MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson, 7.1.78

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

I am writing a M.A. (Hons.) thesis on the social and political thought of your late husband, Professor John Anderson, for the School of Political Science at the University of NSW.

I would greatly appreciate an interview to discuss several aspects of your husband’s life in Scotland and some other biographical matters.

Looking forward to your reply.

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 19.1.78

Dear Mr. Easson,

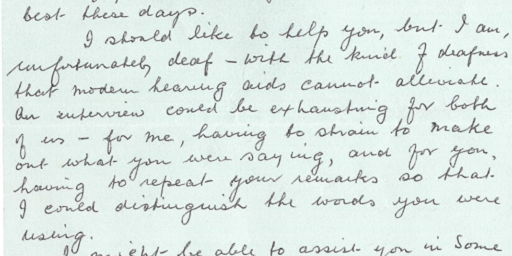

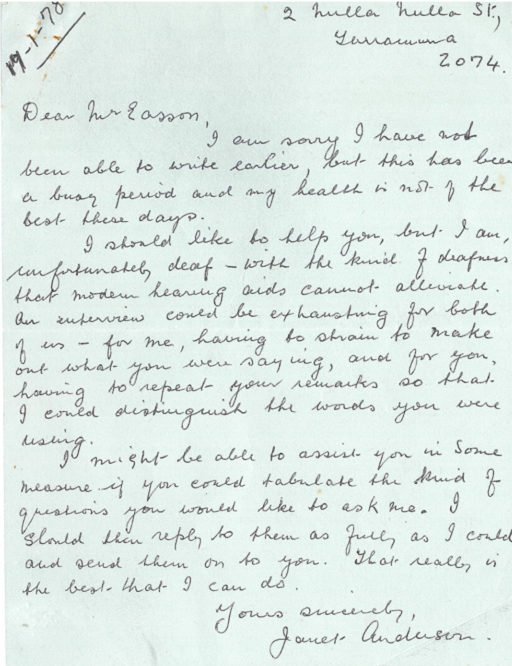

I am sorry I have not been able to write earlier, but this has been a very busy period and my health is not of the best these days.

I should like to help you, but I am, unfortunately, deaf – with the kind of deafness that modern hearing aids cannot alleviate. An interview could be exhausting for the both of us – for me, having to strain to make out what you were saying, and for you, having to repeat your remarks so that I could distinguish the words you were using.

I might be able to assist you in some measure if you could tabulate the kind of questions you would like to ask me. I should then reply to them as fully as I could and send them on to you. That really is the best that I can do.

Yours sincerely,

Janet Anderson

MBE to Mrs J.C. Anderson, 3.2.78

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

Thank you for your reply of 19/1/78. In this letter I shall, as you suggest, tabulate a number of questions which I would like to ask you about Professor John Anderson’s life before arriving in Australia.

The matters that I raise are sub-divided into various subject headings.

John Anderson’s Family

a) What was the Christian and maiden name of John Anderson’s mother?

b) What was the address of John Anderson’s parents and relatives in Scotland? Did Professor Anderson or yourself correspond with your relatives in Scotland? If so, have you retained any of those letters?

c) One hears stories about the anti-clerical attitudes of J. Anderson’s father, Alexander Anderson, that he sometimes demonstrated outside of church-halls on Sundays. How true is this story?

d) What do you believe were the main political influences acting on John Anderson before he matriculated?

e) What teaching subjects did John Anderson’s father teach? Did Alexander Anderson ever teach at University level? What was the thesis topic of Alexander Anderson’s M.A. thesis?

Undergraduate Days

a) I understand that John Anderson wrote articles for the student journal Glasgow University Magazine under the pseudonym “Jude”, and edited the Glasgow University Magazine in 1918. Was there any significance to the pseudonym “Jude”?

b) Did John Anderson write for any other undergraduate journals? (Did the Fabian or Socialist Societies produce a journal?)

c) How active was John Anderson politically during his undergraduate days? What were the undergraduate clubs or societies that he was a member of?

d) Have you retained material relevant to Anderson’s political involvement during this time? For example, I wonder whether the text or notes of any contribution that John Anderson made to undergraduate societies have been preserved?

e) Who do you believe were most influential on John Anderson politically at this time? Were any of his university lecturers significant in this respect?

f) What was the subject of John Anderson’s M.A. (Hons.) thesis? What was the topic of your thesis?

After Graduation

a) I understand that During World War I John Anderson tried to enlist. On what grounds was John Anderson rejected for service?

b) During John Anderson’s career as a lecturer at Glasgow, Cardiff and Edinburgh Universities did he write anything on social and political subjects? Do you know whether J. Anderson was politically active at this time?

William Anderson

a) What was William Anderson’s politics? Did he write for The New Age journal? (Did Mrs. Anderson, John and William Anderson’s mother, ever write for this journal?)

b) What was William Anderson’s address in Auckland, New Zealand? Are any of his relatives still alive?

c) Did W. Anderson help financially to put J. Anderson through university?

d) What personal relations did John Anderson enjoy with his brother? Did they correspond regularly?

Revival of Political Interests

a) Donald Horne, in an article on John Anderson, states that in 1926 John Anderson’s interest in socialism revived during the British General Strike and that he admired the Communist Party’s opposition to the ‘sell out’ of the workers by the trades union leaders and parliamentary Labour Party. These events, according to Donald Horne, stimulated Anderson to study the works of Lenin. (Cf. Donald Horne ‘John Anderson: University’s Stubborn No-man’, Daily Telegraph, September 14, 1946, p. 15). How accurate is this appraisal of John Anderson’s political awakening?

b) How active was Anderson politically from 1917, after he completed his M.A. (Hons.) degree at Glasgow, to 1926? In what way was J. Anderson active during the General Strike in 1926? Did J. Anderson, at this time, join any political organisation? Did he join the Communist Party of Great Britain?

Reason for Migrating to Australia

a) What were the reasons for your husband taking up his appointment in Sydney? (I would imagine that migrating to a distant city in a distant land would have been somewhat daunting for the both of you). When you arrived in Australia was it your intention to settle permanently in Australia or did you think that you would always return to Scotland to live? In the ‘Anderson Archives’ held in the Fisher Library at the University of Sydney there is a letter by Professor Samuel Alexander to John Anderson dated 24/12/26 which contains the remark: “I hope by the way your wife has no ill will against me for being a contributory cause of your change of life”. What do you make of this statement? Was Samuel Alexander influential in determining your “change of life” (by departing for Australia)?

Looking forward to your reply,

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 2.3.78

Dear Mr. Easson,

Here is the best I can do for you now that my memory is not so good as it once was; nor have I now the time or the energy to dig for any supplementary information. As far as possible, I have replied to your questions in the order in which you have asked them, though I cannot for the life of me see how much of the biographical material you require can help you to evaluate or describe the political and social theories of John Anderson!

