Published in the Australian Left Review, Vol. 1, No. 140, 1992, pp. 30-31, http://ro.uow.edu.au/alr/

One can define the Left as the non-conservative forces in society; one can also define it more narrowly as the Left traditions within the labour movement. It is apparent that there are various traditions that make up the Left of the labour movement in this country. Various of those traditions are alive, and some, I think, are dead. Yet on the various problems and challenges facing the labour movement today, it seems to me disturbingly evident, as someone active both in the Labor Party and the trade union movement, that there is hardly any debate going on. Indeed, a lot of the debate that does take place seems to me to be fairly sterile and mindless. For example, the debate about whether or not Australian Airlines should be privatised largely turned on one’s attitude to the traditional goal of public ownership. The shibboleth of public ownership for its own sake became a key issue among many of us, rather than asking the important questions, such as: what should be the role of government, what are the principles that we should be seeking to have achieved through the labour movement, and does Australian Airlines play a role in that?

What kind of forum is there to debate issues within the labour movement? Most Labor Party branches are mindless events. There is very little debate about policy, and no-one seems to be greatly interested in changing that. The trade union movement has similar problems. Here we have to confront the prospect of a change of government. One of the facts facing the trade union movement this decade is that Dr Hewson or another conservative leader will become prime minister. If it isn’t the next election, or the election after that, one day the conservatives will win. And when they do, they will be more vicious and determined in their approach to the trade union movement than ever before.

Of course, we are attempting to answer that problem by award restructuring, by the amalgamations strategy and the like. Yet it seems to me we ought to have a number of reservations about that strategy. I worry, for instance, that we are creating a more bureaucratic trade union organisation, one which won’t be responsive to many of the wishes of rank and file activists. That applies whether the amalgamated union is supposedly rightwing or leftwing. It will apply when ADSTE [the Association of Draughting Supervisory and Technical Employees] merges with the metalworkers union and 40% of the ADSTE members no longer choose to join the union. It will apply when the Australasian Society of Engineers (ASE) joins with the ironworkers to form FIMEE [Federation of Industrial, Manufacturing and Engineering Employees], and 30-35% of the ASE’s members just disappear. And I worry that we do not debate many of these issues in a serious way within the trade union movement.

Finally, there’s often a tendency for those of us involved in labour politics and the trade union movement to demonise one’s opponents, and to eulogise the kind of traditions which you see yourself as belonging to.

Yet a labour movement worth its salt is a labour movement that is tolerant of various traditions, and tolerant of the various ideas which are part of that tradition. A person I’ve often regarded as a central figure within the labour movement is Dr Lloyd Ross, after whom the Lloyd Ross Forum was named. Lloyd Ross was a communist; he wrote a book on William Lane and Lane’s trip to Paraguay. Later he became active in the Workers’ Educational Association; later again he became the secretary of the Railway Workers Union, and after leaving the Communist Party during early part of World War II, in government in the ministry of postwar reconstruction, he worked with Ben Chifley and John Curtin. In the early 1950s, he came back to the union and became a Grouper. At the end of his career he argued that the best person to succeed him as secretary of the Railways Union was a man who happened to be a member of the Communist Party. Ross was a person who no-one in the labour movement could quite understand. He’s someone with whom I have a lot of sympathy.

It seems to me that what Ross represented was the belief that the labour movement has a multitude of traditions, and many individuals with strengths and weaknesses, and that the important thing within the labour movement is to try to nurture that, and to try to encourage debate and understanding of the many issues with which we have to grapple. There are no definitive answers to the problems we face. If I were to sum up what I believe in, I would find it very hard to put it in terms which would label me a leftwinger or a rightwinger. In different respects I am a social democrat, a liberal, a conservative, in the various issues I confront. I think in that respect, I am part of the tradition of the labour movement and its principles. To me, our historic role, whether as part of the Left of the labour movement, however that might be defined, or as part of the movement’s centre or right, is to civilise capitalism. I think that is an important task; it’s sometimes been an heroic task for many of our forebears. It is a never-ending task, and one which I think we have a duty to share.

Postscript (2015)

This article was based on a transcript of a recording of my remarks on the night of an event, which featured other speakers, including Peter Baldwin MP, who was then the federal Minister for Social Security and member for Sydney, and Sue McCreadie, the then economic research officer for the Textile, Clothing and Footwear union, and a member of the Australian Left Review (ALR) editorial board.

I wish I had been more coherent.

One point I wanted to make is that ideas of Left and Right in the ALP could be stultifying terms.

The ALP Right had stood for certain things and in opposition to others. Mainly, this was for the idea of civilising capitalism, through small and sometimes ambitious measures, in the attempt to improve the lives of real people. That quest is glorious. Part of the organisational coherence of the ALP Right was opposition to communism. Sometimes this was based on religious conviction (Catholics, for example, having a deeper appreciation of communist suppression of religion than some other denominations.)

The ALP Left, like the ALP Right, was an amalgam of forces and tendencies, ideologies, traditions and outlooks that coalesced around positive and negative ideas. For many, Marxist critiques of capitalism were influential, a more benign view of state control and government “interference” in the economy was entertained by members. Some had sympathy for the Soviet Union’s so-called ideals, most seeing, however, the flaws and evils. There was almost a countervailing suspicion of the United States, muddled thoughts about imperialism and a quest for “independence” in Australian foreign policy.

Summarising the two major tendencies this way begs many points of nuance, clarification, and elaboration. And of consideration of real people. Plus, reflection about the fluidity of ideas, overlap of views, and creative formation of policy.

