Published in the Southern Highlands Newsletter, May-June 2019, pp. 49-53

Australia’s greatest Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, entered the office with expectations that were precarious and low. His 1979 Boyer Lectures on ABC radio were wide ranging and lightweight. Ideas were kite flown as if they were wistful suggestions untied to each other and unmoored to earth.

In Parliament from the electorate of Wills, after the October 1980 federal election, he did not shine. I remember, though, the eager anticipation of Hawke, MP. At the time Michael Danby rang me to say that a friend and another future MP, Peter Costello, drove him to ACTU headquarters on Swanston Street so they could both witness history when Hawke announced his candidature for parliament at a press conference in August 1979. Such enthusiasm was widespread.

At the time Hawke entered Parliament, I was in my third year as Education and Research Officer of the Labor Council of NSW, sponsored into the role by Bob Carr and Barrie Unsworth. I had much to learn. My activities in the movement included membership of the Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee of the ALP in NSW, honorary organiser of Labor Friends of Israel, Secretary of the Labor Council for Pacific Affairs, Secretary of the NSW ALP Education Committee.

I took on roles on committees in the ACTU covering education, training, and international affairs. Carr quipped that I was now the Suslov of social democracy in NSW – an ironic allusion to Mikhail Suslov, Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the unofficial chief ideologue of the Party from 1965 to his death in 1982.

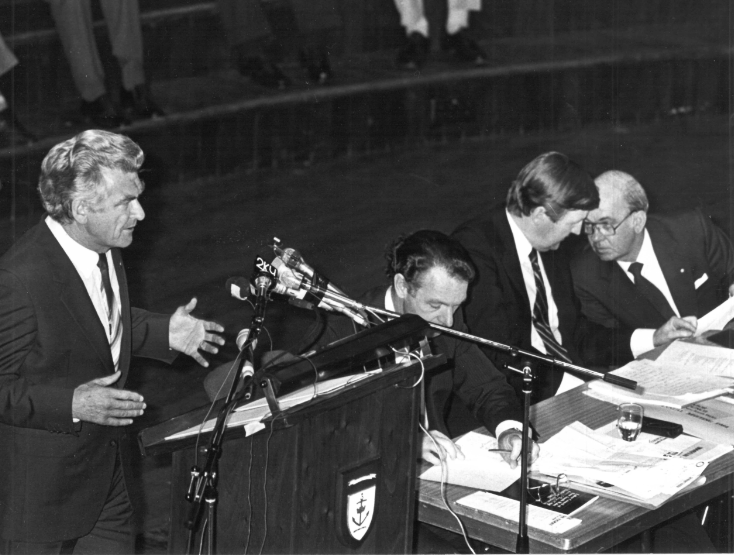

I learnt from John Ducker and Barrie Unsworth what they thought of Hawke: they opposed his election as ACTU President in September 1969, preferring Harold Souter, the then ACTU Secretary. Hawke won with the broad Left (including the Communist Party in its various guises) and the Centre, with parts of the Right breaking off to support him. A few years later, the NSW Right became his ally.

All at once, as ACTU President, Hawke was mercurial, vain, brilliant and a surprisingly consensus figure. The scars and scabs of the ALP splits of 1955-1957 were still points of aggravation, suspicion, and resentment. Hawke was a healing, pragmatic figure.

With entrepreneurial flare, his engagement with human rights issues (including the fight against apartheid), his ability to cut through at a mass meeting of auto workers, to the business sector, his love of Israel and Jewry (no one did more in the international union movement to campaign for the free migration of Jews from the Soviet Union), won wide admiration.

It is hard to believe forty years later but the ACTU was then a small shop, smaller in staffing and resources than the Labor Council of NSW. Before funding from affiliates was secured, the latter looked at a decision to fund an ACTU Legal Officer Alan Boulton effectively as a favour.

When his parliamentary career began, Hawke had the affection of the major Left leaders in the unions and new friends on the Right. He was regarded, however, with suspicion within some parts of the Left of the ALP, particularly by Arthur Gietzelt, notwithstanding that his brother Ray, as national secretary of the Federated Miscellaneous Workers’

Union, was one of Hawke’s key confidants and, arguably, the strategic brain in organising his ACTU victory in 1969.

