Published in Troy Bramston, editor, The Wran Era, Federation Press, Annandale, 2006, pp. 209-223.

Part of the culture and practice of NSW Labor is the symbiotic, reinforcing relationship between the leadership of NSW political and industrial Labor. The Wran era, defined by Wran’s period as NSW Parliamentary leader (1973-86), is interesting in throwing light on that dynamic.

This Chapter will briefly discuss the relationship between the Wran government and the Labor Council of NSW, the umbrella or peak body of the unions in NSW. My thesis is that they both needed each other and that the dynamic between them influenced their style and performance. In retrospect, the decade of Wran government was the golden era of NSW industrial Labor measured in terms of union membership, influence and industrial reform. The Wran government began in 1976 with the ascendancy within the NSW ALP of John Ducker (Labor Council Secretary 1975-79) and ended with the election of Barrie Unsworth, a past Secretary of the Labor Council (1979-84), as Premier in 1986.

The Labor Council of NSW

To understand Wran’s interaction with the Labor Council, we must understand John Ducker. The modern Labor Council became very influential in the 1970s with the rise of John “Bruvver” Ducker (1932-2005) and his influence in the Labor Council, particularly from 1967 onwards when he became Assistant Secretary. Ducker was an earnest self-improver, catholic convert, working class leader. Arriving in Australia as an assisted migrant in 1950 aged eighteen and speaking with a thick, distinctive Yorkshire accent, Ducker worked as an unskilled labourer, became a job delegate for his union, became active in the anti-communist fight in the union movement. There he came under the influence of the National Secretary of the Federated Ironworkers’ Association (FIA), Laurie Short, an early mentor, who in 1952 appointed Ducker an official of the Sydney Branch of the FIA. Ducker was later elected as an Organiser for the FIA and became President of NSW Young Labor in the 1950s. In 1961 he was elected Organiser of the Labor Council of NSW (the third most important position), then Assistant Secretary in 1967, then Secretary in 1975. He was elected President of the NSW ALP in 1970 and later National Senior Vice President. Ducker at different points was also Vice President of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU). He became a Member of the NSW Legislative Council in 1972, replacing the long-serving Legislative Council member and former Labor leader Reg Downing, who had served as a Minister in various Labor governments from the McKell era. Ducker therefore spent over a year observing Neville Wran in action in that Chamber. Wran had been selected a member of the Legislative Council in 1970; a year later he was elected Deputy Leader of the Labor Party in that Chamber, then unopposed as Leader in 1972, before standing for election for a seat in the Legislative Assembly in the 1973 state elections. In 1979 Ducker resigned all positions in the labor movement, accepting a position in 1979 (appointed by the Premier) as a full-time member of the three-person Public Service Board of NSW.

The Labor Council leadership, after the great ALP split of 1955-56, largely withdrew from being very active in the Labor Party in the sense of being a decisive influence. They were certainly influential on industrial matters during the subsequent decade of NSW Labor government, but the Labor Council had earlier and traditionally exerted a very strong role within the unions and in the ALP.

That dissipated until the rise of John Ducker and the new Labor Right. Of this group, all men, most were young union officials, in their 30s and 40s, and some younger, from manufacturing and blue collar unions. A majority were catholic, proud of their heritage in saving the NSW party from the damage the split did in Victoria and Queensland, and keen on winning. The core of the group included Barrie Unsworth (ex Electrical Trades’ Union – the ETU, very much Ducker’s deputy as Labor Council Organiser, Assistant Secretary and later Ducker’s successor as Council Secretary), John MacBean (also ex ETU, from the Newcastle region, succeeding Unsworth as Council Secretary), Peter McMahon (Secretary of the Municipal Employees’ Union and Labor Council President), Barney French (Secretary of the Rubber Workers’ Union and Senior Vice President of the ALP, NSW Branch, in the nine years that Ducker was President), and Jim Gibson (Glassworkers).

As a result of many factors, including the changes in the NSW Labor Party machine in the early 1970s and the Whitlam reforms to the ALP from the 1960s onwards (culminating in federal intervention into NSW and Victorian Labor in 1970), the Labor Council leadership played a more dominating role in what happened at Labor Party conferences.

