Published in Michael Crosby and Michael Easson, editors, What Should Unions Do?, Pluto Press and the Lloyd Ross Forum, Leichhardt, 1992, pp. 97– 149.

…the Japanese have certain old traditional virtues which can help to keep them on an even keel. One of these is that self-responsibility which they phrase as their accountability for ‘the rust of my body’ – that figure of speech which identifies one’s body with a sword. As the wearer of a sword is responsible for its shining brilliancy, so each man must accept responsibility for the outcome of his acts. He must acknowledge and accept all natural consequences of his weakness, his lack of persistence, his ineffectualness. Self-responsibility is far more drastically interpreted in Japan than in free America. In this Japanese sense the sword becomes, not a symbol of aggression, but a simile of ideal and self-responsible man. No balance wheel can be better than this virtue in a dispensation which honours individual freedom, and Japanese child-rearing and philosophy of conduct have inculcated it as a part of the Japanese Spirit.

Ruth Benedict: The Chrysanthemum and the Sword

When the subject of ‘what should unions do?’ comes up at union gatherings in Australia it is rare that the Japanese experience is seriously discussed. When the topic of Japanese labor unions is raised it is frequently in pejorative tones. When you ask the average Australian trade union activist what s/he imagines about Japanese labour, s/he will normally respond by reference to ‘the company unions’. Such unions are generally regarded as weak and lacking in resources and independence from company management. Moreover, there is a view that the form of Japanese labour relations has mysteriously emerged out of the mists of Japanese culture and history. Japanese are sometimes said to be different. Their sense of self-responsibility and, in Ruth Benedict’s arresting phrase,1 their accountability for ‘the rust of my body’ suggests attitudes to work which are foreign to the outlook of, for example, Australian workers. Whether such culturalist interpretations are true, or not, is an interesting question. But such views are widely believed both within Japan and abroad. So, the idea that an understanding of the development and experiences of Japanese unions may be of potential value to the Australian labour movement seems as remote as the crossing of the wattle with the chrysanthemum.2

The purpose of this chapter is to briefly outline the recent development by the ACTU of an approach to restructuring the Australian trade union movement, to compare that approach with Japanese industrial relations and to outline some things that the Australian labour movement might discover and adapt to, based on Japanese experiences.

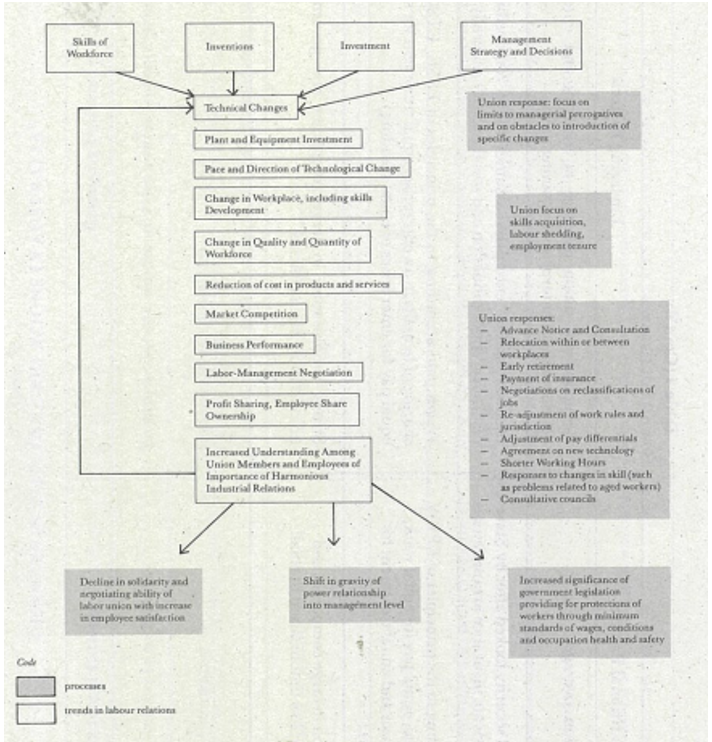

The major theme of this chapter is that the Japanese have invented an industrial relations culture which is relevant to that which Australian unions and the labour movement might pursue in the 1990s. But in describing the situation in Japan it is necessary to emphasise four points relevant to the dynamics of labour relations.

One of the most tempting of explanatory options is the argument that: ‘what is had to be’. It is a natural and an almost compelling idea to assume that a social situation, institution or movement is the logical outcome of historical, cultural, economic and other forces – including the actions of individuals. Obviously, events happen and they have their causes. Usually, however, social and economic situations do not mechanically and inevitably ‘emerge’ – they are the results of the struggle between competing forces. Thus, the history of Japanese industrial relations is largely the story of various tendencies, movements and forces which interacted, modified and became what might be described today.

A second error would be to insist that there is any final form of societal structure or way of doing things. In economics and social life there is always change – sometimes evolutionary and sometimes an inventing of the new. Joseph Schumpeter’s notion of ‘creative destruction’ provides a useful analogy. Schumpeter suggested that capitalism can never be stationary and that the ‘impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organisation that capitalist enterprise creates’. Schumpeter argues that economic structure is changed from within – ‘incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one’.3 Japanese industrial development – and the contribution made by workers to those changes – is particularly fascinating in illustrating the processes of change. The various transformations in labour relations over the last forty years in Japan including the style, outlook and actions of unions, illustrates that there is almost nothing that is permanent and unchanging.

A third mistake would be to regard the industrial relations system of an economically advanced and liberal democratic society as a matter of describing something universal across that society. In a police state it may be possible to describe its industrial relations system in such a neat, clear and dogmatic fashion. There are various systems and peculiarities within a democratic society – in marked contrast to ‘summaries’ which assert that so-called defining characteristics of industrial relations patterns are the only characteristics worth mentioning. It might be noted that when someone talks about the ultimate characteristics of something, in an effort to maintain there is a single direction or pattern or purpose towards which everything works, this is usually in contradiction to how things actually work – where there are various directions, patterns and characteristics. In this sense it is hard to describe the industrial relations system of any country. It might be assumed that patterns vary across industries – to cite just one example, between (say) the government business enterprises and the small, private sector firms. The Japanese industrial relations system is complicated. That this is not apparent in the stereotypical images presented about Japan should not be surprising. Simplistic presentations of reality are usually uncertain guides to the incredibly complicated and different ways that things happen. This is no mean, pedantic point. What is worth bearing in mind in discussions about Japanese labour relations, for example, is that the theoretical and descriptive literature should always be judged against empirical reality. Incidentally, it might be noted that labels like ‘Asian’, ‘Japanese’ and ‘Western’ – as in the term ‘Japanese labour relations’ – are illuminating in fewer and fewer contexts. It is more illuminating to examine what is involved in labour relations in particular industries and in particular enterprises.

Also worth stating is this fact: descriptions of industrial relations which pay scant attention to wide economic questions, including the types of industries, circumstances surrounding the labour market(s), work organisations, skills development and so forth are merely revealing a glimpse of the total picture. Similarly, any account of Japanese trade unions which tells the story of structures, functions and styles of unions without detailing the impact of the wider economic issues runs the risk of explaining very little. It would be like describing the plot of Hamlet without mentioning the Prince of Denmark; perhaps something interesting of that kind might be attempted – but it would be something different to an accurate account of Shakespeare’s play.4

Before exploring really existing Japanese industrial relations, this Chapter will touch on current priorities of the Australian union movement to modify its structures and outlook as to what unions might usefully do.

