Article published in Workplace Review, Thompson-Reuters publishers, July/August 2020.

Jack Mundey: 17 October 1929 – 10 May 2020

John Bernard “Jack” Mundey (1929-2000), conservationist, union leader, activist, was an unlikely hero. This article briefly summarises his life, achievements and, finally, reflects on lessons from a life that endured more disappointments than triumphs.

Born just after the Wall Street crash into rural poverty in Malanda in the Atherton Tablelands, west of Cairns, more than a thousand and a half kilometres from Brisbane, he lost his mother early (she was 42 and he was one of 5 children). His formal education finished before the Leaving Certificate, and a promising rugby league career beckoned. In 1952 he moved to Sydney and played in Parramatta’s reserve grade. Working in various unskilled jobs, and as a labourer, he became a militant, joining the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) in 1957, a difficult year for a budding, ‘humanist’ communist.

In 1995, NSW premier Bob Carr appointed him chair of the NSW Historic Houses Trust; he served 7 years becoming patron in 2002. Mundey was a member of the council of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF), and from 1984-1987 he was a councillor of the City of Sydney. In 1997, the National Trust named him a National Living Treasure. In 2000, on the nomination of the NSW government, Mundey was made an officer in the Order of Australia (AO) for service to the identification and preservation of significant sections of Australia’s natural and urban heritage through initiating “green bans”. In 2011, he was elected president of Australians for Sustainable Development. He received honorary doctorates in Science (University of NSW) and Letters (Western Sydney University).

What happened in between unpromising beginnings and public lauding was a journey – becoming Australia’s best-known conservationist and, after Bob Hawke, Australia’s most famous unionist.

From debates and discussions with comrades and friends he grew, particularly after 1965 when he married Judith Willcocks, one of the pioneers of the Australian women’s liberation movement in the 1960s. As Judith Mundey, she stood as a communist candidate in the 1967 and 1968 NSW state elections and in the 1980 Federal election. She was the first woman national president of the CPA, 1979-82. Earlier, she was secretary of the CPA Sydney district committee, 1973-79.

Mundey honed his skills in negotiation, organisation, and agitation as an organiser from 1962 in the NSW Branch of the Builders’ Labourers’ Federation (BLF), a poorly organised union covering unskilled labour in the building industry. In 1968 Mundey was elected NSW secretary of the union. Along with his mates Joe Owens (1935-2012; NSW BLF Secretary, 1973-1975) and Bob Pringle (1942-1996; NSW BLF President in the late 1960s) they transformed the industry. No one could describe any one of them as gentle souls.

Moderate, pally with bosses, cutting deals over a swanky meal at the Beefsteak and Bourbon at Kings Cross, were descriptions never applied to the militant trio. The industry was a tough maelstrom of what you could get away with. With relish, through strike action and aggressive tactics, they galvanised support from the membership for higher wages, better health and safety, and civilised treatment of the workforce. In 1970, a 5-week building strike in support of better conditions, created enemies among employers, the conservative Askin-led NSW government, and other unions.

In 1970, Mundey was approached by community representatives, mostly middle-class housewives exasperated by cold-shoulder receptions by local politicians indifferent to their concerns about the destruction of Kelly’s Bush, 12 acres of bushland along the Parramatta River in Hunter’s Hill. In a buoyant time for the building industry, Mundey saw merit in their campaign and coined the term “green ban” to describe the union’s 1971 decision to ban demolition or building work in the area. To “persuade” the developer of the merit of the BLF decision, Mundey threatened another of its major projects in North Sydney. He forced abandonment of plans to clear the mostly pristine, natural shrubbery.

From there began the green bans movement. Sometimes in industrial disputes, unions would declare a job “black”, hence the expression “black ban”. The BLF extended this concept to the natural and built environment, which led to green bans.

After Kelly’s Bush, came requests for assistance from other community groups. Over 54 green bans were declared. The most famous were the Rocks, the one square mile beginning at the foot of the Sydney Harbour Bridge on the western side of Sydney Cove where Australia was first settled; Victoria Street, an historic and gracious avenue on the lip of the King’s Cross escarpment; Woolloomooloo; Centennial Park; and a natural bushland gully in Randwick.

The Lord Mayor of Sydney, David Griffin (1915-2004; Mayor, 1972-1973; knighted, 1974) furiously condemned the BLF’s opposition to “progress”.

A lemon-soured, pursed lips editorial writer in The Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1970s conveyed conventional opinion: “There is something highly comical in the spectacle of builders’ labourers, whose ideas on industrial relations do not rise above strikes, violence, intimidation and the destruction of property, setting themselves as arbiters of taste and protectors of our national heritage.”