Was the Labor Council a site of factional warfare? Certainly. During the early days of the Cold War, the Labor Council leadership were very important in the ideological battles in the union movement. One of the heads of the Labor Council in the 1940s and later Secretary until 1967 was Jim Kenny. He undoubtedly had a formative role in the creation and development of the ALP Industrial Groups. With the ALP split in 1955-56, the rise of the Left – increasing the vulnerability of the officers in this changed environment – caused the Labor Council officers to be uncertain of their power base. Thus they, for a time became less factional, less involved in ALP affairs, and weaker from the 1956 period onwards.

That changed. The political influence of the Labor Council leadership gradually increased after Labor was out of office from 1965 at the State level. Increasingly the Labor Council leadership played a significant role in modernising the party. With Whitlam’s reforms of the Labor Party nationally at the end of the 1960s, the strongest allies that he had were from the Labor Council leadership and the NSW ALP Right.

In terms of factions amongst the Labor Council delegates, factions were always a bit more fluid than they might appear from the outside. The Labor Council leadership, for example, would pick up votes from certain Left wing unions who secretly supported the embattled Labor Council leadership. For example, Actors’ Equity used to vote that way (or at least certain delegates did); certain people from the miners’ unions agreed never to show up to vote against the Officers. So it was a lot more nuanced than it might appear on paper.

The major factions were influenced by the Cold War, with the traditional communists against the Labor Council leadership and the so-called “Steering Committee” (the official ALP Left) against the Labor Council leadership – but a lot of the old Left unions got on well with the Labor Council officers. What the leadership affectionately called the “red ockers” – the union officials from the Seamen’s Union and what was then called the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU) were against the Labor Council in one sense. But they acted as if they didn’t really want the leadership to fall over and they worked quite cooperatively with the Labor Council leadership. In other words, the leadership knew that most unions, across the factions, regarded the Labor Council as fair, even if it might be in the control of one faction (that being the ALP Right). It was very important for the Labor Council’s credibility to be regarded as fair in the way that it handled industrial disputes, including – as was quite significant until the 1990s – a lot of inter-union disputes over industrial coverage.

The Council officers, until Barrie Unsworth became Secretary in 1979, raised funds for union campaigns. This was important, factionally, in sustaining the Labor Council officers’ power and authority. For example, in 1971 and 1973, Ray Gietzelt’s Federated Miscellaneous Workers’ Union (the “Miscos”) at the State and national level were targeted by the Council’s leadership. Ironically and significantly, the Miscos, covering cleaners and unskilled workers, were one of the growth unions of the 1970s onwards and one of the mainstays of Neville Wran’s industrial practice as a barrister. Wran supported Gietzelt through those times. Indeed, along with Lionel Murphy (barrister, Senator, Attorney General in the Whitlam government, High Court Judge), Wran and his Deputy, Jack Ferguson, were amongst Gietzelt’s closest friends. This is an example of Wran’s independence from the Labor

Party machine and tribal factionalism in NSW. Gietzelt, a World War Two veteran who had trained as a chemist, joined both his father’s company and the Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union when he was demobilised in 1946. Earlier he was briefly a member of the breakaway Hughes Evans Labor Party in the 1940s that was linked to the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), later in the same decade becoming an ALP member and in 1955 won election as Federal Secretary of the Union (serving until 1984). Gietzelt’s support for Bob Hawke at the ACTU Congress in 1969 probably was decisive in Hawke securing the ACTU Presidency (against Harold Souter, the ACTU Secretary, who the Right, including Ducker, supported, though the Labor Council leadership later became central to Hawke’s powerbase).

One consequence of the challenge to the leadership of the Miscos was that Gietzelt purged the union of communists and created a very professional organisation which became the core of the non-communist union Left in NSW and several other States.

A consequence of the Labor Council officers vacating fund raising for union elections was a gradual shift of influence over subsequent decades from the Labor Council officers to the ruling right wing ALP officers in the ALP office, a power shift from the 10th floor to the 9th floor of the Labor Council Building in Sussex Street (where the Labor Council and the ALP offices were located).

