Article written 31 October 1995, submitted to the Australian Financial Review, but never published.

The defeat of Tom Donahue as President of the AFL-CIO last week by John Joseph Sweeney is a tragedy. Far from heralding a new era for aggressive and innovative unionism under the new leadership, Mr Donahue’s defeat may be another milestone marking the slow decline of American organised labour.

The former AFL-CIO President, Mr Lane Kirkland, who resigned in embarrassing circumstances a few months ago, has a lot to answer for.

To understand the recent election, it is necessary to recount some of the happenings that occurred this year.

Donahue who, as the secretary of the AFL-CIO was Kirkland’s heir apparent, decided in April this year to call it quits. He privately asked Kirkland what his intentions were, and the incumbent said he wished to serve one more term as President of the AFL-CIO. Though he is aged 67, Donahue is very dynamic and has developed many of the most progressive activities of the AFL-CIO. For example, the financial services arm of the AFL-CIO – something which influenced the Australian and the UK labour movements – was pioneered by Donahue. He also set up the Organising Institute, despite Kirkland’s reservations. Donahue played a major role in attempting to get American labor to play a more influential role on trade issues in the United States.

Kirkland who is 73 and started life in the AFL-CIO as a speechwriter for George Meany wanted to stay on as President to 75. He saw no reason to resign and wanted to enjoy the added prestige of being head of the American labor movement at a time of a Democratic presidency.

However, there were many American union officials critical of Kirkland’s approach to contemporary issues and his recent ponderous speaking style. He sounded like a man slowing down. Kirkland can claim a good deal of credit for the American labor movement’s effort in supporting Solidarity and other eastern European labor unions during the 1970s and 1980s. Millions were raised by Kirkland to support those organisations, and, in this sense, Kirkland might be regarded as the George Soros of the emerging democratic labour movement in that part of the world. But like Mr Soros, a lot of money was spent with mixed results and with little success in some countries.

Kirkland, a dedicated anti-communist, was in the George Meany mould. Which means that in the post-cold-war period, his approach to the major issues of the day could appear dated.

Donahue, however, was no ideological simpleton. He saw the world in pragmatic terms though he was influenced by the Social Democrats USA (a small, moderate ideological element in the American Democratic Party with origins in the old, now defunct Socialist Party). Accordingly, he took an interest in international matters and the staffing of the international affairs department of the AFL-CIO.

When Kirkland decided that he would re-nominate for election in October, this set the union movement alight with intrigue. Mr Sweeney along with some of the major unions was concerned that American unions had lost influence in Washington. Also, the alleged, cosy approach to dealing with American big business struck Sweeney as anachronistic. What had business done to help Labor in the last few decades?

Accordingly, earlier this year Sweeney decided to approach Donahue to say that his union, the Services International Employees Union (SIEU), one of America’s biggest, along with the International Association of Machinists, and the United Food and Commercial Workers Union would support him for President. But when Donahue publicly announced his decision not to re-contest the position of secretary and to retire in October (rather than challenge outright his esteemed colleague Mr Kirkland for the presidency), instead of quickly provoking Kirkland to re-assess his position, it galvanised Kirkland’s opponents to resolve to oppose him.

Sweeney threw his hat in the ring and came up with a “dream ticket” including as Secretary-Treasurer Mr Richard Trumka of the mine workers who had been elected three years before and had done much to revitalise the credibility of that organisation. Sweeney also, as the campaign went ahead, decided to promote an American Latino female leader Mrs Chavez Thompson, presenting himself as a person more interested in industrial than international affairs and more concerned about assisting workers in gaining jobs and better labor practices in America, rather than fighting foreign battles. That was his pitch. Sweeney claimed to be a person in tune with the key support bases of the American labor unions, especially blacks and Hispanics.

Kirkland realised as pledges of support came in for Sweeney (which gave the challenger a minimum of 60% of the vote at any AFL-CIO congress) that the game was up. Accordingly, he decided after a bruising 5 months of public criticism to ask Donahue to reconsider his decision to retire later in the year and instead to take up the position of President of the AFL-CIO immediately. Accordingly, Kirkland resigned in August and Donahue was elected by the executive of the AFL-CIO to take his place.

