Published as the ‘Foreword’ to Susanna Short’s Laurie Short, A Political Life, Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, 1992, pp. v-xvi.

I can remember sitting down in 1977 in Laurie Short’s office at 188 George Street, Sydney, and discussing the origins and development of the Trotskyist movement in Australia in the 1930s. At the time I was researching the social philosophy and political ideas of Professor John Anderson — someone Short knew in the heyday of anti-Stalinist Trotskyism. As a precocious teenager, Short attended the inaugural meeting and played a large part in the formation of the Trotskyist Workers Party (Left Opposition) of Australia. Short struck me as well read, articulate — even dynamic: someone who would be interesting to know and to learn from.

At the time I first met Short I had joined the NSW ALP Right but had reservations about the faction. Short struck me as someone who was forceful, independently-minded, and seriously interested in ideas. Perhaps if the NSW ALP Right were a bit more like Short that grouping would be worth defending without much reservation. All political movements are coalitions with various elements, tendencies and sub-groups, frequently contesting for influence, power, ideas and the spoils. Democratic politics, in Harold Lasswell’s famous phrase, frequently is a matter of who gets what, when and how. But it is also a contest involving ideas. Short, within the Australian Labor movement, was not only a player but also a thoughtful contributor to the arguments about what the fight was all about.

Over the next twelve months, Short and I regularly discussed current events and political ideology. My requests for meetings were invariably accepted. These meetings became easier when, in early 1978, I began work with John Brown, elected as a member of the House of Representatives in late 1977. Brown’s office was located in Chifley Square and therefore a mere 5 minutes walk from Short’s office. A fascination with the Communist world interested us both. Short once told me that his favourite description of the Soviet Union was a phrase of Max Eastman’s which referred to Soviet despotism as bloodstained and iron-heeled.

On another occasion Laurie quipped that he never wanted to visit a Communist country. Now it is doubtful that he will ever get the chance. That world is vanishing. At the time of writing, the Communist world has almost disappeared from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

What interested me most about Short was not only his political beliefs and his understanding of political events, but also his style as a union leader and his achievements in the Ironworkers’ Union. He was tolerant of others and understood the ideals and motives of many of his opponents. In the early 1980s he would see Jack Mundey in his office and discuss industrial and political events with him, a Communist and ex-union official formerly with the Builders’ Labourers’ Federation in the 1970s. Short attacked the BLF for expelling Mundey from membership in the union and preventing him from gaining employment in the building industry. Short was publicly critical of the rest of the union movement for silently accepting or acquiescing to this outrage. Short, as someone unjustly expelled from the FIA in the heyday of Communist control, was sympathetic to Mundey’s plight. Courts had ordered the BLF to issue Mundey with a BLF union ticket, but none was issued. Years later some of those critical of the corruption exposed in the BLF conveniently forgot much about the days when they were palsy-walsy with Gallagher.1

The modern generation is apt to forget how hard, ruthless, extreme, and sincere many of the leading Communist union leaders of the 1940s and 1950s were. The character of those men (there were hardly any women) is clearly conveyed in the pages of this biography. In the 1970s, 1980s and the 1990s, more usually than not, Australian communists were, and are, gentle, sensitive souls more interested in green issues than the dictatorship of the proletariat. In Geraldine Doogue’s programme on Australian communists broadcast on ABC television in 1990, Laurie Short is filmed saying that Jack McPhillips — the CPA leader of the FIA at the time of Short’s takeover — would have been signing death warrants with both hands at once if he had attained high office in a Bolshevik Australia. He wasn’t joking. That programme, as well as this book, are reminders that the Australian Communist apparatchiks of the 1940s and 1950s were ugly manifestations of Stalinist toadying and mimicking.

The kind of person Thornton was remains a mystery. How close was he to drifting away from the Party? His expulsion from the Party in 1932 apparently left him desperately keen to return. In the 1930s and 1940s he built the FIA into a very powerful industrial force. By the mid-1940s his talk about co-operation between labour and management suggested he had mellowed. It was similar to what the American Communist Earl Browder was then saying. When the line changed, so did Thornton. Fists punching the air, super-militant talk — and action — characterised some of his performances later in the 1940s. In his sweeter period, his speeches knew no stopwatch. Once, in 1944, Thornton delivered a two hour lecture about the need for greater co-operation between managers and workers at a Balmain ironworkers’ branch meeting. This must have made him enemies for life. Two hours! Even the most steadfast supporter must have felt weary after such a harangue from the National Secretary. Two hours! Short couldn’t have wished for better opponents. Only a man touched by golden oratory or megalomania could talk so long.