The Role of the Labor Council

Perhaps the ideal role of the Council is to create a forum for discussion and the determining of action on the part of the union movement as a whole. Clearly it has a major role in the political process both in influencing legislation and seeking to shape the way that government acts. This includes the appointment of key people with the tribunals and management of organisations like the Workers’ Compensation Court and the Industrial Relations Commission and all the other organisations that would influence the life of the union. So the Council had a very practical role as well as providing a forum for debate and discussion.

The role of all Labor Council secretaries is to talk to everybody and not be part of an insular institution but rather one that has broad connections across the community and the political divide. The primary role is to ensure that workers are looked after.

Ray Markey’s history of the Labor Council, In Case of Oppression: The Life and Times of the Labor Council of NSW, describes the Labor Council as a conduit, a link between unions and the Party. All of the unions, however, had their own links. Many of the unions were affiliated, though some, especially many of the white collar unions, were not. The Labor Council has an interesting role of coordinating a sensible union response between the disparate base of union affiliates. When there were tensions in the sub-factions or between Ministers and particular unions, Ducker would often play mediator, sit down with people, cut through the personalities and get focus on what was important – that is, the core business of dealing with protecting the rights and entitlements of workers.

The relationship with the ACTU has always been a bit ambivalent. The Labor Council is both independent of and yet formally a State branch of the ACTU. Some prefer to see it as a State branch, a subsidiary of the ACTU, and some argue that the Labor Council should be more independent.

Well after Ducker left the scene, in the early 1990s, the Labor Council played a major role in questioning – if not being more effective than that – the amalgamation strategy of the ACTU. Perhaps some unions, like the Nurses’, retained their identity because they supported the Labor Council in that campaign and thought about the consequences of becoming conglomerate health union No 3, or something similar.

The Labor Council would argue that their role as an ACTU State branch is very important, yet that shouldn’t be the limit or the sole identity. From an organisational, effectiveness and public appeal perspective, a viable organisation has character and independence. Interestingly, although in the 1990s, Queensland’s peak union body changed their name from the Queensland Trades and Labor Council to the ACTU (Queensland Branch). They later changed it back to a more local sounding identity. Perhaps the Labor Council, in now calling itself UnionsNSW is giving itself a local brand name. This is more effective and credible than simply being a branch office organisation.

Victory in May 1976

When NSW Labor scraped into power in May 1976, the bet John Ducker placed on Neville Wran becoming leader paid off. In 1973 Ducker, then Assistant Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, the leader of the “NSW Right” and three years in office as President of the NSW ALP, decided that NSW Labor leader Pat Hills had to go. There was a lot of affection for Hills, who had just lost again to Premier Sir Robert Askin in the 1973 State elections. Hills didn’t want to be the only Parliamentary Party Leader since the 1920s not to become Premier. Ducker wanted someone more in the mould of Gough Whitlam. He also knew that the mood in the parliamentary party was shifting, looking for alternatives, and he feared that with the ALP restructuring in 1970, if NSW Labor didn’t produce the “goods”, then the NSW Right’s hegemony over the party would be in jeopardy. So he backed Wran.

So began the myth of the NSW Labor machine backing Wran. Ducker was the key figure in the future premier’s ascension to the Labor leadership. In politics, myths are potent. Some commentators have pointed out that the Left were decisive in getting Wran up as leader; that Ducker’s so-called decisive intervention was worth about four votes in the parliamentary party. The electorate of Bass Hill (a Left wing stronghold) was delivered to preselection candidate Neville Wran in 1973 with the support of Left leader and subsequent Wran deputy and then Deputy Premier, Jack Ferguson. All of this is both partly true and beside the point. Certainly Wran needed support from several wings of the Labor Party to fly. Ducker’s support, though rooted in clear self-interest, was decisive. So it seemed at the time. When Wran became leader, the last thing he needed was commentary that he was a Left leader in antagonism to the NSW Right. Ducker’s support was crucial in blunting such attacks in the media and, indeed, within the party. Party unity, at first uncertain, was achieved. Wran’s appreciation for such support both then and subsequently as Premier was reflected in a comment he made, quoted in Barrie Unsworth’s oration at John Ducker’s funeral in late 2005, that “John Ducker was the most significant Yorkshire man to visit Australia since Captain Cook”.

