Article published in the Land Journal, journal of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors [UK], February-March 2013, pp. 22-23.

Port Moresby’s population is still small, although it is growing rapidly. Within 50 years, it is easy to imagine a city of significant size, up from the present 250,000 to one million, or even several millions.

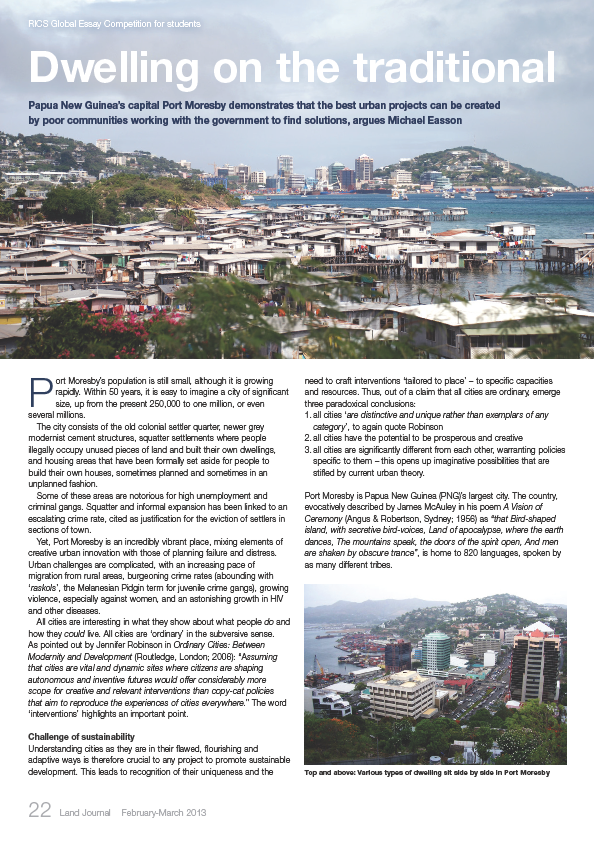

The city consists of the old colonial settler quarter, newer grey modernist cement structures, squatter settlements where people illegally occupy unused pieces of land and built their own dwellings, and housing areas that have been formally set aside for people to build their own houses, sometimes planned and sometimes in an unplanned fashion.

Some of these areas are notorious for high unemployment and criminal gangs. Squatter and informal expansion has been linked to an escalating crime rate, cited as justification for the eviction of settlers in sections of town.

Yet, Port Moresby is an incredibly vibrant place, mixing elements of creative urban innovation with those of planning failure and distress. Urban challenges are complicated, with an increasing pace of migration from rural areas, burgeoning crime rates (abounding with raskols, the Melanesian Pidgin term for juvenile crime gangs), growing violence, especially against women, and an astonishing growth in HIV and other diseases.

All cities are interesting in what they show about what people do and how they could live. All cities are ‘ordinary’ in the subversive sense. As pointed out by Jennifer Robinson in Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development (Routledge, London, 2006):

Assuming that cities are vital and dynamic sites where citizens are shaping autonomous and inventive futures would offer considerably more scope for creative and relevant interventions than copy-cat policies that aim to reproduce the experiences of cities everywhere.

The word ‘interventions’ highlights an important point.

Challenge of Sustainability

Understanding cities as they are in their flawed, flourishing and adaptive ways is therefore crucial to any project to promote sustainable development. This leads to recognition of their uniqueness and the need to craft interventions ‘tailored to place’ – to specific capacities and resources. Thus, out of a claim that all cities are ordinary, emerge three paradoxical conclusions:

1. All cities “are distinctive and unique rather than exemplars of any category”, to again quote Robinson.

2. All cities have the potential to be prosperous and creative.

3. All cities are significantly different from each other, warranting policies specific to them – this opens up imaginative possibilities that are sometimes stifled by current urban theory.

Port Moresby is Papua New Guinea’s (PNG’s) largest city. The country, evocatively described by James McAuley in his poem ‘New Guinea’ (A Vision of Ceremony, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1956) as “that Bird-shaped island, with secretive bird-voices, Land of apocalypse, where the earth dances, the mountains speak, the doors of the spirit open, and men are shaken by obscure trance”, is home to 820 languages, spoken by as many different tribes.