Mundey did not care for the putdown of the hard-hat BLF aesthetes and their community friends. In a profile in The Bulletin magazine in 1973 he said: “What is the use of winning a 35-hour week if we’re going to choke to death in plan-less and polluted cities, devoid of parks and denuded of trees? What’s the use of winning that?”

In a 1977 interview, he commented: “The worker hits the factory of a morning, performs certain work for a number of hours; then he goes out and ignores the fact that the environment in cities is being destroyed, that the transportation systems are terrible.”

These were the articulate stirrings of a “green”, pro-environment philosophy.

Mundey’s efforts inspired Neville Wran (1926-2014; Premier of NSW, 1976-1986) to pass the Heritage Act 1977 and the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979.

By the mid-1970s, Mundey was effective in his broadening of “union business” to include the environment. He campaigned for wage justice and dramatic improvements in health and safety in a tough industry. Mundey urged “progressive” developers and the authorities to consider the “social” in conception and approvals of projects. An example of the latter was the incorporation of a new Theatre Royal in the construction of the MLC Centre bordering Martin Place, Castlereagh, and King streets. Even though they had numerous disagreements, Dick Dusseldorp, the founder of Lend Lease (and builder of the MLC Centre), came to admire the principles underpinning Mundey’s thinking.

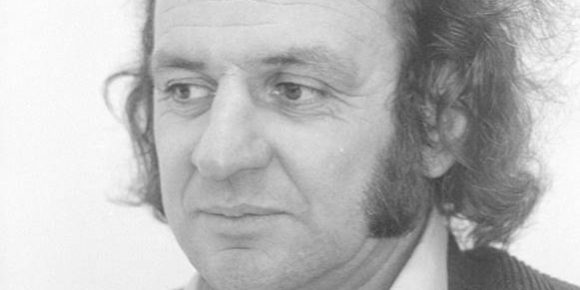

In the early 1970s, Mundey was everywhere, on television and radio, profiled in magazines across the land. Standing with microphone in hand, looking like one of the Chieftains before a performance, his bushy sideburns were one of the distinctive, Sydney eyesores of the era.

When Mundey led the BLF in NSW the national and Victorian offices of the union were run by Maoist-aligned communists. The main rival union, covering carpenters and skilled trades in the building industry, the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU), was mostly under the control of pro-Moscow communists. The Plumbers were militant too, sympathetic to the national office of the BLF, with the Federated Engine Drivers’ and Firemen’s Association of Australasia (FEDFA) another pro-CPA outpost, in sympathy with Mundey. Other, smaller unions, mostly right-wing Labor aligned, covering plasterers and others, tried to keep out of the way.

Mundey’s party, the CPA, from the mid-1960s evolved into a counter-cultural leftist party, independent of Moscow, with more in common with the Eurocommunist Italian Communist Party than any other. In 1968 the CPA voted to condemn the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1969 Mundey visited the USSR and noted the absence of democracy, either at the grass roots or in free elections more generally. In a profile in the early 1970s, Mundey proffered: “I believe in the independent socialist approach and genuflect at the altar of neither Russia or China.”

Hostility to apartheid, opposition to US foreign policy (the New Left in the West were always ultra-critical of Washington), demonstrations to ban nuclear weapons (with degrees of hypocrisy in the pro-Soviet or pro-Beijing wings of the movement), broadly united the far left. The conservative, if nominally “communist” men in the rival unions, however, hated what they saw as Mundey-CPA trendy activism in support of women’s liberation and LGBT rights.

Mundey’s demise as a full-time union official invites a glimpse into the world of Communist Party rivalry. He believed in 5-year fixed terms and relinquished his role to Owens in 1973. Mundey returned to work as a builders’ labourer, working at Sydney Hospital, and became an honorary consultant to the Total Environment Centre.

Mundey, Owens, and Pringle, however, were all expelled from the BLF when the national office of the union led by Norm Gallagher (1931-1999; Victorian and national BLF secretary, 1970-1988) took over the NSW branch in 1975.

Mundey was kept out of employment in the industry. Owens and Pringle survived as dogmen and as members of the FEDFA. (A dogman is a hoist or crane operator on a building site in charge of moving a load, including when the load is out of the operator’s view.)

The National Secretary of the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA) Laurie Short (1915-2014; National FIA secretary, 1949-1982) was one Labor right-winger who spoke up against the outrageous action of Gallagher to prevent his enemies gaining employment in the industry. To do so, Gallagher ruthlessly exploited the ‘no ticket, no start’ rule. Short, himself a survivor of Stalinist bullying when the communists ruled the FIA, met Mundey various times. They came from very different political outlooks, but saw each other as principled, courageous, practical dreamers.