It was short term, however, as Mr Sweeney managed to beat his rival in last week’s contest. Ironically it was Donahue who recruited Sweeney into the union movement. Donahue hired Sweeney as a business agent (the equivalent of a union organiser in Australia) in New York for the SIEU. Old friends fell out and Sweeney refused to allow Donahue his cherished one term as president – especially as Sweeney pointed out that the offer was there earlier in the year. Mr Sweeney had declared his intentions and settled his succession in his union in a way that meant that a return to the presidency of his organisation was near impossible.

The tragedy for Donahue is that he will never have the chance to implement some of the major ideas that he harboured but felt was never able to openly promote within the American union movement. For example, it was Donahue who sponsored academics and union activists to write a report on The Future of Work that was published at the 1985 AFL-CIO congress (and which had an influence on the ACTU in their thinking at the 1987 ACTU congress including the support for industry unionism and greater support for a “services approach” to unionism). Donahue believed that one of the things the American union movement had to do was to support associate unionism and to be much more innovative in the way that the union movement pitched itself to non-members – especially in the south, and in the technology and computer services industries.

A problem for the Sweeney camp is that many of his supporters are haters of bosses. About 7 years ago the class-consciousness of much of the American labor movement came “home” to me when a delegation of American labor leaders spoke at a Labor Council of NSW meeting in Sydney. The stories about vicious anti-union attacks by employers in America was something that shocked most people at the meeting. Australia’s long period of co-operative, even clubby, industrial relations is a long way from the US idiom. What was also surprising was the venom felt for employers by the US union leaders. It seems that the United States is one of the last bastions of class-consciousness in the developed world.

A combative, hostile approach to American business may not be the best way to pitch the union movement’s appeal.

Mr Sweeney can claim that his “Justice for Janitors” campaign is an example of what needs to be done. A few years ago, his union promoted a wage campaign for janitors which led to stormy demonstrations outside of employers’ offices and a very noteworthy media campaign. Wage rates were significantly increased as a result of this stance and Mr Sweeney thinks that such an approach can pay dividends in other sectors of the American labour movement.

Ironically for Mr Donahue, it may be a former protege who now has the chance to revitalise the American Labor movement. It is a tragedy for Mr Kirkland that all the good things he achieved, especially in the international arena, is overshadowed by his departure. Like Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential elections, the dark shadow of the President he served so long eclipsed Mr Donahue’s chances of victory.

Postscript (2015)

I was unable to convince any of the newspaper editors to publish this.

I knew that the change of leadership at the AFL-CIO was a major event and would have a significant impact on American Labor and ultimately the Democratic Party.

It would likely end the influence of the tiny Social Democrats USA grouplet, which for several decades had been influential in shaping the AFL-CIO’s stance on many foreign policy issues.

Richard Trumka, the head of the United Mine Workers of America I saw as ideologically ill-disposed to the AFL-CIO’s tradition of anti-communist, social democratic toughness. He had a long association with left-wing ratbags. Trumka would go on to serve as Secretary-Treasurer of the AFL-CIO, from 1995-2009, and then President (to date), replacing Sweeney when he retired aged 75, older than Lane Kirkland (1922-1999) was when he left as AFL-CIO President.

Al Shanker (1928-1997), the AFL-CIO ranking senior Vice President of the AFL-CIO and the head of the American Federation of Teachers’ union refused to shake hands with Sweeney when he won election at the AFL-CIO convention in October 1995. Shanker thought that Sweeney, an erstwhile ally, and colleague of Donahue, was turning his back old friends and traditional alliances and was in dalliance with the far Left.

Sure enough, all the people I knew were purged.

A less business friendly, and frankly less sophisticated AFL-CIO leadership, were now steering the ship.