A person of such natural and striking abilities, articulate on radio and television interviews, a larrikin and raconteur, of intellectual depth and passion, sounded like a Labor leader worth backing. Against those positives were Hawke’s alcoholism, sometimes nasty drunken behaviour, serial womanising, indications of manic depressive behaviour. Blanche D’Alpuget’s biography, Robert J. Hawke (Schwartz 1982), addressed the rumours, accounted for the making of the man, and created its own fandom.

By confronting some of Hawke’s worst features, as well as describing his personal and intellectual development, his grappling with demons, lanced some of the scepticism. No finer biography of any Australian Labor figure has ever been written. No book on Australian politics has done more to make its subject warmer, more interesting, credible – and electable.

There remained the problem of Bill Hayden, Opposition Leader, who was widely admired though regarded with dark suspicion by sections of the NSW Right, NSW ALP General Secretary G.F. Richardson in particular, chiefly because of Hayden’s support of the small Centre Left faction, a potential threat to both the Left and Right. Hayden as Minister for Social Security in 1975 had successfully introduced Whitlam’s greatest reform, Medibank, and later that year, as Treasurer, was disciplined and determined, balancing an otherwise turbulent government.

Long have I thought that Fraser moved to block supply in October/November 1975 because he feared that another year with a reinvigorated ministry with Hayden (Treasurer), Jim McClelland (Labour and Immigration), Joe Riordan (Housing and Construction), Joe Berinson (Environment), John Wheeldon (Social Security), and Paul Keating (Northern Australia) – though it is arguable whether his immense future impact on the life of the nation was in any way then discernible, would considerably enhance Whitlam’s chances of re-election.

The Whitlam government’s wage blowouts, strike happy militancy and breakdowns in relations between the unions and the ALP, partly propelled in an oil-dependent world by the 1973/4 global shocks – with massive increases in petrol prices engineered and sponsored by the Organisation of Petroleum Export Countries (OPEC) – led to rapid inflation, then the corrosive cycle of wage and price inflation in Australia. We had reason to wonder about the efficacy of the federal Labor government. Hawke, obviously, bore responsibility for some of this. Australia, say in comparison to Japan (which prior to 1974 had a worst strike record than that of Great Britain), lacked strategic leadership, industrial and political at the top.

Lessons learnt, could Hawke be instrumental in managing and presenting respectable industrial relations behaviour in the next Labor government? That was one reason that, as a candidate, not yet elected an MP, Hayden appointed him Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations for the 1980 election campaign. To their credit, the challenge of getting the management of wages and prices right drove the ACTU (led by Peter Nolan, then Bill Kelty) and Ralph Willis, the shadow treasurer, to conceive of “the Accord”.

In Opposition, as Keating was to acknowledge years later, Hayden reality-checked the ALP to accept the American alliance and the joint security facilities. Meanwhile, in the late 1970s, ALP Left Senator Arthur Gietzelt was denouncing them as “U.S. bases” and extolling the merit of dialogue with and learning from the French and the Italian communist parties. Hayden and Willis seemed eminently sensible and non-threatening economic leaders. More than that, they had ideas.

After losing the 1980 election, there was a growing clamour for Hawke within sections of the movement. The parliamentary Left were mostly opposed. Keating thought Hawke was all ribbons and show pony. Otherwise, within the unions and among MPs, some marshalled with the undoubted organising abilities of G.F. Richardson, there was impetus for Hawke. Hayden, dogged, worried, respected, held on as Opposition Leader.

A turning point came in late 1982 when the Labor candidate was defeated at the Flinders by-election on 4 December in a seat Labor expected to win. In the ensuing panic, on 14 January 1983, dumping Willis, Hayden appointed Keating as shadow treasurer – a role that Keating originally resented. He genuinely felt for Ralph Willis.

A week later on a Friday afternoon, I remember Keating coming to the 10th floor of the Labor Council building to see Barrie Unsworth and John MacBean, holding two plastic bags of economics books just purchased from Angus and Robertson. “This is what this bastard Hayden has saddled me with this weekend.” That is, the need to bone up fast on economics and get on top of his new portfolio.