John Anderson’s Family:

a) His mother’s name was Elizabeth Brown.

b) His mother’s family was located in Fauldhouse, Midlothian. His father was an only child, and I never knew the particular address of his parents who were both dead by the time I got to know J.A.’s family. But they were “east-country” folks, too, i.e., south-east of the Forth & Clyde Canal. Old Mr. Anderson was a shepherd. Yes, we corresponded with our relatives – regularly, at first, but more desultorily as time went on. If any letters survived, they survived by chance. I cannot lay my hands on any at the moment.

c) Alexander Anderson, to my knowledge, never “demonstrated” outside Church Halls on Sundays or any other days. He did lecture on Socialism, indoors and out-of-doors, on Sundays as a rule, since that was the one workless day for most workers.

d) The main political influence on J.A. before he matriculated was that of his parents, I should say. Although his mother was more interested in the arts than his father, she was strongly interested in politics, too.

e) His father began teaching in a small school at the little village of Port Logan on the Mull of Galloway in Wigtownshire. The two older children were born there, but by the time J.A. was born, his father had been appointed headmaster to one of the two schools in Stonehouse, a village on the edge of the uplands in Lanarkshire. Neither school taught beyond the Qualifying Examination, and Mr. Anderson continued at Cambusnethan School until his retirement. His pupils were well known for their ability in mathematics – or should I say arithmetic at this stage?

Undergraduate Days

a) Whether I presumed it or was told it, I have always thought that the pseudonym “Jude” was taken from Hardy’s novel – Jude, the Obscure, but not having read that particular volume for about 70 years, I am unable to verify the fact – or find out what the connection (if any) might be.

b) Neither – so far as I know. I may say here that Scottish Universities were not so well provided with funds as Australian Universities seem to be now. The G.U.M. had to pay for its own production by its sales; nor were the students so well supplied with cash as they seem to be now.

c) I do not know how active J.A. was politically during his undergraduate days, nor what clubs or societies he joined. He attended such meetings & discussions as interested him, but what papers he gave (if any) I do not know.

d) See above. No such material has so far been found among his papers.

e) I do not know of any one person who was influential in the life of J.A. at this period, but one publication was – The New Age. This was quite a remarkable publication, dealing with social and political questions, literature, painting, music, etc., unhampered by the considerations of pleasing or displeasing its advertisers, so it was not a wealthy organisation, but it had a wealth of ideas. It had, I think, a great influence on J.A..

f) My thesis was in English, and I think it was on Tennyson, but on what aspect of Tennyson, I have not the vaguest remembrance. Nor do I remember all that J.A. was required to present for his Honours Degrees – both in Arts & Science. I was told, for my deafness prevented me from being at any of them, that one lecturer at the recent Commemoration Lectures said he had never seen so many and such high qualifications as my husband had, in any applications for a post in a University.

After Graduation

a) Patriotism, I suppose – his own brand of it, neither Samuel Johnson’s nor jingoism – plus a good deal of what Arthur Koestler mentions in one of his articles, namely, a desire to stand by his countrymen. His “crowd” all went to enlist, his mother’s youngest brother was fighting in Flanders and his own brother was training at Aldershot.

There was some trouble with his eyes which bothered the authorities, and his physique was far from robust. He was classified as “fit for service at home only”, and he was quite loquacious on the subject of route marching and drilling. I never heard him mention any other duties.

b) Not so far as I know.

William Anderson

a) I do not know what W.A.’s politics were – some form of Socialism, I should imagine. He did write several articles for The New Age, some on the question of National Guilds which S.G. Hobson was also discoursing upon in The New Age. And yes, Mrs. A. Anderson had a short poem published in The New Age; a poem with which the editor, A.R. Orage, was very pleased.

b) W.A. lived in the suburb of Remuera in Auckland. His three children, two daughters and one son, are still alive.

c) I never inquired, but I should think not. J.A. was a First Bursar in the University Entrance Examinations in 1911 & I should imagine he would have quite a little income of his own.

d) Quite brotherly, I should think, and they corresponded at intervals.

Revival of Political Interest

a) J.A. had a life long interest in politics, and it might be more correct to say that a definite interest in Communism showed itself during and after The General Strike, for just such reasons as those given by Donald Horne. Like all people interested in politics, he had been stirred by the advent of Keir Hardie, but he was not much attracted by the S.L.P. (Socialist Labour Party) which believed that the workers’ lot would be bettered by strong Parliamentary representation. The branch he (and his family) favoured was the S.D.P. (Socialist Democratic Party) which believed the workers could themselves better their lot by education & more education. Then, in 1926, followed his interest in Communism.

b) I’m not quite sure just how much you mean by “politically active”. He was always interested in politics but I do not think he ever held office in any branch of whatever party he was interested in. The impromptu “demos” of this day were not a feature of University life or of political life in the first decades of the 20th Century. But he attended political meetings, took part in discussions and read what literature he could lay his hands on. It was during our last year in Edinburgh (1926) that he began going to Communist meetings to learn all he could about Communism; and his interest continued after we had settled down in Australia. He was never a member of the Communist Party either here or in Great Britain.

Reason for Migrating to Australia

a) Well, J.A. was looking for a professorship; he applied for the post in Sydney and he was offered it. The fact that his brother was in Auckland may have had some influence on him, but I think he was psychologically in need of “fresh woods and pastures new”. We made no definite plans for the future – or even indefinite ones. We seized the opportunity – afterwards we would see. At least there would be a Sabbatical Leave in a few years, & we were quite contented with that. As a matter of fact, he took his first Sabbatical in 1938, and during all the years he was to lecture, he took only one other one – and that he spent in Australia! In spite of a few contretemps of one kind or another, there was never any question of his returning to Scotland or of his seeking another post. He liked it here, and here he would stay as long as he could.

I have never understood the fuss people make of that unfortunate (?) remark in Prof. Alexander’s letter. It must be the “literal-mindedness” of the Australian – not a bad thing except that it sometimes prevents an imaginative grasp of a situation. I think you might have understood it if you had followed to its end your thought that it might have been a “daunting” thing for both of us to contemplate migrating to a place where we would literally be strangers in a strange land. (As a matter of fact, we found two old school fellows quite soon. Both had married Australian soldiers of the First World War, but one was in Melbourne and the other in Cessnock – quite remote from Sydney, and we had no communication with either since our school days). Professor Alexander could have understood that I, who had never been out of Scotland in my life, might have more mixed feelings about leaving family and friends and familiar things than my husband might have, especially since he was going to a post for which he felt ready: but I had enough of the adventurous spark in me to want to see a new country, as well as have a glimpse of the strange ports at which the ship would be calling. I certainly made no demur about leaving Scotland, and I had no “ill-will” to anyone. By accepting the offer of the post, we ourselves had made the choice. By naming himself as “a contributory cause of our change of life”, Professor Alexander may have been referring to the fact that he was one of the committee that interviewed my husband in London in connection with the Professorship. And so I think the remark was a humourous one, made by a man I had never met, but who has been described to me as a kindly one.

