Notes of a speech to the Institute of Management Consultants of Australia, 1 April 1991

Introduction

The Accord!

The Accord was originally negotiated between the then Federal opposition and the ACTU in March 1983 and it formed the basis for economic reform in Australia, once the Hawke Labor government was elected. For the first time in Australia’s history, traditional European concepts such as “corporatism” and “tripartitism” became central to the “economic jargon” of the period.

Inflation was at 11.5% in 1981/2 (a period of experimentation with free market IR policy) and economic growth was at -0.8%! And unemployment was at 10.4%.

What was in the original Accord?

- The Wages freeze was extended by 6 months so as to take pressure off wage inflation which had been evident in some sectors (e.g., the Amalgamated Metal Workers’ Union successfully pursued a 25% wages claim only 6 months prior … so much for the free market!)

- Wage increases were linked to the CPI

- A productivity based wages case was promised for “sometime in the future”.

- All this in the context of the “trilogy” of wages and prices restraint (hence the setting up of the Prices Surveillance Authority), industry reform (tripartite industry councils were set up to oversee this) and taxation reform (introduction of Capital Gains Tax etc.).

- Further, the “Social Wage” was to be enhanced by OHS laws, improved education, health (medicare) and social security systems. One of the key concerns of the Accord was to bring about an equitable redistribution of income among Australian workers.

- Strikes over wage claims were prohibited for the duration of the agreement by the “No Extra Claims Clause”, which ensured some semblance of industrial harmony.

- All changes to working conditions were to take place in a framework of consultation and co-operation between the parties that were involved.

- Job creation was pursued with a commitment to ensure that the economy grew by at least 500,000 jobs by 1986. The Commonwealth Employment Service (CES) was expanded. Retraining programmes were initiated.

1984

By 1984, the first signs of strain began, as the September NWC was deferred (with the agreement of the parties) because of the introduction of Medicare. There was a decline in the inflation rate and the unemployment rate, together with a pick-up of economic growth.

1985

October 1985 – Full CPI increase

April 1986 – 2% tax offset (introduction of taxation reform – also economic effects of devaluation)

1986

September 1986 – Further tax offset of 2%

Background economic circumstances which brought about need for award restructuring

– Slide in value of Australian dollar in early 1985 of almost 30% relative to other international currencies

– Collapse in terms of trade

– Foreign debt as % of GDP 1980 6.1% 1988 30.4% – The Banana Republic Syndrome

– Unexpectedly high CPI figure brought about by above

– All this brought about the perceived need for microeconomic reform, especially in the manufacturing sector

– Linked to environment of deregulation and reduced tariff protection. Note however, all this took place within context of the Accord.

1987

Award Restructuring

The “Two Tier System” in 1987 – The Beginning

Tier One $10 flat for all workers (except apprentices & juniors who got a % increase)

Tier Two 4% based on “Productivity Improvements”

Productivity and flexibility (at the workplace level) improvements were the focus of the 2nd tier. These included:

– Numeric flexibility (changing numbers of workers employed or introducing part time or casual workers)

– Time flexibility (more flexible arrangements for working time including overtime, shiftwork and starting and ending times)

– Wage flexibility (The ability of wages to adjust to changes in output, productivity and profit levels – again in individual enterprises

– Functional/Technical organisational flexibility (Job rotation, multiskilling, grouping of tasks, reduction of job demarcations)

– Procedural flexibility (development of tripartite mechanisms and means of worker/management consultation therefore facilitating a more flexible approach to dealing with changes in economic circumstances. One example of this is the widespread introduction of Electronic Funds Transfer for payment of wages … but there are many more.

1988

The 1988 National Wage Case – Award Restructuring Embraced

In the 1988 NWC the Commission shifted emphasis away from ad-hoc cost and productivity offsets typical under the “2nd tier” negotiations, and focused more on changes to the structure of the award and inherent prohibitions to improved productivity. The aim was to improve award structures so as to ensure that they were relevant to modern competitive requirements, as well as to provide workers with more varied, fulfilling and better paid jobs. This approach included the following courses of action:

– The introduction of a compulsory superannuation component into the wage fixation system of 3% (as a form of trade off for the “postponed productivity case” and the “delayed tax cuts” promised in the original Accord. Some sectors had received this benefit as early as 1986.

– The formal development of career paths for workers

– The creation of training opportunities for all workers (ranging from simple English on the job training to highly technical off the job courses)

– The integration of awards into a more simple, less complicated classification structure which will result in less union and job demarcation at the workplace.