The ACTU Approach

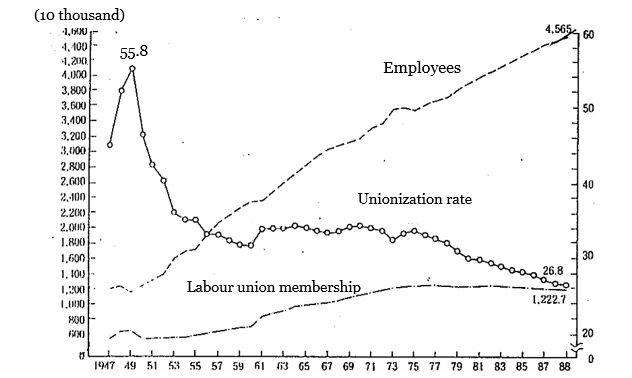

The three key documents which set out the ACTU’s strategy to reorganise the union movement are: Australia Reconstructed,5 the report of the joint ACTU/Trade Development Council ‘mission to Europe’ in 1986. The Future Strategies for the Union Movement,6 a policy paper discussed and endorsed at the 1987 ACTU Congress; the style and content of that paper was heavily influenced by the Australia Reconstructed document and the reports by the AFL-CIO on the Organisation of Work.7 The third document is the policy adopted by the 1989 ACTU Congress on the Organisation and Services of the Trade Union Movement.8 In none of those papers are there any references to Japanese unions or labour relations in Japan. In part, this reflects the preoccupation with Australian circumstances and a lack of interest in the Japanese story. In addition the normative policy orientation of the latter documents limited comparison with overseas union experiences.9 Perhaps the declining unionisation rate in Japan – falling towards a quarter of the workforce, as diagram 1 illustrates – meant that Australian unionists were more interested in countries like Sweden where unionisation rates exceed a majority of the workforce.10

Diagram 1: Changes in Number of Employees, Labor Union Membership and Estimated Unionisation Rate in Japan: 1947-1988

Source: Japan Ministry of Labour, Basic Survey on Trade Unions; Nikkeiren11

In Australia Reconstructed something called strategic unionism was endorsed; the report observes:

Trade unions in most countries concern themselves solely with the issues of wages and conditions, job security, a higher general standard of living and social justice but it is a distinctive feature of Austria and the two Scandinavian countries visited by the Mission (i.e., Sweden and Norway) that they have broadened their vision and embraced Strategic Unionism.

Strategic Unionism has the following characteristics:

-

- a tendency for trade unions to go beyond a narrow focus on wages and conditions;

- the generation and implementation of centrally co-ordinated goals and integrated strategies; e.g., for full employment, labour market programs, trade and industry policy, productivity, industrial democracy, social welfare, and taxation policies which promote equity and social cohesion;

- sophisticated participation in tripartite bodies;

- a commitment to growth and wealth creation as well as its equitable distribution;

- the active pursuit of these goals and strategies in their own right, both inside and outside of the arena of industrial relations; with

- the emphasis upon strong local and workplace organisation, and

- the extensive delivery of education and research services.

There is evidence to suggest that Strategic Unionism is a major variable in explaining divergences in economic performance and social equity in OECD countries. (Emphasis in the original.)12

Several observations might be made about the Australia Reconstructed Report and its advocacy of the theory of strategic unionism. First, the authors regard strategic unionism as something more substantial than mere economism – the preoccupation with only wages and salary issues. (Economism is a term usually associated with Lenin’s castigation of the limited and servile activities of non-revolutionary union organisations.13 For Lenin, of course, the political orientation of unions and their role as vehicles for the radical transformation of society are critical to an assessment of the utility of union activity.14 Surprisingly and despite the revolutionary context of Lenin’s analysis, this pejorative interpretation of trade union behaviour has gained wide currency. Thus, economism and labourism have gained a bad name.

Sometimes economism and labourism are terms used interchangeably, despite the fact that for example, the latter concept embraces ideas about the role of government in supporting bread and butter unionism. Nonetheless there have been various attempts to describe and explain what trade unions usually do in positive terms15 – including some interesting Australian studies).16However, economistic trade union behaviour is frequently described in terms which suggest that myopic and simplistic attitudes to society dominate the attitudes and thinking of such unionists. This need not be so. Only if economism or labourism are defined as necessarily limited can the caricature be sustained. However, there can be sophisticated and unsophisticated union activity, sophisticated and unsophisticated labourism.17 Circumstances – including factors such as history, individuals, culture, the particular industry, skills and training of workers, the economic climate, the enterprise, investment potential and so on – will influence the origins and merits of particular strategies. In another sense, it might be added that it is scarcely imaginable that there could be any unions that would only concentrate on wages and salary matters without any regard for wider political issues, including bargaining laws, social security and broad economic directions. Those issues significantly influence the opportunities of workers and their families to live in dignity and prosperity. So, the roles that unions pursue in the economistic mould is not as barren as Lenin posited – between revolutionary and reformist poles. There is a great deal that unions can do within the labourist tradition.

Second, ‘strategic unionism’ seems to be a grand phrase to denote the kind of sophisticated trade union priorities and activities which well-resourced and ably staffed trade unions might pursue, specifically that experienced in the 1970s and 1980s in Austria, Sweden and Norway. It should be noted, however, that the experiences of unions in those countries in recent times has not been all sweetness and light. Unions everywhere face problems of organisation and relevance.18 In the early 1990s Scandinavian unions face the problem of a declining trade union base, albeit from a much higher level (some of if achieved in the 1980s) than in Australia.19 Technological changes and the dynamics of closer European economic relations were particularly important in Sweden in recent years in shaping the labour force and the policy directions of trade unions. Nonetheless what has been particularly noticeable about trade union organisation in the countries already cited has been the determination by unions to influence the broad parameters and details of public policy.20 This has been achieved not only through the resources available to unions and peak union councils – including impressive libraries, information systems, researchers, economists and other technocrats – but also through the merits of particular policies and the leaderships of organisations. In addition, the role of unions in those societies in providing welfare and medical insurance/benefits has been pivotal in influencing the degree of unionisation. Thus, unions have been concerned with economic changes, including relevant training and skills issues. Governments, unions and employers can create the socioeconomic environment in which businesses can grow and wealth be created. With growth in the right areas there will be growth in employment. And with appropriate productivity the work conditions for individuals should improve. But this improvement does not just happen. Sometimes it needs to be bargained for. Trade union strategies are usually advocated in the context of sharing the benefits from and the enhancement of economic performance and productivity. It could be argued, however, that what unions have attempted in those countries is similar to what unions have traditionally sought to do in Australia. Through the establishment of the Australian Labor Party and the continuing support for that party by many unions, it might be argued that all of the objectives stated as characteristic of strategic unionism in the above cited quote from the Australian Reconstructed report have been pursued in Australia through a combination of political and industrial means. This point leads to a consideration of what it is the ACTU has been seeking to achieve.

Throughout the life of the Accord the ACTU has sought to achieve several objectives: first, an incomes policy which leads to relatively predictable and stable wages growth; second, social wage changes – for example, in welfare, superannuation, taxation and training areas – which lead to improvements in the overall standard of living and greater equity and opportunities for employees, especially lower paid workers, social security beneficiaries and their families. This chapter, however, is not the place to canvass exhaustively the history and the development of the Accords between the ACTU and the Federal government.21

Several points are worth making here with respect to the experience since 1983, upon the election of the Hawke government: (a) the ACTU has become involved in the consultative process with the Federal government in a qualitatively different fashion than past experiences; this has involved a sharing of decision making processes and responsibilities and more detailed consideration by the ACTU of options available to the government; (b) by collectively acting to discipline the unions behind a centralised wage system (the broad outcomes of which, at least until the April 1991 National Wage Case decision, were determined by agreement between the ACTU and the Federal government) the ACTU secured an improved bargaining position with the government in achieving changes in taxation, family allowances, superannuation improvements, medical insurance and so forth.

In this sense the ACTU could be said to be pursuing the objectives of ‘strategic unionism’ – if by that phrase it is meant that the ACTU is working to an overall strategy, albeit a strategy tossed about, modified and reinvented according to changing economic and political circumstances. It might, also be noted that the idea of an ‘overall strategy’ exaggerates the ability of the ACTU leadership and unions generally to conceptualise detailed plans, about and rigidly work towards reconstructing Australian society. ACTU strategies in recent times, like many strategies, are improvised based on a mix of flashes of tactical brilliance, errors of judgement, opportunities of the moment, policy inspiration and the foibles of Australia’s economic performance. Whether the outcomes of the ACTU’s policy prescriptions and priorities have been successful is a matter of controversy. Success is an elusive term and is something that needs to be judged according to the possible alternative strategies, difficulties in implementation and unintended consequences. A recent criticism of the Accord processes can be found in Michael Costa’s and Mark Duffy’s (1991) Labor, Prosperity and the Nineties22 which raises a barrage of criticism about various aspects of the Accord – wage policy, union amalgamation, award restructuring and so on. But one error in the Costa/Duffy book is to assume the necessary and causal link between the Accord and Australia’s deteriorating economic performance in the latter part of the 1980s. Because the Accord originally championed the maintenance and improvement of real wages and because during the course of the 1980s this objective was not achieved, it may be easy to mock the Accord’s pretensions. But it would be erroneous to say that the strategy was a failure. After all, most unions knew what they were doing. Despite rhetoric about improving living standards, unions recognised, particularly after the deterioration of commodity prices in the middle 1980s, that a cut in living standards for most workers was inevitable. The Accord processes provided a way of managing that reduction in real wages whilst minimising industrial disputation. Would market forces rather than Accord agreements have been the best way to achieve those adjustments? Were the Accord processes good enough? Those are a few of the questions relevant to the debate as to whether the Accords were beneficial to Australians.