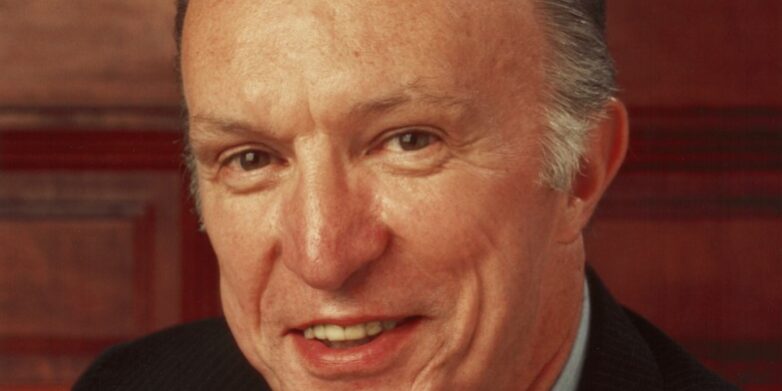

This was a tragedy for Donahue (1928- ), whom I got to know very well. When I would visit Washington, I would see him. When he was in Australia in 1988 for the International Confederation of Trade Unions conference (in Melbourne) he popped up to Sydney. Tom and his wife Rachelle Horowitz (a Vice President of the Democratic Party and one of the organisers, with Bayard Rustin, of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” 1963 March on Washington), and Mary, my wife, and I saw Sarah Vaughan, the “Divine One”, the world’s greatest female jazz singer, then at the peak of her talent, perform in March 1988 at the Sydney Opera House.

Once in Washington, in 1992 or early 1993, I spoke to Donahue about the Australian approach to restructuring, what Keating called the “helping hand” to assist workers retrain, and re-skill following employment changes due to the restructuring of the economy. I suggested that this might be the approach to adopt with the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and President Clinton. And get government and business funding. Instead, the AFL-CIO campaigned against the Treaty, delayed its ratification, until in November 1993 Canada, the United States and Mexico ratified NAFTA after the addition of two side agreements, the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC) and the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC). The former, as its title suggested, provided for formal and informal cooperative consultations on labor issues. It was nothing like what we chatted about. With Sweeney and Trumpka suddenly in charge, they were more interested in repudiation than making NAFTA work better for displaced employees.

In retrospect the election of Sweeney and Trumka was the beginning of an isolationist, America-first approach by the union leadership. Additionally, in the unions, the drift to more leftist stances ironically isolated members and potential members from the leadership, putatively elected to replace the so-called old moribund leadership and more effectively appeal to a wider constituency, as their rhetoric put matters.

Many workers were social conservatives who saw many traditional labor union leaders as socially conservative too, thereby not feeling out of place. Under new leadership, the AFL-CIO was less of a grand coalition and no check on the Democrats’ rapid move to political correctness on social issues, as they embraced identity politics. Many rank-and-file union members felt alienated from what traditionally was their party. Although economic interests, particularly trade, kept many loyal to the movement, cultural tensions were rising.

In 1960 Donahue had been persuasive in getting Sweeney to leave the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) to become a contract director with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), Local 32BJ, a branch of SEIU headquartered in New York City. From there Sweeney was to rise to SEIU President. Donahue thought he could rely on Sweeney to give him time to coax Kirkland out of the Presidency and thereby leave with dignity. But this was not to be. Once Donahue gave notice to resign after 16 years as AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer, the writing was on the wall. Although Donahue was elected by the AFL-CIO Executive Board as President in August 1995, as a panicked Kirkland saw that he would be voted out of office, Donahue was then defeated by Sweeney in a full vote of the AFL-CIO delegates later in the year.

I found Donahue dynamic, thoughtful, articulate, and innovative. He was better than Sweeney, he was Sweeney plus, loyal to old colleagues and certain traditions. As Secretary he did so much in organising drives and creatively thinking about new services and using technology to reach to new and existing members. I also met Sweeney a few times. I thought he was a good organiser, an effective speaker, but lacked Donahue’s strategic depth, nous, knowledge, and tactical acumen.

Under the new leadership, the previous AFL-CIO officers were soon pilloried as lazy sycophants of government and big business.

Even former close allies of Donahue and Kirkland began to dance to the new tune. History was re-written. Even Jay Mazur, the “international” President of ILGWU, whom I met in the early 1980s when he was a member of the Labor Committee for Pacific Affairs, changed steps to waltz with the new band. International activities were scaled back, on the pretence that the new AFL-CIO wanted to be more focused at home. This enabled more former loyalists of the old regime to be weeded out.

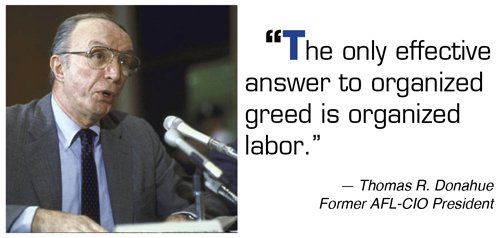

In retirement, in a spirited defence of AFL-CIO foreign activities, Donahue disputed the caricature that they were State Department lackeys. His 2000 letter to the editors of Foreign Affairs journal is worth reprinting:

To the Editor:

Too little attention has been paid to the dark consequences of free trade, and too many misunderstandings of organized labor’s positions on trade matters have been spread. So the recent article by Jay Mazur, president of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees, was welcomed. It is regrettable, however, that Mazur did not define the “new internationalism” beyond suggesting that it is based on “new alliances” with “environmentalists, human rights groups, and religious and consumer activists.”

