Published in The Northern Line, an on-line journal dedicated to the life and work of John Anderson, May 2013, pp. 10-14.

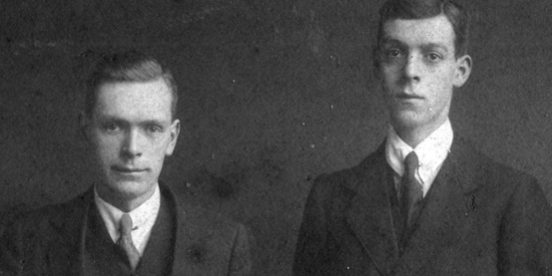

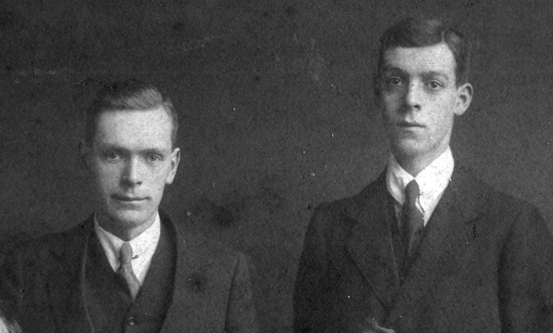

In a brief assessment of the Philosophy Department at Auckland University, Robert Nola comments on Professor William Anderson (1889-1955) that:

Unlike his brother, William published only a handful of papers, several being concerned with issues in education. In his obituary on Anderson, his successor Anschutz attempts to summarise Anderson’s views on philosophy. 135 He tells us that Anderson understood it to be ‘the theory of practice’, that he held that ‘philosophy is co-extensive with political theory’ and that ‘education was for him primarily a matter of politics’. Though William’s broad claims need much unpacking, they do initially stand in contrast to the view of his brother John in which critical inquiry is essential to education, its aim being to challenge traditions and to replace opinion by knowledge. Little has been done to investigate the similarities and differences between the views of the two brothers. But it is evident that William’s impact on philosophy at Auckland stands in an inverse relation to the considerable philosophical impact of his brother on philosophy and the broader academic community in Sydney.136

This low assessment of William Anderson’s influence on philosophical studies in his adopted homeland is reinforced by Dr. Charles Pigden, then a Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Otago, New Zealand, who gave a paper in 2008, in Auckland, lamenting that New Zealand got “the wrong Anderson” – implying that Australia was lucky to get John Anderson (1893-1962), Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney from 1927 to 1958, instead of that ‘dull dog’ brother.

William Anderson’s daughter, Marjorie Newhook, and her daughter Catherine Mayo were in the audience for Pigden’s talk. In contrast to the paper delivered and the advertising of his address, which confused William Anderson with Francis Anderson137 [no relation], Pigden saw the humour in the printer’s mistake.

Mrs. Mayo wrote:

Last year’s [2008] Auckland Writers and Readers Festival presented a public lecture on the history of philosophy in New Zealand called ‘Getting the Wrong Anderson’.. Mum and I went. At question time, I attempted, very briefly, to put forward another view of my grandfather. But before you get too excited about my knowledge of William’s mind, I was a baby when he died, so our philosophical conversations hadn’t really taken off. Most of my information is drawn from Gavin Ardley’s account…138 After the lecture, we were approached by Robert Nola, a professor in philosophy at Auckland University who is currently writing another history of the Philosophy Department to update or supersede Ardley’s. He was eager for any material we might have on William, but as Robert was a close friend of Keith Sinclair’s and subscribes to the standard views, my mother decided not to give him her nose scrapings, let alone any information. Somewhat Scottish, but that’s the background.139

Dr. Pigden eventually published his corrected paper.140

The background to Anderson’s appointment is that Auckland University College wanted to expand and be considered a serious place of learning. Several senior appointments were required. In 1920 Auckland College agreed that then philosophy, economics and history lecturer Joseph Penfound Grossman141 should be relieved of several teaching tasks and that a Professorship Philosophy be established. Anderson, who had graduated with first class honours in moral philosophy and logic from Glasgow in 1911 and who had lectured in Logic there from 1912 to 1920, was appointed. Anderson’s title from 1921 to 1924 was Professor in Mental and Moral Philosophy. After 1925 the position was converted to a Professorship in Philosophy, with the understanding that the subjects of psychology and political studies (effectively the history of political ideas) were part of the domain of philosophy. William took up the professorship, occupying it to his death in 1955. Surprisingly, perhaps, William never applied for the more prestigious Sydney post when that position become vacant in 1926, on the unexpected death of Bernard Muscio. By then his children had been born and the family were well settled. William apparently encouraged his younger brother to apply for Sydney.

