mayo, 19 October 2025.

[70] Letter: Mrs. J.C. Anderson to Michael Easson, 2 March 1978, Loc. Cit.

[71] Called by the Trades Union Congress, the peak body of unions in the UK, the Great Strike went for nine days, 4 to 12 May 1926, to (unsuccessfully) resist reductions in wages and conditions for coal miners. In a voluminous literature, see Keith Laybourne, The General Strike of 1926, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1993, & Alastair Reid & Steven Tolliday, ‘The General Strike, 1926’, Historical Journal, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1977, pp. 1001-1012.

[72] Harry McShane (1891-1988) was a BSP member, contemporary of John Maclean and joined the CPGB in 1920, and became a leading British Stalinist. He knew the Anderson family. See: Tom Crainey, ‘Harry McShane: The Last of Red Clydeside’s Defiant Dreamers’, The Scotsman, 14 April 1988, p. 13.

[73] Harry McShane with Joan Smith, No Mean Fighter, Pluto Press, London, 1978, p. 65.

[74] Letter: Harry McShane to Michael Easson, 17 March 1979.

[75] Cf. The Registrar registered “Elizabeth” Anderson’s death on 20 January 1942. See: ‘Statutory Registers. Deaths, 649/13’, Scottish Records Office, Loc. Cit.