Review by Michael Easson of Michele Alacevich, Albert O. Hirschman. An Intellectual Biography, Columbia University Press, New York, 2021, published in Tocsin, journal of the John Curtin Research Centre, Issue 16, July 2022, Melbourne, Australia, https://www.curtinrc.org/the-tocsin-issue-16/#the-hirschman-difference.

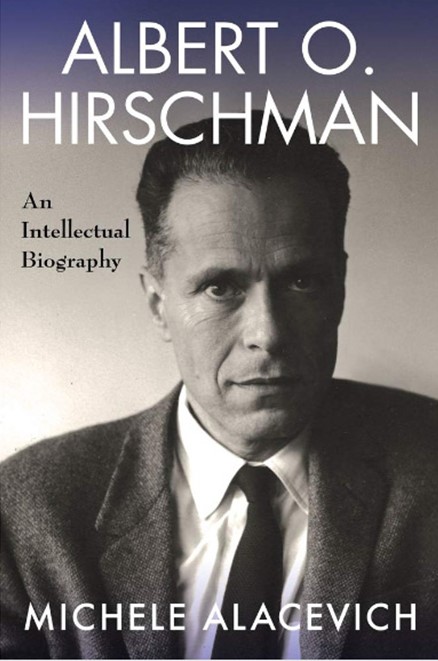

Rare is the book that with verve, clarity, enthusiasm, and authority establishes the claim that a thinker demands reappraisal and even celebration. Alacevich’s book finely interprets one of the great social theorists of the twentieth century, Albert Hirschman (1915-2012), economist, sociologist, political philosopher, development economics theorist, social democrat reformer, and iconoclast, forever discussed as one of the could-have-been-but-was-not-to-be Nobel Prize winners in Economics. Alacevich beautifully compliments Jeremy Adelman’s biography, Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey Albert O. Hirschman (2013) in explaining why this individual deserves to be better known.

What an extraordinary life: In mid-January 1941, the émigré Hirschman stepped onto American soil in New York for the first time, aged 25. He could fluently speak five languages (German, French, Italian, English, and Spanish). Born during the Great War, growing up in Weimar Germany, he came from an assimilated Jewish family, baptised Lutheran, son of a prosperous medical specialist, in a family economically ruined by the Great Depression, then tormented by rising antisemitism. At senior high school in Berlin, he organised demonstrations against the Nazis. As Jews and those of Jewish heritage were expelled from German universities in April 1933 (a month after his father died), he left Berlin for France, only returning to Germany again 46 years later. In Paris he studied at the École des hautes études commerciales de Paris specialising in economic geography.

After graduating he spent a year at the London School of Economics (LSE) refining his knowledge of economics. On returning to Paris, he joined the international brigades in Catalonia. Injured, he moved to Trieste in Italy to commence doctoral studies and to spend time with his sister Ursula (1913-1991) and her husband, Eugenio Colorni (1909-1944), the Italian economist, political philosopher, and anti-fascist activist who was arrested and murdered by Nazi thugs shortly before the Allies liberated Rome.

