Published in edited, shorter form in The Sydney Morning Herald, on line 2 July 2020, in print the next day under the heading ‘Erudite Thinker and Adviser Helped Shape Australian Foreign Policy’: https://www.smh.com.au/national/erudite-thinker-and-adviser-helped-shape-australian-foreign-policy-20200702-p558dg.html.

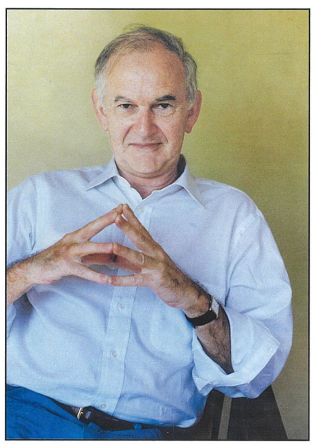

Owen Harries (1930-2020), foreign policy adviser, thinker, gadfly, editor, and advocate of the “national interest” realist tradition, died last week. His influence was profound in Australia and globally. He persuaded, stung, prodded those around him to think.

The son of David Harries and Maud Jones, he was born on 29 March 1930, in Garnant, a Welsh mining village in the valley of the River Amman – “an industrial hell on one side and lovely rivers on the other” in Wales, a land peppered with another people’s castles (the English), as he sometimes mentioned. Educated at Amman Valley Grammar School in Ammanford, he then studied at the University of Wales, Cardiff, where he graduated with honours in history, and went up to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he obtained an MA, and thereafter served as a pilot officer in the RAF (1952-54).

On 23 December 1953, he married a fellow Welsh Oxford history MA Dorothy Richards, with whom he was to have two daughters.

In the UK, he was impressed by Fabian ideas and temperament, and began a lifelong intellectual wrestle with what it means to be a fair-minded political realist. At Wales, the semi-Marxist historian E.H. Carr influenced him. Harries distilled from Carr’s The Twenty Years’ Crisis some major themes on foreign policy realism. Like the best thinkers, Harries often drew from others, reflected on their position, and decided his own view rather than merely “absorbing” another’s viewpoint.

The debate within himself, he encouraged in others. The issues he was interested in preoccupied others too. He made sure of that.

Migrating with Dorothy to Sydney in 1955 to take up a position in the Department of Tutorial Classes at the University of Sydney, Owen came under the influence of Harry Eddy (1913-73), with whom he worked. Thereby he was swepted into the whirlwind of Andersonian thinking. Eddy was an iconoclast, which in Sydney terms meant that he balked at the intellectual prejudices and conventions around him. Eddy was impressed by philosopher Professor John Anderson (Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney, 1927-1958) who had moved from Marxist to Trotskyist to independent pluralist thinker.

Unmoored from his own conventional leftism, Harries imagined himself as a conservative thinker, but in the Eddy spirit. He was never entirely to be relied upon for a safe, conventional opinion, even among friends. In the mid-1960s, Doug McCallum, the newly appointed Professor of Political Science at the University of NSW, headhunted Harries to join his Department. McCallum later wrote: “Owen Harries, one of the sharpest, most original and ‘live wire’ intellectuals one could encounter… was a Welshman who had imbibed socialism with his mother’s milk and did not question it until he came under Harry Eddy’s influence.” In 1976, Harries edited a book responding to Eddy’s thinking, Liberty and Politics.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Harries was a combative supporter of Australia’s defence of the South Vietnam regime. He thought a lot about the Left’s rhetoric about “liberation” and the struggle of the “Asian people” — as if everyone could be lumped into the same boat. Of this condescending perspective, in 1970 on the Moratorium demonstrations, he wrote: “Echoing Shaw’s celebrated definition of foxhunting, one might describe the Moratorium Campaign as an attack launched by the incoherent on the unconvincing.”