The victory in 1976 was a close run thing. Originally the party liked to present Wran as NSW Labor’s answer to Gough Whitlam, Federal Opposition leader from 1967 and Prime Minister 1972-75. Both were highly educated QCs, sophisticated in tastes in music and theatre, smooth and polished in eloquence, with a civil libertarian streak, interested in policy and “reform”. Both smacked of a Fabian belief in progress. Wran’s links to the broader labor movement, however, were more extensive (his career as an industrial lawyer ensured that) and his earthiness in judging what went over best with the community made him the less interesting policy maker and the more able politician. That deep understanding of the unions was a key difference between both leaders. In his November 11th 1986 NSW Fabian Society lecture on “The Wran Government and the Whitlam Heritage”, Wran commented that the Whitlam “Government, for all its mistakes and for all the waste and loss of its destruction, will long be a standard for the performance of all Labor governments – State as well as Federal – if they seek to deserve the name of Labor governments of reform”. Though, “it may be true that we are rather readier to acknowledge this in 1986 than we were perhaps in 1976”.

The Whitlam experiment had spectacularly failed with the electorate voting out Whitlam Labor, in a landslide, on 13 December 1975. Runaway inflation and industrial strife at the federal level, partly caused by the oil shocks (steep rises in international oil prices in the mid 1970s) and the collective ill-discipline of the labor movement and the Whitlam Cabinet, caused the public to regard the party as poor economic managers. A more assured leader with deeper links into the labor movement of that time might have curbed the industrial disputation and steep wage hikes characterised by the Whitlam era. The “certain grandeur” of the Whitlam experiment was tarnished.

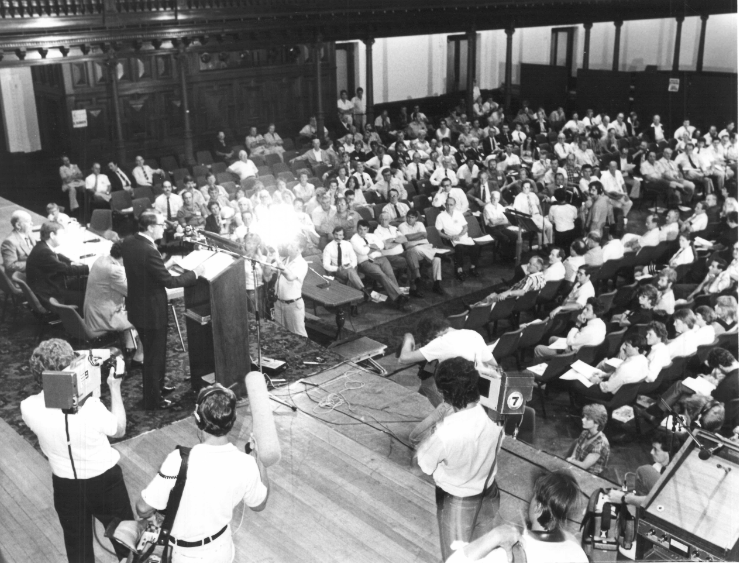

In the 1976 state elections the Wran Opposition turned a potential negative around. Remarkably, industrial relations proved to be a positive in the 1976 State election campaign. Nurses, well organised by the NSW Nurses’ Association, turned up in uniform campaigning on the hustings and in several marginal electorates on polling day. It was a turning point with several white-collar unions, traditionally politically unaligned, siding with Labor. (The Association affiliated to the Labor Council four years later). Concerns about the Fraser government “going too far” on industrial relations changes and rumours about wage indexation’s abolition federally also proved potent in the election. Such factors were highly influential in a close run election, decided by a mere busload of voters. The Labor Council played an influential part in harnessing the political and industrial commentators to report favourably on such matters as well as the essential “responsibility” of NSW union leaders compared to other States. (In those days the “industrial bureau”, a phalanx of reporters from all the major media outlets had offices and reporters in the Labor Council building ready to report “the latest”). Bob Carr, then Labor Council Education and Public Relations Officer (until 1978, then a journalist with The Bulletin magazine, Member for Maroubra from 1983 and Minister in the Wran government from 1984, later Labor leader from 1988 and Premier from 1995-2005), played an important role in that story. As a result, the electorate was prepared to give Wran and his Labor team the benefit of the doubt.