It is ridiculous to pretend in the early 1990s that the union movement is ‘rosy with success’ or that the Australian economy is buoyant and zipping away to new levels of productivity growth. Costa and Duffy are right to insist on judging policies on their merits and also according to their consequences (including their failure to anticipate and/or address certain problems and issues). But the jury needs to consider not only the words of policy against the economic performance but also whether modifications to the actual Accord strategies might have achieved substantially better results than that which might have occurred in their absence. Such modifications might still be consistent with an Accord approach. If a set of policies, A, are supposed to lead to consequences X, but actually lead to consequences Y, it does not necessarily mean that those policies were root and branch wrong. Perhaps if A were modified, the consequences would be different and more desirable. However, what is desirable is not a simple matter of dreaming or prescribing something and wishing it into reality. Most proposals need to be fought for to be realised, against other possibilities and forces within society. Failure to realise a goal may not have much to, do with the original idea. Many good ideas live in the minds of their adherents waiting for the moment of opportunity. Thus, even if the award restructuring agenda of the ACTU is badly flawed (as Costa and Duffy allege) it does not end the debate to say that the Accord is leading to a dead-end because of that. For example, modifications to the award restructuring agenda, including more attention to enterprise bargaining without strict bargaining restrictions, might still be compatible with the Accord processes. So, the strategic unionism of the Australian labour movement is not exhausted by whatever the policy prescription of the moment may be.

There is an aspect of the ACTU’s approach to strategic unionism which, so far, has only been touched on — namely, the so-called rationalisation of the structures of the union movement. One of the themes of the Australia Reconstructed report is that unions should be reorganised along industry lines and that the amalgamation of unions along such lines would ensure that unions would be able to better harness their resources to recruit members and service their existing membership. The Future Strategies document suggested that around twenty industry groupings might be the most suitable way to reorganise the union movement. The ACTU policy on the Organisation and Services of the Trade Union Movement emphasised the need to limit the number of unions at individual enterprises and within industries. The policy acknowledges that occupational unions may have a role in some industries, but the policy more favours industry unionism. Specifically, enterprise unions are rejected in the document as incompatible with strong, effective union structures.23 The policy document also emphasises the need for unions to be responsive to their memberships’ needs and stresses the importance of strong local workplace organisation. Thus, centralist and decentralist approaches are argued for — that is, better resourced, fewer, industry unions and decentralised union structures. Several points might be made about those policy prescriptions: (a) the Accord processes and this form of union organisation are not logically joined; thus it should be possible for a union or a unionist to be generally supportive of the Accord and critical/hostile to this form of union organisation; (b) nonetheless the Federal government by amending the industrial legislation to allow for easier amalgamation and, as well, transfers or changes in union membership at the industry and enterprise levels has supported the ACTU’s policies in this area. The rhetorical support of Ministers is matched by direct funding of unions by the government to assist in propagating a positive case for amalgamation; (c) the ACTU’s policy approach has arisen as a response to several factors: as a response to the argument that the union movement needs to be reorganised in order to be better able to market itself to potential members, as a means of assisting in the award restructuring/ industry flexibility processes and as a way to gather strength for the unions in their bargaining relationships with employers and governments; (d) whether or not the approach of the ACTU is correct is a matter of controversy.24

Some unions vehemently resent the consequences which have followed where they have been ousted or face pressure to be ejected from coverage in certain industries. There are winners and losers in changes which have followed, sometimes the same union has lost in some industries and gained in others. The ACTU attempted to resolve some of these tensions by inventing the concept of principal, significant and other union status within industries, where the principal union would have the primary responsibility of negotiating awards and agreements within an industry. Where occupational unions fit in to this structure remains problematical.

Will recruitment really increase? Are the unions reshuffling membership coverage amongst themselves rather than adding value to the unions’ ability to market and recruit? Is the strategy misguided, by assuming that economies of scale gained by mergers will lead to more attractive union structures? Are unions concentrating too much on the centralised structure and not enough on how to market — and what the marketing message(s) should be — to potential members? Will large, bureaucratic, unresponsive union structures emerge? Are significantly different strategies required for different industries, categories of workers and enterprises? These are some of the questions which require answers.

It is by no means certain that the ACTU’s strategies will lead to the development of more dynamic union structures and increases in union members. Personalities and human behaviour are frequently critical in shaping the success of policies and organisations, whatever the structures. The downward trend in union membership as a percentage of the whole workforce is an international phenomena replicated in nearly all advanced industrial societies.25 Those trends suggest that declining union density is due to factors such as drops in relative employment in manufacturing industry where union membership has been high; developments in the service industries and the rising percentage of workers in that sector (traditionally poorly organised) has meant that overall union density had to drop; middle class consciousness and satisfaction with conditions at the workplace have caused a reduction in the interest of workers to join a trade union; this latter fact is related to various developments, including the role of governments in defining and regulating rights at the workplace, the attention of management to consulting with and providing more benefits to employees and the successes of unions in overcoming the worse features of capitalism where some managers acted as unchallenged warlords.

One of the consequences of the debates within the ACTU, as well as the policies adopted by ACTU Congresses, has been the focussing of union leaders and members on what should be the future of their organisation.26 There are no unions in Australia which have not recently discussed amalgamation options and changes in membership coverage within industries. Some unions are enthusiastic supporters of this process. Others believe that ‘if you can’t stop it you may as well work the system’ and reluctantly court amalgamation suitors. But change is hastening.

Some of the opponents or just mere critics of the ACTU’s union rationalisation agenda are currently disadvantaged within the union movement by at least three factors: first, the proponents of the ACTU policy have been arguing for those changes for years. There were no challenges at the 1987 ACTU Congress to the Future Strategies document. By the time of the 1989 Congress the ACTU’s preferred approach received overwhelming endorsement. So, the intellectual challenge to the ACTU’s amalgamation/rationalisation approach has been late in coming; second, the ACTU’s agenda is said to be part of the new unionism — strategic unionism. Implied in this assertion is that the challengers do not believe in strategic unionism. Hardly anyone admits to not having a strategy. It is poor form — incoherent, directionless. Hence the rhetoric cleverly assists the proponents of the ACTU’s case; third, most unions seem prepared to give the ACTU’s policy a chance before adopting a more critical approach. ‘Let’s see what happens’, however, does not exactly summarise the attitudes of most union leaders. There is more to it than that. Most unions have merged or are merging and modifying their structures. This is mostly the behaviour of believers in the changes that are occurring.

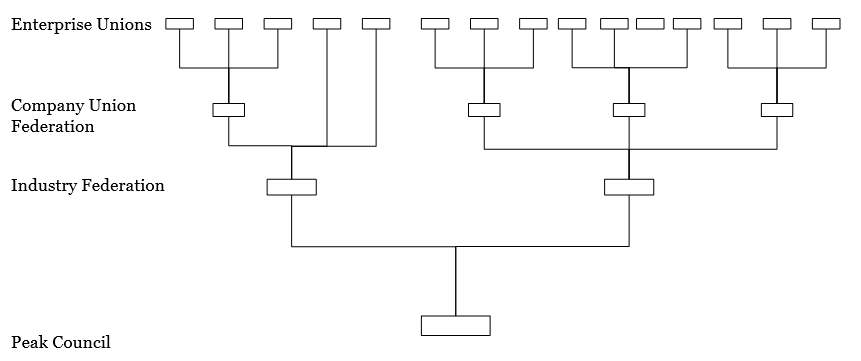

At first glance it might seem that Japanese industrial relations, especially the enterprise union structure, has almost nothing in common with those developments in Australia. Showing how false such an assessment would be is one of the issues addressed in this chapter. Before examining that topic, however, it would be advisable to explore various interpretations of Japanese industrial relations.