Perhaps, before finishing, I might do well to explain what I mean by “his own brand” of patriotism. At one political meeting he was asked what he meant by “patriotism”. The exact words escape me but his answer was to the effect that patriotism could be described as such an attachment to the culture of one’s country that one was ready to defend it at any cost.

I am sorry I have taken so long to reply to you, but there have been many interruptions these holidays; and I hope you will excuse the corrections, etc. If I took time to prepare a fair copy for you, I just don’t know when you would get it.

I hope this will be of some use to you, and best wishes for your success.

J.C. Anderson

MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson 12.4.78

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

Thank you for your reply dated the 2nd of March. Your letter provides more than enough biographical information relevant to my evaluation of the social and political theories of John Anderson.

In this letter I shall tabulate a number of questions which I would like to ask you about Professor John Anderson’s political activities during the period of his involvement with the Communist Party of Australia and the Trotskyist movement. As in my last letter, the matters that I raise are sub-divided into various subject headings.

Contacts with the Communist Party of Australia

a) How and with whom did John Anderson develop contacts with the communist party after his arrival in Australia?

b) John Anderson’s contributions to the journal The Communist were written under the pseudonym ‘A. Spencer’. Was there any significance to this pseudonym?

c) How active was John Anderson in the Friends of the Soviet Union (F.O.S.U.), the United Front Against Fascism (U.F.A.F.) and the Educational Workers’ League?

d) In his article ‘Politics and Publicity’ published in the Workers’ Weekly newspaper in October 1927, John Anderson mentions that he wrote three letters to the editors of the Sydney Morning Herald on the Sacco-Vanzetti controversy, and that only one of those letters was published. Have the other two letters been preserved?

The C.P.A. in 1929

a) How deeply was John Anderson involved in the fraction fighting in the Communist Party of Australia (C.P.A.) which, in 1929, led to the defeat of the so-called “notorious right-wing” leadership led by Jack Kavanagh, and the victory of the new leadership comprising a triumvirate of Hebert J. Moxon, who became General-secretary of the C.P.A., J.B. Miles and Lance Sharkey?

b) What issues were there against the leadership of Jack Kavanagh?

c) How well did J. Anderson know the leading figures in the C.P.A., Kavanagh, Moxon, Miles and Sharkey?

The Comintern Representative and the C.P.A.

a) In April 1930 a new force made its presence felt within the C.P.A. with the arrival in Australia of a representative of the Comintern, an American, Harry M. Wicks, who went under the name of Herbert Moore. For reasons which are not entirely clear to me, H.J. Moxon was purged as General-Secretary of the C.P.A.. Do you know for what reasons Moxon was removed as General-Secretary of the C.P.A.?

b) What were J. Anderson’s relations with H.M. Wicks, alias Herbert Moore?

c) What were the chief reasons for John Anderson’s break with the C.P.A.? Over what period did this take place?

Censorship and the C.P.A.

a) In 1932 the Melbourne University Labour Club refused permission to J. Anderson to publish another article in their journal Proletariat. There is a cryptic reference to the circumstances surrounding the Proletariat’s censorship in an article published in the Workers’ Weekly in 1932:

After sending his rejected article to Proletariat a messenger, connected to King, came to the office and told us about it. Later Anderson came to the office, and contrary to his practice during many months, chatted (fished) for an hour. The a friend decided that he would take the matter up with Anderson [presumably, the censorship by Proletariat], but, when he stated his business, Anderson curtly asked, “Have you a message?” The comrade had no message – we do not fear professorial lackeys – therefore he was shown out. The connection is clear.

‘Why Professor Anderson Attacks the C.P.’ The Worker’s Weekly November, 1932

b) What do you make of this statement? Who is the person ‘King’ mentioned in this statement?

c) In this article in the Workers’ Weekly, referred to above, it is also alleged that the editor of the Communist journal in 1928 rejected “an attempt by him [i.e., J. Anderson] to use its pages to attack Marxism”. During 1928 the editor of this journal was J. Kavanagh who published several articles by J. Anderson under the pseudonym A. Spencer. Is there any truth to the claim that in 1928 the Communist refused to publish one of J. Anderson’s articles?

John Anderson and Trotskyism

a) When did J. Anderson first read of Trotsky’s criticism of Stalinism? Besides Trotsky’s writings, who were the other theorists which J. Anderson read which influenced him to critically support a Trotskyist position?

b) What part did Anderson play in the writing of the pamphlet The Need for a Revolutionary Leadership which was published by the Workers’ Party (Left Opposition) of Australia?

c) In this pamphlet, The Need for a Revolutionary Leadership, it is stated that “the present right-wing leadership of the C.P. of A. [is] composed of right-opportunists censured by the E.C.C.I. [Executive Committee of the Communist International] in 1929”. Do you believe that the leadership of the C.P.A. in 1933 could be described as right-opportunists?

John Anderson’s Break with Trotskyism

a) What factors decided John Anderson’s break with Trotskyism?

b) During J. Anderson’s sabbatical year, in 1938, I understand that the both of you travelled to the United States of America and contacted a number of philosophers and prominent ex-Trotskyists. Who were those people?

c) How influential were Max Eastman and Sidney Hook on John Anderson’s thinking in regards to developments in the Soviet Union and Trotskyism?

d) How deeply were you involved during John Anderson’s association with the C.P.A. and the Trotskyist movement?

Looking forward to your reply,

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C Anderson to MBE, 7.5.78

Dear Mr. Easson,

I am glad my last letter was of some use to you. I fear that this reply to your later request will be rather unsatisfactory. Most of the events to which you refer took place very soon after our arrival and the process of settling in was not very easy. We had to recover from the effects of the voyage, find a house as speedily as possible so that we could have all our books around us, and get accustomed to the climate – social, academic and meteorological; and it was natural that I should see to things about the house and gardens as far as I could, and leave my husband free for his new position, and whatever activities he had to, or wished to, engage in. You seem to have access to a good deal of information, so I should advise you to check as carefully as you can the information included in this letter.

Contact with the C.P.A.

a) The same as he did in Edinburgh – go to the Communist Bookshop which was then in Sussex St. and begin from there. There was also later The Basement Bookshop in George St. where he got many publications, leftist among others.

b) Not that I know of, but our son has the theory that it originated in “Marks and Spencer”, the name of an emporium in London and that his father, who delighted in word play, would get some satisfaction in suggesting that the “A. Spencer” came after Marx.

c) He was naturally interested in these, attended such lectures and meetings as he had time for, but had no official position.

d) If any do exist, I have not so far come across them among his papers.

The C.P.A. in 1929

a) J.A. was involved, but how deeply I do not know.

b) I cannot enumerate the particular issues, but as is so often the case in politics, it was Left v. Right, with J.A. on the Left, I think.

c) He knew them as well as one would know men with whom one was in frequent touch at political meetings or discussions.

The Comintern Representative and the C.P.A.