Government

Then came the fruits of government. Arguably, despite the tensions and conflicts that subsequently preoccupied the government, the Wran era was the golden age of NSW industrial Labor, with a steady expansion of union membership, influence and benefits. Access was extremely strong. The government, especially the Premier, would look to the Labor Council for leadership and instead of major industrial campaigns, seek that the Labor Council curb excessive union action. Sometimes the government would look to the Labor Council for ideas, as to what kind of reforms should be pursued by the government industrially. With the exception of the first three months of Wran’s premiership, Pat Hills was Minister for Industrial Relations, serving from 1976 to 1988. Interestingly, immediately after the election, Paul Landa – Wran’s successor as Labor Leader in the Legislative Council and former managing partner of the industrial law firm McClellands (with close ties to the Labor Council) – became Minister for Industrial Relations. In Opposition Jack Ferguson was Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations under Neville Wran. Perhaps as a result of Labor Council entreaties, Landa was made the first Industrial Relations Minister on the government’s election in 1976 – a transitional choice before Hills.

Wran was a barrister who prior to full time politics had a very large industrial practice, so he knew the Labor Council leadership and many of the unions quite well. He therefore had a very good understanding of the role of the Labor Council as, of course, did the next Labor Premier, Barrie Unsworth, a former Labor Council Secretary. In contrast to Whitlam, Wran’s long success as Premier drew from his ties to and understanding of the wider labor movement, including the unions. This gave Wran confidence in picking the right mood in resolving a dispute and to negotiate effectively. Sometimes he advocated changes to industrial relations (such as an integrated national system and a transfer of powers to the Commonwealth) that did not find favour with most NSW unions at the time.

Wran adopted a lot of the social reform agenda to make Australia a fairer, gentler place and more civilised. Some of those ideas (such as Anti Discrimination legislation and Equal Employment Opportunity laws) required the support of the unions. Some of those policies also required adoption in test cases in the NSW Industrial Commission and Wran was conscious that implementation required more than legislative fiat. Consistent with Labor’s philosophy of a “helping hand” to those most in need, Wran’s government provided direct funding support to the Labor Council to implement his government’s social agenda.

From 1976 to 1986, the Wran model in State Labor and State Labor industrial relations came into being. As earlier noted, Pat Hills was Industrial Relations Minister for most of this time. He particularly, despite the events of 1973, got on well with the Labor Council officers. (Particularly it must be noted, after 1979, following John Ducker’s departure). Worthy of note, Wran set up a secretariat in the Premier’s Department to keep him involved and provide an independent channel of advice. The Premier was always an insider on the major industrial relations reforms and challenges of the day. Some significant features of this period included changes at the regulatory level, the promotion of employee participation and funding support for the Labor Council specialist units, which arguably provided workplace support for the government’s social reform agenda. These are each briefly discussed below.

Regulatory Change

The NSW industrial relations system innovated ahead of the Federal system in areas such as redundancy and pay equity. State Labor governments legislated for benefits including shorter hours, annual leave and equal pay. Wran’s industrial relations instincts were broadly in favour of the tribunals developing the living wage and protecting industrial rights.

At the beginning of the 1980s the unions campaigned for minimum redundancy standards. The Commission determined standards covering general redundancies caused by economic conditions and more generous provisions for employees dismissed in company reorganisations. To provide additional assistance, the NSW Government Employment Protection Act enacted at the end of 1982 commenced operations in 1983 with mixed effect. A shorter working week was successfully negotiated in many State agreements, such as a 38 hour week, 19 day month in the building industry, whereas the Federal (Fraser) government tried to prohibit shorter hours negotiations.

In essential industries, Labor argued that better management was the key to avoiding disputes, though the electricity industry in the early 1980s was a fierce battle ground for disputation. In the rail industry in 1981, for example, a $20 industry allowance together with dispute settling procedures incorporating a provision for private arbitration was successfully negotiated by the Labor Council. The procedures also contained a requirement that where negotiations fail the Labor Council is to receive 72 hours’ notice prior to action being taken which would affect transport services to enable the Labor Council to assist in achieving a settlement of the dispute.