1989

1989 Structural Efficiency Principle (as a result of the August 1988 NWC)

Two equal instalments of $10, $12.50 or $15 depending on skill levels. (Again, different arrangements for apprentices and juniors)

First tier based upon a “demonstrated commitment” to identify and seek to improve efficiency in various aspects of the relevant award.

The second tier was paid if the structure of awards was improved so as to allow career and pathing and training to have significants. This involved the creation of more structured classification systems, linked to systematic accredited training opportunities. In many cases, new entry levels had to be identified and created so as to recognise skills and qualifications gained in other areas of employment, if that training was relevant to the employment. In the past, these skills were often ignored! The concept of portability of training and qualifications is essential if multiskilling, broadbanding and career pathing is to be successful! Structural efficiency was designed to facilitate the practical realisation of award restructuring through the elimination of restrictive award provisions and the realisation of ongoing productivity improvements as a result.

Further provision was made for “supplementary payments” to be given so as to ensure that awards more closely reflect workplace payment practice – although this has not occurred in the NSW system.

The process of reviewing the Structural efficiency principle and expanding its effect has carried on throughout National Wage Cases since the original review in February 1989.

1990

1990 the Accord mark VI – Shattered

September 1990 – CPI based wage Increase (Later replaced by the 0.7% tax cut for all workers)

Further 12/week 6 months later.

Superannuation increase of 3% as of March 1991.

Productivity based claim of up to 4%

Ongoing commitment to broadband classifications, Create new job specifications, support training and retraining, Ongoing commitment to no extra claims.

Aggregate Wage target for 1990/91 = 7%.

The Practical Affect of Award Restructuring and the Structural Efficiency Principle (SEP)

There is no doubt that considerable productivity improvements have been achieved in certain areas as a result of the work of unions and employers careful and painstaking work in rationalising the classification system and the structure of Awards generally.

One notable example of this success can be seen in the Metal industry where in 5 years, an extremely complex system of over 140 classifications pertaining to various forms of training and experience has been rationalised into a basic 14 tier classification structure, each with a clear set of education and training requirements. This, over time, will ensure that workers are recognised for the skills they acquire,

– that these skills are portable (or bridging courses are readily available),

– that workers doing similar work (according to the skill levels, training levels and responsibility involved in the job) are remunerated accordingly,

– that logical career paths are readily available to workers and that these are not restrictive, that demarcations are both more understandable and are designed to encourage efficient and effective work practices.

One important result of the “Accord” and the practical implementation of Award Restructuring has been the development of mechanisms both at the industry level and the company level for consultation where decisions have had to be made.

Decisions such as which job fits into which classification; or which job can be broadbanded with another, etc.

The development of such consultative mechanisms (as required by the Award) results in a degree of commitment from all parties to the process. This is an important key to the success (or otherwise) of Award Restructuring. To develop a co-operative atmosphere where change is required is a massive advance from the reactionary and automatically hostile response that employers and unions have traditionally confronted each other with – when faced with changing conditions – or proposals for change in the past.

However…Not all groups of workers can have the principles of award restructuring applied as easily as the metal industry or the manufacturing sector generally. Many workers feel that this is simply a way of making workers jump through unnecessary hoops prior to achieving CPI based wage increases.

For example, the Australian Workers Union (AWU) have had considerable trouble with shearers! Very difficult to apply principles of career pathing, broadbanding and multiskilling there. Many members take the attitude that they are too old to undergo training, and do not feel that it is appropriate for their industry or occupation in any case.

Many public sector workers feel that they are engaging in a time consuming exercise in paper shuffling with little practical result other than having staff cuts enforced upon them with little workplace consultation taking place (occasionally unions are informed)!

The fruit and pastoral industries have also had considerable difficulty in giving practical effect to the broad aims of Award Restructuring.

Some criticism that the entire system has disadvantaged women in that they are concentrated in industries where award restructuring is “not so meaningful” such as in the small business and service industries (often un-unionised).

Further, up to 24% of the workforce have yet to receive the 2nd tier wage increase, let alone any subsequent decisions involving superannuation or productivity based wage increases as a result of Award Restructuring or SEP.

This final criticism is no doubt, in part, a factor which influenced the Commission’s decision not to accept the Accord Mark VI as negotiated between the union movement and the government. So many areas have not yet caught up with the first round of occupational superannuation that some suggest that it would be difficult to justify a further increase at this stage. Indeed, the IRC explicitly noted in their NWC decision yesterday, that they are well aware that many employers are not meeting their obligations regarding superannuation.