I think I’d better take this section all in one piece. I do not remember particular facts or the order in which they come, but my interpretation of them remains, and you may be able to verify it from the facts you have ferreted out. I believe that Moscow was alarmed at what was taking place in Australia. They recognised that J.A. was something to be reckoned with, & sent Wicks (Moore) and his wife to do the reckoning and cleanse the party of disturbing elements. At first, they were not particularly welcome. I gathered from one of the women communists who told me that Mr. & Mrs. Moore were too fond of throwing their weight about. However, they succeeded in getting rid of Moxon, and getting the comrades generally “to toe the line”; so much so that one of them, hitherto very friendly with both of us, attacked him in the W.W. as the Solomon of Sydney University, accusing him of being an “academic lackey”, etc., etc.. The form of this attack pointed to the fact that it was not J.A.’s politics that worried them so much as his philosophy. And it was about this time that he criticised adversely Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. If he did it publicly, I don’t remember when or where, or whether he had just talked about it among the comrades. But I do remember his saying at an open meeting in Phillip St. Hall, that while with their philosophy he did not agree, with their politics and economics he did. As I said above, I do not remember the order in which these events occurred, but that was the general commotion in that lively time.

Censorship and the C.P.A.

a) What I make of your quotation in this section is that it was a pure concoction: it has all the ear-marks of a “made-up” story; and I should be surprised if it ever happened – in that particularly conspiratorial form, at least.

b) I don’t remember anything about that at all. But there was an article “Censorship and the Working-Class Movement” which some Melbourne Club (Labour, I think) refused to print. It caused quite a commotion at the time, and I think the W.E.A. in Sydney printed it in pamphlet form. There should be some around. If I could lay my hands on one, I’d send it to you, but I had someone helping with the papers some time ago, & since then I have not got properly re-oriented myself.

John Anderson and Trotskyism

a) I do not know just when J.A. read certain books – or any books at all. But as Lenin was dead and had not been very satisfactory (though some said that his New Economic Policy would have proved salutary if he had lived to carry it out), and Stalin was discredited as much by his own actions and those of his supporters, as by his detractors, Trotsky had to be investigated. Other than Max Eastman and Sidney Hook, I remember only Borkenau whose work on the Spanish War was most interesting.

b) I don’t know what part – if any – he played.

c) I haven’t a clue.

P.S. There was a Jack Sylvester (of Balmain) with whom J.A. was in close touch during this period. I never saw him (J.S.).

J.A.’s Break with Trotsky

a) Briefly, I should say, he came to realise that Trotsky’s version contained the seeds of dictatorship even as that of the others did – though he was the most intellectual of the trio.

b) Of the American trip I can tell you nothing of political or philosophical value. A howling gale on the Atlantic crossing knocked me completely out, and J.A. made contact by himself with politicals and philosophers alike, while I struggled with doctor’s orders all the way across America. It took me months after we got home to regain some of the strength I had lost.

d) I cannot tell you how influential Max Eastman and Sidney Hook were. My husband was an original and independent thinker who sought to find out for himself “how things were” – not superficially but thoroughly. In reading these men, he was seeking corroboration for some of the ideas that had formed in his mind – how, why, when or where it is impossible to say – as much as he might be gaining fresh ideas from their works. Even people with whom he disagreed could have had an influence on his thinking! It’s not so simple.

d) You can see for yourself that I was not very active politically. I had neither the desire nor the energy for a public life, but in the background I did whatever I could to support my husband – even if such action sometimes included adverse criticism of his activities!

Sincerely yours,

J.C. Anderson

MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson, 9.10.78

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

Thank you for your letters which have provided very useful biographical information about Professor Anderson.

There are several matters I should have raised in my previous letters which I list below.

(i) What were the names of Professor William Anderson’s children? Do you know where they are now living?

(ii) Did you have any brothers or sisters? If so, what were their names? Do you know whether any of them are still alive and where they are now living?

(iii) John Anderson’s last article for the Glasgow University Magazine was an editorial commenting on the effects the War had on university life. In his editorial Anderson states an opinion which I hope you might be able to illuminate; referring to the ‘disproportionate’ number of female and medical students at Glasgow University, Anderson states:

Whereas the women students can do nothing to restore the old régime or to keep things going as far as possible, the men in medicine will do nothing, being interested in athletics and other trivialities, useful enough as trimmings to an ordered scheme but of no account as the substance of student activities.

Editorial, Glasgow University Magazine, May 15, 1918, p. 188.

This passage raises the issue of the participation (or lack of it) of female students in university life at Glasgow. What do you make of this editorial? How did you find university life at Glasgow University? Did you write for the Glasgow University Magazine? If so, did you use a pseudonym? During your time at Glasgow University what percentage of students were female?

Since I have researched this topic I have discovered that John Anderson’s father, Alexander, was an important and very controversial figure in the socialist movement in Scotland. I have recently received a letter from a Mr. Jackson who was a former student of Alexander Anderson. He states that Alexander Anderson supported Britain’s part in the Great War, left the British Socialist Party over the issue and supported Lloyd George’s coalition government. He states that Alexander Anderson grew disillusioned with the government and eventually joined the communist party. Do you know anything of this? Did John Anderson ever comment on any of this? Jackson, also states that John Anderson, his brother William, sister Kate and a few friends, including Jackson and his sister were involved in a small socialist study group devoted to the scrutiny of various socialist literature. This would have been around 1910-1911. Do you know anything of this?

With kind regards and looking forward to your reply,

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 20.10.78

Dear Mr. Easson,

You are insatiable and you intrigue me! What the names of Willie Anderson’s children – and even W.A.’s children themselves – have to do with John Anderson’s social and political theories (which you told me was the subject of your proposed thesis) I don’t know and I can’t imagine. But it’s your pigeon, and I’ll give you what information I can, though you must remember you are getting the memories of an old woman verging on 86, which are not nearly as clear and definite as she would like them to be.

(i) The names of W.A.’s children are Marjorie, Elspeth and John, in that order. What the married names of the girls are, I do not know – if I ever heard them, but I have a notion that the eldest married a scientist and the younger one an engineer. John eschewed an academic career, and a love of horses led him in an agricultural direction, I think. Where they are all living now, if not in N.Z., I do not know.

(ii) Yes, I have a sister and a brother living, both younger than myself, and both retired. My sister, Margaret, now a widow, keeps house for my brother Willie who, when he retired, was Art Master in East Kilbride High School. My sister, incidentally, was a primary school teacher. They now live in Hamilton, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

(iii) J.A. and I went up to Glasgow University in August, 1911, the beginning of the academic year in Britain. At that time there might be said to be still a hint of sufferance and, perhaps, patronage on the part of the men students & various authorities, to the presence of women in university life: but the women continued to come up. Perhaps an example of this might be found in the production of the G.U.M. itself. It was predominantly the men’s stamping-ground – one issue each academic year being allotted to the women students. In the academic year 1917-1918, the last issue but one was produced by the women, and a perusal of that might have given you some idea of the reason why the women could do little “to restore the old régime or even to keep things going”. In passing, I might remark here that the G.U.M. had to justify its own existence – i.e., it got neither subsidies nor grants nor levies from anywhere – it had to be interesting enough for the students to buy it. And it usually was. The same held for every other student activity so far as I know: if a student wished to participate in any activity not connected with his or her course of study, then he or she had to pay the requisite fee or subscription and that was that, and applied to sports of all kinds.

