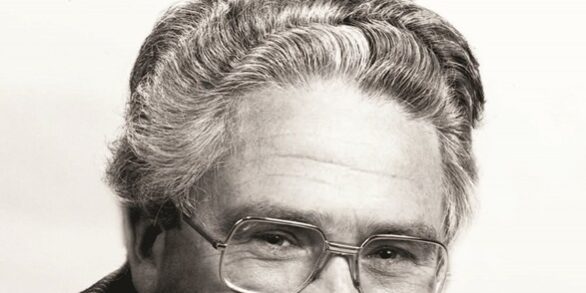

It is a spectacular irony that in the 21st century, so far, the Australian whom in sympathy most popularised Catholic social thought is a committed atheist and Fabian socialist who youthfully flirted with joining the Communist Party. This is only one of the fascinating features of the life of Race Mathews (1935- ), explored in a well-researched biography by his wife and noted author, Iola Mathews.

Race Mathews. A Life in Politics is divided into 25 chapters, the first four were written by Race, before blindness and memory loss made completion impossible. In comprehensively finishing the memoir, heavily drawing from books and articles by and interviews with Race, his spouse lives up to Iris Murdoch’s adage that understanding another person is “a work of love, justice, and pity.”

Race Mathews is best known as Principal Private Secretary to Gough Whitlam, 1967-1972, Federal MP for Casey, in Victoria, 1972-75; Principal Private Secretary to several Victorian state Labor Leaders of the Opposition, 1976-1979; Victorian state MP, 1979-1992, including as Victorian Minister for Police and Emergency Services, and Minister of the Arts (“pigs and prigs” as a Melbourne Age writer quipped), and as Minister for Community Services from 1987 to 1988; then as academic and researcher.

He is the author of numerous books on politics, cooperatives, and economics. These include Building the Society of Equals: Worker Co-operatives and the ALP (1983); David Bennett: A Memoir (1985); with David Burchell, Labor’s Troubled Times, (1991); Whitlam Re-visited: Policy Development, Policies and Outcomes (1992); Australia’s First Fabians: Middle-class Radicals, Labor Activists and the Early Labour Movement (1993); Jobs of Our Own: Building a Stakeholder Society (1999); Turning the Tide: Towards a Mutualist Philosophy and Politics for Labor and the Left (2001); and Of Labour and Liberty: Distributism in Victoria, 1891-1966 (2017).

The last three of these espouse the concept of “Evolved Distributism”, the application of Catholic principles in a social democratic spirit. Mathews once said: “I am not a Catholic, my concerns are secular. What interests me about Distributism and Social Catholicism is their place in the history of ideas, and their promise of a better social order.” Distributism is a word that denotes the Catholic idea of diffusion of power, responsibility, and organisation to cooperative and mutualist societies, consistent with Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum, and subsequent church-sanctioned and other iterations.

In Bob Santamaria’s 1954 ‘Movement of Ideas’ speech, that excited tirade delivered with celerity to a spellbound audience of Catholic Social Studies Movement members in Victoria, he warned of the dangers of fellow travelling, naïve middle-class intellectuals, parsing their way through the Cold War seeking peace, harmony, and understanding. Instead of heeding the urgent entreaties of those standing for freedom and fighting communism this type, in muddled entropy, ended up assisting the enemy. This, mainly because they lacked moral and intellectual clarity.

Mathews, at the larvae level of political awakening, might seem destined to fulfill ‘Santa’s’ prophecy.

Hewlett Johnson’s admiring The Socialist Sixth of the World turbo-charged the teenage Mathews’ political interests. He proclaimed himself leader of communist students at Melbourne Grammar. After teacher qualifications, in the country, he joined the Australian Labor Party after the ALP split of 1955 when, in Victoria, most Catholics left the party. He was an Evatt supporter. In this study, Mathews in the late 1950s is barracking for nuclear disarmament and serving as campaign director for diehard Soviet fellow-traveller Sam Goldbloom, the Evatt Labor candidate, in the seat of Latrobe in the 1958 federal elections. Goldbloom was a leading light in the Victorian chapter of the Congress for International Cooperation and Disarmament, and active in the World Peace Council and other communist fronts.

What made Mathews better than his political beginning was a curious, lively mind. Plus, he got lucky in friendship. His closest friend, David Bennett, grandson of General Sir John Monash, was a left-wing opponent of the communists, who steered Mathews away from youthful infatuation with New Soviet Man. Mathews met him as a teacher in country Victoria. News of Khruschev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes, in a speech delivered at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, reached Melbourne. The Soviet’s bloody suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 provided contemporary evidence to match what Mathews read, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, and others were saying about ‘really existing’ communism.

