Published in the National Outlook, March 1982.

After reading B.A. Santamaria’s criticisms of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace’s policy statement on World Disarmament I am more than ever convinced that peace advocates should be careful in their arguments.

I have several comments to make about the discussion in last month’s issue of Outlook, concerning the weaknesses in the CCJP’s position and about certain philosophical questions which need to be aired.

There are a number of points advanced in the CCJP policy which are confused:

(a) The document refers to the “kind of nuclear war for which countries possessing nuclear weapons have prepared themselves” with little elaboration save the comment that “the world’s military powers” desire to make “population centres hostages” to their power plays. This is very simplistic. There are nuclear warheads pointed in the direction of New York and Leningrad which if fired would wipe out millions. But nuclear warfare is likely to be initially fought by destroying armies and military installations rather than cities. The consequences and dangers of escalation including the destruction of “population centres” is not the only possibility of nuclear war.

(b) CCJP claims that the necessary “political will” is lacking in the task of disarming nations. I only wish this were true. In dealing with the Minotaurs of the Gulag Archipelagoes in the Soviet Union and China I do not believe that smiles and expressions of peace or unilateral steps of disarmament will convince them to beat their nuclear weapons into solar-powered ploughshares. In dealing with these regimes it is not enough to be brimful of good intentions.

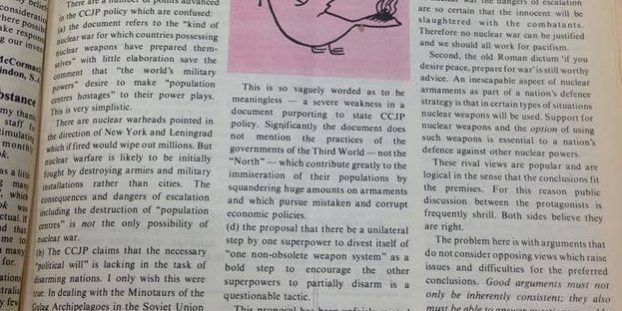

(c) “World poverty” is rightly referred to as being worsened by massive expenditures on armaments but the document does not stop there. The claim is: “The basic reason why people go without food, shelter, housing, education and work is because of a complex of economic and political systems reaching beyond national borders, which effectively exclude the majority of the world’s population from participating in their own development…” This is so vaguely worded as to be meaningless – a severe weakness in a document purporting to state CCJP policy. Significantly the document does not mention the practices of the governments of the Third World – not the “North” – which contribute greatly to the immiseration of their populations by squandering huge amounts on armaments and which pursue mistaken and corrupt economic practices.

(d) The proposal that there be a unilateral step by one superpower to divest itself of “one non-obsolete weapon system” as a bold step to encourage the other superpowers to partially disarm is a questionable tactic. This proposal has been unfairly quoted as a call for unilateral disarmament. My difficulty rests on whether this is a tactic likely to succeed. In 1977 President Carter offered a massive reduction in nuclear arms; late last year President Reagan offered a halt in the nuclear re-arming of Europe. Both offers were spurned by the Soviet Union. The issue of “what is the necessary unilateral step that will be convincing to the Soviet Union” needs to be discussed – not glossed over.

Finally a comment on why there is usually only the ‘appearance’ of argument in discussions of this kind.

One of my problems in following the views of the most articulate protagonists in the world disarmament debate is that, impeccably, their conclusions follow from their premises.

Let me summarise two rival positions.

First, a just war is one where the good to be achieved outweighs the evils of warfare and where clear distinctions can be made between the innocent and the combatants. In nuclear war, the dangers of escalation are so certain that the innocent will be slaughtered with the combatants. Therefore no nuclear war can be justified and we should all work for pacifism.

Second, the old Roman dictum “if you desire peace, prepare for war” is still worthy advice. An inescapable aspect of nuclear armaments as part of a nation’s defence strategy is that in certain types of situations nuclear weapons will be used. Support for nuclear weapons and the option of using such weapons is essential to a nation’s defence against other nuclear powers.

These rival views are popular and are logical in the sense that the conclusions fit the premises. For this reason public discussion between the protagonists is frequently shrill. Both sides believe they are right.

The problem here is with arguments that do not consider those opposing views which raise issues and difficulties for the preferred conclusions. Good arguments must not only be inherently consistent; they also must be able to answer questions posed by competing arguments.

I am conscious that I am here stirring philosophical waters too deep to plunge into in this short review. But I believe that besides highlighting the obscure in the CCJP’s position, it should be pointed out that the world disarmament ‘debate’ rarely qualifies as a genuine argument.

Postscript (2015)

A friend from university student days, Warwick Grundy, became the editor of this little ecumenical Christian journal – I think for a year or two. He asked me to submit something on ‘Peace’ – and I decided to write on the latest promulgation by the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP). As this article makes clear, their arguments in their pamphlet World Disarmament were too cocksure and without empathy for alternative perspectives within a Christian tradition. I thought the authors and the grouping around the CCJP would eventually be disowned by the Church.

It is damn difficult to express Christian ideals on important contemporary questions and be effective in the public square. Always, though, it is handy to at least try to intelligently appreciate alternative perspectives. Stridency without empathy is a sure way to lose support.

Greg Sheridan wrote an article which referenced my article in an overview of efforts by the ‘peace movement’ to win support in the unions and the churches in favour of disarmament. (See: Greg Sheridan, Peace Coalition Gathers Pace, The Bulletin, Vol. 102, No. 5317, 8 June 1982, pp. 41-42; 45-46.)