As to the proportion of women to men, I cannot say. When I went up in 1911, it must have been pretty small, but in 1916 it must have been much greater, though in 1918 it needn’t have been so great owing to the return of medical students to the University. I cannot at this date give you particulars of the various government regulations concerning reservations, but I know that the medical students were generously dealt with.

If you read through the editorials of 1917-1918, you would have found that J.A. had all through been voicing the thought that in the exigencies of war, the University would be dragged down into the marketplace; and also the fear that, if such a thing happened, it would be hard for it to regain its old position – that of the custodian of learning and knowledge. The Arts Faculty had always been the centre of University life and now it was very sorely depleted. He even feared for the continued existence of the G.U.M., which was a magazine of some distinction. His prognostications were to some extent fulfilled, but the results were nothing like the havoc wreaked on educational standards by the Second World War, so that Education (and the Universities with it) has gone all to pieces.

21.10.78

I do not know whether what I have been saying illuminates things for you: much may depend on what your ideas of education and the position of a university in the community are. It has seemed to me for some considerable time that the equality which a bewildered democracy claims it is seeking to achieve, is only to be gained by a lowering of standards. The prevalence of “elitist” as a denigrating word speaks for itself: a letter in yesterday’s Herald refers to the “sacred cow of university autonomy”, while today’s issue contains several pieces which simply appal me.

However, that’s not getting on the with job of answering your questions. I find, on re-reading what I have written, that I have forgotten to tell you that I never wrote for the G.U.M.. Why, I cannot tell. Perhaps just diffidence – perhaps because I travelled daily to & from the University and felt vaguely that while I could be said to be at it, I was not of it – perhaps because I was “hung up” on some literary questions that did not leave my mind free to produce the kind of material the G.U.M. required. Anyway, there it was.

Of the year 1910-11, I can tell you little so far as the Andersons were concerned. John and Kate were at Hamilton Academy in my day, but they were paying students while I was a Junior Student, and the classes were separate. (The Junior Student system had supplemented the old Pupil Teacher system of having teachers, and a County Committee, newly-formed, took the place of the Old School Board. Pupil teachers used to begin classes at 8a.m.; from 8a.m. to 10a.m. they had lessons, and then from 10a.m. to noon, and again from 1p.m. to 3p.m. they assisted in various class-rooms, until at 3p.m. they reverted to pupils themselves and had further lessons until 5p.m.. As Junior Students they remained students until they got the Higher Certificate, when they went on to the Teachers’ Training College (Scottish Normal) or the University. At a fee-paying school, they got their fees paid through the County Committee). As I didn’t get to know J.A. at all well until our 3rd or 4th years at the University, I know very little about what happened in Stonehouse around 1910-1911. It was a lively little village, whether due to the presence of Mr. Anderson or not, I don’t know, and produced musicians, singers, discussion groups, etc.* Mr. A. was a well-known socialist speaker, but I don’t think I ever heard him described as a Communist, either by outsiders or by any member of the family, and it wasn’t until about 1925 that J.A. himself began taking a serious interest in Communism. However, Mr. Jackson may be right. The name “rings a bell” – I’m sure I’ve heard the Jacksons of Stonehouse mentioned, but in what connection I cannot now remember. I’m sorry I can’t be more definite about this section, but you understand, perhaps, that the village where the Andersons lived & the one where I dwelt were at least 3½ miles apart; trains, though reliable, were rather scarce and there were neither telephones nor motor cars in either village. The mail service was excellent, but even the best one has its limitations, and so, consequently, were the comings and goings between the two places somewhat limited.

With best wishes, and hopes that this information will be of use to you.

From J.C. Anderson

*All on an amateurish scale – the village produced no prima donnas so to speak, but the interest and the activity were there

MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson, 20.2.79

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

I am afraid that this letter raises some more questions that may strike you as curious.

My purpose, by asking questions, is to obtain an exact record of John Anderson’s life. Some of the questions raise matters peripheral to my thesis, but I think it is useful to solve biographical problems which might trouble researchers of the future. (Most of the information I have gathered will eventually be deposited in the Anderson Archives).

(1) To your knowledge, was Alexander Anderson related to Tom Anderson, the founder of the Socialist Sunday School movement?

(2) Did John Anderson lecture in Political Economy (or other subjects) to Workers’ Educational Association (W.E.A.) classes in Edinburgh or other places in Scotland?

(3) I know that John Anderson signed some of his articles ‘J.C. Baillie’, but I wonder whether you were the author of any articles bearing this signature. I have enclosed a copy of an article which appeared in The Communist journal in 1928. The article demolishes V.F. Calverton’s Marxist interpretation of Shakespeare’s works. The article is signed ‘Janet. C. Baillie’ – did you write this article? (This article is not mentioned in the Select Bibliography of John Anderson’s published writings compiled by Professor J.A. Passmore in Studies in Empirical Philosophy).

(4) I have come across a reference in the N.S.W. Investigations Branch files of the 1930s to Professor John Anderson. In one file there is an allegation that in 1938 Anderson was seen visiting Port Kembla and collecting information on ship-building and industry so as to send this information overseas. It is also mentioned in the file that Anderson communicated with the notorious Russian Trotsky. Apparently the ignorant author of the report was unaware of the politics vis-à-vis the U.S.S.R.. The story on this file is, of course, amazingly absurd. I wonder what grain of truth served as the basis to this mount of ‘mis-information’. As a matter of interest, did Professor Anderson visit Port Kembla in 1938 or thereabouts?

Looking forward to your reply.

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 16.3.79

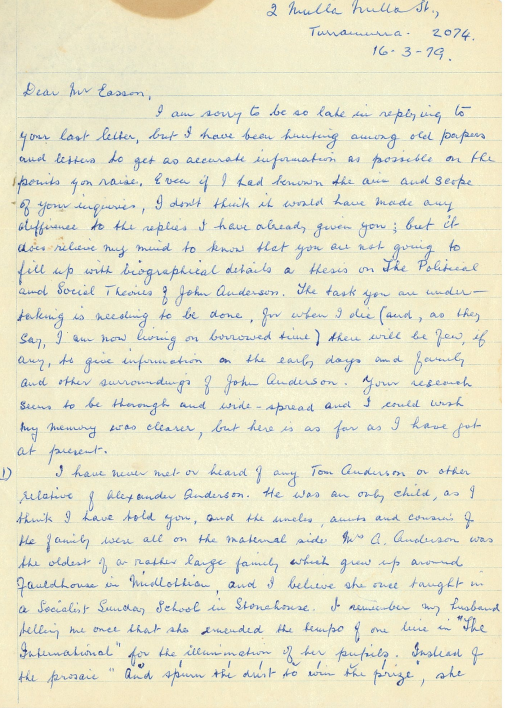

Dear Mr. Easson,

I am sorry to be so late in replying to your last letter, but I have been hunting among old papers and letters to get as accurate information as possible on the points you raise. Even if I had known the aim and scope of your inquiries, I don’t think it would have made any difference to the replies I have already given you; but it does relieve my mind to know that you are not going to fill up with biographical details a thesis on The Political and Social Theories of John Anderson. The task you are undertaking is needing to be done. For when I die (and, as they say, I am now living on borrowed time) there will be few, if any, to give information on the early days and family and other surroundings of John Anderson. Your research seems to be thorough and wide-spread and I could wish my memory was clearer, but here is as far as I have got at present.