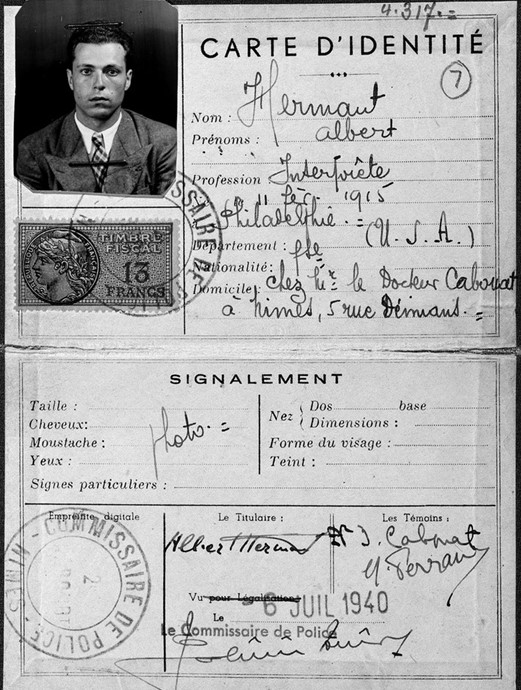

In Vichy France, from the port of Marseilles, in 1940 Hirschman worked as second-in-command to Varian Fry, the American journalist, who through the Emergency Rescue Committee saved the lives of thousands of intellectuals and others who would have been murdered by the Gestapo or left to perish in the camps. Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Golo and Heinrich Mann, Arthur Koestler, Hannah Arendt, were some he helped save. This activity only came to be better known late in Hirschman’s life. Queried about why he had not spoken about this earlier, he felt saddened that he had not saved more, names of people the world would never hear. Himself hunted, arrested, false identification papers and lack of tight incarceration gave Hirschman opportunity to escape. In December 1940 he fled France for the US.

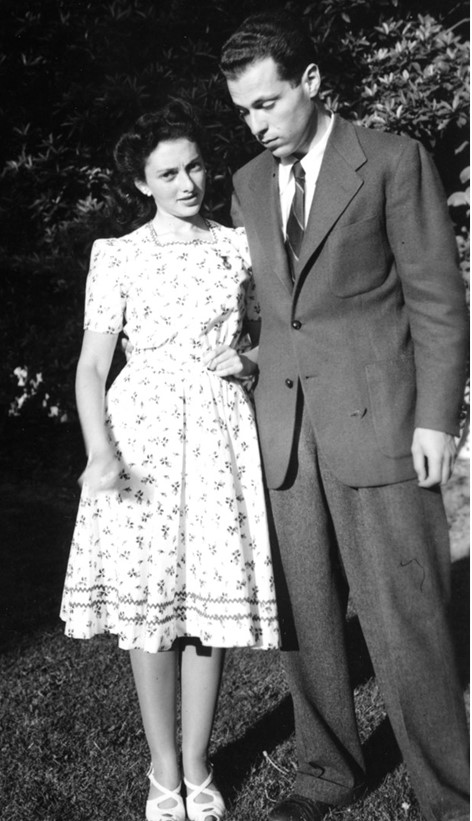

Beforehand, the New Zealand born economist Professor John B. Condliffe (1891-1981) was important in promoting and cultivating opportunities for Hirschman as he initially worked on trade policy and Italian population statistics. Condliffe was impressed by his productive intuitions. First in Europe in 1937 for the Economic Intelligence Service of the League of Nations, later at the LSE in the same year, then in 1940 Hirschman was invited to join Condliffe at the University of California at Berkeley. Through Condliffe, Hirschman engaged with an interesting milieu of intellectuals. He met and married Sarah Shapiro in California in 1941. He briefly worked for the Federal Reserve Board. Thereafter began a long career in academia at leading American universities and as a public intellectual. Development economics became an abiding interest. In 1996 a severe hiking accident in the Alps led to noticeable decline; he died 16-years later.

Hirschman privileged doubt and curiosity over the ideological certainties he encountered in an epoch captivated and manipulated by communists and Nazis. He realised that morality can never be expunged from the social sciences. He drew insight from Marx’s writings, his uncanny mix of ‘cold’ scientific propositions and ‘hot’ moral outrage “with all of its inner tensions unresolved” which explained their appeal. Hirschman was no revolutionary, however. Indeed, he saw revolutionary shortcuts as completely unappealing.

He placed emphasis on the concept of possibilism, his unique contribution to the theory of reformist activism. In the 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard coined the term the “passion for the possible.” Passion is not bloodless. Sometimes reform is impossible unless the reformer is “exhilaratingly conscious of writing an entirely new page of human history.” Alacevich suggests: “For Hirschman, as for Colorni, doubting is not a force conducive to abstraction and paralysis, but rather the foundation for commitment to action.”

In contrast, the revolutionary activist’s expectations are unrealistic as they fail to visualise “intermediate outcomes and halfway houses.” The true visionary act, Hirschman implied, is not to prefigure outright revolution – usually a simplistic and schematic act of imagination – but to conceive the possibility of even modest advancements, and to build political resilience. In Hirschman’s words: “It is the poverty of our imagination that paradoxically produces images of ‘total’ change in lieu of more modest expectations.” Additionally, the cost of more sweeping change can be catastrophic to life and the stable economic foundations of a society.