The tribes inhabit 19 provinces, varying in lifestyle, social status, customs, traditions, and, of course, language. The population of 6.5 million lives mostly in rural villages, although migration to Port Moresby, Lae, Rabul, Mandang, and other townships is proceeding apace.

Modernity has arrived, but it would be a mistake to think that this explains much. This is because of the strong kinship of origin and clan manifested in urban life. D. Ryan’s study of Toaripi migrants in Port Moresby (Bilocality and Movement Between Village and Town, 1985) provides information on their settlement patterns at Vabukori, with the major focus on rural-urban links. Before European settlement in the 19th century, tribes lived in isolated villages separated by mountains and rainforests. After the arrival of the British, Australians, and Germans, urban centres were established within the villages (today known as ‘urban villages’).

Port Moresby’s dynamism offers perspective and insight on the task of sustainable development. Many Motuans (native PNG inhabitants) live in houses built on stilts in coastal areas such as Hanuabada. Originally, these houses were built from wood and thatch, but most were destroyed by fire during World War II and they are now constructed from corrugated iron and wood. They can last for 20 to 30 years, depending on the timber used, with stilts up to 4m high to allow for high tides and strong winds. Some have plumbing and electricity.

Port Moresby characteristically consists of various conurbations including villages within urbanised areas. Houses are often haphazardly arranged or in clusters, and living conditions vary greatly. There are some well-built houses of concrete, timber and corrugated iron with basic services, while others are poorly built, makeshift houses of sub-standard materials, scrap metal and plywood, with no basic services.

Urban villages are mainly identified by tribes who speak the same language, but they may also be home to several tribes. For example, Hanuabada Urban Village is dominated by two groupings with distinct lifestyles — the Motu and Koita people.

The Motu live in compact villages at the edge of the sea, while the Koita live in scattered villages built on ridges that run parallel to the coast and are grouped around a central space.

Kila Kila Village (originally a Koita village) is another urban village in the city, with a large migrant population that has permission from the landowners to live there in exchange for some form of payment. Migrants bring with them their distinct lifestyles, customs and traditions, and conflicts are not uncommon. The positions and the arrangements of houses may also vary as a consequence.

From the outside, it might seem fractured and fragile. John Connell, in noting growing urbanisation in the islands of the Pacific, including PNG (‘Elephants in the Pacific? Pacific Urbanisation and its Discontents’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 2011), associated this with civil unrest, unemployment, crime, poverty, environmental degradation, traffic congestion, inadequate formal housing provision, the rise of the informal sector (and repressions of it), and pressures on education, housing, health and other services, rather than with sustained economic growth.

Recognition of the Traditional

But that is to miss some detail. Much ripples from under the surface. Systematic observation and measurement require supplementation. To be significant, knowledge usually requires theorising, or calls on theory for perspective. In Port Moresby, there is the everyday social environment of migrant settlers and urban villagers who daily negotiate the legacies of tradition and the colonial past, and the contemporary challenges of modern city life.

Turning more directly to the challenges of sustainability, globalisation has come to mean that new technology threatens cultural and design origins, with an overwhelming influence of the ‘imprinting’ carried out by larger, developed societies on their smaller, less developed hosts.

Recognition of the importance and sustenance provided by traditional design and craft has led some PNG policy-makers and architects to take seriously the country’s culture, climate, history, materials, human resources and economy as it evolves and focus on finding solutions that realistically reflect the financial, cultural and physical needs of local people. In resisting the temptation to simply import solutions, there is a body of work drawing from traditional building methods and materials and exploring design solutions that reflect an understanding of local cultural priorities.

Postscript (2015)

I first went to PNG in the early 1980s. This was connected with my involvement with the Labor Committee for Pacific Affairs, about which I have written elsewhere – cf. ‘Labor and the Left in the Pacific’ (1989).

A number of union leaders I met, including Napoleon Liosi, Henry Moses, and Lawrence Titimur – from the far flung parts of the country.

I read widely and found the disparate, complex nation of great fascination. Because of an intellectual interest in James McAuley (the poet) and Ross Garnaut (the economist), their publications and interests related to PNG, I was curious about.

In my MSc in sustainable urban development course, one of the essay topics was to pick a ‘global south’ city to write about. I wrote on Port Moresby. I adapted my essay for publication in the RICS journal.