Under the Wran government, the major legislative changes in industrial relations included:

1. Anti Discrimination Act (1977). Discrimination in employment on the grounds of sex, race and marital status was made unlawful. Grounds for unlawful discrimination in subsequent years expanded to include age, disability, sexual harassment and family responsibilities as well as race, homosexual, HIV and transgender vilification.

2. Transport industry covered (as independent contractors) in 1979 through amendments to the Industrial Arbitration Act; the following year amendments to regulate contracts of carriage (couriers) and contracts of bailment (taxi-drivers).

3. Industrial Arbitration Act amended in 1980 to provide a standard 12 months unpaid maternity leave. Later expanded to include paternity and adoption leave and, in 2000, to allow leave to be taken by regular and systematic casual employees.

4. Employment Protection Act 1982 created minimum redundancy entitlements for NSW workers under awards.

5. Occupational Health and Safety Act 1983. New occupational health and safety (OH&S) regime introduced, placing greater OH&S obligations on employers and employees and focussed upon injury prevention strategies, employee involvement in OH&S matters and new penalties for breaches of the legislation.

6. In 1984, the Workers’ Compensation Commission was replaced by two bodies, the State Compensation Board and the Compensation Court of New South Wales. The Board took over administrative and licensing functions and the Court continued to exercise judicial functions. In 1984 lay Commissioners were appointed to the Court and given the power to hear cases which did not involve more than $40,000.

7. In 1985, long service leave entitlements for workers increased to two months leave after 10 years of service.

8. Under Wran, the personnel at the senior ranks of the Industrial Commission was drawn from a pool wider than industrial silks. In 1981, Peter McMahon, Labor Council President from 1976-81, was appointed a Deputy President of the Industrial Commission of NSW, the first non-lawyer to be appointed since the establishment of the Commission.

Employee Participation

Consistent with NSW Labor’s industrial relations policies, employee representation was granted on the boards of various State government instrumentalities and authorities, including:

- State Super Board

- Sydney Water

- State Rail Authority (SRA)

- NSW State Dockyard

- The electricity authorities

- Maritime Services Board

- Secondary Schools Board

- Board of Senior School Studies

Directly elected employee representation was legislated for in some of the larger statutory authorities, including Sydney Water, the SRA and State Super. In the early life of the government, Barrie Unsworth was the leading intellectual force for such changes. For nearly a decade, until 1984 he was Chairman of the NSW ALP Industrial Relations and Employment Committee which recommended such policy changes to Conference in the mid 1970s.

The Labor Council Specialist Units

After the Wran government was re-elected in a landslide in 1978, state government funding support commenced for the development of specialist units within the Council, including:

• Drug & Alcohol (1978)

• Arts and Cultural Activities (1979)

• Ethnic Affairs Unit (1978)

• Women’s Advisory Unit (1980)

• Occupational Health and Safety Unit and Social Welfare Unit, absorbing the Drug & Alcohol Unit (1980)

In 1982, funds from the Premier’s Department were made available to the Council for the employment of three project officers to deal with child care services and family day care. In the same year, funding was made available for the employment of a research officer from the National Employment Strategy for Aborigines, provided largely by a grant from the Federal government. Funding for the restoration of heritage trade union banners (a Bicentennial project) was also made available at this time.

Labor Council research officers were busy attending migrant workers’ conferences; organising interpreters and translators for union meetings and Court appearances, engaging in adult education programmes (including with the Trade Union Training Authority), negotiating child care industrial agreements and pioneering child care at factories and workplaces. The Labor Council Women’s Advisory office would tour NSW country and metropolitan areas in a Datsun van equipped as a mobile information unit.

Such activities were both supported by, and added grass roots substance to, the Wran government’s reformist zeal. Consequently, the Labor Council appeared progressive and appealing to many of the white collar unions which affiliated to the Council throughout the period that the Wran government was in office. The typical pattern was that before a given white collar union affiliated to the ACTU nationally (the largest private sector white collar unions were outside of the ACTU at this time), the NSW branch affiliated first to the Labor Council. Unions such as the Bank Employees, the AMP Staff Association, the Insurance Union, the Nurses, the Professional Engineers and many others did so. By the early 1980s the Council had affiliated over 120 unions covering nearly 900,000 workers. It was the high point of union membership in NSW and the first time that the Council could claim to be representative of the entire workforce from blue collar to professional employees.