In the John Anderson Papers at the University of Sydney there is some evidence of William’s experiences in New Zealand. For example, in a letter by William to his brother written in March 1921, he observed:

So now we have been 3 weeks in Auckland. You ask for my first impressions… I think I am confirmed in my expectation that the ‘freer life of the Colonies’ would prove a myth. I should say that the people here are much more conventional, or have much less reason to superadd to convention, than at home. Of course they go in greatly for taking holidays on every possible occasion. (I am ‘free’ for the week already – Easter), & are devotees of the ethics of ‘a good time’. That consists largely in going to races (horses & yachts) & in playing cards, & picnicking. But nobody anywhere that I can see has any appreciation of liberty. (Damn few at home, either, of course, but still they occur). Here they have, for instance, a censorship142 which prevents the importation of ‘Bolshevik’ literature, & which the Prime Minister (Bill Massey143) refuses to take off…144

This suggests a liberal outlook, resentment about busy-bodying government presuming to know best, and opposition to the prevention of ideas being discussed. Unfortunately his area of teaching, in the subject areas of Ethics, Logic and Psychology, was handicapped by a lack of resources. William Anderson noted:

Then there is the difficulty of getting text-books. Suppose you want to make a change, you would have to do it about a year in advance so that the booksellers here could get the books out. So I’ve to work away, for this year at any rate, on Jevons145 & Meltone in Logic, & James’ smaller book on Psychology.146 Still in the elementary stages it doesn’t matter too much.147

Even at this point, early in the period of his academic appointment, William was considering what to teach and the role he should pursue at the University, commenting that:

The present curriculum gives an all round degree, & the reforming people seem to be moving in the direction of a sort of specialisation which is only possible or desirable in a different type of institution. I think one has to make up one’s mind that a University here must be more of a teaching than a research institution, so far as the students are concerned. (See the distinction M.W.R. draws in his appendix to Hobson).148 Here you have a University which is strong on being ‘democratic’. The classes are mostly held at night, attended by people who are working, or in training as teachers thru’ the day. No doubt you only get the real ‘academic’ life if you have full time students. But if you set up a self-complete University of the type of Oxford or Cambridge in a country whose total population is little greater than Glasgow, running it so as only to admit people who can give their full time to it, it is doubtful if one college could be kept open.149

Anderson, from the mid-1920s sought appointment to the University Academic Board and thereafter became Chairman. From this largely academic-administrative post, Anderson combined teaching tasks with university management.

This is not the place to embark on a critique of William Anderson’s time at Auckland. To do such an assessment requires a detailed scrutiny of the relevant archives, which are incomplete, lacking W. Anderson’s papers. As Nola suggests much ‘unpacking’ is required. But, as discussed below, there is literally little original material to evaluate, let alone unpack.

On the conventional assessment of his reputation, perhaps three points can be made. First, W. Anderson argued for educational standards articulated from a robust perspective. As was highlighted by Anschutz, William Anderson was regularly involved in education controversies. In his 1943 talk on education ‘reforms’ in New Zealand his main objection to the proposed compulsory core curriculum was that it would result in a ‘levelling down’ effect for academic students.150 In his pamphlet ‘The Flight from Reason in New Zealand Education’ Anderson prophesised that only parents wealthy enough to send their children to Australia or England would be able to gain “what has hitherto been the right of all, a grammar-school education.”151 By mid-1944, the Catholic hierarchy, assisted by Anderson, had narrowed the focus of its criticisms to two aspects of the Report: the values of ‘new education’ and the lowering of academic standards.152 Towards the end of his life one observer noted that “his criticism of contemporary educational methods are obviously related to his views on morality and freedom, and his distrust of much of contemporary philosophical teaching.”153

Second, even where he disagreed with particular points of view, for example Anschutz’s communist leanings and the content of certain student publications, W. Anderson believed in the right to self-expression. For example, of Phoenix magazine, published in the Great Depression years.154 Though note that Hercock claims that Open Windows, a student journal published in the 1930s was sent to William Anderson as Chair of Professorial board, but the “issue was thereafter banned by them.”155

Third, W. Anderson made clear to his brother John that he thought that academics best not be involved in active political controversies, especially from a partisan point of view. Perhaps this stance signalled a change in his thinking from his Glasgow days. It also showed alarm that John Anderson’s political sympathy for communism and active involvement in the Communist Party of Australia in the late 1920s invited potential dismissal by the University authorities.

