Delivered to a function organised by Quadrant magazine in Sydney.

I am sure that most academics would shudder to think that one of their former students – on the strength of a single year’s experience – would purport to explain to such a gathering what he was like as a teacher.

So, from the outset, I must emphasise that my remarks are mostly based on my knowledge of Owen in 1975 when, as a Third Year Honours student in Political Science at the University of NSW, I was enrolled in two options taught by him: Comparative Foreign Policy and Australian Foreign Policy.

When Richard Krygier asked me yesterday to say some words on Owen, I decided last night to search through my lecture notes and papers to find some information that might be helpful.

I found two versions of a paper I prepared on ‘Dr Cairns on Asia’.

The first version was what I presented to the tutorial class. In class I stated: “This paper will attempt to… argue that Dr Cairns’ ideas concerning the ‘Asian revolution’ are generally correct despite the confused and sometimes contradictory nature of some of his writings.” Owen’s reply was devastating. I felt that what he was saying was true, but I did not want to believe him. Well, after presenting my views and thinking about the man, I underwent a change of mind.

I am happy to say that the second version of the paper maintained the position that Cairns’ arguments were confused and sometimes contradictory. It also argued that Dr Cairns was wrong about much that he had written.

Partly as a result of Owen forcing me to think about Cairns and, separately, Doug McCallum’s course on Marxism – which introduced me to the ideas of Karl Popper – I ceased to be a supporter of the Left and moved to my present and determined position as an anti-communist social democrat.

For Owen’s contribution to this development I will always be grateful.

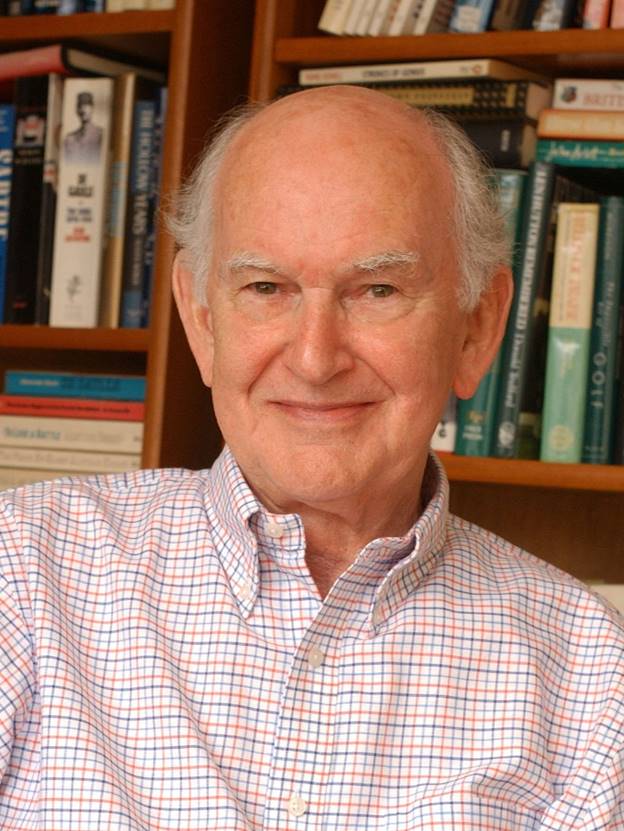

Owen was – and is – a very fine academic who encouraged all of his students to think for themselves.

He had the gift of the Socratic approach to teaching – by which I mean the ability to throw up complex questions and suggest difficulties in arguments to his students.

There were four things that I particularly remember about his teaching:

First, appreciate that ideas are important. In the end, Owen liked to emphasise, ideas triumph or fail, can influence events and can be powerful weapons with political consequences. E.H. Carr’s Twenty Years’ Crisis (1939) was sometimes cited to illustrate this view.

Second, respect an opponent’s motives and, in intellectual argument, challenge the strongest possible case against yours.

Sometimes the most tempting thing to do is to attack straw men. The hard and honest thing is to consider your opponents’ best case possible (even when, sometimes, they are weaker in presenting that than you can be).

It has now become a habit of mind to apply this to those things I do – to try to live up to Descartes’ maxim of questioning everything, while respecting opponents.

Third, be critical of anyone without opinions – such as the left-liberal no-nothings with no definite opinions on anything.

Owen liked to say that those who boasted that they were open-minded often seemed empty headed.

Fourth, understand the value of good writing. Anyone who has read some of Owen’s essays can only be impressed with his ability to write thoughtfully, logically, impressively.

All of those characteristics of thinking, challenging, and expressing argument have left a lasting impression.

Apart from his academic and personal qualities I am impressed with his feel for politics.

I last met Owen in Paris in February 1983 when he was still Ambassador to UNESCO. This was soon after the announcement that there would be an election in March of that year.

I suggested that Hawke would win; but I did not know how Hawke would go as Prime Minister.

Owen said that he too was curious to know how he would perform as national leader.

“When people are curious they generally want their curiosity satisfied”, Owen remarked.

From that point I was certain that Hawke would win.

But I wonder whether Owen’s curiosity has been satisfied.

Postscript (2015)

After university, I stayed in touch with Owen (1930- ), visiting him overseas; the Paris trip was after a visit to Israel. (For decades afterwards, he said later, he believed I must be Jewish. My instant response was: “No. No one is perfect.” Of course, I am proud of my Catholic origin, with a deep love of many Jewish traditions and the Jewish people generally.

I remember on one trip to the Commentary magazine offices in New York briefly meeting Norman Podhoretz (1930- ) with Owen arranging my access to the journal’s early issues – I wanted to look up the writings of Franz Borkenau (1900-1957), in the days prior to internet searches and imperfect Australian holdings of international journals. On another occasion I met Irving Kristol (1920-2007), whose office was next to Owen’s in Washington DC, where Owen relocated in co-founding and editing from 1985 to 2001 the highly influential National Interest foreign policy magazine. Professor Doug McCallum (1922-1998), who co-supervised my honours thesis in political science (on Karl Popper’s philosophy) at the University of NSW, once told me that when Owen was Foreign Policy adviser to Foreign Minister Andrew Peacock, that Prime Minister Fraser said: “I am the PM, I want him for myself!” So Owen moved from Foreign Minister adviser to the PM’s office. As Chairman of the Committee on Australia’s Relations with the Third World led to one of his most impressive activities – authorship of the report Australian and the Third World (1979), known as the Harries Report. During 1982-83 he was Australian Ambassador to UNESCO. In 1983-85 he was a fellow at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, DC.