Interesting that two “unsuccessful” ALP Opposition leaders, Hayden and Latham, were to “gift” to successors particular economic spokespersons roles that were decisive in shaping the reputation of subsequent governments. Hayden sponsored Keating for Hawke; in contrast, in 2004 Latham thought Swan as shadow treasurer was going to blow up, exposing his own incompetence. Rudd and Gillard inherited that decision.

Within a few months of the Flinders by-election, Keating was shadow treasurer and was now supportive of Hawke. The walls of Jericho around Hayden fell – as did he. On 3 February 1983, Hawke became leader of the ALP – on the same day Malcolm Fraser, hoping to catch the ALP “with their pants down” before they could change leaders – secured a double dissolution election.

During the subsequent election campaign, on holidays, I popped into the Australian Embassy building in Paris (beautifully designed by Harry Seidler) to see my former university teacher Owen Harries (he taught me Australian foreign policy), then Australia’s Ambassador to UNESCO.

On his appointment Whitlam denounced the Welsh-born academic and former foreign policy adviser to Prime Minister Fraser as “not a Professor and not an Australian.” Earlier, I still recall the shock on Owen’s face when he saw me with Whitlam badges festooned on my shirt in November 1975 before the academic year ended. He was a mentor in thinking about issues, in writing, and crafting an argument. At our lunch, Owen said that early that morning the Prime Minister (Fraser) phoned and discussed his chances, Fraser breaking down, sobbing briefly, and regretting that he never gave himself the chance to test Hawke in the Parliament as Opposition Leader. Fraser knew he would lose.

The rest is history – the formation of the Hawke Labor government, four election wins, a legacy – as other contributors discuss.

Five particular memories stand out, if I might briefly recall.

First, on foreign policy, Hawke had the big picture and was an innovator – the formation of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) organisation for one.

Ross Garnaut’s 1992 piece in the Australian Quarterly on “Australia’s Asia-Pacific Journey” is the definitive article. Soon after his March 1983 election victory, I invited Bob to meet US union representatives of the Labor Committee for Pacific Affairs on a visit to Australia. He agreed, meeting us at the old Parliament House in Canberra. Legendary US teachers’ union official Albert Shanker led the delegation. We Cold War social democrats were concerned about Soviet penetration of the Pacific island unions and neglect by Australia of fostering good economic ties in the South Pacific.

Second, the Economic Planning Advisory Committee (EPAC) meetings were effective means of capturing feedback and for canvassing policy ideas. I attended on behalf of the ACTU as an alternate delegate, then delegate (from 1987). Hawke chaired the meetings, quickly moved through the agenda, read the room well, and strategically invited contributors from unions and business to speak. These meetings were sometimes derided on the Left and conservative Right as “corporatism”, as if business and union leaders meeting and discussing issues was some kind of echo of Mussolini’s rule. It showed to me, however, that Hawke listened, considered, and acted and that this Cabinet government style of management made for good administration.

Third, as a result of the Tiananmen Square protest in June 1989, Hawke was courageous in calling China’s leaders to account and expressing sympathy for the students. I called him a day or two after the June 4 massacre, because the Labor Council and the Federated Municipal Employees Union had put a black ban on the delivery of garbage from the Chinese consulate in Elizabeth Street, Sydney.

Acting Foreign Minister Michael Duffy gave me a number to call. I did not want Hawke to get upset by, or to veto, our action. I knew one union leader, Lee Cheuk-yan (subsequently a member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council from 1995-2016), arrested the morning after the night before – pulled off a Dragon Air Flight going from Beijing to Hong Kong. Hawke told me that if he had a problem, he would let me know. Hawke’s later decision to let approximately 40,000 Chinese nationals stay in Australia had long term strategic and beneficial consequence for Australia.

Fourth, when in 1989 Michael Costa and Mark Duffy co-wrote a paper for a strategy discussion at the Labor Council, it surfaced in the media. The paper argued that there was too much conservative foot-dragging by the movement, State and Federal, to facilitate enterprise bargaining. There were calls for their dismissal. I defended their right to think and express their views. Publication in the media was counter-productive. We agreed on a strategy. I was told no-one had been shown a copy outside of the Labor Council office. Hawke called me to say it was naïve to think one of them had not themselves leaked.