What were Short’s achievements? One was to fight and fight again for the ideals that he believed in. Those campaigns became more credible the more he shed Communist and Trotskyist ideological views. For example, the Balmain Trotskyists were a bit bonkers about the war effort. Communists, prior to the German invasion of the Soviet Union, liked to describe World War II as just another imperialist war. However, when Uncle Joe was under siege, the communists in Australia turned into super-patriots. Of course, at this time there was the very real danger of the Axis powers winning the war. Within the union movement, industrial conflict was frowned upon by CPA leaders. Nothing should upset the war effort. But the Short and Origlass forces refused to be cowed by the intimidatory warnings of FIA officials that their industrial campaigns were undermining the war effort. In the actions of Short and Origlass there was a mix of ideological obsessiveness and fussiness about not letting the boys forget the wrongs of the capitalist system, and teasing of the FIA leadership. In wartime, democratic rights should not be whisked away – especially in a war against totalitarianism. But the Trotskyists’ general attitude to and behaviour in industrial conflict in the circumstances of the times, whatever the communist excesses, was over the top.

One point that struck me in this book was the reference to the many obscure but interesting characters on the Sydney political stage. One such character was Jack Sylvester. In the 1930s, Sylvester was an active leader in Sydney’s unemployed workers’ movement, a founder of the Sydney Trotskyist party and part-time Domain orator. How close was Short to being another of Sydney’s eccentric extremists, parodying and provoking his opponents, but condemned to a minor, oppositionist and defeatist role?

In one sense, history was kind to him. The communist offensive against the Labor governments in the late 1940s contributed to the anti-communist tide. The ALP industrial groups and the Movement were important factors in providing the resources, legitimacy and momentum for the anti-communist attack. I doubt that Short would have prevailed in the late 1940s and 1950s but for that network of support which organised to defeat communist influence in the union movement.

Although it is customary nowadays to emphasise the pernicious consequences of the vicious factionalism which characterised the ALP and much of the Labor movement in the early and mid-1950s, there were other sides to the contest for power. One result was that many able people – from within union ranks and outside – seriously participated in the activity of unions. Many new members were recruited. Many activists were developed in the course of the struggle.

In their history of electoral contests in the International Typographical Union (which, despite its name, only existed in North America), Lipset, Trow and Coleman comment:

The sheer existence of a two-party system provides one of the principal opportunities and stimulations for participation in politics by the members of an organization or community. If one compares a party conflict to contest between different athletic organizations, one can see how this process operates in areas other than politics. In a city which has two baseball clubs, or two high school football teams, many individuals who have no great interest in sports are exposed to pressures to identify with one or the other team by the fans of each one. Such identification, once made and reinforced by personal relations with committed fans, seems to lead many people to become strongly interested in who wins a given sports contest. Political identification, while more complicated, nevertheless takes on some of the aspects of team identification. Political parties, once in existence, attempt to activate the apathetic in order to keep alive and win power. This process undoubtedly leads more people to become interested and involved in the affairs of the community or organization than when no political conflict exists.2

In similar terms, it can be argued that the battle within the FIA through the 1950s and the ‘two-party’ contests for leadership, assisted in the recruitment of new members and the development of corps of enthusiasts for the combatant sides.

The contest for control was not an uncomplicated good. It is rare that the language, tactics and temperament of union election contests are conducted with the elegance of Fabian Society pamphleteering. In the 1950s the issues went beyond obliterating Communist Party control of unions. The contest within the ALP and unions became so fierce as to be a battle where rival factions would demonise their opponents in pathological terms. Perhaps this observation merely describes what happened rather than explains the underlying reasons for this happening. This book provides many insights into the thoughts and behaviour of some of the leading protagonists in political and industrial Labor. The climate of the times, the personalities involved, the rolling effects of unintended consequences, the thirst for power and ideological influences all contributed to the wrecking of Labor unity in the mid-1950s.

Ironically, Short was not wholly trusted by his Movement supporters. Santarmaria’s 1953 ‘Movement of Ideas’ speech questioned how reliable allies like Short and Lloyd Ross would be in the years ahead. This speech, a transcript of which exists in the Australian National Library (in the Lloyd Ross Collection), is a key document in explaining Santamaria’s motives and suspicions in the period prior to the ALP Split.