Lloyd Ross struck me as an exemplar of what I had in mind, a person not always easily categorised, who never stopped thinking about translating Labor ideals to worthwhile reform.

Additionally, front of mind were the two people I was debating with.

Baldwin was clearly not a Marxist or a supporter of the Gietzelt Marxist Left tendency of the NSW ALP Left. I did not know him well, but back then he struck me as a middle class radical, probably radicalised by opposition to the Vietnam war, socially liberal, and a rebel against the soft authoritarian style of the NSW ALP Head Office. So far as I could tell, his leftism in those ministerial positions he held, in employment and educational services, higher education, and social security, marked him as someone in the ALP mainstream. In really existing political outlook and action, he could fit into either faction.

Sue McCreadie, I knew less well, but I saw that however she got there ideologically, she was a practical campaigner for wage justice and seeking to lift the social condition of poor, often exploited, mostly overseas-born workers in a tough and declining industry.

With the three people leading the discussion that night, there was so much more which united rather than divided us.

That, partly, was my thinking.

The year I spoke was also in the aftermath of the early years following the collapse of European communism. I could foresee that an important aspect of the idealistic organisational impulse of the traditional, main NSW ALP factions would diminish. By that, I meant that anti-communism was once a reason to get active, take sides, and battle the enemy. But now that could no longer be the case.

On the left, the Gietzelt grouping strove to maximise support for what might be called a soft-left, neo-Marxist viewpoint, broadly in line with the more liberal CPA thinking associated with the Aarons family in NSW.

Within the left, I also saw that people like Baldwin, John Faulkner, and Rodney Cavalier, were opponents of Gietzelt and were anti- any CPA influence in the ALP.

All this was diminishing before my eyes, rapidly turning to irrelevance.

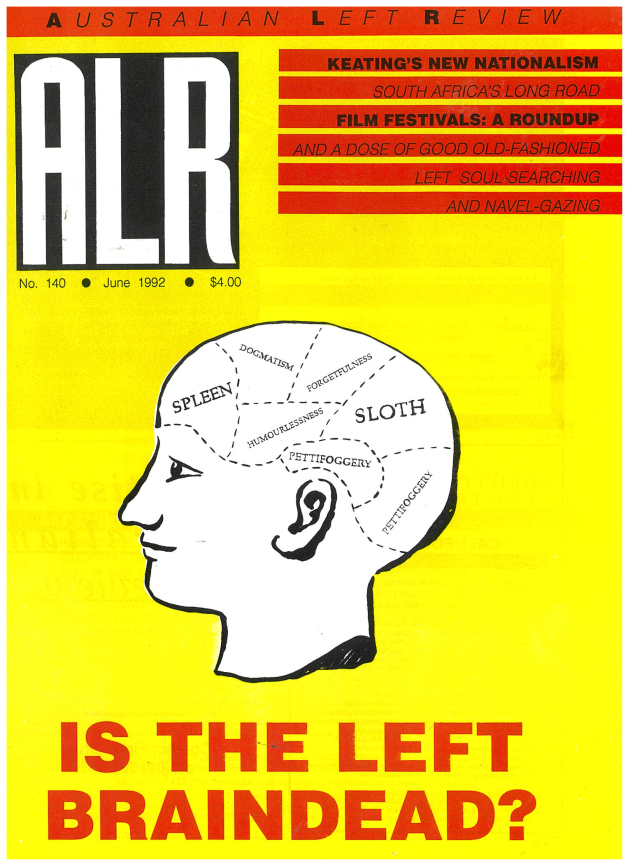

So, I wanted to invite my audience to think in unconventional ways about factionalism. The left would be brain dead if it did not revisit past assumptions and move beyond Cold War thinking.

The example of Lloyd Ross was to cite someone who always saw himself as a radical, whose allegiances shifted depending on the circumstances of the day, who was clearly impressive, driven, sincere, creative in fighting for respect for the workers he represented, and in pursuing bread and butter improvement in the lives of the railway workers he served over many decades in the union movement.

Where I was muddled, was in the references to Ross’ engagement with communism, roughly as a secret CPA member from 1935 to 1940 or ’41, while retaining ALP membership, and then in 1969, when he backed a CPA member as his successor as secretary of the Australian Railways Union, NSW Branch. Ross came to see in the early 1940s onwards the pernicious influence of communism. His eloquence and brilliant writing skills were to the fore in opposition to subservience to pro-Moscow communism and for the application of Labor ideals to the creation of a fairer, post-war world.

At the end of his time in the rail union, Ross was overwhelmed due to the tragic death of his son, David; exhausted by a life of emotional, intellectual and organisation battles in the union, and in the context of the industrial relations system; in all the burdens and demands on his busy life. He failed to prepare or groom a successor or to have some capable colleagues who he could say were blooded in the traditions he had long espoused. So, in retrospect, his support for a candidate who happened to be a member of the CPA (in this particular case, a person independent of Moscow and more influenced by the more liberal or independent strand of thinking within the then CPA) was actually a sign of defeat, despair and depression. Laurie Short told me that Ross never recovered from the death of his son, David, who worked with Short in the Research Department of the Federated Ironworkers of Australia.

On a separate theme, in my speech I referenced various union amalgamations. There had been a lot of corridor speculation about the factional implications, in the main, how much this might increase the influence of the left in the Australian labour movement.

I asked whether we had thought of the consequences, whether inadvertently in some industries and unions, we were weakening ourselves, more narrowly defining the spheres of union organisation.

All in all, I wanted to think aloud on my feet about contemporary challenges and how weak past factional perspectives might be in envisaging the future.