As for the absence of William Anderson’s papers, they can be accounted for in the circumstances of his death. On Thursday July 28, 1955 William Anderson gave a paper on ‘The Moral Philosophy of Science’to the Rotorua Philosophical Society.156 The following Saturday week, he travelled alone to the family holiday home for the weekend and died there, apparently in his sleep, of thrombosis. In the John Anderson and family papers, is a letter from William’s wife, Margaret (“Meg”) Anderson, to Professor John Anderson explaining the circumstances of William’s death:

Dear John,

I thought you would like to know just what happened. Willie cancelled his Melbourne trip not on account of ill health. It may have been because he was too late in making arrangements. He seemed very well but I noticed he was tired especially towards the end of the heavy mid-term. On top of this he was asked to give a paper to the Roturua Phil. Soc. When I saw him labouring over its preparation I said couldn’t he just give a rehash of something he had already done but it appeared that they had asked him to speak on a particular subject. This he wanted to clear up in his own mind. He drove there in the car, stayed over-night & came back the following day in time to give a 4 o’clock lecture. In spite of his brake failing at Hamilton he made the journey (80 miles) on the handbrake – a gruelling experience but he never spared himself. The impression I got was that he had enjoyed himself but he did say he was glad that was over. The following Friday we went to a play in the college hall… Next morning he went to Waiheke. Before I could point out that the weather forecast was bad he said “I must go this weekend. The storekeeper will think I am never going to pick up what I ordered five weeks ago.” He went off as brisk as usual. I don’t go down there much as I find it very tiring. From what the residents down there have said he went down to the beach in the afternoon. Mrs. Nugent watched him climb the hill very slowly…157

The next morning, Sunday August 8, 1955, William Anderson was found dead in bed. His grand daughter wrote that:

[There’s] an account my mother gave me a few weeks ago about his last day on Waiheke. He owned an old 12-foot, clinker-built whaling dingy, which had to be hauled up and down the beach near the beach – I remember it well from my childhood. It sat in our old boatshed, far beyond our strength to shift. And as he was mad-keen on going out in it, he had probably man-handled it by himself prior to walking up the hill to get himself home. My mother blames the boat for causing the thrombosis.158

William Anderson’s papers and books were at his University office. Meg was distraught at the unexpected death and for not being there. She was unable to organise the funeral; the University did. Meg did not attend.159 It appears that in this turmoil and lack of clear direction from the family, that all of William Anderson’s papers were disposed of or otherwise lost.160 R.P. Anschutz161succeeded William Anderson as Professor of Philosophy and took over his office soon after his death. He was already due to do so within a few months anyway. Meg Anderson’s letter also states: “John [Anderson, son of William, in New Zealand] & Anschutz have cleared his study at College without finding the address he gave at Sydney.162 We will go through carefully the masses of papers that have accumulated here. Anschutz is willing to look after it.”163Alas, the “masses of papers” are lost. Although there are newspaper clippings about William Anderson and other background material in the University of Auckland archives, none of his personal papers are currently held there.

William Anderson’s family appear suspicious of strangers, perhaps as a result of the ‘treatment’ of William Anderson by several academics. For example, Professor Keith Sinclair’s History of the University of Auckland164 refers to William Anderson and suggests that he was both a deadweight and an utter reactionary. Sinclair had not even been aware that Anderson had read Marx. Sinclair once wrote that “when I knew him he was politically and educationally the most extreme conservative in a very conservative place. I once asked a question about Marx and he refused to discuss Marx saying that he was beyond the pale of western civilisation. He did, however, discuss Hegel with enthusiasm.”165 William Anderson, who from 1915 to 1917 wrote on Marx, Georges Sorel and guild socialism for Alfred Orage’s The New Age journal, was no stranger to Marx’s ideas. One can imagine Anderson’s impish grin as Sinclair listened.