Interpreting Japanese Industrial Relations

Japan once interested industrial relations scholars as a rare example of an ‘intermediate’ society in the timetable of world industrialisation. In the mid 1950 it was possible to write

The average American who lives in Japan needs no authority to tell him that the Japanese industrial revolution has been uneven and, from his standpoint, drastically incomplete in some respects. These facts strike him forcefully and probably in irritating fashion when he loses some battle against substandard equipment (probably manufactured by a small plant or household deficient in resources and technique), or when he watches a worker pour first-grade packaged cement onto the ground, shovel an uncertain amount of water (and dirt) into it from the nearby gutter, and then proceed with the construction work. This same American will probably decry the excessive number of workers assigned to most tasks and the complex method of wage payment which seems more paternalistic than efficient. Yet, at the same time, he will take pride in his Japanese camera, he will enjoy riding home on an ultra-modern Japanese steamship, and he can scarcely fail to note the major feats of Japanese heavy industry where productivity increases have recently been surpassing those of almost every nation in the world. If it is easy to suggest some strengths and weaknesses of Japanese industrialisation in such simple terms, it is vastly more difficult to subject them to a painstaking and balanced analysis that seeks out causation, weight and interrelationship.27

In those days Japanese unions believed that reaching the wages level of the US and European workers, still less achieving the technological advances achieved in those countries, would have been like touching a twinkling star in the sky.28

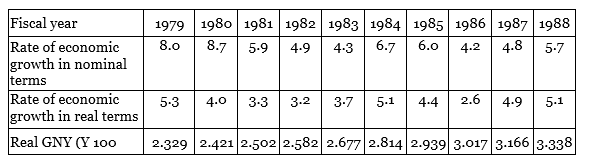

However, in the last three decades the economic successes of the Japanese has excited a great deal of interest; the contribution of labour relations to those achievements has received particular attention. Diagram 2 highlights the Japanese achievements in economic growth in the decade 1979-1988. Nothing excites so much respect as success. This is not to say that all of the interest in Japanese labour relations has been uncritical or merely of the instrumentalist kind that seeks to uncover the three or four keys to the ‘miracle’. Much of the attention of critics and friends has been sharp and searching — in other words, and in the best traditions of that term, critical of those developments.

Diagram 2: GNP and Rate of Economic Growth in Japan, 1979-1988

Source: Nikkeiren; Economic Planning Agency, Annual Report on National Accounts.29

The characteristics frequently highlighted in the literature on Japanese industrial relations, namely the three ‘sacred treasures’ of lifetime employment, seniority based wages and enterprise unionism are described by Moore (1987) in an article on Japanese Industrial Relations’ in negative terms: ‘. . . the three treasures are really the treasures of management, not of labour in the broader sense; and they have served management well by securing for it a degree of cooperation from its unionised employees that is the envy of the entire industrialised world’. Moore also argues that:

Japan’s largest enterprises have been so successful at mobilising their permanent employees behind a drive for seemingly impossible increases in worker productivity without provoking industrial strife that businessmen and government officials, almost everywhere are seeking to restructure labour relations in their own countries on what they take to be the Japanese system. All too often they are drawing lessons from a stereotyped and superficial understanding of Japanese labour relations perpetuated by experts more interested in efficiency than in such goals as a more humane workplace.30

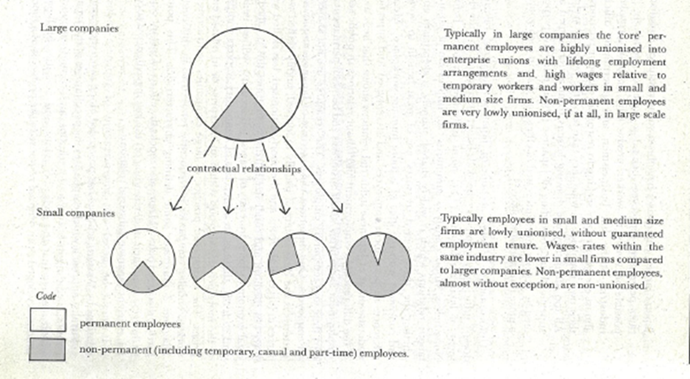

Unfortunately, Moore’s account of Japanese industrial relations does not sufficiently emphasise the skills-based orientation and development of labour relations. (This point is further explored below). Nonetheless Moore’s analysis summarises an impression of Japanese labour relations which is widely shared: namely, a scepticism about whether the ‘three sacred treasures’ are of great benefit to workers and consistent with the idea of ‘a more humane workplace’. Moore’s references to ‘permanent employees’ and ‘stereotyped’ and ‘superficial’ understandings of Japanese industrial relations shows that he is aware of the differences in employment and labour relations in public sector employment, large firms, small businesses and between permanent and part time and temporary employees. The ‘treasures’ are not shared by all employees. One important characteristic of Japanese employment patterns is the dual system of usually unionised, highly skilled workforces in larger scale firms and the poorly unionised, less skilled workforces in medium and small sized firms. Sometimes this is called the dual economy where, in terms of wages, job security, welfare benefits and so forth, there is an underclass of temporary workers compared to the more privileged group within an enterprise or in related enterprises. The widespread practice of large companies contracting out work to smaller companies is frequently referred to in this context. Diagram 3 illustrates some defining characteristics. This point is further discussed below. Moore also mocks the efforts of instant experts to describe (and their understanding of) the key ingredients of successful, efficient Japanese industrial relations.

It might be noted that interpretations of Japanese industrial relations by Western scholars has proceeded along two axes: namely a culturalist approach which emphasises the peculiarities of the Japanese culture, including its history and traditions, and, second, an approach which is stresses that the style, behaviour and activities of Japanese unions developed as an original response to the problems of a modern, technologically sophisticated society — and that this model is adaptable to other countries, including advanced Western Societies.

Diagram 3: The Dual Economy

The various interpretations that are offered is a bit like seeing Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon movie.31 (That is a film about various characters who, whilst seeking shelter from a rainstorm underneath the semi-ruined Rashomon gate, describe what they saw and understood about the murder of a samurai warrior. In the flashbacks which show what each of the characters — a priest, a woodcutter and a commoner claim to have seen — and that of a fourth man, Tajomaru, a bandit executed for the crime, it is obvious that there are contradictions in explanation and evidence. Nonetheless each of the four interpretations seem separately plausible and it is hard to tell which is true and what might be partially accurate. That is the mystery and the achievement of the film).

Rather than exhaustively exploring the history of interpretations of Japanese labour relations (something not only beyond the scope of this Chapter, but also beyond the competence of the author) it might be useful to note a few studies.32 J.C. Abegglen’s The Japanese Factory (1958) emphasised the virtues of cultural continuity, groupism and lifetime employment as keys to the organisation of work in Japan and discussed in the development of the harmonious idea of labour relations based on cooperation between workers and management.33 Interestingly, Abegglen suggested that although Japanese culture and traditions were critical to the types of unions which were formed in the 1940s and 1950s — that enterprise unionism, for example, was more attuned to the outlook of Japanese workers compared to other forms of organisation, such as industry unionism — he also thought that as industry continued to develop the practices of lifelong employment, seniority based wages and enterprise unionism would be discarded. Abegglen revised those views in a subsequent book on Management and the Worker: The Japanese Solution (1973).34 S.B. Levine’s Industrial Relations in Postwar Japan (1958) explored the development of enterprise unionism and the competing ideas within Japan — between unions, management and government as well as within unions — to determine the shape of labour relations in the late 1940s and 1950s.35 Both books featured the Japanese enterprise as the location of worker organisation and solidarity and highlighted differences in American union organisation compared with the Japanese experience. Both books became famous in the West as interest grew in the economic successes of Japan. Popular and shorthand interpretations — such as those referred to earlier by Moore — tended to emphasise the three sacred treasures to the exclusion of everything else. However, it would be as fair to judge Levine’s and Abegglen’s differing interpretations according to the bowderlised summaries as it would be to assess the literary achievements of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House or Shusaku Endo’s Samurai according to someone’s summary of cribs of those books.

Earlier this Chapter noted that the story of industrial relations in a society such as Japan must be regarded as complicated and infused with factors which indicate that patterns of behaviour by no means imply total uniformity. This does not mean that it is impossible to describe the industrial relations system of Japan. Clearly there are various characteristics, organisations and behaviour which typify and sometimes dominate that system. What follows is a brief sketch of what might be called the Japanese industrial relations system.