Santamaria’s lecture was, in part, an analysis of the threat posed by what he called the ‘third force’ – the non-communist, anti-Grouper types (many of whom Santamaria regarded as having affinities with the Bevanites in Britain) – to the gains made by Movement supporters in the ALP in the early 1950s. Referring to the views of J.P. Ormonde, a Catholic opponent of the Movement and later a Labor Senator, Santamaria states:

Next, within the Labor movement we have got to prepare now, and we haven’t done it so far, a strongly argued case in favour of the ALP Industrial Groups; you have got to answer the Ormonde argument that the Groups threaten the structure of the Labor Party. Unless that is done and that argument is propagated everywhere, you will find that the Groups will be subject to constant attack, just as Lloyd Ross has been whittled away from them, so you will find in time the danger of the Laurie Shorts and Neillys and others being whittled away.3

The danger of the emerging ‘third force’ in Australian Labor politics was revealed, according to Santamaria, in the contests for positions in the 1953 Labor Council of NSW elections. The then Assistant Secretary of the Electrical Trades Union (NSW Branch) and President of the NSW Industrial Groups, J.P. Keenahan, challenged Jim Shortell of the Pyrmont Sugar Workers’ Union for President of the Council. Shortell was supported by the Labor Council officers and most of the Movement’s supporters in NSW. Ross was sympathetic to Keenahan who was influenced by Ross’ ideas on worker participation and joint consultation.

Ross argued that: “In the characteristically muddled way in which such contests are often waged it is suggested that Keenahan — who is president of the industrial groups which fight communism in the Unions — is a communist in disguise, a near communist, an unconscious communist or at least will get the communist vote.”4 Ross stated that the split in the ranks of the moderates occurred “mainly because there is another group which now rejects the view that anti-communism is an all-sufficient guide in deciding industrial politics.”5 Keenahan lost the ballot and shortly afterwards resigned from the position he held in the ETU and completely dropped out of a leadership role in union affairs.

That contest highlighted a number of things. First, the Industrial Group base was much more diverse than is commonly credited; second, Short and (especially) Ross were not wholly trusted by the Movement leaders. In one sense this was understandable. When Santamaria delivered his speech, Short had only officially broken with the Trotskyists four years earlier. How stable was his new-found commitment? But in another sense Santamaria’s speech revealed a paranoia about wolves in sheep’s clothing. Eventually many Movement members and supporters would themselves become victims of the intolerance and narrow factionalism that characterised so much of Labor politics in the 1950s.

Hence it is ironic that Short is sometimes described as a ‘Movement hard-liner’ or as a ‘Movement character’.6 He was never a member of the Movement. In the aftermath of the Split, Short stuck to Labor. He fought against the affiliation of the Victorian branch of the union to the DLP. Sometimes, as the ALP split unfolded, there was rancorous tension between Short and Harry Hurrell, the National Assistant Secretary of the FIA. (In fairness to Hurrell, it should be noted that he was a hard-working and brilliant industrial negotiator. There were periods of tension between Short and Hurrell, but also – and mostly – long periods of fruitful collaboration.) Obviously, as for many Labor moderates, what happened in the ALP in the mid-1950s sickened and appalled Short. It was brutal, hurtful and vicious. Allies of Short in the Labor movement, especially in Victoria, were flung out or left the party. Dr Evatt’s behaviour, as Neville Wran once observed, was a big factor in the devastation of the Great Split that should not have happened. In his Foreword to a reprint of Evatt’s biography of Holman, Wran wrote:

… it is difficult to see that there was any inevitability about the Split of 1955. Much more than in 1916, the spirit of disinterestedness was absent. In other words, splits may be inevitable and may even be necessary if deep and insoluble issues of principle arise, although skilful leadership should always strive to the limit to avoid the final tragedy. But splits which involve no fundamental issue of principle, but merely reflect an excess of factionalism, can never be condoned or justified.7

Evatt’s leadership not only contributed to the final tragedy but also initiated and worsened the disaster.

For a brief time at the height of the Split, according to Jack Kane, Short stated his private support for an ALP breakaway in NSW.8 But in the end he followed a different course. Because Short supported the stay in and fight, or ‘live to fight another day’ elements within the ALP, he helped to ensure that Labor at least remained strong in NSW. Wran acknowledged this in his remarks at the 1982 Testimonial Dinner in honour of Short, mentioned in this book, wherein he doubted that he would ever have become Premier of NSW but for Short’s decision to stay with Labor. Was Wran right? Wran became Premier in 1976, twenty years after the Split, but his win in the election was extremely narrow – a one seat margin. A weaker Labor Party might have failed to win many of the marginal electorates.

Wran’s comments asserted what everyone involved in politics knows to be true: political success depends not only on the chances and initiatives of the present, but also the foundations, ethos, and actions of the past. Just as Neville Wran observed in 1982 that he would not have become Premier but for Short and his allies’ decisions to stick with Labor, a similar observation can be made by the author of this Foreword. Just as Short was assisted by the leaders of the Labor Council of New South Wales in his battles with the FIA hierarchy in the 1940s, so too did his decisions in the mid-1950s contribute to the continued survival of moderate Labor within the Labor Council of New South Wales.

One of the interesting points drawn out of this biography is that the battle to win over the FIA from the communists was a lonely campaign marked by weird twists of fortune, but also involving skilled organisation, and helped by over-reaction by the communist leadership and ballot-rigging favouring the incumbents on a huge scale.