Lest anyone on the conservative side warm to the point, he also wrote in the same piece: “The government’s failure to make the case for the Vietnam policy and against its critics convincingly, forcefully and repeatedly, has been deplorable and inexcusable. It is not merely a political failure but a moral failure.” At times he tried to present the alternative case and was often bracketed on the other side of the debate with Dr Jim Cairns from the ALP Left.

Although Harries in the 1960s drifted to the right, he was a sceptic about some of his fellow passengers on the boat. His soft Welsh lilt accent and thoughtful words packed a punch. Donald Horne in Into the Open Memoirs 1958-1999 remembers conferences where the prize performer was Harries: “smack-on, disputatious, witty.”

Harries wrote a major assessment critical of Menzies’ efforts in 1956 when the Australian prime minister foolishly tried to inject himself into solving the conflict between Egypt, the UK, and France, who warred on the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Harries also wrote about Bob Santamaria, the Catholic social commentator demonised for his role in the ALP split in the 1950s. Harries liked “Santa”, but he thought his writings on defence and foreign policy were often repeating themselves and too simplistic.

Where Owen was once a commentator, academic researcher, an outsider dilettante on policy, this changed in 1975 when Andrew Peacock, the Shadow Foreign Minister, offered him a role as his adviser. Owen went to Canberra and began reading diplomatic cables, engaging with the intelligence community, considering in greater depth Australia’s role in the world.

In 1978, Doug McCallum told me: “Have you heard? Fraser has pinched him.” Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser seconded Owen to his staff. Fraser asked him to set up a panel of advisers to write a report on Australia’s engagement with the Third World. This included academics, an ACTU official, businessmen, and Harries as Chair.

Australia and the Third World (1979) was the report he mostly drafted, edited, and led the debate on. One Appendix was by a philosopher on morality and foreign policy. Harries described Australia as a western country with a difference. Which is to say he appreciated the country’s Western inheritance with its own interesting, distinctive features. A criticism of the Report was that it under-appreciated the Asian export-led drive typical of East Asia from the 1970s onwards. China was only then emerging from its self-lacerating cultural revolution. The Report urged that Australians should stop confusing itself and others with Third World rhetoric and to see the variety and differences of the many countries grouped together as the Third World, instead of as an amorphous grouping.

He clashed with Gough Whitlam, and when Fraser announced in 1982 “Professor Harries” appointment as Australian Ambassador to UNESCO, Whitlam scoffed that he was neither an Australian or a professor. (He was on leave as an Associate Professor at the UNSW.) Whitlam replaced him in late 1983.

I remember visiting Owen in February 1983 in Paris. He told me Fraser wept on a phone call that morning. If only he had waited. Hawke was going to win. Harries noted that the electorate were curious about Hawke: “When the public are curious about something, they usually want their curiosity satisfied,” he said.

From Paris, Harries developed a critique of UNESCO’s poor governance, which propelled him to global recognition. He published on the topic. The US withdrew funding in 1984. The UK similarly attacked the body’s corruption and waste of resources.

Harries joined the Heritage Foundation in Washington and engaged with other think tanks, including the Olin Foundation, debating America’s place in the world.

On one visit to New York, he took me to the offices of Commentary, and I met Norman Podhorertz, the editor. Harries knew, discussed, dined with, and debated the leading intellectuals interested in foreign policy in the US, the UK, Australia, and elsewhere.

Irving Kristol was an interesting, ex-Trotskyist, neo-conservative, who once famously quipped that a conservative is a liberal mugged by reality. Kristol had enormous influence, moving from radical anti-Stalinist leftist to moderate liberal reformer to neo-conservative. Pat Buchanan, one of Nixon’s advisers and speechmakers, insisted that they were neo-liberals, wanting to change the world too much to be real conservatives.

In the mid-1980s, Kristol, Harries, and Robert Tucker launched The National Interest, a foreign policy journal that would discuss America’s place in the world.

As the Soviet Union was crumbling, in 1989 Harries published Francis Fukuyama’s essay ‘The End of History’ essay, versions of Samuel Huntington’s clash of civilisations and other, interesting, influential assessments of the future.