Mathews switched from neophyte ‘Comm’ to committed democratic socialist. He got active in the Victorian Fabian Society, an organisation Bennett co-founded in 1947, and slowly, his eyes opened. In 1960, he applied to be Victorian State ALP Secretary; the next year he sought appointment as ALP state organiser covering country Victoria. Both times cursory rejection followed. The hard left ran Victorian Labor and they suspected an independent thinker.

A minority of thoughtful Victorians coalesced in the Fabians Society did some hard thinking about policies and priorities. The book quotes Mathews’ observation that “the Fabian Society became Whitlam’s think tank.” As Principal Private Secretary to the Leader of the Opposition, Mathews joined Whitlam’s staff. His boss was “hero, father figure and mentor.” Mathews and colleagues helped craft ideas on needs based funding of schools, the idea of a national Schools Commission, and concepts favouring universal health-care, Medibank, later recast as Medicare in the Hawke era.

Mathews sought out others, experts, to help devise policy. In this achievement alone, he was an influential, effective, and significant advocate for his party. Years later, at the launch of Australia’s First Fabians, Whitlam said: “Fabianism is not and never has been a body of fixed doctrine… the key to the Fabian approach [is] a belief in the application of the intellect to human affairs, stubborn faith in human ability to solve the problems of human life through the application of human reason.” Those words encapsulate politics as practiced by Mathews.

For political historians, the book is insightful about a career, and Mathews’ participation in events ranging from the dissolving of the post-split Victorian ALP branch in 1970, its reconstitution, life as a Federal MP, and later State MP.

Tragically, Race’s wife Jill née McKeown, died in 1970, aged 34, mother of their three children. After a close personal liaison with Ainsley Gotto, the then Prime Minister Gorton’s Chief of Staff, Race met Iola Hack, journalist, and they married in 1972, and they had two children of their own.

In an interview at the National Library, quoted in the book, Mathews says, “Ideas and policies have always interested me more than other aspects of politics; I am not a natural politician…” That is a clue as to why his intellectual journey – and fascination with Catholic social thought – matters.

After defeat in the 1992 state election, Mathews’ research and academic activities accelerated. Even as an unhorsed minister and government backbencher in the dying days of Victoria’s then Labor government, Mathews did part-time teaching at Monash.

Significantly, as early as 1981, a study of Mondragon was recommended to him by Shirley Williams, a fellow Fabian, active in the British Fabians, a well-loved Minister in past Labour governments, who was soon to defect to the UK Social Democrats. (Perhaps her Catholicism led her to think the social experiments covered by the rubric ‘Mondragon’ might be interesting to explore). Mathews read all he could about what Fr José Maria Arizmendiarrieta had inspired in the Basque country in Spain, a variety of mutuals, self-governing co-operatives. Iola notes: “from an early age, Race searched for a political philosophy to live by.” While still a Victorian government minister, with two other Victorian state ministers, Mathews co-wrote The Cooperative Way: Victoria’s Third Sector (1986). He grew frustrated, however, by indifference and lack of follow-through. Of Mondragon, then a large group of 100 worker cooperatives owned by 17,000 workers, Mathews said: “I was astonished. This was the ‘society of equals’ I’d been looking for all my life”. In 1997, Iola and he travelled there: “Mondragon fulfilled the hopes of both distributists and democratic socialists.”

Mathews had a rethink. By the early 1990s, the biographer writes: “Race had recently discovered that the cooperative movement was linked to the Catholic social justice movement. At first, he was dismissive, because he associated the teachings of the Catholic Church with B.A. Santamaria, who had done so much damage to the Labor Party. But Race’s attitude changed…” From there, Mathews recovered a near-forgotten strand in the history of Australian civic culture and society, writing about interesting pioneers in credit unions and associated fields. In a 1998 speech, Mathews said Australia’s credit unions had a proud history, many “founded by families meeting after mass in Catholic parishes, or working people getting together in their workplaces, and responding to a community need.” But this achievement was threatened, as they were “at risk of takeover and demutualisation by corporate raiders.”

An examination of that claim would make interesting reading. There was an element of untormented certainty in what Mathews now claimed should be the ‘third way’ for organising society, of what contemporary Australian Labor might stand for. Mathews notes that “Gough regarded it as a deplorable idiosyncrasy and departure from reality, on my part.”

For over forty years, through two doctorates, including one in theology, as a minister, MP, polemicist, and propagandiser, Mathews has argued that a society of equals, the dignity of mankind, is enhanced through the understanding and application of good principles. The experience and record of unions, mutuals and co-ops, and specifically Catholic-inspired organisations in the twentieth century, offer rich potentialities.

Iola Mathews’ biography beautifully explains a man; hers is an intellectual biography and a love letter. She tributes his “best qualities … his intelligence, wide-ranging knowledge, idealism, integrity, dependability and kindness.” Those words at the beginning of the book soar in credibility when turning the last pages. His example, journey, mistakes, disappointments, and striving are fascinating.