Commenting on the successes in 1950 of Group candidates in the Newcastle branch of the FIA, Lloyd Ross stated: “Apathetic and often politically cynical workers have been aroused to take action to defend their views, especially when their communist officers have over-reached themselves. The anti-communist revolt in Newcastle has been built into an organisation, partly because there existed a group of local advisers, partly because they achieved an early success, partly because circumstances were favourable.”9 Such success didn’t merely occur because of favourable circumstances. A huge organisational effort was required. ALP endorsement was not sufficient to enable Group candidates to achieve certain victory — as results in 1950 in the Sydney Boilermakers’ Union indicated: “The biggest weakness in the revolts is the absence of an ideological inspiration or understanding, as effective as that which keeps the communists fighting against great odds.”10 This problem continued to be a weakness in the Groups’ battle for control of Australian unions and this weakness also called attention to some of the problems facing the ALP in the 1950s. New thinking about the directions and priorities of Labor governments was urgently required. The Split postponed that fresh assessment for a decade.

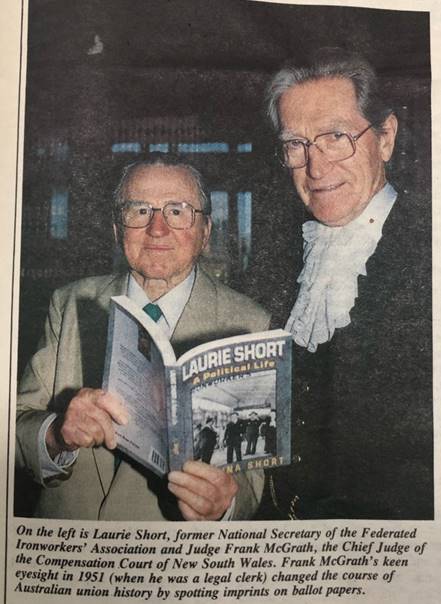

Sometimes I’ve wondered about Judge Dunphy’s decision, after an exhaustive, eighteen-month long court battle, to award Short the Secretaryship of the union in 1951. Was Dunphy biased against the communists? Should he have called for a fresh ballot? Should Dunphy have allowed the status quo to remain until a new ballot? Did he go too far by instantly handing over control of the top position in the union to Short? All my doubts were resolved by the clear assessment and description in this book of the evidence – and Dunphy’s reasoning in his decision. Fraud, forgery, and falsity were proved. It was beyond reasonable doubt that Short would have won the election in 1949 but for the cheating that occurred.

A fascinating point revealed in the book is how late Short’s formal defection was from the Trotskyist camp. It was only in 1949, the same year that the Groups endorsed him as their candidate for Secretary of the FIA, that Short wrote to Nick Origlass to resign from the Labor Socialist Group (the then Trotskyist organisation). It is interesting to discover how many ex-Trotskyists had an influence on the mainstream of Labor politics in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Ted Tripp, a member of the Australasian Society of Engineers was one of the main speakers at the 1949 ACTU Congress proposing that the ACTU disaffiliate from the World Federation of Trade Unions and join the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. Tripp was the secretary of the Friends of the Soviet Union, a CPA front, in the 1930s before his move to the Trotskyists in 1937. Dinny Lovegrove rose to become secretary of the Victorian ALP in the early 1950s. He had been an active communist in the 1930s, broken with them and, after a brief flirtation with Trotskyism, become an implacable anti-Stalinist moderate within the ALP. In the Split he stayed with Official Labor. He subsequently was elected as a Labor member of the House of Representatives. Jack Henry, once very active in the Queensland Trotskyist movement, was a leader of the Group that won control of the Victorian Clerks Union in 1950. Jim McClelland, Short’s key legal adviser, and later a Labor Senator and Minister in the Whitlam government, was a Trotskyist in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The history and significance of the Trotskyists and the influence of their ex-supporters, sympathisers and those influenced by them is one story worth writing about, and this biography fills many important gaps, including the details of Short’s involvement.

Short was both a survivor and a victim of the Split. The man met and hailed by US President Eisenhower on his first visit to the USA in 1954 (who can imagine a labor union leader being ushered into an audience in the White House today?), the symbol of democratic and courageous Labor leadership in the contest against communists for control of Australian unions was, after 1956, pilloried as an extremist. Short was purged from the NSW ALP Central Executive in 1956. Suddenly everything was up for grabs; even survival within the union. What followed is largely the story of Short’s intelligence and personality, working to preserve the union and its leadership.

