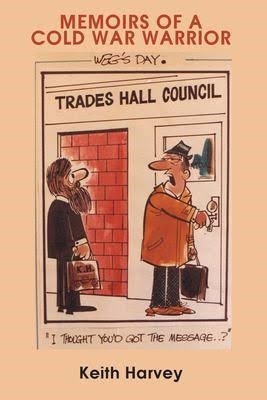

Review: Keith Harvey, Memoirs of a Cold War Warrior, Connor Court Publishing, 2021.

This is a lucid and interesting story by Keith Harvey: From university activist in the Democrat Club at Monash University in the early 1970s, gradual attraction to the ideals and works of the National Civic Council (NCC), conversion to Catholicism, marriage, children, recruitment to the anti-communist union cause, union work, including the Victorian Trades Hall Council (VTHC) in 1977-78 (it did not end well), then the Federated Clerks Union (FCU) to retirement, and attraction to the ideals of the Australian Labor Party in coalition with Christians concerned with social justice.

What is unusual about these memoirs is that Harvey was not a product of the ALP split (he was a toddler at the time). He was as a recruit decades later, who saw consistency and purpose in the “old Catholic right” of the Victorian Movement. There are few such memoirs, if any, from those of his vintage who fought and stayed true (as distinct from those who returned from battles disillusioned and in apostasy.) Harvey uses the term “vocation” to capture how he and colleagues of religious inclination saw union work, seeking better pay and conditions for working people. Ideals of a better world were turned into practical reality.

The book, dedicated to his wife and family and for “all those who kept the faith”, also mentions Harvey’s ancestors, one a progressive farmer, another a utopian socialist, as if there is a consistency of purpose, a coalition over time that reflects the grand, boisterous coalition that was and (to some extent) still is the Australian labour movement.

Harvey was employed by the Victorian branch of the FCU from 1979, then the national office of the union until it disappeared in 1993 — amalgamated with several unions into the Australian Services Union (ASU) where he worked until 2013.

The book’s first Chapter, ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’, alludes to Orwell’s novel, communism, and the year Harvey re-joined the ALP (having previously been a member from 1974-78). 1984 was the year the Victorian branches of the Clerks, the Shop Assistants, the Ironworkers and the Carpenters and Joiners, applied to re-affiliate to the Victorian ALP. It is a nice scene setter.

Chapter 2 is ‘The Monash Soviet’ (which was really the Beijing Soviet, as the university’s Labor Club and much of Monash student politics were dominated by Maoists and other crazies.) A future Labor Premier of Tasmania, Jim Bacon, then a Monash Maoist, was a contemporary, as were future Builders Labourers Federation activists. Harvey felt revulsion at far-left chants “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, dare to struggle, dare to win” in Vietnam war protests and their sympathy for the murderous Cultural Revolution in China. Harvey joined the Democrat Club, a student body originally inspired by the DLP.

Chapter 3 affectionately traverses activities as an Organiser from 1972 with the Rope and Cordage Workers’ Union, one of those small unions that were swallowed by amalgamations into various conglomerate unions following industry changes.

Chapter 4 describes Harvey’s aborted placement in a key research position in the VTHC. The book’s cover features a cartoon by William Ellis Green in the Melbourne Herald showing an official at Trades Hall locking a door and barring Harvey from an office he was dismissed from. “I thought you’d got the message” was the caption. This refers to his recruitment by Ken Stone (1926-2006, VTHC secretary, 1969-1985), a moderate, who saw Peter Marsh (VTHC secretary, 1985-88) as his replacement, but hoped for a cleanskin, right-wing Labor activist who could make sure the numbers were there for the future. But Harvey’s NCC-links were used by the Left to challenge control of the VTHC, and Stone felt disappointed Harvey’s background was not fully disclosed to him. Harvey was sacked. Stone’s instincts were right, as when Marsh moved on, airily dismissive of factionalism, one of Australia’s most prominent Left unionists and recent ex-communist John Halfpenny (1935-2003) took over (VTHC secretary, 1988-1995). In fairness to Harvey, he says he disagreed with many of the policies of the NCC; he respected their anti-communist zeal more than anything else, and this rings true.

Chapter 5 is about working for John Maynes (1923-2009) and is the most fascinating and well-written part of the book. Miranda Priestly, the exasperating character in the film The Devil Wears Prada (2006) is an unlikely comparison at the start. Maynes led the Clerks’ ALP Industrial Group from 1946 to his retirement from union office in 1992. Harvey worked closely with Maynes as his power-base collapsed, and Maynes’ wordy discourses on anything and everything, bossiness, forgetfulness, and ego made him hard to work for. Gore Vidal’s description of Gough Whitlam comes to mind: It was sometimes hard to tell the difference between vanity and over-weaning vanity. Yet, at heart, Harvey sees Maynes as a good and brave man, whose better days were behind him.

Mayne’s team won control of the Victorian branch of the union in 1950. By the early 1950s, many of the officials elected by the ALP industrial Groups across Australia were young, in their late 20s and early 30s. A few too many aged in situ.

Maynes dominated the FCU’s policy work: technological change, equal pay for female members, family income assistance, and international unionism. In 1988, however, Victoria was lost to the ALP Left and allies. Interestingly, and not widely known, Maynes did not have a full-time paid union position until late in his career, after the NCC split in 1980-82 when Maynes fell out completely with Bob Santamaria, the NCC impresario and dominant media and organisation personality. Prior to that, Maynes was the NCC’s full-time industrial officer. Nearly all the industrial activists in the NCC, having been sacked, retrenched, or departed in disillusion, formed a new organisation, known as Social Action, in which John Maynes was initially a key figure. But this too petered out and this provides some context for why some of the erstwhile NCC-aligned unionists in Victoria were so receptive to Bob Hawke’s urging that they re-join and heal the ALP Split.

The next Chapter discusses international work, including the Cold War union rivalries in the Pacific. Chapter 7 is bitter-sweet: Solidarność support, Cold War victory, while losing the Clerks Union to the Left. The last Chapter is an account to reconcile family, his experiences, the labour cause, and the Catholic social justice tradition.

An Appendix contains a short-hand summary of why the anti-communist fight was important, highlights the significant beachheads and control of key unions by Australian communists and their allies, and the mess/tragedy of the ALP Split. This is Harvey’s cogent estimate of the period before he came to prominence. He is right to say that for 30-years the Victorian ALP did everything to head off unity with the DLP ex-members, as readers of Paul Strangio’s account of Labor in Victoria, Neither Power Nor Glory (2012), can discover.

Harvey concedes that through the years covered he was mainly a loyal foot soldier, sometimes a conspicuous one, often with little direct understanding of or involvement in key decisions. Time, retirement, and reflection enable perspective. The book’s footnotes display genuine scholarship, a handy index assists the reader. Through zest, determination, and certitude he rose to a significant place in the FCU only to have the union crumble underneath him. The best that can be said of anyone is they worked honestly, conscientiously, for noble ideals, uncorrupted by base temptation. This was Harvey’s vocation.