Solomon Levine (1982) in a review of the literature on Japanese industrial relations comments that:

A national system is so complex that it is largely abstract even to talk about a national system. Within each nation there is likely to be a large variety of sub-systems, each of which may be different from the others — ranging from industrial to workshop levels. This is all the more reason why it is inaccurate, if not dangerous, to attach stereotypes to a national system of industrial relations, or to declare that a national system, such as Japan’s, is totally unique compared to other national systems, while the comparison of national systems tends to highlight the differences among them; but if they are broken down into their sub-systems, the sub-systems, especially at a common industry level, often become highly similar from country to country.36

Levine’s comments are a useful caveat concerning the interpretation of Japanese labour relations. Rather than teasing out all of the environmental, technological and organisational issues associated with this topic, this paper will focus on and briefly discuss (a) some of the major features of the Japanese economy; (b) the main characteristics of Japanese labour relations, including some differences between large, medium and small size firms; (c) the methods of wage determination, especially the Shunto process; and (d) some economic issues which have decisively shaped labour relations in Japan.

Ronald Dore (1987) has listed eleven ingredients which distinctively characterise the Japanese economy:37

-

- The Japanese work hard.

- The Japanese are well educated.

- Japanese work cooperatively in large corporations.

- There is extensive use of subcontracting in manufacturing.

- Japan has a managerial, production-orientated capitalism, not a shareholder-dominated form of capitalism.

- Japan has the most effective form of income policy outside Austria and Sweden.

- Japan has a high savings rate and low rates of interest and her corporations invest 15 per cent of GNP, as do government and households combined.

- Japan is still a relatively ‘small government’ country.

- Japanese corporations are very good at forming cartels.

- The Japanese value and honour the public service, and an intelligent industrial policy is one consequence of this.

- By contrast, the Japanese do not much honour politicians, whose role in running the economy is small.

In addition, Japan is characterised by strong competition between firms. By simply listing these points they may appear unsubtle and too sweeping as legitimate conclusions applicable to the Japanese economy. Nonetheless there are three defences for this summary appearing here: first, there is a limit to how much this chapter can explore with respect to economic issues relevant to an understanding of Japanese industrial relations; second, Dore’s work is based on a good deal of empirical work as well as theoretical inspiration. An explanation and justification for the above-mentioned points can be found in Dore’s numerous publications on Japan;38 third, the points raised by Dore are probably true and – therefore worth stating! Each of the eleven rubrics can be justified. The statement that ‘Japanese work hard’ is obviously a generalisation, but also an accurate one. Japanese on average work much longer than workers in other advanced industrial societies.39 Further, the Japanese on average spend longer periods at school (in terms of hours of attendance ) and in post-school educational experiences compared to most other nations — and so the summary could go on. Having asserted those facts, it might be useful to now examine in more detail some of the interesting features of industrial relations and trade union behaviour in Japan.

Kazuo Koike (1988) in an important study, Understanding Industry Relations in Modern Japan, has critically examined interpretations of Japanese employee relations which glorify the three sacred treasures which emphasise the so-called uniqueness of Japanese culture.40Koike comments that:

…the culturalist thesis which stresses that Japanese systems are unique has tended to predominate. This interpretation has prevailed because of an undue reliance on the neoclassical theoretical framework. Under such premises a worker’s enthusiasm for small group activities does appear to be really strange. The neoclassical theory of perfect market competition requires that when the company is on the downturn of a business wave either surplus labour is made redundant or wages are cut so that labour voluntarily moves away. If, on the contrary, the company’s results exceed those of its competitors, because there is no theoretical rationale for raising wages beyond the ruling market rates, surplus profits naturally are paid out in dividends or invested in plant and equipment. Therefore, under neoclassical economic theory, there would be no incentive for the company’s shop floor workers to engage in activities geared towards raising productivity. When workers do display a technical aptitude for improving production methods, would they be so stupid as to be tricked by the management into engaging in such activities? Consequently, this apparently odd behaviour of Japanese workers supports the culturalist thesis that Japan’s culture is unique.41

But there is a gaping flaw in such a thesis, as Koike explains in his book. Just because particular aspects of reality do not conform to the neoclassical world view, this does not mean that particular aspects are odd or exceptional. Perhaps there is something wrong with the theory. The economist Alec Nove, referring to the unreal explanations of perfect competition and the workings of firms, once joked: ‘Comically enough, this dry-as-dust construction was described by some Marxists as “apologetics for capitalism”, although, apart from its inherent reality, it proposed no real role for capitalists, and treated everyone, capitalists and workers alike, as automata reacting to stimuli under conditions unknown in any world yet encountered.’42 Koike contests the highly abstract theoretical model that claims that market competition purely determines that wages are paid on the basis of performance alone. He poses the question as to why ‘the certainty of the culturalists without, adequate comparative empirical research?’43And Koike argues-that permanent employment, seniority wage systems and enterprise union structures are much more common in the West than is commonly supposed. Thus he claims ‘. . . international comparisons are implied, but then the implicit standard of comparison is usually not reality in the West, but theoretical depiction.’44 In part, Koike can make this judgement due to the fact that his opinions are informed by a wealth of empirical research both in Japan and in other countries, such as the United States.

What are the main conclusions of this research? Here is not the place to attempt a full-scale review of this work. But these observations seem particularly fruitful for an appreciation of Japanese industrial relations:

-

- The white collarisation thesis: (a) blue collar workers in Japan may be just as skilled as white collar workers; (b) the possession of wide ranging skills by some blue collar workers and the narrowing of wage differentials, can engender egalitarianism; (c) welfare benefits are provided to blue collar as well as white collar workers.

- The formation of skills is primarily a function of on the job training (usually experienced within the company). Thus, the development of technical skills and flexibility in work design and inventiveness is related to training and length of service in an enterprise. Thus, permanent employment patterns are a logical response (rather than a cultural mystery) to the need of an enterprise to prize and retain individuals with skills that may not be easily purchased in the labour market.

- So-called seniority wages are not a unique feature of Japanese wage systems. ‘The upward slope of the age-wage profile up to the 50-year old age group is not just confined to Japan, but is common to male white-collar wages in the EC, the USA and Japan. Instead, the distinct feature of contemporary large Japanese companies is that age-wage profiles for blue-collar males are also upward sloping.’45 Generally, the longer an employee has worked for a company (the more senior he or she is) the higher the wages paid to that employee.

- Although there are many similarities in industrial relations patterns in the US and Japan, such similarities mask important differences. Thus even if workers’ careers in the steel industry, for example, are partly characterised by wages systems reflected in collective agreements emphasising seniority there is a striking difference with the Japanese pattern: ‘whereas the collective agreements emphasise ability, qualification and fitness, in practice rigid, indisputable rules based on the relative years on service in the workplace have been established’46 in the United States. Thus, the seniority principle becomes rigidly paramount in many US collective bargaining agreements compared to Japanese experiences in the same industry.

- In large firms, enterprise unions (normally only representing permanent employees) predominate. They actually have real power particularly with respect to job transfers and promotions.

- In large firms quality circles (QCs) are common not only because they provide a vehicle for workers to express opinions on improvements in work arrangements and as a consultative mechanism (too much of the literature just emphasises the ‘touchy/feely’ aspects of worker participation) but also the technical background and the wide ranging skills possessed by employees. Significantly, as a general rule, the popularity, of quality circles considerably diminishes the smaller the firm. This is because the skills possessed by employees in small firms and the opportunities to upgrade skills and experience varieties of work experience is much less. Koike points out that quality circles require workers to have a good understanding of the production process; for example:

Let us take the example of a large and complex machine being operated by the workers apparently simply pushing buttons and pulling levers. Yet the workers have to understand the machine’s operations in order to be able to improve their productivity. Another more specific example of a QC circle’s success took place in an automated workshop for wrapping sausages. The workers had been aware that the defect rate for imperfectly wrapped sausages consistently remained above zero. The QC circle found that imperfect wrapping resulted from the sausages bending on account of heat. Corrective measures required, therefore, that the heating treatment of the sausages should be adjusted not only in this QC circle’s workshop but also at the earlier processing stages. Thus, to be able to engage in effective QC circle activities workers have to understand the production process in a wider sphere even than their own workshop.47

Thus, besides such technical competence, there are three other criteria explaining the successful operation of QCs: as a means to try out new ways of raising productivity, as a means of raising employment benefits (available through productivity gains) and as a framework for ensuring workers gain from the improvements to which they have contributed.