(1) I have never met or heard of any Tom Anderson or other relative of Alexander Anderson. He was an only child, as I think I have told you, and the uncles, aunts and cousins of the family were all on the maternal side. Mrs A. Anderson was the oldest of a rather large family which grew up around Fauldhouse in Midlothian, and I believe she once taught in a Socialist Sunday School in Stonehouse. I remember my husband telling me once that she emended the tempo of one line in “The International” for the illumination of her pupils. Instead of the prosaic “And spurn the dust to win the prize”, she introduced a livier rhythm “And spurn the dust to win the prize”. I hope this is clear to you. It does make a difference.

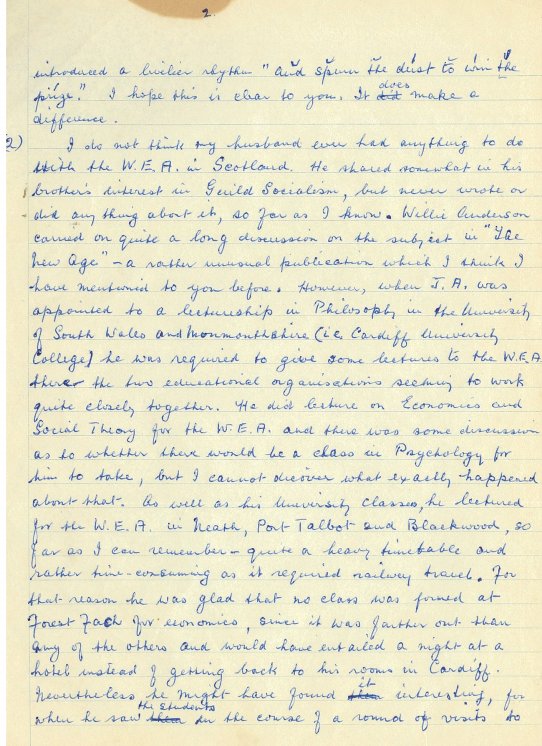

(2) I do not think my husband ever had anything to do with the W.E.A. in Scotland. He shared somewhat in his brother’s interest in Guild Socialism, but never wrote or did anything about it, so far as I know. Willie Anderson carried on quite a long discussion on the subject in The New Age – a rather unusual publication which I think I have mentioned to you before. However, when J.A. was appointed to a lectureship in Philosophy in the University of South Wales and Monmouthshire (i.e., Cardiff University College) he was required to give some lectures to the W.E.A. there – the two educational organisations seeking to work quite closely together. He did lecture on Economics and Social Theory for the W.E.A. and there was some discussion as to whether there would be a class in Psychology for him to take, but I cannot discover what exactly happened about that. As well as his University classes, he lectured for the W.E.A. in Neath, Port Talbot and Blackwood, so far as I can remember – quite a heavy timetable and rather time-consuming as it required railway travel. For that reason he was glad that no class was formed at Fforest-Fach for economics, since it was farther out than any of the others and would have entailed a night at a hotel instead of getting back to his rooms at Cardiff. Nevertheless he might have found it interesting, for when he saw the students in the course of a round of visits to all the work of the W.E.A., he thought they looked bright intelligent, and, incidentally, there were many Communists among them. He seemed to be quite impressed by the work of the W.E.A., and remarked that he must bring it to the notice of his father to see if anything could be done about working with the organisations in Lanarkshire. I don’t know that his father did anything about it: I expect he was busy enough being a schoolmaster, being prominent in the Teachers’ Federation, and lecturing at weekends on Socialism. And I don’t think J.A. did anything about it either when he returned from Wales to a lectureship in Edinburgh. I can find few definite dates, but I think J.A. must have been in Wales from the middle of 1917 to the middle of 1919. At any rate, he was back in Edinburgh for some little time before we were married in the middle of 1922.

(It might be of help to you to know that Hector Hetherington was head of the Philosophy Dept. in Cardiff College at that time. Later he was made Vice-Chancellor, I think, of Glasgow University, a position he held until he died, having collected a knighthood on the way. Possibly H.H. was Lord Rector of Glasgow U.).

(3) Yes. I am the culprit! I did attack Calverton in that article of 1st Feb. 1928, and, by the way I must thank you very much for the copy of it that you sent on. I haven’t seen for many a day that issue of The Communist in which it appears: and I don’t think I would change it much after all these years; though after seeing an amateur performance of A Midsummer’s Night Dream in Newcastle some years ago, I have a better appreciation of the comedy of the four wandering lovers than I had in 1928. Anything else, under the name of J.C. Baillie, would in all probability be written by my husband. I think he used pseudonyms in writing for Communist publications, not so much to conceal his identity as to give readers a chance to appreciate the article or articles objectively, and not because they were written by a particular person. But he was also fond of “playing” with words. Everyone was puzzled by A. Spencer, but it was my son who suggested, in later years, that in the big London Emporium of Marks and Spencer, A. Spencer came after Marx – a very likely explanation of the signature, and one similar to that of “Vera Bacon”, under which pseudonym (at J.A.’s suggestion) I wrote “Friendship with Jesus” for The Communist of Oct. 1928. That, of course, I would re-write completely. I was not comfortable in the writing of it, but now it smacks far too much of the tract, or of propaganda, to please me. Again it was my son who reminded me – if ever I had known – that the name must have its origin in one of Hugh Lofting’s children’s poems:-

“Oh, what a wonderful person I am!

My full name is Vera Virginia Ham.”

Perhaps because of the element of satire or irony in both pseudonyms, J.A. kept silence as to their origin.

(4) Well, well! “Oh what a tangled web we weave, When first we practise to deceive!” Are you sure you have the right date? It just so happens that 1938 was the first of only two Sabbatical Years that John Anderson took all the time he held the Chair of Philosophy in Sydney University. I cannot give you the exact dates, but we left Sydney in the good, old Jervis Bay early in January 1938, and returned at the end of December of the same year in the Monterey. (The Maritime Services Board would surely have the exact dates if you require them). My husband never went to Port Kembla either in 1938 or any other time, and if any other evidence is required to prove the unlikelihood of his ever going – or being “sent”! – to Port Kembla to collect information on ship-building and industry, anyone who knew him at all well would laugh at the idea, for no man on this earth cared less about gadgets and machinery than he. He never went to Port Kembla, and the same pipe dream must be the origin of his correspondence with Trotsky. J.A. never wrote to Trotsky, nor Trotsky to him.