In my view however, the decision lacks vision in many respects.

– It prevents employers which do have considerable scope to improve productivity via SEP changes to a mere 2.5 %!

– It disadvantages the more poorly paid sectors of the workforce, many of whom do not work in occupations where SEP can be readily measured or applied (or where employers are hostile to such objectives);

– It effectively puts back the expansion of the occupation superannuation programme, despite its value in terms of investment potential and reduced long-term burden for government welfare.

– The Commission appears to be almost the only body which does not wish to move towards a more enterprised based focus!

The attitudes of workers and union members towards change and improving efficiency in production and provision of services, is entirely linked to their confidence in the system of wages fixation and its ability to deliver the original goals as set out in the Accord Mark I. In my view, the latest decision does little to progress that goal.

The decision undermines the confidence of workers in the institutions of wages fixation at just the time when in some influential sectors, they are embracing the ideals of improved efficiency achieved through structured consultation and co-operation.

It is true that the recent decision includes many of the elements which have led to improved workplace performance in the manufacturing sector (in particular). But without the confidence of the workers, this could all be lost!

Outline Of Classification Structure

| Classification | Classification Title | Training/ Education Requirement | Weight Of C10 Wage Rate |

| C1 | Professional Engineer Professional Scientist | Degree | N/A |

| C2(b) | Principle Technical Officer | Diploma or Formal Equivalent | 160% |

| C2(a) | Leading Technical Officer Principal Engineering Supervisor/Trainer/Co-ordinator | 5th year of Diploma or Formal Equivalent | 150% |

| C3 | Engineering Associate – Level II | Associate Diploma or Formal Equivalent | 145% |

| C4 | Engineering Associate – Level I | 3rd year of Associate Diploma or Formal Equivalent | 135% |

| C5 | Engineering Technician – Level V Advanced Engineering Trades person Level II | Advanced Certificate or Formal Equivalent | 130% |

| C6 | Engineering Technician – Level IV Advanced Engineering Trades person Level I | 1st year of Advanced Certificate | 125% |

| Classification | Classification Title | Training/ Education Requirement | Weight Of C10 Wage Rate |

| C7 | Engineering Technician Level III Engineering Tradesperson – Special Class Level II | Post Trade Certificate or Formal Equivalent | 115% |

| C8 | Engineering Technician – Level II Engineering Tradesperson – Special Class Level I | Completion of 66% of qualification for C7 | 110% |

| C9 | Engineering Technician – Level I Engineering Tradesperson – Level II | Completion of 33% of qualification for C7 | 105% |

| C10 | Engineering Trades person – Level I Production System Employee | Trades Certificate or Production/ Engineering Certificate III | 100% |

| C11 | Engineering/Production Employee – Level IV | “Production/ Engineering Certificate II” | 92.4% |

| C12 | Engineering/Production Employee – Level III | “Production/ Engineering Certificate I” | 87.4% |

| C13 | Engineering/Production Employee – Level II | In House Training | 82% |

| C14 | Engineering/Production Employee – Level I | Up to 38 hours induction training | 78% |

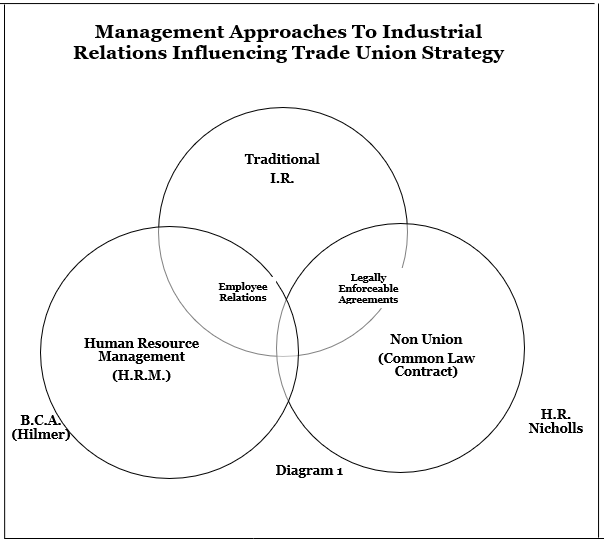

Management Approaches To Industrial Relations Influencing Trade Union Strategy

Postscript (2014)

These were notes I used in explaining the Accord processes up to the year 1991 and the associated, contemporary debates about the ‘system’, what was happening, the recent journey, arguments for change, as well as tensions along the rivet lines.