-

- Work patterns in smaller and medium size firms are much more, diverse than in larger firms. At least three schema might be described: (a) where work and skill patterns are similar to larger firms but where progression and career opportunities (especially for blue collar workers) are more limited than in larger firms; (b) where the enterprise is confined to just one workshop or workplace. Hence the ‘workers in this group do not have any further opportunity to widen their skills because the workshops are generally smaller than in a large company. This group — for which an appropriate label might be “shallow internalisation type” — accounts for the majority of workers in small and medium-sized companies’;48 (c) there are the unskilled and part- time workers. Even though the wage profile over all three groups falls below that of large-scale companies, the workers in the first two categories acquire a broad range of skills (even if the skills of the majority are shallower).

- Enterprise unions in Japan are in some senses akin to local unions as they operate in the United States. There the bargaining agent is the local union which has achieved bargaining unit coverage (which may include the whole of an enterprise). Though there are important differences. For example, the American union will usually cover part-time and non-permanent employees; but managerial workers (including foremen and supervisors) are usually excluded from the bargaining unit.49 In contrast, it is not usual for a Japanese union to cover part time and non-permanent employees; frequently foremen and supervisors are members of the union -in a large enterprise in Japan.

- The ability of white collar and blue collar workers to conceive a good plan, to persuade and to have characteristics of combining the strengths of strategic ability and combativeness are important to promotion. Thus Koike, concludes that a white collar worker seeking promotion:

… must have a keen insight into his own complicated organisation, including in particular the informal structure as well as the formal one. To put his plan into effect, he needs to know who will be the key persons in its implementation, and where to begin prior to consultation on his plan. This process of prior consultation and interaction between managerial personnel is known in Japan as nemawashi (literally: digging round the roots).50

-

- Both large, medium and small scale firms utilise consultative mechanisms with their employees. Thus, Koike observes that the German work councils have affinities with the Japanese experience where both unionised and non-unionised workplaces commonly have such structures. Nikkeiren estimates that as at the middle of 1987, 84.2 per cent of enterprise unions had some kind of joint consultative body.51

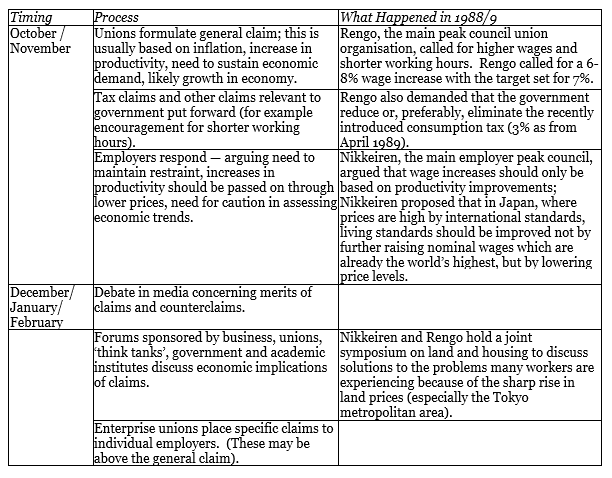

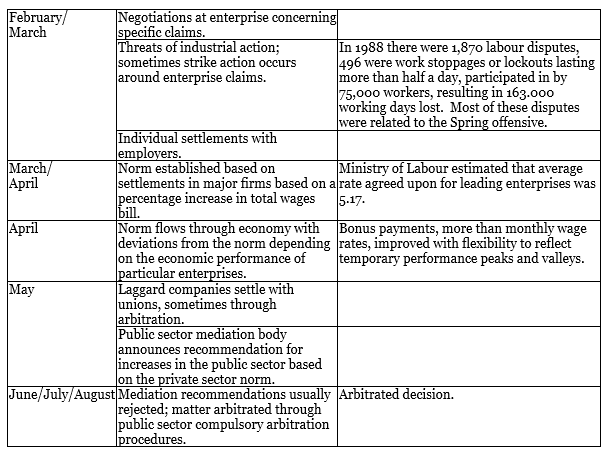

In summary, many of the myths and common interpretations of Japanese industrial relations are cut down by Koike’s analysis. Perhaps one of the most important findings of this study is the skills linkage between labour and union organisation. Thus Koike concludes that: ‘Insofar as there is any special characteristic belonging to Japanese unions it lies in a different aspect: the union’s interest and voice in a wide area of managerial affairs.’52 This has important implications for work organisation including flexible and productive changes in work practices. Before developing those points, it is appropriate to note that conflicts between unions and management have not been spirited away in Japan. The annual negotiations around wage increases illustrates that point. The Shunto or Spring Offensive or even Spring Negotiations as, in the industrial relations quietism of the 1980s this process has come to be known, works as follows. In November/December of each year unions launch campaigns about increasing wages by publicly declaring what wage increases should be merited in the coming year. Those claims are related to a basket of economic factors including movements in prices, the state of the labour market, productivity and GDP growth. A general claim is made by the unions (usually by February) and negotiations focus around that. Enterprise unions lodge specific claims with employers. Those claims are based on the general overall claim and are modified according to variations (such as productivity and profitability) at the individual enterprise. In fact, the enterprise unions are fairly autonomous in determining their own wage settlements. By March settlements in various enterprises have occurred and it is possible to estimate the average settlements — this establishes a quasi norm which is further modified according to negotiations in the Spring. The resultant norm flows to most of the rest of the private sector. In recent decades settlements in the large automotive, machine tool, steel and electrical industries have largely shaped the norm. The flow through of the Shunto settlement usually occurs in May when

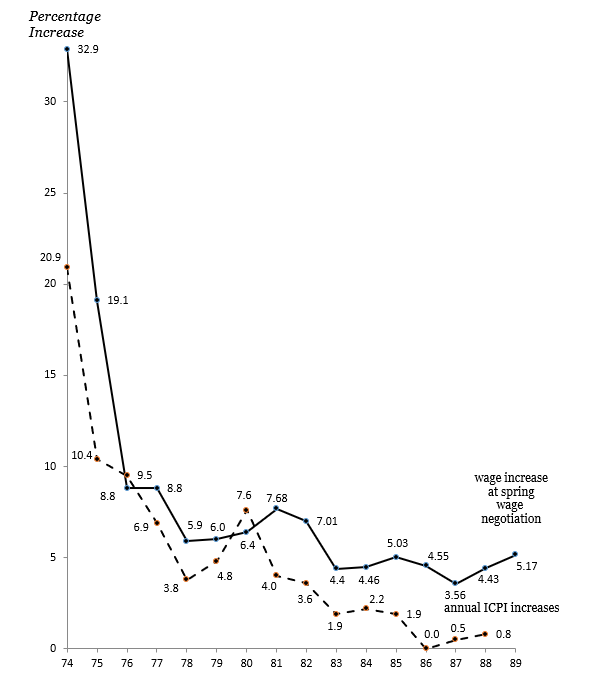

Diagram 4: Annual Changes in Prices and Spring Wage Increases, 1974- 89

Source: Nikkeiren; Japan Ministry of Labour53

Table 1: SHUNTO or Spring Offensive54

most of the large companies have reached agreements. Smaller firms pay wages based on a percentage of the wages paid to workers in the larger firm. Settlements around the norm are usually flowed on to all — but discounting or additions due to the economic factors within an industry or enterprise or region also occurs. The public sector usually adjusts its wages in the August after arbitration based on a consideration of the wage variations in the private sector and factors relevant to public sector employment. Table 1 provides an indicative chronology as to how the Spring Offensive usually works out, with reference to what happened in 1988-89. Diagram 4 shows the annual movements in prices compared to the Spring Wage increases between 1974 and 1989. Wage increases were usually above movements in the CPI, reflecting the bargaining successes of the unions and the strong productivity growth in Japan. A comparison between this diagram and Diagram 2 illustrates that wages growth was not merely a combination of CPI plus productivity. Improvements in productivity have been passed on not only through higher wages but also in improvements in quality, lower prices, higher profits, new investment and so on. In the latter part of the 1980s wages growth has closely matched rises in economic growth.

In the 1980s this system of wage determination has worked in a relatively orderly way. However, this was not always so. In the mid-1950s when the Sohyo unions55 pioneered the Spring Offensive (and especially in the decade before), conflicts between unions and management were frequently fierce and intense with substantial losses in industrial time. Indeed, the idea that Japanese industrial relations has traditionally worked along harmonious lines is a myth.