One witty, optimistic phrase he sometimes deployed to prod those Hirschman knew, urging them to keep up their spirits, to keep hope alive, comes from his book Journeys Towards Progress (1963): “Reformers… behave like the country or the chess player who exasperatingly fights on when ‘objectively’ he has already lost – and occasionally goes on to win.” Daring to win, particularly against expectations, was typical Hirschman bravado.

Hirschman opined: “What is actually required to make progress with the novel problems a society encounters on its road is political entrepreneurship, imagination, patience here, impatience there, and other varieties of virtù and fortuna.” He had in mind Machiavelli’s idea of the virtues needed for the achievement of great things as well as appreciation for the role of good fortune and the opportunist instinct to find it.

Borrowing an expression from Flaubert, La rage de vouloir conclure (“the rage for wanting to conclude”) he saw that some academics and activists want to rush ahead of themselves – to reach a conclusion without properly considering the rich dimensions of the problem to be solved. One might observe that in the same circles there is also La rage vouloir rester dans les annales (“the rage to stay in the annual records”), to be memorable, significant, and, alas, theoretically preening. Profundity-seekers frequently are so.

Problems are usually less malleable than what models predict, however. An unorthodox thinker, as Alacevich explains: “Hirschman was interested in unravelling the mechanisms behind shifting preferences, whereas mainstream economics considers preferences as given.” Hirschman was intensely interested in why those preferences change. Much economic theory and explanations of human behaviour, to Hirschman’s eyes, lacked any historical sense or worldliness. In Hirschman’s words: “…the unfolding of social events… makes prediction exceedingly difficult and contributes to that peculiar open-endedness of history that is the despair of the paradigm-obsessed social scientist.” Not that Hirschman was dismissive of the insights of classical economics. For example, Hirschman “…highlighted that the classical economist considered trade beneficial not so much because humans are inherently peaceful as because it is in the nature of trade to build a web of interrelationships so wide and complex that states become increasingly unable to pursue their power ambitions without deeply damaging their own interests.” In that summation, orthodoxy is expressed with democratic insight.

Alacevich highlights Hirschman’s reformist and social democratic vision, which was never far from view. Hirschman brought an inquiring and sceptical mind to questions of competition. As an example, he contested Schumpeter’s theories of “creative destruction” arguing that with laggard firms “mechanisms of recuperation would play a most useful role in avoiding social losses as well as human hardship.” Social costs, Hirschman understood, could not merely be dismissed, or ignored in the analysis. (Joseph Schumpeter in his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1942, argued that “creative destruction” is how economic progress occurs as firms decline and emerge in circumstances of competition. Some economic libertarians in subsequent decades grew too fond of celebrating the destruction, without caring about the consequences, the human impacts, and potential alternatives, such as repair and revitalisation of a firm.)

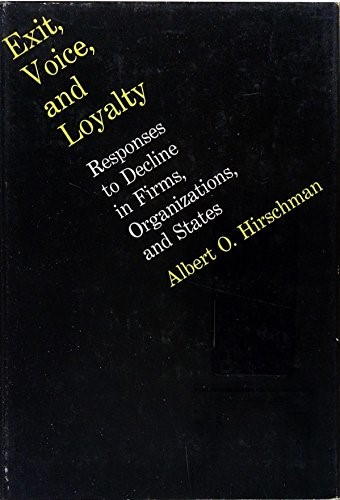

Hirschman was always absorbed in political theorising, synthesising new perspectives, amalgamating ideas in his own eclectic way. His most highly regarded book is Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970); his most scholarly, The Passions and the Interests (1977). Exit was a volume that marked Hirschman’s transformation from political economist to all-round, deeply interdisciplinary social scientist. The work was dedicated to his late brother-in-law, Eugenio Colorni, who joked that his writings were like castelluzzi – “little castles” – a hint of ironic, Cervantean self-doubt.