‘Discipline’, ‘determination’, ‘single-mindedness’, ‘passion’, ‘ideological beliefs’ — those terms have loaded meanings in political parlance. In sport and in business, ‘discipline’, ‘single-mindedness’, and even ‘passion’ are praise-words; in politics they can be swear-terms. Sometimes to describe a person as passionately single-minded in their political beliefs is to convey the flavour of a fanatic. This is often unfair. Someone who feels strongly about the right to change governments – of States as well as of unions, and who believes in earnest activity in defence of democratic values as well as against the challengers to democratic institutions may be ideologically driven. To describe such a person, on such grounds, as fanatical, is perverse. But as power shifted within the Labor movement in the mid-1950s, the discipline of Short’s supporters was characterised as somehow sinister.

One way that Short was able to ensure the longevity of his supporters’ control in the union was by building up an impressive industrial research and advocacy unit within the union. This was well regarded by the ACTU and metal unions generally. In the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the ACTU’s conduct of National Wage cases relied heavily on the FIA Research Department. However, from the mid-1970s, the quality of this Department atrophied.

After the Split many of Short’s ideas, whether about ‘responsibilities’ of union leaders,11 productivity negotiations, collective bargaining or, in the international arena, the desirability of forming an Asian bureau of free trade unions within which Australian unions would have a major role, were ignored or dismissed by many in the mainstream. (Ironically, in the 1990s less ideologically-charged times, union leaders seem to be endlessly talking about the merits of productivity bargaining, enterprise negotiations, co-operative industrial relations and the like. Internationally, the ACTU actively participates in the Asian Pacific Regional Organisation of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions and the South Pacific and Oceania Council of Trade Unions, which it helped to form in 1990.) In the late 1950s and 1960s many of Short’s ideas fell on deaf ears. “What would he know?”, “Grouper-loving bastard”, and other epithets greeted his contributions in various Labor forums. Prior to the advent of Whitlam as Labor leader and Hawke within the ACTU, much of what passed for Labor politics in the 1960s was both dreary and dopey. Nonetheless, amongst the wider public, Short’s statements were mostly popular and sounded sensible. He was a brilliant publicist – within the union movement, one of the best of all time.

Despite the loss in 1970 of the Port Kembla FIA Branch to a coalition of Left Labor and some communist party members, the empire did not collapse. Mary Dickenson in her study of the relations between the Port Kembla and other Branches of the FIA comments:

While many and various attempts were made to curtail the activities of the ‘Opposition’ leadership in the Port Kembla Branch, there was never any real danger of the destruction of this Opposition within the union nor any threats of secession or major split. The union’s political system accords sufficient legitimacy to opposition for political reversals to occur without destroying either the Opposition or the organisation. Nevertheless, the toleration of opposition places severe strains on the organisation at times.12

Perhaps the struggle between the Branches imposed a discipline on all sides to perform better and provide improved services to union members. The Port Kembla results forced the national leadership to pay greater attention to the needs of migrant members and to work harder to retain the support of members. Short, along with many of his colleagues, learnt some valuable lessons from the 1950s. Containing your opponents did not necessarily require their destruction. The next best thing to beating them at the ballot box was to encourage the ‘dissident’ or ‘opposition’ leadership in Port Kembla to contribute to the ideas and actions necessary for a better union and thereby support its unity and strength.

As someone familiar with Laurie Short’s life and times, I was surprised by how much I learnt in reading this biography. Susanna Short has the advantage of knowing her father very closely. But that’s not the reason for the success of this biography. Even if much of the book is sympathetically written, there are plenty of critical reminders that sometimes heroic individuals are flawed and fallible and commit mistakes. Perhaps the best compliment Susanna could pay to her father is that this work does not sink into a bog of sentimental mush. There are some points of emphasis and interpretations that I do not agree with and which are bound to be controversial. For example, I can’t agree with the assessments made about Short’s connection – and that of some of his supporters and the organisations with which he was associated – with intelligence agencies, as the book’s treatment seems too generous about the credibility of some of the conspiracy theories. But the great accomplishment of this book is its ability to convey facts and argument and to leave it up to the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Notes

1) Norm Gallagher was the hardline communist, folksy beer guzzler and ruler of the Builders’ Labourers’ Federation. He helped to build up the prestige, respect and wage entitlements of the unskilled workers who were his members. But he was ruthless with opponents and sometimes thuggish. His union was deregistered federally, in NSW and in Victoria in 1986 on grounds of corruption.

2) Lipset, Seymour Martin, Trow, Martin A, and Coleman, James S., Union Democracy: The Internal Politics of the International Typographical Union,Free Press, Glencoe, 1956, p. 401. This book is a classic study of the problems of democracy and participation within a union.

3) Santamaria, B.A., ‘The Movement of Ideas in Australia’, Voice, The Australian Independent Monthly,Vol. 4, No. 1, October-November 1954, p. 17. This issue of Voicereprints most, but not all, of Santamana’s speech. The transcript of the speech, delivered in 1953, can be found in the Lloyd Ross Collection, NLA MS3939. The transcript is not dated and there is some dispute as to whether speech was delivered in 1953 or later, in 1954. Robert Murray argues for the later date in The Split: Australian Labor in the Fifties, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1970, p. 177.