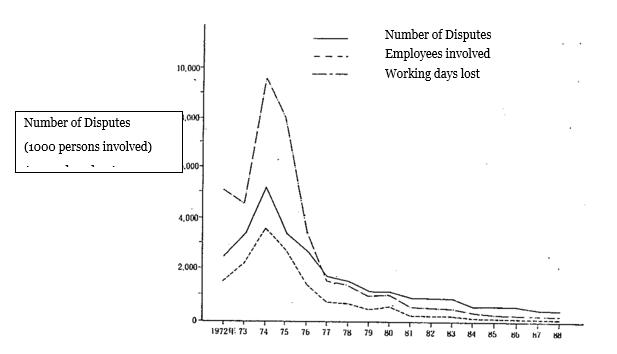

Diagram 5: Trends in Industrial Disputes 1972-1988

Source: Ministry of Labour, Labour Disputes Statistics; Nikkeiren. This chart is based on information about work stoppages or lockouts lasting more than half a day.56

Yasuo Kuwahara has emphasised the conflict laden characteristics of Japanese industrial relations over much of this century

At the end of the last century, an iron workers’ union was organised, the first modern-type labor union. The prewar period saw a series of violent labor disputes and merciless oppression. In the postwar period, labor unions took up where they left off, and there were again repeated disputes until the 1960s. These often bloody encounters were far from the ideal of ‘cooperative’ industrial relations.57

Some of this conflict, especially in the immediate postwar years, involved contests between left and right within the Japanese labour movement, including struggles relating to the form of union organisation. Koike also points out that, especially in the period up to the middle 1970s, Japan’s level of industrial disputation was similar to the levels experienced in France and Britain. Thus, another myth — that Japan has hardly had any industrial troubles — crumbles against the empirical evidence.58

Nonetheless from 1974, in the midst of the oil crises engulfing the world, a substantial change came about in Japanese industrial relations as Diagram 5 indicates. Industrial conflict lessened considerably based on numbers of disputes, employees involved and the working days lost.

What happened? In part there was a reaction to the shock of rapidly increasing inflation and sharply increased industrial conflict; a continuation of those trends meant that Japan was in danger of eventually pricing itself out of world markets. Accordingly, representatives of government, employers and most unions warned about the dangers of spiralling inflation and wages growth many times ahead of productivity, and, importantly, well-above the average of the OECD countries. This was an important factor in the tempering of expectations in the Spring Offensive in 1974 and subsequent years. (Thus, it can be argued that the Shunto process, by providing means for canvassing the economic merits of claims and counter claims at the national level, encouraged a high degree of understanding as to wider economic implications of steep and continual increases in wages and inflation). However, the consensus by the elites was not enough.

In an article reflecting on the changes that occurred in the middle 1970s, Hideo Ishida (1983) asserted that:

… a consensus at the national centres level could not automatically bring about a decline in the rate of wage increase. Rank- and-file workers might have revolted against union leaders and gone on wildcat strikes. To be sure, the prevailing atmosphere that the Japanese economy was in a very precarious situation caused a sharp decline in wage aspirations. What was more important, however, was the recognition that the companies were in difficulties and that workers should refrain from asking for big wage increases in order to prevent their enterprises from going bankrupt. On the other hand, management earnestly requested both union leaders and employees for unified efforts to overcome difficulties, and this request must have struck home.59

Thus, the argument is put that the enterprise-based location of union organisation was significant to the achievement of that consensus. Just how significant is not easy to judge. It would be hard to demonstrate that only enterprise union structures could achieve the critical consensus required. Also significant were the promises of the major employers to restrain price increases and the government to support the general policy of ‘restraint’, including limits on increases in government taxes and charges. The informal process of coordination of national wage settlement was formalised through a Wages Council after the 1974 wages explosion. The subsequent withering away of industrial disputation, as illustrated in Diagram 5, is due to the surge in economic growth by the Japanese companies, the sharing of the benefits of that growth and, perhaps, an indication of the potential power of trade unions. It should not be assumed that the pattern of industrial disputation is a weathervane of union power, strength and influence. There is the argument that a strong organisation does not have to force industrial action in order to achieve its aims. Nonetheless the experience in the early 1970s (the first oil shock was in 1971) and in 1974 was a salutory reminder that the Japanese economy, more than most, was vulnerable to unfavourable trends in world trade. The competitive environment in which Japanese firms in the tradeable goods and services sectors operate is an important explanatory factor for an assessment of employee relations in Japan.

Iwao Nakatani (1991) in a paper on ‘The Nature of “Imbalance” Between the US and Japan’ argues that the huge divergence between the US and Japan in their economic performance is due to different models of economic activity and structures: ‘…the core idea underlying Japanese-style capitalism is networking, while the essence of western capitalism, especially of American-style capitalism is found in the concept of the market…’60 Nakatani develops this idea by comparing corporate behaviour and the relationship of businesses to capital markets in both countries. He suggests, for example, that the relationships established by small firms and the larger core company are significantly different in both countries. In Japan a network of long term relationships are established with interdependent companies based on confidence that the long term business future with the parent company is assured. In contrast, there is the gruelling and uncertain American system. Contracting out of work, for example, means different things in each country. Nakatani suggests that Japan’s most internationally competitive industries electronics and machine tools — have obtained significant competitive advantage through this closely knit cooperation with dependent companies. He doubts that ‘If contracts were renewable on a yearly basis and there was no guarantee of a long term relationship, parts manufacturers would not be so ready to invest the time and money this system necessitates.’61 In contrast, he claims that:

… American-style capitalism is deeply rooted in the short-term market-oriented thinking that you buy from whoever is offering the best quality and price. The essence of American-style capitalism is that if a competitor of the company you are doing business with comes up with a better deal in terms of price or quality, you do not hesitate to change partners. Although this practice has played an important role in making the American market open and competitive, it has at the same time proved a barrier to setting up systems like the JIT inventory system which depend on close cooperation between companies. Under a market-orientated capitalist system, parts manufacturers naturally ask themselves why they should go the extra mile when there is no guarantee that they will be doing business with the same company the following year.62

This can have substantial consequences in industries producing, goods — such as the modern car — containing thousands of components. Lower inventory costs, flexibility in the obtaining of parts, creativity in the fashioning of new designs, gadgets and additions, technological improvements and just-in-time production processes are critical factors endowing a motor vehicle plant with comparative advantage. To those factors might be added stable employment patterns, skilled employees and predictable, cooperative industrial relations.

Nakatani comments:

Recently, after an inspection tour of US and European car plants, an executive with a Japanese car manufacturer commented that the era when Japan stood unrivalled in the industry had arrived. This was not mere boasting. An article in a recent Business Week entitled ‘New Era for Auto Quality’ (22 October 1990) comments:

Uh oh, Detroit, watch out. Once again something extraordinary is happening in Japan. Just as US car makers are getting their quality up to par, the Japanese are redefining and expanding the term. The new concept is called miryokuteki hinshitsu — making cars more than reliable, that fascinate, bewitch and delight.

Without going this far, it can be said that the gap between the two countries’ auto industries has widened greatly. After I graduated, I worked for a car company for a few years. In the late 1960s, the Japanese did not dream of attaining the heights reached by the American auto industry. The difference between an American car, accelerating easily up the steep streets of San Francisco, and a Japanese car, struggling to maintain speed even with the accelerator pedal pushed to the floor, was one of quality and not one of engine capacity. Now the situation has been totally reversed.63

How? Why? David Friedman in an influential (1988) study on Japanese industrial development and political change, The Misunderstood Miracle, argues that the Japanese attention to flexible, innovative production has allowed Japan to score so successfully in world economic performance.64 This interpretation rejects the arguments that Japan’s performance can be explained according to what he calls the free market regulation thesis or the Chalmers Johnson-MITI-bureaucratic guidance thesis.65 Friedman argues that:

…both the bureaucratic and the market regulation theses assume that Japanese industry is basically the same as elsewhere, only more efficient. By contrast, I argue that Japanese industry diverged from other cases: the flexible manufacturing option was developed more fully in Japan. I challenge both the claim of the bureaucratic regulation thesis that the state coordinated the attainment of greater efficiency in Japan, and the contention of the market regulation thesis that competitive cues alone led to an optimal outcome. Rather the cumulative effect -of political! developments throughout Japanese society made it impossible for the state to coordinate the economy as bureaucrats wanted; at the same time those developments also provided the political, social, and financial prerequisites for the competitive market behaviour that the Japanese exhibited. That is, the bureaucratic regulation thesis is substantially wrong, the market approach incomplete. It is only by viewing Japanese development as the consequence of myriad political struggles affecting industrial rights that important features of the Japanese industrial system may be addressed, let alone explained.66

Friedman attempts this explanation through a detailed assessment, from the 1930s to the early 1980s, of the development of the machine tool industry, including numerically controlled machines, and small scale manufacturing related to those industries. He shows that the typically American approach of gaining competitive advantage through mass production is flawed. In an ambiguous assessment Friedman asserts that: ‘Choosing a type of production depends on how people evaluate the market context around them, but they have no guarantee that they interpret that context correctly. Industrial choice cannot be reduced to the inevitable discovery of the optimal production solution in the face of Darwinian competition.’67However that assessment is – ambiguous because the analysis in The Misunderstood Miracle suggests that competitive advantage is achieved through flexible, innovative and well-designed changes; furthermore, the mutation of products j and work organisation are critical to the achievement of that advantage.