I hope this is of some use to you. If, when I am tidying away the letters and papers, I come upon anything further, especially in connection with the period of his lectureships I shall let you know, and if you require any more information on that or any other aspect of J.A.’s life, I shall do the best I can for you.

Good luck and with best wishes,

J.C. Anderson

MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson, 24.6.79

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

Once again thank you for the assistance that you have provided for my research.

I am hoping, since they are not in the Anderson Archives, that you may be able to track down two lectures that Professor Anderson gave in 1929 to the Australasian Association of Psychology and Philosophy.

(1) The Union Recorder of May 23rd 1929 states that Professor Anderson would deliver on May 25th 1929 a lecture to the seventh Annual General Meeting of the A.A.P.P. on “Philosophy as Freethought”.

(2) The Union Recorder of July 18th 1929 states that Professor Anderson would deliver on August 8th 1929 to a meeting of the A.A.P.P. a paper on “the Philosophy of Lenin”.

I would be most grateful if you could let me know whether these papers have survived and if they could be made available to me.

Looking forward to your reply,

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 29.6.79

Dear Mr. Easson,

I am sorry to say that, at the present moment, I have no knowledge of either of the lectures you mention. They must be among the first that he ever gave, and it’s a long time ago now. I have looked up the Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy round about the relevant period, but there are no signs of them. “Philosophy as Freethought” might have been written up for the Freethought magazine, but I cannot lay my hands on any of the few issues that were published of that journal. My husband spoke always from notes & penciled notes at that, so that if the lectures were never prepared for publication and if they still exist in notes, they will be almost indecipherable now. Still, I’ll keep the matter in mind, and inquire wherever I can, though most of the early students are far scattered and some are dead.

You may have seen in last Saturday’s Herald (23-6-79) the notice of a meeting under the auspices of the Sydney Philosophy Club and the W.E.A., called “the John Anderson Memorial Lecture”. It was delivered on Wednesday of this week by A.J. Baker, B.A., B. Phil., who is a lecturer at Macquarie University, and hopes to have a book published late in August on The Social and Political Philosophy of John Anderson – which was also the title of his lecture. He was not a very early student of my husband, but he was a power among “The Libertarians”, and might just have the information you require.

30-6-79

I am enclosing a Photostat of cuttings which appeared in consecutive issues of the local paper – The Stonehouse/Larkhall Gazette, in April 1973. I had forgotten all about them, but suddenly came upon them when I was clearing away some of the material I had hauled out in connection with your last request. They are not on J.A. himself, but they are interesting in themselves even if they may not come within the scope of your thesis. J.A. was born the year after the Andersons moved from Port Logan in Wigtownshire to Stonehouse, and provide some background from his birth until his University days. The Photostat is unfortunately in very small type, but it was the best my son could get hold of at the time, and it is fairly easily read. I am sending one to the archives so that this will save you a trip thither. I might add, if I haven’t already told you, that Larkhall was the village in which I was born and brought up, about 3½ miles north of Stonehouse and even at that time, more industrialised.

With all good wishes,

J.C. Anderson

MBE to Mrs. J.C. Anderson, 1.2.80

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

I am sorry to pester you with some more questions about John Anderson. These questions, which are largely of a biographical nature, I list in consecutive order:-

a) From what University, and in what Faculty, did Alexander Anderson graduate as a M.A.?

b) In a letter you wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald in response to Professor Boyce Gibson’s review of Studies in Empirical Philosophy you state, “my husband was ‘born a little Liberal’ as Gilbert puts it. But in his teens he became immersed in the socialist theories that were then being hotly debated everywhere…” Does this imply that Alexander Anderson’s politics were Liberal or “radical Liberal” before his conversion to Marxism?

c) Was John Anderson a member of the National Guilds League (which was formed in 1915 and was very strong in Glasgow)? S.G. Hobson in his book Guild Principles in War and Peace refers to William Anderson as a member of the National Guilds League. I wonder whether John Anderson was also active in this League?

d) Whilst domiciled at the University College, South Wales, from 1918-1919, John Anderson was required to give lectures on social and economic matters for the W.E.A. Do you know whether J. Anderson lectured on Guild Socialism?

e) Professor P.H. Partridge in correspondence with me has commented: “Before he came to Sydney, he apparently had a very close intellectual friendship with a man called M.W. Robieson who died very young – he was dead before Anderson came to Sydney, but Anderson often spoke of him”. As an appendix to S.G. Hobson’s National Guilds and the State, is a posthumous essay by Robieson on Guilds and university education. This essay was edited by Robieson’s “literary editor”, W. Anderson. In the New Age journal, Robieson wrote many articles on philosophy, Marxism and Freud’s psychoanalytical theories. Do you know anything about John Anderson’s intellectual friendship with Matthew W. Robieson?

f) Did John Anderson, while at Edinburgh from 1920 to 1926, write for any student, socialist, communist or any other journals?

g) I wonder whether you have any comments on Mr. George Davie’s essay in Quadrant entitled “John Anderson in Scotland” (photocopy enclosed). There seems much in this essay which is elliptical and vague despite the interesting points raised. For example, the reference to The New Age journal is relevant to John Anderson’s intellectual heritage, however the reference to MacDiarmid’s book A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle seems out of place. Further, the reference to the “national culture – conflict” is oblique. What comments do you have about this article?

h) One point raised by Mr. George Davie’s article (at the bottom of page 55 and top of page 57) concerns Norman Kemp-Smith’s plan to take over the W.E.A. in Scotland or, at least, “capture for Edinburgh University the workers’ educational movement”. In view of your comments about John Anderson’s enthusiasm for the work of the W.E.A. while he was lecturing in Wales, was John Anderson associated with Kemp-Smith’s plan?

i) I recently interviewed Mr. Norman Porter who was a tutor in Philosophy at Sydney University from 1929-1932. He told me that in 1927 John Anderson submitted to the Cambridge University Press a book on logic but it was rejected for publication – apparently, according to Porter, by C.D. Broad. Is this recollection by Porter accurate?

j) The reference in your last letter to your article “Friendship with Jesus” for The Communist October 1928, interested me. Unfortunately the October 1928 issue of The Communist is unique in that neither the National Library or Mitchell Library has it. Do you still have a copy of your article?

k) Mr. Judah Waten, the novelist, has written to me about his knowledge of John Anderson in the early 1930s. Waten recalls a meeting with John Anderson in Wellington in 1930 in the editorial office of the New Zealand Communist party newspaper when John Anderson was on his way to visit his brother, William, in Auckland. Can you confirm this? Did John Anderson write for any New Zealand Communist Party journal.