The evidence does point to a change in political thinking. William Robieson (1890-1977), the great, anti-appeasement policy editor of the Glasgow Herald, from 1935 to 1957, and a student contemporary, wrote that: “Those who had known Anderson in his days as a Glasgow student and as a young lecturer… found it illuminating on his last visit to Scotland [in 1952]… enlarge with eloquence on the unhappy consequences of excessive majority domination in New Zealand bodies as different as the wharfingers and the teachers’ professional organisation.”166 On the contrary, opposition to centralisation and undemocratic control was one of the consistent themes of William Anderson’s political outlook. But that is another story. He was no dull dog, even if his mark on the history of philosophy was negligible.

Postscript (2018)

I now wonder whether some of the William Anderson papers were sent by Anschutz to Sydney and that this would account for some of the material in the John Anderson Archives at the University of Sydney. If this be true, then it might have been William’s brief notes on those articles of M.W. Robieson that he had wished to collect into a book, rather than Professor John Anderson’s summary.

135. R.P. Anschutz, ‘In Memoriam: William Anderson’, The Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 33, No.3 (December, 1955): pp. 139-142.

136. Robert Nola, ‘Auckland, University of’, in Graham Oppy and N.N. Trakakis, editors, A Companion to Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand, Monash University Publishing, on-line version (2010). R.P. Anschutz, ‘In Memoriam: William Anderson’, The Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 33, No.3 (December, 1955): pp. 139-142.

137. In 1890 Francis Anderson (1858-1941) was appointed as Sydney University’s first Professor of Philosophy – the Challis Professor of Logic and Mental Philosophy. He was one of Professor Edward Caird’s graduates and assistants, graduating M.A. from Glasgow in 1883. See W.M. O’Neil, ‘Anderson, Sir Francis (1858-1941)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7, Melbourne University Press, Parkville (1979), pp. 53-55.

138. Gavin Ardley, Sixty Years of Philosophy, A Short History of the Auckland University Philosophy Department 1921-1983, University Bindery, Auckland (1983).

139. Email: Mrs. Mayo to Michael Easson, December 15, 2009. Sinclair’s view of William Anderson is discussed below.

140. In modified form this was published as Charles R. Pigden, ‘Getting the Wrong Anderson? A Short and Opinionated History of New Zealand Philosophy’ in Graham Oppy and N.N. Trakakis, editors, The Antipodean Philosopher: Public Lectures on Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand, Lexington Lanham, MD (2011):pp. 169-196.

141. Grossman later became professor of history and economics at Auckland University College, until dismissal from his professorship in 1932. The grounds included defrauding William Anderson of money. See Rachel Barrowman Mason, The Life of R.A.K. Mason, Victoria University Press, Wellington (2003): pp. 211-212.

142. For a brief history of censorship in New Zealand see Chris Watson and Roy Shuker In the Public Good? Censorship in New Zealand, The Dunmore Press, Palmerston North (1998).

143. William Ferguson Massey (1856-1925), farmer and conservative politician, popularly known as “Farmer Bill”, co-founded the New Zealand Reform Party in 1909 and served as New Zealand’s Prime Minister from 1912 to 1925. An early biography was H.J. Constable, From Ploughboy to Premier: a New Life of the Right Hon. William Ferguson Massey, P.C., John Marlowe Savage & Co., London (1925).

144. Letter: William Anderson to John Anderson, March 27, 1921.

145. See W. Stanley Jevons, Logic, Macmillan & Co., London (1886) and W. Stanley Jevons, Elementary Lessons in Logic Deductive and Inductive , Macmillan and Co, London (1893).

146. See William James, Psychology, American Science Series Briefer Course, Henry Holt and Company, New York (1904) and William James, Talks to Teachers on Psychology: and to Students on some of Life’s Ideal , Longmans, Green and Co., London (1910).

147. Letter: William Anderson to John Anderson, March 27, 1921.

148. i.e., M.W. Robieson, edited by William Anderson, ‘On the Reorganisation of University Education’, Appendix in S.G. Hobson National Guilds and the State, G. Bell & Sons, Ltd., London (1920): pp. 363-400.

149. Letter: William Anderson to John Anderson, March 27, 1921.

150. See Jenny Collins, ‘Criticisms and accommodations: The Thomas Report and Catholic secondary education in New Zealand’, a paper presented at the NZARE/AARE Conference Auckland, November-December 2003.

151. Anderson’s 1943 talk to the Catholic Teachers’ Guild was converted to a pamphlet. See W. Anderson, ‘The Flight from Reason in New Zealand Education’, Auckland (1944): p. 7.