The American labor movement has always been involved with the well-being of workers in other lands. Its first resolution on foreign policy, adopted in 1882, condemned England’s unjust treatment of Ireland and expressed solidarity with Irish farm laborers. It was Samuel Gompers, the American Federation of Labor’s first president, who convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the need to create the International Labor Organization within the League of Nations – the league’s only surviving component today. From 1932 on, American labor sparked the campaign to alert the world to the dangers of Hitler’s totalitarianism and to save the leaders of the unions that he dissolved within days of taking power – a campaign led by the former president of Jay Mazur’s union, David Dubinsky.

After World War II, organized labor helped rebuild democratic trade unions in Europe. It identified itself with the nascent trade unions of North Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere in their struggles to end colonialism, as well as with the efforts of displaced Jews to create a homeland in Israel. Later, American labor fought apartheid, supported the formation of black trade unions, and was among the first American organizations to support sanctions against Rhodesia in the 1970s and later against South Africa. In more than 50 countries, the AFL-CIO helped workers develop independent unions to protect and advance their interests, both on the job and in civil society. It was a relentless foe of all forms of totalitarianism. It had and still has only one test by which to judge a nation: Is a free and democratic union movement allowed to function there?

Against this background, Mazur writes that in the post-World War II years the international role of the labor movement was “more geopolitical than industrial” and was defined “mainly through the prism of anticommunism.” Although this artful writing is not intended to demean the efforts of American unions to help workers everywhere have free and independent unions, it does so nonetheless. Mazur’s article supports those who denigrate labor’s international defense of free, democratic unions and those who now suggest that anticommunist activity was somehow less than honorable.

It suggests that these were cynical struggles for geopolitical power in which labor was a pawn of the government, rather than efforts to ensure that workers could defend their interests. When David Dubinsky and his colleagues fought for free unions, they were no one’s pawns. When American labor’s Michael Hammer and Mark Perlman, and Rodolfo Viera, president of the Salvadoran Peasant Workers’ Union, were gunned down in San Salvador as they tried to advance the land distribution program, their struggle was between rich landowners and workers. Many more examples illustrate that American labor’s engagement with other unionists has been premised on the determination to ensure, as the late AFL-CIO President Lane Kirkland put it, that “ordinary people don’t get kicked around by the rich and powerful.”

Mazur’s article suggests that today’s unions are engaged in the new internationalism as a matter of self-protection and that “following the work” as it moves to other countries is necessary to protect American workers. To some extent this is true, but the labor movement was helping workers abroad for reasons of solidarity and humanitarianism long before the movement of work became significant. The labor movement has argued for the inclusion of workers’ rights in every international trade negotiation since the Tokyo Round of the 1970s. Current efforts to ensure respect for core labor standards around the world come from the same inspiration.

Mazur properly highlights the need for U.S.-based corporations to take a hard look at not only their behavior abroad (in terms of wages, conditions, workers’ rights, and environmental issues) but at the places they invest their money. A study released last November by the New Economy Information Service found that the developing democracies’ share of total developing-country exports to the United States (excluding oil) fell from 53.4 percent in 1989 to 34.9 percent in 1998. In terms of manufactured goods exported to the United States – vital to a developing country’s economic success – developing democracies’ share fell by 21.6 percent, to 35.1 percent. U.S. direct investment in manufacturing in developing democracies remained largely stagnant while nondemocratic countries (mainly China) gained 5.7 percentage points.

If American corporations are as serious about their commitment to democracy as American unions are, they must be willing to work with developing democracies toward economic development that truly improves working conditions through respect for workers’ rights and decent wages. These corporations can help ensure the development of democracy throughout the world and, at the same time, make consumers out of decently paid workers.

Thomas R. Donahue

Former President, AFL-CIO

Foreign Affairs, Vol. 79, No.3, May/June 2000

Like most Australians, including many in the labour movement, I am more of a free trader (but with a Labor heart) than Donahue would ever be, and so we would disagree on some macro matters.

On the need for unions at home and abroad to defend democratic and labour rights, we were and are as one.