The second half of 1960s and the 1970s were his intellectually most productive. Hirschman wrote prolifically. Alacevich notes: “…Hirschman was less interested in discovering a topic from all possible perspectives than in picking a particular viewpoint…” He sometimes evinced the reformer’s impatience for getting to a decision.

Hirschman rejected the bland simplicity of the ‘either-or’ mindset and argued for careful project appraisal: He protested: “Why should all Latin America find itself constantly impaled on the horns of some fateful or inescapable dilemma?” He answered: “Any theory or model or paradigm propounding that there are only two possibilities – disaster or one particular road to salvation – should be prima facie suspect. After all, there is, at least temporarily, such a place as purgatory!” What should replace such analysis? Hirschman thought he had a solution.

The triad of exit, voice, and loyalty had a wide ambit. As Hirschman wrote in his introduction the goal was to propose a “unifying way of looking at issues as diverse as competition and the two-party system, divorce and the American character, black power and the failure of ‘unhappy’ top officials to resign over Vietnam.” As Alacevich dryly notes, the project did not lack for ambition.

By using the concepts of exit and voice, his goal was to overcome the “fundamental schism” between economics and politics. The terms are worth explaining. Voice can vary from low-volume grumbling to loud protest. He built from an insight: “…in the whole gamut of human institutions, from the state to the family, voice, however ‘cumbrous’ is all their members normally have to work with.” Loyalty might signal support for an organisation, a movement, a company, particularly where voiced opinions and suggestions are respected. But when all else fails, exit becomes a determination.

His goal was “both positive and normative” as he wanted economists to be broad, critical as he was of economic models that assume perfect rationality. Alacevich concludes that: “The entire analysis of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty rests on the fundamental observation that processes of deterioration are pervasive and unavoidable in human societies, and that no concept of maximisation, rationality, and efficiency can cancel out this unpleasant truth. “

Hirschman’s insights also have relevance to politics: Voice becomes more credible when exit is possible. This calls attention to electoral systems which facilitate a political culture – tolerant of dissent, debate, doubt, and political change.

An example, schools: If quality declines some parents (depending on economic ability) have a choice to exit – to send their child to a private school or to be home schooled. But this was not Hirschman’s main interest in raising this example. He had in mind the under-funded system of private schools in America. If a high-quality alternative is not on offer, then voice is all that is left. Hirschman feared dismal public schools versus shining results of private. “Staying” might be misinterpreted as loyalty, whereas the facts might point to no viable or attractive exits.

In Hirschman’s assessment, there are other implications: from conflict springs debate, allegiance, loyalty. Where there is a lack of conflict, far from this being a healthy sign of cohesion, it might be a sort of deteriorated loyalty.

Positively, in pluralist societies, conflicts can lead to negotiation, engagement, compromise, and ownership of shared solutions. If a solution to a problem exists, it lies in the process of looking for it. Alacevich sums up that this process is: “a supporting pillar of democratic societies, because it contributes decisively to forming the community spirit that a democratic market society needs.”

A criticism as well as point of praise was that the concept could be pressed into an unlimited range of possibilities. Yet Hirschman, always delving beyond initial implications and conclusions, jumped steps ahead. For example, he wrote about the paradox of disappointment with public engagement:

Overcommitment refers to the passion that the pursuit of public goals often produces, transforming participation and the time dedicated to the cause into a benefit instead of a cost – until activism fatigue breaks the spell. Under-involvement refers to the opposing idea that, especially in a democracy, institutional arrangements have been conceived to cool down excessively passionate behaviours.

In Hirschman’s worldview, the consumer-citizen is conceived very differently to economic man’s rational actor. Poetically, to emphasize his argument, Hirschman wrote: “Angst, omnipotence, denial of death, hubris and innumerable related terms point to a much more inherently dissatisfied and tense animal than the chooser between two or more preferences that mainstream economics – and, to a large extent, political science – present to us.” How to be disciplined in considering a multiplicity of factors, careful to avoid simplistic and narrowly based conclusions is the dilemma for the academy. For politicians, bureaucrats, and other decision-makers, it is their charge to make decisions. Reducing uncertainty is always a vital consideration.