Overview

Arguably there were three phases of the government’s life. The first phase was 1976-78, the first term of the government; followed by the period 1978-84, which saw John Ducker’s replacement in 1979 with Barrie Unsworth and the election of the Hawke government in April 1983; then the final phase, from 1984-86.

The one-seat majority government adopted a cautious approach to governing in its first term; the landslide electoral victory in 1978, then 1981, led some unions and the Labor Council leadership to be more aggressive in pursuing industrial objectives. In the latter period, the Council opened a northern regional office (with some government support), partly to deal with the Hunter Valley employment boom, including the development of the Tomago alumina refinery and the construction of several new power stations. But the labour market began to affect the industrial relations climate. Unemployment rose from 6.3 per cent at the end of December 1981 to 7.9 per cent in November 1982, and over 10 per cent by 1983.

An area of tension opened up in 1981, following the retirement of Sir Alexander Beattie as President of the NSW Industrial Commission. Overlooking Justice John Cahill, a son of Premier J.J. Cahill and a well-respected senior member of the Commission whom many considered a “safe choice”, the Labor Council supported Justice James (Jim) Macken as Commission President. Wran overruled his minister’s advice and selected Bill Fisher, then a QC with a busy practice from Wentworth Chambers, as the new President. At the time, Wran privately expressed opposition to a “NCCer“ (Bob Santamaria’s National Civic Council) getting the job. Macken had once been an active member of the DLP, though by this time had support across the union political spectrum as an innovator and union friendly judge. This defeat of the Labor Council officers’ recommendation led to tension between the Council and the new Commission President in the first few years. At one point the splitting of the Commission into a legal court and a Commission of arbitration was pursued but brushed aside by the Premier.

In 1982, the unions clashed with the government over the retention of specialist services and hospitals in the government’s so-called “Beds to the West” campaign (i.e., to shift services away from highly serviced inner Sydney to the western suburbs, where the population growth was highest). The Labor Council claimed that the implementation was poorly considered industrially. The then Minister for Health, Laurie Brereton, would make announcements about big changes to hospital organisation, not consulting the unions who had concerns about loss of jobs. So, there were some significant industrial campaigns that caused the Wran government to clash with the unions. Sometimes this had the unfortunate effect of the unions looking defensive, even reactionary, as if the unions would oppose the more equitable distribution of resources, the reallocation of resources to Western Sydney. The real dispute was about consultation and implementation.

In 1983 the Hawke government was elected on a platform of introducing a wages and prices Accord. The Accord proposed the reintroduction of a centralised wage fixing system based on the maintenance of wage and living standards by adjusting wages to movements in the consumer prices index, the introduction of a universal health care system and the establishment of a Prices Surveillance Authority, among other things.

In the third phase of the Wran government, the social wage and industrial relations priorities of the Federal Labor government and the ACTU became increasingly important. For over a decade the Labor Council, funded in part through successful media interests, such as Radio Station 2KY (owned from the mid 1920s), had been comfortably better resourced than the national body. Gradually, national union affiliates under the Hawke then Keating governments conferred significant power and resources to the ACTU.

At the end of his government, Wran was feeling worn out and he had suffered the humiliation of a Royal Commission. In 1984, Barrie Unsworth became a Minister in the Wran government. When he announced his retirement as Labor Council Secretary, he commented that, “The significance of my decision was that E.J. Kavanagh, the first Secretary to serve simultaneously as a Legislative Councillor and Labor Council Secretary, ceased to be Secretary in 1920 upon his election as the Upper House Labor Party Leader, and I hoped to repeat history in that regard. Also I felt the need to bring to the NSW government a strong point of view reflective of the aims and aspirations of a trade union organisation, the Labor Council, which founded the Australian Labor Party 92 years ago.” John MacBean (Secretary from 1984 to 1989) succeeded Barrie Unsworth.