Alas, I subsequently learnt that one of my colleagues shared a copy with former Labor Council Industrial Officer, John Tolley, who gave it to Lindsay Fox, who handed it over to Andrew Peacock, who sent it on to shadow Industrial Relations minister Fred Chaney, who then faxed a copy to NSW Industrial Relations Minister John Fahey. Peacock divulged the story to the Sydney Morning Herald in Sydney and the Herald-Sun in Melbourne. Unlike some others like, disgracefully, the Australian Journalists’ Association in a fit of factional animus, Hawke never called for anyone’s firing for thought crimes.

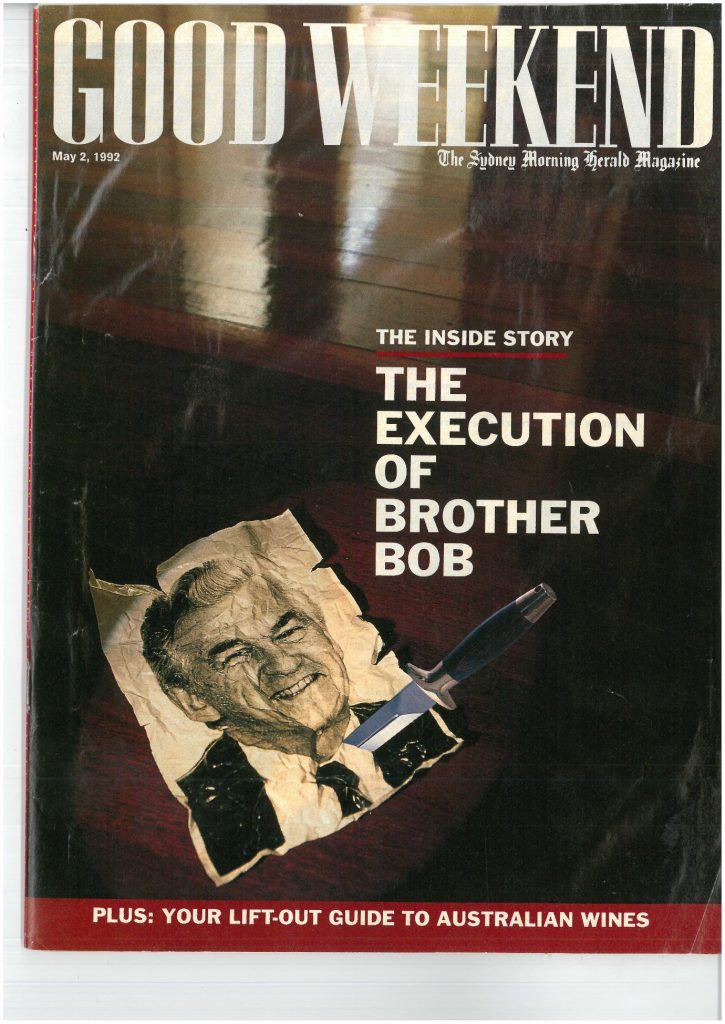

Fifth, I was surprised by the insurrection against Hawke in 1990-1. I was not aware of the Kirribilli Agreement, although obviously, there were tensions between Prime Minister and Treasurer. When I became Assistant Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW in 1984, and especially after becoming Secretary in 1989, I dropped most of my activity in the ALP. So I wasn’t keeping tabs on Canberra. Greiner and Fahey were enough to handle in NSW. It was important in my view to fully concentrate on union affairs.

When Keating delivered his “Placido Domingo” speech in December 1990, which berated past leaders as inadequate, describing John Curtin as a mere “trier”, there were stories that Hawke might sack Keating. I thought I could craft a media release defending Keating and urging that Prime Minister and Deputy get on with each other for the good of the party. The AFR wrote this up as a one-sided plea for Hawke. Keating, whom I always admired and never canvassed against, became an implacable opponent. I did not understand immediately, but then and there the cookie of a potential life in parliamentary politics began to crumble.