4) Ross, Lloyd, ‘Anti-Red Issue in Anti-Red Fight’, Herald (Melbourne) 26 February 1953.

5) Ibid.

6) These descriptions are to be found in Hagan, Jim and Turner, Ken, A History of the Labor Party in New South Wales 1891-1991, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1991, pp. 163-4.

7) Wran, Neville, ‘Foreword’ to Evatt, H.V. William Holman. Australian Labor Leader, Angusand Robertson (abridged edn), Sydney, 1979, p. vi.

8) See Kane, J.T., Exploding The Myths, The Political Memoirs of Jack Kane, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1989, pp. 118, 135. See also Dickenson, Mary, Democracy in Trade Unions, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1982, pp. 56-7.

9) Ross, Lloyd, ‘Some Movements of the Rank and File’, Twentieth Century, Australian Quarterly Review, VoL V, No. 1, September 1950, p. 36.

10) Ibid., p. 37.

11) See, for example, Rawson, Don, ‘Politics and “Responsibility” in Australian Trade Unions’, Australian Joumal of Politics and History, Vol. IV, No. 2, November 1958, pp. 224-43. This article, inter alia, discusses some of Short’s ideas.

12) Dickenson, Mary, op. cit., p. 111. See also Dickenson, Mary, ‘Biography of a Trade Union Leader’, Australia 1939-1988, A Bicentennial History Bulletin No. 1, May 1980, pp. 38-45.

Postscript (2015)

Curiosity first led me to Laurie Short’s door.

I enrolled in 1977 in a MA (Hons.) at the University of NSW, my supervisor, Professor Doug McCallum, agreed to the general theme, on the political and social philosophy of Professor John Anderson, Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney, who had an influential place in Sydney intellectual life from his arrival from Scotland in 1927 to his death in 1962. Part of Anderson’s journey encompassed a period as a supporter of the Trotskyist movement in Sydney in the 1930s, as he was losing his illusions about Stalinism.

My interest in understanding that milieu of anti-Soviet leftism led me to developing an interest in Short (1915-2009), who joined the movement as a teenager. I knew from Jim Davidson’s appendix to his The History of the Communist Party of Australia (1969) a bit of the early history of Trotskyism in Australia. I learnt from Short that he got involved aged around 16 in 1931 or thereabouts.

Broadly, I knew already of Short’s successful battles in the late 1940s/early 1950s, against brazen vote rigging by the then communist leadership, in the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA), once Australia’s largest union.

By the time I met him, in 1977, he was still recovering from a stroke. Barrie Unsworth told me Laurie had slowed down.

He was wiry, humble, curious, alert, a man of apparent vast interests, reading and opinions, Short by name and just 163cm tall.

We learnt to chat about all matters, though mainly on aspects of politics. He was immensely proud of Nancy Borlase, his abstract artist wife, companion and guide to the cultural world. He retained a healthy scepticism of the pretensions of the vain and the attractively charlatan.

He was not a great fan of Whitlam.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, as counsel, Kerr had defended Short in the FIA court battles. Short was loyal to a fault. He greatly admired Senator Jim McClelland, fellow ex-Trot, who had been a solicitor assisting the Short forces in the early days of battles in the union. But post the Whitlam government sacking in 1975 by the Governor-General Sir John Kerr, he thought Diamond Jim’s fierce criticisms of Kerr vindictive and unfair.

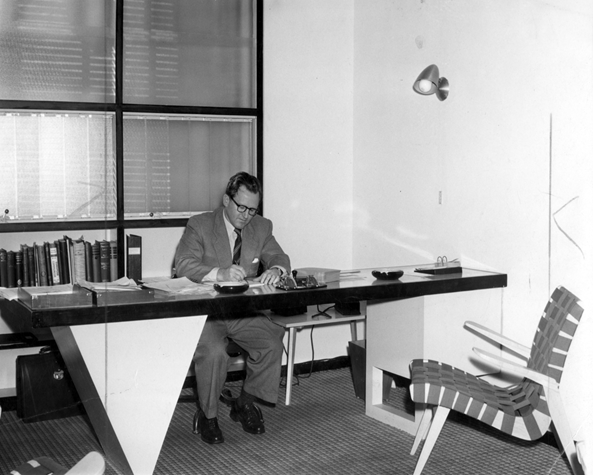

The national offices of the union were then close to Circular Quay at 188 George Street, Sydney, in an old brick building, I assume a former warehouse, now demolished. A man sitting on a stool would operate the elevator. He would press the button to go to the nominated floor. A veteran of war or an injured comrade was being looked after with employment.