Following the defeat of the Unsworth government in 1988, the relative importance of Wran and Labor governments to the Council and the comparative radicalism of encouraging employee representation became more readily apparent. The new Coalition government led by Nick Greiner dismissed the Labor Council and union (and phased out all of the employee elected) representatives from boards of statutory authorities, apart from the State Super board. (In the Greiner era, the Legislative Council refused to support the government’s amendment to abolish that position). They also cut off funding for various positions in the Council. That had a big financial impact on the Labor Council.

Comment

Some critics talk about the Labor Council and unions acting as a block against the rest of the Party in terms of social reform. This is not borne out by the experience of the Wran government. Hard reforms in the railways, reform of public administration and workers’ compensation were tackled by all of the governments of the Labor persuasion, usually with the sympathy of the Labor Council officers.

The Labor Council experienced difficulties with both Labor governments and Coalition governments. With a Coalition government, there is always a hostile outlook; sometimes, for the Officers, the difficulty in dealing with Labor governments is one of being alleged to be too far colluding with the government or too understanding towards them in attempting to coordinate union responses. With a Labor government, criticisms can sometimes be made that the Labor Council is too weak when the Labor Party isn’t acting fully in the interests of the union workplace. Sometimes the Labor Council is criticised as putting a friendly spin on government policy to sell a policy.

In contrast, however, is this author’s knowledge over thirty years of the ethic, ethos and policy of the Labor Council at the leadership level. All have tried to act in what they believe to be the best interests of the union movement. Normally that coincides with the Labor Party’s position, and that Labor Party position is often influenced by the Labor Council. But often action is taken that is very testing of relationships. The unions always come first. Sometimes the Labor Council Secretary has to burn up a lot of goodwill with affiliates in order to get an idea across the line.

This occurred with the Workers’ Compensation reform during the time that Barrie Unsworth was Premier and John MacBean Secretary of the Labor Council. In more recent times, John Robertson burnt a lot of goodwill with the Labor Party and the government with his campaign on Workers’ Compensation reforms under the Carr government. They were different disputes. It is clear from such instances that Labor Council officers do not slavishly follow the Labor Party’s position, or think that their job is to follow party edicts. They will consider what is in the best interests of the union movement – first, second and third. Such leadership involves not merely reflecting what people believe, but also exercising leadership in judgment.

Having Labor in office is very important for the unions. There’s a lot of support from a Labor government. Especially over the last thirty years, the Coalition parties have become much more anti-union. With the end of the Cold War, a lot of conservative employers have become more overtly anti-union. Some of them used to think that a few of the anti-communist unions were a good thing, but that has changed dramatically.

Unions have civilised capitalism and in part are the victims of their own success in the sense that they can look around and the world is a lot fairer than it used to be. In order to push and exercise power, most employers and modern management theory is about motivating people and keeping them motivated. That is certainly true for middle class workers, but less so for disadvantaged workers and that’s where the union movement’s greatest role is – to protect the more vulnerable workers. In coalition with the Labor government, unions co-ordinated by peak bodies such as the Labor Council of NSW, can help workers and their families with welfare support that complements the industrial conditions that might be won.

As indicated herein, the Wran government saw no transmission line of policy origination in Sussex Street and implementation in Macquarie Street. Rather, the process was demanding. Possibly because of Wran’s independence, depth of industrial relations expertise and wide contacts within the movement, that process was particularly interactive. Pat Hills, as Industrial Relations Minister, became the conduit to the government of the Labor Council’s views.

How does the peak union body exert influence over the government? Primarily this is achieved through persuasion, arguing as the case might be that a particular proposition is a reasonable course of action and that it is the right thing to do. To be effective, the Council Officers have to empathise with the dilemmas and challenges of the government or of the Labor Party dealing with the challenges of the day. It is not just “bending” – the government gives a lot and it’s a dynamic process when in government.

NSW has led the rest of the country in securing wage increases. Protection in health and safety and workers’ compensation is arguably strongest in the foundation State. The Wran government was good for the union movement in NSW and good for the Labor Council. They stood to gain working with each other.

Postscript (2015)

I am not sure what was published compares with this version; this was submitted in revised form a tad late.

Wran was the best politician I ever saw in action.