The theoretical work by Piore and Sabel (1984) in their book on The Second Great Industrial Divide is utilised by Friedman.68 Piore and Sabel argue that political factors are crucial to a country’s industrial development; shared ideas concerning justice and fairness or a governing consensus about such matters are essential to an understanding of economic development within societies. Thus, Friedman argues that:

The ideas workers develop about fairness in the factory, for example, will constrain or enhance trust between managers and employees. Combined with the ideological residue of countless other political battles such ideas will lead to greater or lesser incentives toward mass or flexible production. Workers in one setting may fight to preserve their place in the factory through the retention of specific job classifications, thereby making the attempt to redefine work continually, as in flexible production, more difficult. In similar circumstances other workers may see one of their essential rights as being able to learn new work and plan factory operations autonomously, making it more likely that some sort of flexible production would develop.69

In part this explanation has affinities with Ronald Dore’s (1987) study on Taking Japan Seriously, which is discussed below. Thus, the political issues discussed by Friedman have significant consequences for industrial relations, including the characteristics of trade unions with respect to negotiations, conflict and the issues to be encompassed in the union’s role in the employee/employer relationship. Although Piore’s and Sabel’s thesis — that the second great industrial divide will be between enterprises, industries and nations which encourage consultation, high skills, autonomous work groups and flexible work organisation — seems so idealistic as to be romantic, many (though not all) the developments in work organisation in Japan seem to corroborate their thesis. Even if it is premature to write about the end of Fordism and Taylorism in all industries, in some industries in Japan it is possible to write that obituary. It is, however, highly unlikely that all work situations will ever be characterised by cheerful, autonomous workgroups.70

The idea that Japanese workers are merely compliant sponges soaking up management directives and routinely going about their tasks is contested by David Friedman in his study:

Even liberal and radical observers have reluctantly concluded that economic efficiency demands the subordination of goals of equality, wage support, and the like. As a result, policy debate frequently focuses on reforms designed to curb political or social freedoms or to limit economic rights that, it is feared, may restrict business activity.

Japanese experience challenges this view. First, in flexible production some of the perceived trade-offs between efficiency and specific social objectives are reduced. As we saw in Sakaki [a township in Nagano Prefecture which was transformed from a poor agricultural village to one of the world’s largest users of numerical controlled machinery], a competitive flexible industry is not inconsistent with either equality or wage support goals. Indeed, high wages and increased managerial or self-employment opportunities were crucial to the labor and inter-firm trust that made flexibility possible. Firms could offer higher wages because they were building products for consumers with specialised needs who were willing to pay more for individually tailored goods. Equality of opportunity in the factory and between firms was essential to the high skill and worker autonomy that facilitated rapid production shifts. To the extent that American policies sacrifice social objectives consistent with flexibility, they reduce the potential for manufacturing revival.71

Important to an assessment of those claims is an appreciation of notions of fairness. Table 2 summarises some ideas about fairness at the workplace. Differences in adherence to one or other or combinations of those principles is influential in deciding patterns of behaviour. For example, adherence to equal pay for equal work is a reinforcing principle of industrial relations where union organisation is along craft lines. Thus, it is a familiar thing that most Australian unions will strive for wage justice where everybody receives about the same wages and conditions depending on their classification. Thus, the metal workers, unions insist that the Metal Industry Award be applicable across the whole of the industry (but this does not exclude — especially in recent times — over award payments and/or enterprise agreements above the award rate). The principle of equal pay for enterprises of equal standing is commonly understood and applied in Japan but not so widely in Australia. Thus, the idea of wage justice can mean different things depending on what notion of fairness is supported. This point clearly illustrates that the political economy of Japan is tied to ideas relevant to equality and what is ‘reasonable’.

Within Australian society it is sometimes said that one of the great achievements of the trade unions has been the fostering of equality at the workplace. Table 2 requires that such claims be subject to a more complex assessment than is usually the case. Also, it might be stated that even if the mean relative disparity between wages in Australia is not as great as most other countries, this does not warrant the comfortable assertion that Australia is an egalitarian society. ‘What is the best measure of egalitarianism and equality of opportunity?’ is no easy question to answer. Where there is a huge disparity in the skills possessed in a workplace, where there are few opportunities to upgrade skills, where consultative procedures are primitive or practically non-existent, does it make much sense to argue — because the relative differences in wages paid to the production workers, maintenance crews, foremen, administrative workers and the managers are not severe — that this is an egalitarian workplace? It would be an odd conclusion to so argue.

Perhaps one of the most interesting issues relevant to the Japanese experience is how large organisations, especially, have produced flatter management structures, highly skilled employees, and consultative structures which, arguably, have combined to promote not only a spirit of fairness and equality but also a determination to maintain personal and group efforts at skills acquisition and to reach for new levels of productivity improvements. In all those senses do Japanese workers identify their responsibility for cleansing the rust from the operations of the enterprises which employ them.

Table 2: Notions of Fairness

| Idea | Implications |

| Equal Pay for Equal Work (EPEW) | Each person in a firm is paid as much as people doing the same work in other firms. |

| Equal Percentage Pay Increases for All (EPPI) | Each person’s job is paid according differentials based on skills, difficulties, training, experience and so on. (This does not mean the relative differentials are fair). Thus, EPPI means equal percentage pay rises for all, unless for some good reason. People learn to live with existing differentials over time, and any disturbances thereof usually strikes the relative loser as unfair. |

| Equal Shares in the Fruits of Shared Effort (ESSE) | When an enterprise does well, all of its members should do well. Thus, ESSE means that, in good times, higher than average production should be reflected in higher than average dividends and in higher than average wages. |

| Equal Treatment for Same Contribution (ETSC) | This might be defined as the ‘no loss principle’, that everyone has a right to be compensated for rises in the cost of living. ETSC means that if there has been no diminution in our contribution to the firm there should be no reduction in our real reward. |

| Equal Pay for Enterprises of Equal Standing (EPEES) | This is a principle applicble to an economy, like Japan’s, where a hierarchy of firms have been established. Thus, when a lorry driver in Brambles thinks himself entitled to the same wage as a truck driver with ICI, EPEES is beginning to operate. Similarly, an electrician working with Toshiba would compare (for bargaining criteria) his wage with, say, what was paid to an electrician with Hitachi, rather than a small electrical firm around the corner. |

Source: Based on R.P. Dore’s Taking Japan Seriously.72

Comparisons and Adaptions

Earlier this Chapter observed that Japan fascinated Westerners in the 1940s and 1950s as an example of a country on the path to industrial development. Even as Japan formed enterprise unions and began to adapt to the requirements of a liberal, democratic society there were fears that free trade unionism would fail to take root and would instead sink into the swamp of Japanese cultural traditions.73 Nowadays as Japan strides along the road of ever increasing technological advancement and records impressive levels of real economic growth, the fascination with Japan has switched to that of a society which somehow has got its act together at least economically and in the way that large parts of its industry have been able to innovate, survive and prosper. This does not mean that all is for the best and that Japanese society is worth emulating. Australians are likely to think that their standard of life, filled as it is with sunshine, wide open spaces and a society marked by tolerance and diversity, is far more preferable than what might be experienced, for example, by the average Osakan or Tokyo resident. But that is not to say that there is nothing in Japan worth noticing and considering as potentially applicable to Australian circumstances.

In the field of industrial relations there are many things worth noticing about Japanese practices and worth pondering over. Four points come to mind.