Published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 2017, https://www.smh.com.au/national/jim-baker-leader-of–bohemian-circle-sydney-push-argued-philosophy-over-an-ale-20170317-gv0cvb.html

Allan James “Jim” Baker, who has died aged 94, was one of Australia’s more interesting philosophers, intellectuals, and gadflies. He was a prominent member of the Sydney Push, the Bohemian intellectual circle that met in Sydney’s city and inner-city pubs from the late 1940s.

Celebrated and mourned in Anne Coombs’ book Sex and Anarchy: The Life and Death of the Sydney Push (1996), the personalities that moved in and out of the Push orbit included Paddy McGuinness, Wendy Bacon, John Olsen, Keith Looby, Robert Hughes, Frank Moorhouse, Lillian Roxon, Germaine Greer, Clive James, and many others.

Baker added intellectual credence to his colleagues, who prided themselves on debating, criticising, and endlessly disputing life – the examined and unexamined. Not that everyone agreed or had similar views. Indeed Baker thought Coombs did not understand properly that there were distinct and sometimes overlapping perspectives. Indeed, the logical relation between the terms “Sydney realist philosopher”, “Libertarian” and “Sydney Push” member is that of intersection. Baker was one of the relatively small number of people where all three converged. He continued writing, entertaining and thinking to the end of his days – in recent years, frequently contributing to The Realist newsletter.

Born on 22 July 1922 at Woolloomooloo, to Kenneth Baker, a farmer from Gunnedah and Mary Frederika Baker (née Cross), bartender, from Moree, he was never far from poverty in his youth. Scholarships and several inspiring teachers encouraged him to pursue studies and what bloosomed into a stellar academic career.

His father, ruined by the seasons and the Great Depression, sold his land, briefly became a publican and ended up working on tramways in Sydney, then as a country fettler, repairing railway lines and sleepers. Young Jim, attending 18 schools, sometimes none, devoured books from the travelling ‘Railway Library’ that occasionally visited.

In 6th class at Bogan Gate, a teacher saw talent and urged application for a scholarship to Wolaroi College, Orange. Baker attended as a boarder. Then, in 1935, he attended Sydney Boys High School until, in the last two years, Marist College, Hamilton, a suburb of Newcastle, near his father’s work where he had secured a permanent position.

Good Leaving Certificate results secured a bursary for an Arts degree at Sydney University where Baker discovered a passion for Philosophy under John Anderson (1897-1962), the Challis Professor of Philosophy at Sydney University from 1927-1958, who was a polarising figure both in life and death.

Gaining in 1944 First Class Honours in both Philosophy & History, Baker was awarded the University Medal. Exempted from military service, his first academic position was in History at the Sydney University College located in Armidale in 1945. He and Violet Hilvardine “Hilva” Cordner, completing her honours year in Psychology, became close. She too went to Armidale to complete her Dip Ed for teacher qualifications.

In 1946, Baker took up the Wentworth Travelling Scholarship to Oxford to study at University College for the two year B.Phil. The young couple married there and later lived in Dundee, Scotland, where Baker was a teaching Philosophy fellow. A position came up for a lecturership at Sydney University; he successfully applied, returning in 1951, becoming a leading light in the Sydney Libertarians and the Sydney Push.

In 1965 he took up the inaugural Chair as Professor of Philosophy at Waikato University in New Zealand. But, missing Sydney, returned at the end of 1968 as Senior Lecturer at Macquarie University, later meeting his second wife Mairi Grieve. Eventually, he retired as Macquarie’s Professor of Philosophy in the 1980s.

He had sabbaticals at UK, US, and New Zealand universities. When in London he stayed in the Soho area, as there were nearby expatriate Push pubs, as in Fleet Street, for those living there or visiting.

Baker lined up with the libertarian strain of Anderson’s thinking, a tendency he interpreted and several of A.J. Baker’s books systematically expound this philosophy.

In Australian Realism. The Systematic Philosophy of John Anderson (1986),

Baker wrote that his “book outlines the realist and pluralist philosophy of John Anderson, Australia’s most original thinker…” And that the task was necessary as “Anderson never gave an overall account of his views”. Partly, as Jim Franklin in his history of philosophy in Australia, Corrupting the Youth (2003) notes, Anderson’s refusal to “engage with new trends in philosophy overseas… led to Sydney philosophy developing into a small and isolated pond”, which left Anderson an obscure and difficult philosopher to understand, let alone interpret.