In early 1978 Short invited me to apply for a research officer’s position in the union. But at the same time, I had been asked by Barrie Unsworth and Bob Carr to apply for the Education and Publicity Officer’s role at the Labor Council of NSW. I urged my friend Steve Harker to go for the FIA role and he did a great job there.

In one of our discussions, Short paraphrased Max Eastman, the American intellectual, ex-Marxist and ‘recovered Trot’: “following the Trotskyist movement is a bit like watching an onion committing suicide – there are so many splits occurring”; he attributed his phrasing of “opposition to the bloodstained iron-heel of Soviet despotism” as derived from something Eastman wrote.

When in 1981 I studied at Harvard at the Trade Union Program at the Business School, I caught up once with Professor Dame Leonie Kramer (1924-2016). She was then a visiting professor; we knew each other slightly on the board of the NSW ABC Advisory Committee, which she chaired. Short told me to ask how she was faring over there. He too, somehow, had got to know her. Dame Leonie told me that Laurie had been sending her weekly clippings of the news from Australia. At one of his retirement celebrations in 1982, one of Kramer’s children, Hillary, sat next to me at the function and she spoke warmly of her mother’s admiration for Laurie.

There were some similarities with John Ducker that I noticed. (Ducker was formerly an Organiser with the FIA). Both were bower-bird readers, squirrelling away pieces they liked for further examination, copying material for friends, reading widely, particularly interested in articles in the UK and US on small-p progressive politics, the labour movement, and especially, communism. The latter we saw as our mortal enemy. Occasionally, in the Labor Council office, I would get a memo from Ducker: “you might be interested in this”; with compliments, etc., with an article to read. It made it easier to converse with those legends. They were interested in what I thought and they were interested in feedback, and any suggestions of my own on what to read.

Ducker was more interested in Catholic social justice and writings from the moderate UK Labour types and their journal Socialist Commentary. Some of what ‘bruvver Ducker’ sent me was old. As well as contemporary material, he wanted to delve into what he had collected to send on. My education and immersion into a worldview was being discovered and shaped.

Short read more widely with eclectic interests, and there were a lot of American journal clippings in what he sent — from the New York Review of Books, The Nation (rarely), The New Republic, Commentary, — as well as the UK New Statesman.

We were political soulmates. I am not sure how many other Labor people of my vintage knew about Max Eastman, James Burnham, Max Shachtman and others Short had read in his younger days. In the late 1970s Laurie thought I might be interested to meet an old friend, Ken Gee QC (1915-2008), another ex-Trot, who over a dinner insisted I read Eugene Genovese’s Marxist-influenced writings on the political economy of slavery in the United States. Roll, Jordan Roll: The World the Slaves Made (1974) being one outstanding piece of Genovese writing. Gee, by now a champion of Taiwan and earlier, South Vietnam, came to certain positions through his anti-Stalinist lens. He later wrote a book, Kenneth Gee, Comrade Roberts. Recollections of a Trotskyite (2006).

Prime Minister Bob Hawke, when speaking in Sydney at the launch of the Short biography, referred to the old FIA’s research department as the envy of the movement, and praised the union’s effectiveness in dealing with a really tough set of employers, particularly BHP, and he praised the role played in the annual wage claims, both in the metal industry and in basic wage adjustment cases, heard by the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission.

Hawke compared Short’s path through the labour movement as akin to the loneliness of the long distance runner, pacing towards his destination, buffeted by unexpected storms, almost blown off course, but still determined to run on, no matter the odds.

Hawke thanked Short for staying with Labor during the tumultuous mid-1950s, helping to save the party in NSW from its most destructive elements, and thereby laying the foundation, ultimately, for Labor’s renewal. But Hawke saw too the emotional and intellectual turmoil that all of that must have meant.

During the ALP Split, Short’s deputy and national assistant secretary of the FIA, Harry Hurrell (1923-1988), wanted to go with what became the DLP. He was particularly incensed with the treatment of Jack Kane (1908-1988), the NSW ALP Assistant General Secretary, who was campaign director for Premier Joe Cahill’s successful re-election as Premier of NSW in 1956, and who was sacked soon thereafter through Federal ALP takeover of the NSW branch of the ALP. Kane later became a DLP Senator from NSW, 1970-1974. But in the case of Short and Hurrell, one a secular ex-Trot Laborite and the other a Catholic Labor man, sharing a common enmity to communism and far leftism, and with many overlapping views, including revulsion at Kane’s and NSW ALP Country Organiser Frank Rooney’s dismissal and, soon thereafter, expulsion from the party, the old allies were not going to bust up now. The NSW Branch could go one way (with Labor and “stay and fight”) with the Victorians leaving the party.