152. The arguments were: First, the Catholic hierarchy argued that the ‘new education’ values implied in the Report would signal an increase in secular values in secondary education and a consequent move away from traditional beliefs and disciplines fundamental to Catholic schools. Second, they feared that the new curriculum would result in a lowering of academic standards and thus threaten the rights of academically able Catholic pupils to higher education and access to public service positions, which had been guaranteed via the public examination system. See K. O’Reilly, ‘Roman Catholic Reactions to the Thomas Committee Report’, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 12 (1977): pp. 124-127; R. Openshaw, G. Lee and H. Lee, Challenging the Myths: Rethinking New Zealand’s Educational History, The Dunmore Press, Palmerston North (1993) and G. Lee and H. Lee, H., Making Milner Matter: Some Comparisons Between Milner (1933-1936), Thomas (1944), and Subsequent New Zealand Secondary School Curricula Reports and Developments, Paper presented at the NZARE, Massey University (2002).

153. Jonathan Bennett ‘Philosophy in New Zealand’, Landfall, Vol. 7, No. 3 (September, 1953): p. 198. This article is based on Bennett’s observation of the first meeting of the New Zealand Philosophical Congress. Of his style, Bennett notes that: “Professor Anderson knows the art of obtaining forgiveness from those on whom he jumps so entertainingly.”

154. Phoenix magazine appeared in two distinct volumes during 1932 and 1933, published by the Auckland University College Literary Society. Hamilton notes that there was “a respect for academic freedom and freedom of speech, even among some who strongly disagreed (the late Prof. William Anderson, for instance).” See Stephen Hamilton, ‘The Risen Bird: Phoenix Magazine, 1932-1933’, Turnbull Library Record, Vol. 30 (1997): pp. 37-64, and Stephen Hamilton, ‘Red Hot Gospels of Highbrows: R.A.K. Mason and the Demise of Phoenix’, Kōtare, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1998).

155. Fay Hercock, A Democratic Minority, A Centennial History of the Auckland University’s Students’ Association, Auckland University Press, Auckland (1994): p. 53. There are too few details to go by here. What is definite is the presumption of the editor of Open Windows, Bennett, that William Anderson would be likely to be impressed by the journal.

156. See ‘Annual Report for 1955’, Rotorua Philosophical Society, published in Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1956-57, Volume 84 (1957). The Report notes: “It is with regret we record the death of the late Professor Anderson a short time after his visit to Rotorua, and we extend our sympathy to his widow and family.”

157. [Handwritten Aerogramme] Mrs W. Anderson to John Anderson, August 18, 1955, in University of Sydney Archives, P.42 Papers of John Anderson and family, Series 19, Item 2.

158. Email: Cath Mayo to Michael Easson, February 2, 2010.

159. William Anderson was buried with Presbyterian rites, his funeral held at St Andrew’s Church – “just across Symonds St from the main Auckland University campus. His death was very sudden and unexpected, and my grandmother was so shaken by it, she felt unable to organise it or even attend. The University took over, and as they had not yet built the University Maclaurin Chapel, where interdenominational and secular services can be held, they presumably picked St Andrew’s because he was Scottish.” Email: Cath Mayo to Michael Easson, December 15, 2009.

160. Optimistic hopes that they were put into boxes and placed somewhere in a library’s stacks and completely forgotten are dashed. Enquiries with the University of Auckland have drawn a complete blank.

161. Anschutz, a New Zealander of Jewish stock, who was for a period close to the communist party, wrote a noted study on Mill, partly based on his PhD at Edinburgh under Norman Kemp Smith. See R.P. Anschutz, The Philosophy of J.S. Mill, The Clarendon Press, Oxford (1953). See references to Anschutz in Rachel Barrowman, A Popular Vision: The Arts and the Left in New Zealand 1930-1950, University of Victoria Press, Wellington (1991).

162. This being a reference to a paper W. Anderson had given to a conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy.

163. Letter: Mrs W. Anderson to John Anderson, August 18, 1955.

164. Keith Sinclair, A History of the University of Auckland 1883-1983, Auckland University Press & Oxford University Press, Auckland (1983).

165. Letter: Keith Sinclair to Michael Easson, March 26, 1981.

166. William Robieson [published as “W.R.”], Obituary: ‘Anderson, Professor William’, The College Courant, Journal of the Glasgow University Graduates’ Association, Vol. 8, No. 15 (Martinmas, 1955): p. 58.