Looking forward to your reply,

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

Mrs. J.C. Anderson to MBE, 4.3.80

Dear Mr. Easson,

I am sorry I have not been able to reply to you sooner, but I have been far from well for the last three months or so. In dealing with the answers to your questions, I hope you will remember that they refer to events of fifty & more years ago, and my memory is not so good as it used to be, so my replies may not be as exact as they might be & must be weighed against whatever information you may have from other sources. That being understood, here goes –

a) Since Alexander Anderson graduated as an M.A., he graduated in Arts, and at the University of Edinburgh, I think. He and his wife were east-country folks, so Edinburgh was the “city” for them, as Glasgow was for us of the west-country. Nevertheless there was a certain amount of interchanging. George Douglas, the author of The House with the Green Shutters and many interesting articles on Literary Criticism, was born & brought up in Ayrshire, yet he studied at E. University. I cannot remember any east-country man who came to Glasgow: after all, Edinburgh was once christened the “Athens of the North”.

b) I’m not quite sure what is meant by a “Radical Liberal.” The term “Radical” has been applied at different times & with different connotations, but if you mean a root and branch Liberal like, for instance, the French Revolutionaries, he certainly was not that, though I don’t know what his opinion of the French Revolution was and I don’t know that he was ever converted to Marxism, as you state. He was from the end of the century known as a Socialist, a S. of the Democratic Party (S.D.P.) as contrasted with a Socialist of the Labour Party (S.L.P.), as I’ve told you before.

c) I do not think that J.A. was ever a member of the National Guilds League. His brother was very active there and carried on a discussion with Hobson for many weeks in The New Age.

d) No, I do not know if J.A. lectured on Guild Socialism when he was in Wales.

e) My impression is that M.W. Robieson was more a friend of William Anderson than of J.A., though J.A. thought a great deal of him & would, I suppose, have seen quite a lot of him in the Glasgow University days. He was dead before I became particularly friendly with J.A., and if my memory is not playing me false, I think he was accidentally drowned while bathing during a holiday in Cornwall.

f) Not so far as I remember. He certainly would not have written to a Communist Journal, because, as I think I mentioned before, he was just finding his way into Communism when we left Scotland in 1927. Neither of us had much time for anything beyond personal matters in these years. Houses were very scarce in those days after the War, and we had some difficulty in getting a suitable dwelling when we married in 1922. We moved twice between 1922 & 1927, our son was born, J.A. was for a time external examiner for St. Andrews University, etc., etc. And though I think he never wrote for the Students’ Magazine in Edinburgh, he was always interested in it. It’s the only magazine that I remember coming into the house at the time – except The Strand Magazine – for The New Age was dead.

g) As regards the article by George Davie in Quadrant I am inclined to agree with you, although I must confess I have not studied it very deeply. I find it both confusing and confused – especially that one long paragraph beginning “Preparing for a dignified surrender…” It is one long involved sentence from beginning to end, difficult to keep hold of and to understand. In a first quick run-through I found myself objecting to the Americanisms – e.g., identify as an intransitive verb instead of a reflexive one, and phrases like “culture-hero” and “culture-conflict”. There is also the short-cut – e.g., Scottish geometry. Now there is no such thing as Scottish geometry, there is only geometry; nor even Scottish education. There is geometry as it is taught in Scotland, and education as it is understood in Scotland. I know that the conception of what education is, has changed in Scotland in the last 50 or 60 years, and I’m not quite sure, but I think in A.A.’s time, the University Arts Degree consisted of 7 subjects which had to be taken by all who aimed at an M.A. degree. The Scottish Universities had no B.A. degree: either an M.A. or an M.A. with Honours in a particular subject). And though I am not so sure of this either, one had to have an M.A. degree before proceeding to Medicine, Science, Divinity, etc. In my day, the M.A. degree still consisted of 7 subjects, each one different, or 6 subjects with a second year in any particular subject, but one of these subjects must be either Logic or Moral Philosophy. It is interesting that both of these classes (first year anyway), the professor prefaced his lecture with a prayer. It may be because they were the first of the day – Moral Philosophy at 8a.m. and Logic at 9 a.m. – but one can imagine at least one other reason. J.A., having taken both classes, could repeat both, even imitating the Welsh accent of Prof. Jones. But I took only Logic, and Prof. Latta’s prayer went something like this: “Almighty God, with whom are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge, enlighten us with the vision of truth, inspire us with the love of wisdom, and enable us to find freedom in our knowledge of thee. Amen”. In Logic we had even a preface to Prof. Latta’s prayer, for as soon as he reached the rostrum, the men at the back of the class room burst into song with “Ye mariners of England”, sung with a great wealth of expression. It all puzzled me at first, but nobody seemed to bother about it, and it was only long after, in Australia, that I read in a book by one of the Brogans, that the author, T. Campbell, had once been a professor of Logic at Glasgow University.

However, I’d better get back to Mr Davie, although I’m afraid I cannot clarify matters at all. Section (f) may explain why I could have been blind & deaf to much of what was going on. But I simply did not know of it or what it all amounted to. Nor did I know of this “masterpiece” of one MacDiarmid, until I saw it mentioned in the article, so that does not help to clarify things either.

h) In view of what I said in the last section, you will understand that I cannot say anything about any plan of Prof. Kemp-Smith, and I cannot remember J.A. ever making any remarks on the subject. I don’t think I meant that J.A. was ever terribly enthusiastic about the work of the W.E.A. In the particular class to which I referred, I think he was disappointed at not getting the opportunity of working with the students who had presented themselves; they seemed so keen and eager. I don’t mean, of course, that he was antagonistic to it (the W.E.A.): he was friendly with the lecturers & helped out with lectures when help was required here in Sydney.

i) I am not very clear about the affair that Norman Porter was relating to you. In January of 1927 we left Scotland for Australia, so the book must have been submitted before 1927. There is such a book on Logic, but if I ever heard to whom it was submitted, I have forgotten. It belongs to the period when I was up to the neck in things domestic.

j) If I had thought you hadn’t come across the article “Friends with Jesus’, I wouldn’t have mentioned it. It’s far too propagandist, somehow; and perhaps it is the reason I stopped writing. But I’ll send you a copy. There’s only one sentence that I can now think of with equanimity, & I’ll mark it.

k) I can’t confirm the various particulars you mention, but I remember that J.A., on the evening of the day we landed in Wellington, went to some Communist Party rooms, still in the search for information about Communism. I don’t think he ever wrote for any N.Z. Communist Party journal.

Sorry the writing has tapered off so badly but I did want to get my reply to you finished tonight.

Postscript (2015)

As published in the Northern Line, Weblin edited the answers to flow under each question.

My interest in writing something original on John Anderson was later subsumed by my writing a Ph.D. on Matthew Robieson, someone J.A. knew and possibly was influenced by. Certainly, Anderson’s bother, William, was a close friend of Robieson.