In the first issue of The National Interest, the editors proclaimed: “This is a new magazine about American foreign policy. Its subject is the content, conduct, and making of American policy, and the ideas that inform all three.” They went on: “The present period resembles the critical years of the late 1940s. Now, as then, we find ourselves without a clear set of governing assumptions about foreign policy.”

Harries wanted the journal to stimulate and focus the discussion and attract contributions from leading foreign policy thinkers.

When the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, Owen paid a visit to Australia and gathered friends and asked us to imagine the world in twenty years time. Why are American troops in Korea? Do they need to be in Germany? Could and should the West see Russia differently in the future, as a normal power? Donald Horne quipped that in twenty years time those of us with a continuing interest in communism would be regarded as harmless cranks, like those interested in Commonwealth studies today.

Harries saw that anti-communism had united a fractious alliance of conservatives, realists, adventurers, “bear any price” idealists, as well as clear-eyed social democrats. He thought this coalition would fall apart in the post-Cold War world. Initially, he imagined that those of a conservative disposition would bear the burden of recasting policy. Harries believed studies of American decline were over-done, but feared that America’s appetite for a “damsels in distress” foreign policy courted disaster. He saw merit in the first Gulf War. There were limited aims: Iraq out of Kuwait, rather than regime change. He believed the second Gulf War would be a disaster. He knew many of the leading architects of American foreign policy and feared they were out of their depth.

Retiring from The National Interest in 2001, he and Dorothy returned to Sydney. He delivered the 2003 Boyer Lectures for the ABC, which conveyed a polemical point: Benign or Imperial? Reflections on American Hegemony.

The morality or immorality of politics is an inescapable issue for anyone thinking about foreign policy. In Jean-Paul Sartre’s play Dirty Hands, an experienced politician responds with exasperation to a younger critic: “How afraid you are to soil your hands! All right, stay pure! What good will it do?… well, I have dirty hands. Right up to the elbows. I’ve plunged them in filth and blood. But what do you hope? Do you think you can govern innocently?” The problem of dirty hands is a real one.

Harries thought prudence should limit involvement in foreign policy conflicts and that America should pick and choose its engagements. If this seemed too ruthlessly self-interested, Harries asked what were the alternatives? And he emphasised that seeking to impose American will, including democracy, could have unpredictable, messy, deleterious, and bloody consequences.

Harries wrote: “Those who idealise the Global Village seem to have little experiences of real villages – and the degree of envy, malice, meanness and vindictiveness that their intimacy can not only accommodate but foster.”

And: “To make the point even more starkly: the most interdependent social unit that human beings ever enter is the family — and it is in the family that most murders occur.” This is typical face-slapping Harries rhetoric.

In his last years, Owen was a Fellow of the Centre for Independent Studies and the Lowy Institute.

No systematic account of his thinking appeared in a single book. He might have considered answering the philosopher Tony Coady’s challenge that there is wide diversity in “the things affirmed as basic to their outlook by different (or even the same) realists.” But this was not to be. His answers are found in various books he edited and in around 300 articles he penned in journals and magazines.

He sometimes quipped that open minds are often empty heads. He drove himself and many others to reassess assumptions, interests, and prejudices. His influence will be long-lasting.

He is survived by Dorothy, his lifelong soulmate — who travelled a similar journey, adding a softer touch, seeing whimsy in human folly — and their two daughters Rowena and Jane, and one granddaughter, Grace.

Postscript (2020)

If there was one university teacher who helped shape the person I became, it was Owen Harries. Of course, there was not just one person who influenced me. But Harries got me out of my ‘comfort box’ to see the world from others’ perspective including, especially, those I disagreed with.

I sometimes murmured that on foreign policy my heart was idealist, my head realist. Everytime, I thought of Owen, his distinctive way of thinking which invited assessment of how much more complicated a situation might be. He was the best antidote to optimism-bias; and like umpteen antidotes, it was disorienting and unpleasant to take the medicine.