For an original, creative philosopher, as was Baker, to be known primarily as the interpreter and defender of another’s work may not seem to be the accolade to die for. Yet Baker’s defence and exposition of John Anderson’s thinking was no mere summarising. The act of explaining ideas and concepts to a new audience required intellectual accomplishment of the highest order. The late David Armstrong (1926-2014), perhaps Australia’s most original and influential philosopher, thought Baker’s interpretation of Anderson an extraordinary achievement. He told me that he and other philosophers were able for the first time to approach Anderson with a clear and comprehensive framework.

On Baker’s social and political philosophy, his Anderson books were presented as a “powerful and potentially revival position”. He argued towards the end of Anderson’s Social Philosophy: The Social Thought and Political Life of Professor John Anderson (1979), that the Libertarian Society at Sydney University, from the early 1950s to the late 1960s, “combined Anderson’s pluralist social theory with [Max] Nomad’s notion of permanent opposition”. That is to say Baker in those works, and also in Social Pluralism: A Realistic Analysis (1997), drew from Anderson’s distinct tradition and added his own thought, including ideas from the anarchist philosopher Max Nomad, into a distinctive identity, Sydney Libertarianism.

Baker was not only an academic philosopher. He proposed that Libertarians were pluralists, non-servile, free-thinking atheists, supporters of sexual freedom and “opponents of repressive institutions, particularly that great destroyer of independence and initiative, the political state”. What all that meant entailed hours of debate, discussion, including with opponents (Catholics included – the Push wasn’t entirely cultish), preferably over an ale – hence the jocular notion of “critical drinking”. As a leader of the Sydney Push, he inspired and co-founded the Sydney Libertarians and their publications, including The Sydney Line, as well as Heraclitus, Broadsheet, and The Sydney Realist.

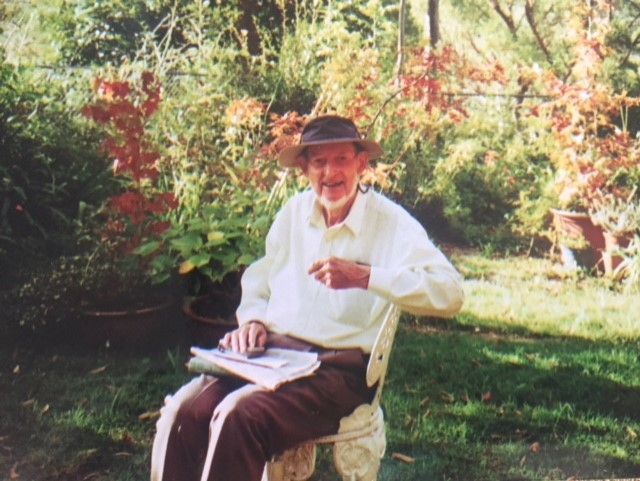

Baker developed a love of cricket, horse racing, parties, folk songs, jazz, and beer. He was a clever and wily tennis player. His daughter, Jenny, noted that although he was a raconteur who loved a drink in a particular Push pub, he also liked long periods of solitude when he would go away and stay in the “Bush”, sometimes having a drink at the local watering hole, sometimes abstaining for weeks. The “Bush” was often Old Bar or Harrington on the mid-north coast.

He is survived by his wife Mairi Grieve; daughter Jenny, and grandchildren. His first wife died in 2015 and a son, Stephen, died of motor neurone disease in 2014.

Postscript (2018)

What was published in the Sydney Morning Herald was a much truncated version of the above. I have added some of what was edited out. I understood from the acting editor of the obituary page that with so many worthy obituaries space is at a premium.

Baker was someone I disagreed with on so many levels. But his approach to life and philosophy was intelligent, coherent, and worth thinking about. He was a model of fearless inquiry, even if I considered some conclusions and arguments unpersuasive. It was a delight to know him, even if slightly.

He made some helpful suggestions on my Robieson PhD and, especially, encouraged me to keep going.