For Short, it must have been dreadful period, as he was ostracised and accused of being too hard-line by some former allies. I understood his journey, the choices and conflicts, the traps and pitfalls along the way.

He retired in 1982 (replaced by Hurrell) but popped into the FIA office most days to chat, read, and escape the boredom of retirement. Eventually, he slowed down, visiting the national office more rarely.

In September 2004, I picked Laurie up from outside his flat in Mosman, drove to an Italian restaurant he had recommended over the phone the day before. He slowly, awkwardly, got out of the car, walking stick in hand, shuffled to the door and a seat at the table. And then he sprang to life. Over pasta he quizzed me on Latham. It was after the handshake with Howard. I got the impression he did not favour a change of prime minister at this election.

He worried about the aftermath of Steve Harrison (1953-2014), Harry Hurrell’s choice to lead the union, who was FIA Secretary from 1988 and then through a series of amalgamations, including with the Ausrtralian Workers Union (AWU) in 1993, to messy resignation in 1997, whether much, if anything, of the old FIA would survive. At this point, Bill Shorten was national secretary of the AWU. Laurie had time for Paul Howes, a former Trot, who had worked at the Labor Council and was now the AWU heir apparent as national secretary.

In 1994, when leaving the Labor Council, selection for the Senate denied, he rang me several times before and after we knew how things would go. Laurie said that for him it was a sad day that his union had contributed to the fall. He hoped I might stay interested and return to the fray. But he understood if I wanted no part of that anymore.

We understood each other.

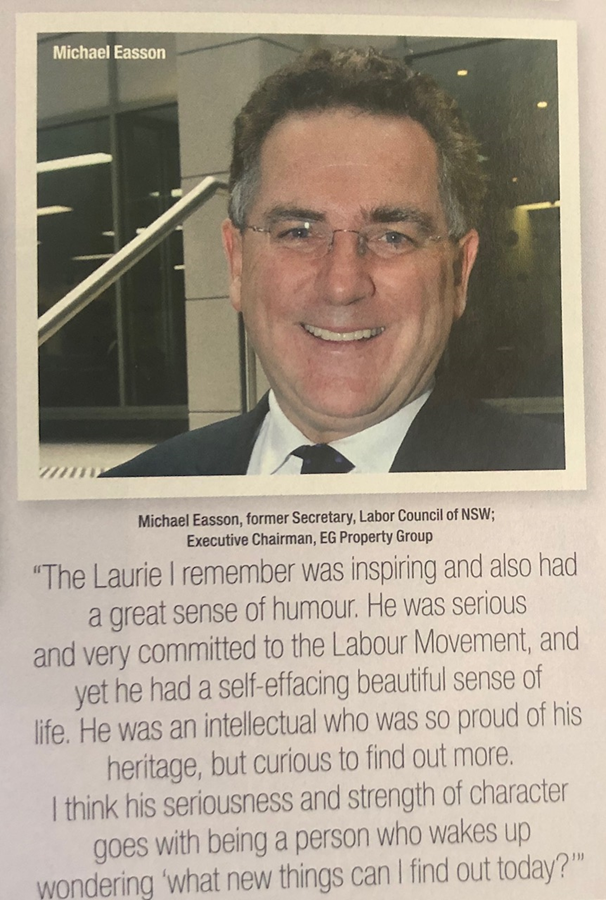

On Laurie’s death in 2009, at a commemoration at the Sydney Trades Hall, I commented of Short: “The Laurie I remember was inspiring and also had a great sense of humour. He was serious and very committed to the labour movement, and yet he had a self-effacing beautiful sense of life. He was an intellectual who was so proud of his heritage, but curious to find out more. I think his seriousness and strength of character goes with being a person who wakes up wondering ‘what new things can I find out today?’” – cited in The Worker, publication of the Australian Workers Union, Issue 2, 2009, p. 15.

One major error in what I wrote in my Foreword concerns Denis “Dinny” Lovegrove (1904-1979), who was a State not a Federal MP, winning Carlton (1955-1958), Fitzroy (1958-1967), Sunshine (1967-1973) in the Victorian Parliament. It was a stupid error about someone whose political history I generally knew. The then Senator Robert Ray rang me to highlight the error.

In late 1977, from Sydney, explaining that I would be in Melbourne the next week, I phoned Lovegrove to ask if I could interview him about his political history, particularly his move from Trotskyism to mainstream Labor as well as about his writing and activities as “comrade Jackson”, his nom de plume started in his earlier communist days. He responded: “I don’t talk about that. It was so long ago”, and hung up the phone. In winning the state electorate of Carlton, Lovegrove defeated John Barry, a veteran Labor MP since 1932, Minister for Health in the Cain Victorian Labor government, expelled from the ALP in March 1955 (during the Split), who then led the Australian Labor Party (anti-Communist), a precursor to the Democratic Labor Party.