In the 1970s Mundey stood out along with Milo Dunphy (1928-1996) and Geoff Mosley of the Australian Conservation Foundation, and others, to awaken tens of thousands to join and become active in environment organisations and campaigns. To varying degrees, Mundey’s influence eventually permeated into all mainstream political parties, the ALP, the Liberals, and of course the Greens (which he joined in 2003). In combination, he and other figures energised civil society and freshly stimulated a conservationist ethic.

Mundy’s actions showed a path for others to follow. In the early 1990s, a youthful organiser (later NSW secretary) of the BWIU, Andrew Ferguson, worked with the then secretary of the Labor Council of NSW (me) to prevent the demolition of the Finger Wharf at Woolloomooloo. The City Recital Hall in Sydney (opened in October 1999), the first purpose-built music venue to be established in Sydney since the Sydney Opera House in 1973, was forced on the AMP, the owner-developer, by the Sydney Lord Mayor Frank Sartor as a condition of approval. Those actions traced footsteps which Mundey first trod.

Mundey’s battles were rarely a matter of gently persuading or contesting opinion. When in the early 1970s the demolition of the Rocks began, using non-union (scab) labour, residents were summarily evicted from their homes. Members of a tightknit community with BLF members, including Mundey and Owens, occupied sites. NSW Police were sent to “restore order”; in one day 58 activists, Mundey and his BLF comrades included, were arrested. The resultant publicity galvanised opposition; wholescale redevelopment was stopped. The Sirius building was built by the Housing Commission of NSW to house many displaced residents, with the Sydney Cove Authority directed by the minister to support a stronger commitment to heritage.

In the long, second half of his life, Mundey played the role of environmental preacher and advocate, animating many into activism. He ran a few times unsuccessfully for the Senate as a CPA candidate in NSW in the 1970s. He liked to think of himself as a stirrer, a bit of a larrikin, an independent Marxist, unseduced by the establishment.

Initially through Owens, I met Mundey many times. Catching the train to town from Strathfield, I would sometimes meet him at the Ashfield stop on our journeys. Mary, my wife, who won Labor preselection for the Federal seat of Lowe in 1990, winning election on the second attempt in 1993 for a single term, also caught up with him at his apartment at Croydon Park where he and Judy lived. As a prominent local in the area, we were interested in his advice. By then he was a famous figure, and we came to pay respects, ask for contacts and insights. Mundey was intrigued that two ALP right-wingers thought highly of him.

Mundey’s life illustrates several timeless dilemmas in political engagement.

The first is the dilemma of dirty hands: that sometimes to do right you need to do wrong, break the law, in order to achieve a superior goal. Mundey, I think, answered that dilemma correctly: to see no contradiction, to regard the law as flawed, unworthy of moral support. From this perspective no dirty hands were involved.

The other argument is that it is an impossible requirement to expect ordinary souls to be heroes. The hero dilemma is this: If a person is expected to be or needs to be a hero that is a flaw in the moral order, which ought to be changed. With respect to the environment, Mundey was a catalyst to that end.

One might say, generally, without delving too deeply into the technical refinements, that Mundey’s life illustrated the contrast between Kantian and Humean ideas of morality.

Immanuel Kant’s “categorical imperative” is the unconditional moral principle that a person’s behaviour should accord with universalisable maxims which respect persons as ends in themselves; the obligation to do one’s duty for its own sake and not in pursuit of further ends. Although our moral lives are preoccupied with the question of how to be virtuous over the course of a life, Kant defines virtue in terms of the more fundamental concepts of law, obligation, and duty. For Kant obligation is at the very heart of morality, whereas for David Hume it is not. Kant believes that our moral concerns are dominated by the question of what duties are imposed on us by a law that commands with a uniquely moral necessity. For Hume, such concepts are far less central and differently considered. For Hume, the broader and somewhat looser notion of “personal merit” lies at the heart of morality. On this reading, our moral concerns are dominated by the question of which motives are virtuous. To answer this question requires looking to the responses of our fellow human beings, who approve of those motives and character traits that are useful or immediately agreeable. Those are the terms that characterise duty and obligation for Hume, rather than the other way around.

Although he would not use this language, Mundey sought to Kantinise the law, creating binding obligations to respect the environment. But in the meantime, the Humean ideal of doing what pleased the good people he knew, would do.

Coming from the rainforests of North Queensland to the concrete jungle explains some of the visceral reaction and counter-reaction in Mundey’s life. While controversial at the time, he helped spawn a movement that contested the narrative that change equals progress; he decisively saved streetscapes, housing, heritage buildings, natural conservation areas, and parks in Sydney and beyond. A movement developed from those acts. That is Jack Mundey’s memorable legacy.

Judy, his wife, survives him. A son, Michael, predeceased him in his early twenties in 1982, a passenger-victim of a car accident, as did his first wife, Stephanie née Lennon, who died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage, aged 22.