The article as it appeared in the Newsletter:

Postscript (2019)

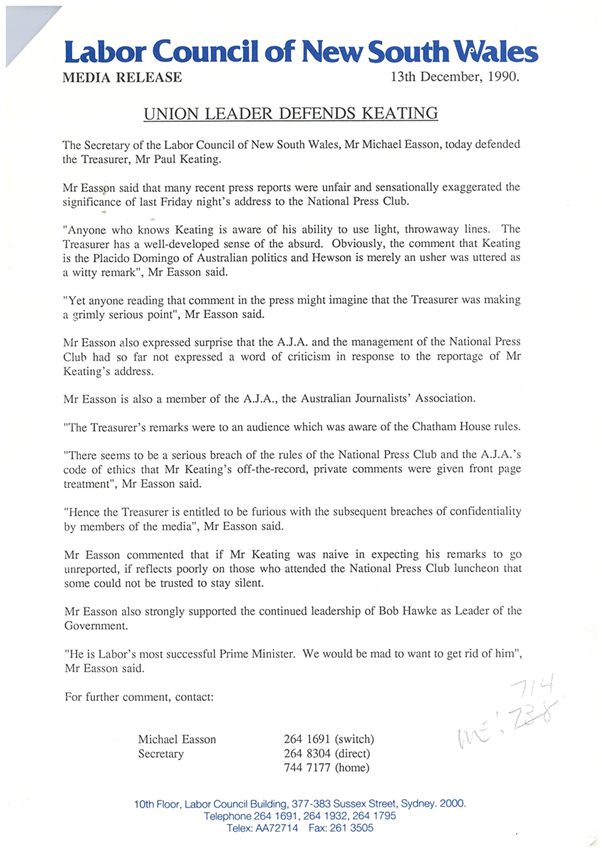

My December 1990 media release, in response to Keating’s Placido Domingo speech, was this:

Media Release

Union Leader Defends Keating

13th December 1990

The Secretary of the Labor Council of New South Wales, Mr Michael Easson, today defended the Treasurer, Mr Paul Keating.

Mr Easson said that recent press reports were unfair and sensationally exaggerated the significance of last Friday night’s address to the National Press Club.

“Anyone who knows Keating is aware of his ability to use light, throwaway lines. The Treasurer has a well-developed sense of the absurd. Obviously, the comment that Keating is the Placido Domingo of Australian politics and Hewson is merely an usher was uttered as a witty remark”, Mr Easson said.

“Yet anyone reading that comment in the press might imagine that the Treasurer was making a grimly serious point”, Mr Easson said.

Mr Easson expressed surprise that the A.J.A. and the management of the National Press Club had so far not expressed a word of criticism in response to the reportage of Mr Keating’s address.

Mr Easson is a member of the A.J.A., the Australian Journalists Association.

“The Treasurer’s remarks were to an audience which was aware of the Chatham House rule.

“There seems to be a serious breach of the rules of the National Press Club and the A.J.A.’s code of ethics that Mr Keating’s off-the-record, private comments were given front page treatment”, Mr Easson said.

“Hence the Treasurer is entitled to be furious with the subsequent breaches of confidentiality by members of the media”, Mr Easson said.

Mr Easson commented that if Mr Keating was naïve in expecting his remarks to go unreported, it reflects poorly on those who attended the National Press Club that some could not be trusted to stay silent.

Mr Easson also strongly supported the continued leadership of Bob Hawke as Leader of the government.

“He is Labor’s most successful Prime Minister. We would be mad to want to get rid of him”, Mr Easson said.

My thinking at the time was that Keating might be in political trouble, and that breaking apart the partnership (Keating from 1990, following Lionel Bowen’s retirement, was also Deputy Prime Minister as well as Treasurer of Australia) was unthinkable.

I had no clue about the deep tensions between Hawke and Keating.

Six months later in June 1991 Keating resigned as Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer to challenge Hawke for the leadership; the ‘Kirribilli Agreement’ came to light, but Hawke won that encounter. On 19 December 1991, Keating challenged again, won, and became Leader of the ALP and Prime Minister.