As much as he studied changes in resource allocations, exogenous factors influencing political economy, he spent more time contemplating changes of people’s minds, the whys and wherefores, the social energy behind them. In Alacevich’s summary: “The experience of social activism and mobilisation was thus like a karst river, at times visible and strong, at times hidden underground, only to appear unexpectedly, often after a tortuous and unpredictable course.”

Hirschman’s focus on the Latin American import-substituting industrialisation model stood in contrast to the more compelling (and successful) export-led industrialisation of East Asia. Interestingly, he saw co-operatives playing a supporting role for voice “and a symmetrical protecting role against forced exit…” In Development Projects Observed (1967) and other works, Hirschman posited that co-operatives carried “symbolic value” in the most practical terms: as they are “an act of self-affirmation that fills people with pride” and could represent “a beginning of liberation [for] long-suffering and long-oppressed groups.”

Hirschman also saw potential to go the other way: “Co-ops, if successful, can turn into the very monster that they were supposed to slay. They may preach the rhetoric of participation and community mindedness, while in truth catering to a small and better-off portion of the population they say they represent… Though the good qualities may seem to inhere in an activity, they will often be present only at certain stages of a co-op’s history, and only in certain social and economic environments.”

He saw that sometimes a poor country, though rich in natural resources, has little bargaining power, but once foreign companies arrive to exploit the resources, the dynamic might change. To some extent, having built their plants in-country, those companies become captives to local political circumstances. A shift in bargaining power has occurred. Visits to Colombia and other Latin American countries led to the analysis and arguments expressed in The Strategy of Economic Development (1958) and Bias for Hope: Essays on Development in Latin America (1971).

Disappointingly, as Alacevich’s observes, Latin America’s “…deterioration of democratic discourse as a result of intransigent, closed, nondialogic attitudes became a central issue in [Hirschman’s] reflections.”

What of Hirschman’s influence and impact? In Alacevich’s summary: “Hirschman was admired and influential but had no ‘school’ behind him, he was not mathematical, and he was excessively interdisciplinary.” A lateral thinker, he wrote “beautiful breakthrough analyses” and resisted “pre-cooked recipes and standard explanations.” Hirschman’s writings can be described as readable, witty, scholarly, insightful, thought-provoking, incomplete. A common criticism is made of Hirschman’s cropped and elliptical analysis and expressions which sometimes begged further elaboration and justification.

Provocatively phrased is Alacevich’s suggestion that: “One could recapitulate Hirschman’s entire intellectual trajectory as an attempt to understand process of deliberative decision making and explore ways to find and activate the social resources that fuel those processes.” Alacevich concludes that Hirschman’s project for development economics as a distinct field from orthodox economics completely failed. Instead, it became an applied field of classical economics, itself a dynamic and plastic tradition now informed by Hirschman and other theorists.

Jesting with narrow conception of economics, Hirschman says: “Love, benevolence, and civic spirit are neither scarce factors in fixed supply, nor do they act like skills and abilities that improve and expand more or less indefinitely with practice. Rather, they exhibit a complex, composite behaviour: they atrophy when not adequately practiced and appealed to by the ruling socioeconomic regime yet will once again make themselves scarce when preached and relied on to excess. To make matters worse, the precise location of these two danger zones… is by no means known, nor are these zones ever stable.” How untidy this formulation must seem to many of his peers.

Alacevich concludes: “All Hirschman’s models and principles are interpretive lenses that can help us make sense of historical processes.” For this he will be long remembered as the author of arrestingly interesting arguments, books and papers that made a difference to thinking about problem-solving.

Constantly reconsidered, qualified, elaborated, and recast were many of his ideas, lines of argument, and conclusions. Subversive even to himself and his former writings, Hirschman thought this was the mark of an inquiring, creative spirit. He believed such an approach enhances the ability to interpret the world and thereby to change it. That is the difference Hirschman made to the timeless task of making sure political and dependent economic choices are informed, leading to good decision-making, rather those that are formulaic and unworldly.