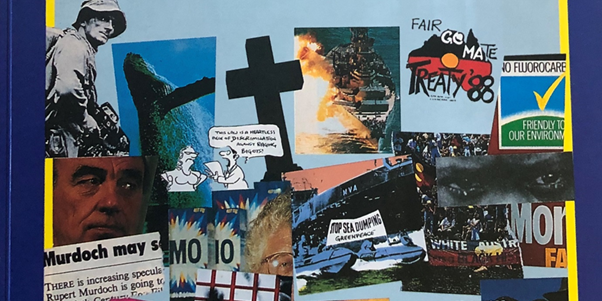

Essay published in Richard Giles, editor, For and Against. An Anthology of Public Issues in Australia, Brooks Waterloo, Milton [Queensland] and Gladesville [NSW], pp. 317-323.

Each generation discovers reasons to support, enliven, scorn, oppose or merely tolerate unionism. An amazing array of opinions exist about unions and their role in Australian life – ranging from the dream that unions exist to build a new Jerusalem to the notion that unions are old-fashioned and expensive hindrances to an efficient economy. I am unable to argue all of the points that are made about unionism in Australia. One short chapter is not enough space for that task. But questions will be asked and answered – and in the process, discussion will take place as to the contemporary activities of and dilemmas bothering the Australian union movement.

What are some of the key issues about unions in Australia? Let us consider eight controversial themes:

(1) Who belongs to unions?

(2) What will unions do for me?

(3) What have unions achieved?

(4) Shouldn’t strikes be illegal?

(5) Don’t unions stunt productivity improvements?

(6) Do unions have any vision for Australia?

(7) Unions have done good things in the past, but hasn’t time passed them by?

(8) Are unions democratic?

These questions are searchlights penetrating to the core of why unions exist, what they do, what they strive to achieve and what worries them about the future.

Unions cover virtually every occupation and industry. Your school teacher, the bank clerk and the nurse at the local hospital are likely to be union members. About 50 per cent of the Australian workforce are union members. CSIRO scientists, wharf labourers, shop assistants, metal workers, plumbers and engineers are examples of types of workers likely to be union members.

There are over 300 unions in Australia, although more and more are amalgamating or merging. The biggest thirty unions would have over 70 per cent of union members.

So practically anyone in employment can be a union member. For example, the stars in the ‘Neighbours’ television show, the journalists appearing on the television news and most Australian movie performers are union members. Indeed one famous Australian movie star, Paul Hogan, was for a short time – in the period he worked as a rigger on the Sydney Harbour Bridge – a union official with the Federated Ironworkers Association.

Unions are self-help cooperative societies. By joining a union, a person adds to the overall strength of the members, which is important for negotiating strength and the representative character of a union. What does this mean in practical terms? Well, a typical union will assist a member in the following ways:

1) Negotiate at an industry and/or workplace level for improved wages, career structure, and improved training of workers.

2) Negotiate at an industry and/or workplace level for better conditions, for example, decent amenities and improved health and safety standards.

3) Encourage the employer to be fair in work practices. Unions have historically acted to curtail discrimination in the hiring, promotion and dismissal processes. Defend members who are unreasonably treated by employers. This may include proceedings before an industrial tribunal.

4) Represent members’ views to management. Most unions recognise that workers are more than mere cogs in an industrial machine and that their opinions can improve productivity and unlock impediments to enterprise.

The ability of a union to deliver in these areas is significantly related to the support, including the joining of a union, by workers in an industry or workplace.

Without the industrial gains achieved over the years by unions, working life would be a miserable existence for many workers. For example, unions won the following benefits:

1) ‘Equal pay for equal work’ — this principle was accepted by the industrial tribunals in the late 1960s, but only after a sustained campaign by unions. Much still needs to be achieved in this area, in view of the discrimination which still exists.

2) Shorter hours: in 1856 building workers in Victoria won the right to an eight hour, six day week, making a 48 hour week. In the 1920s and 1930s unions won a 44 hour week. In the 1940s the 40 hour week was a major industrial claim and was achieved for nearly all workers by 1947. In the 1970s and 1980s hours were reduced further to 38 hours or 35 hours per week for most union members.

3) Wage increases are achieved by unions for their members. This usually requires industry or workplace negotiation and can involve expensive appearances before industrial tribunals. Wage increases are not gifts from employers – they have to be justified and won in the bargaining process.

4) Overtime rates and penalty rates to compensate for working long hours or inconvenient hours are basic entitlements in most industries.

5) Annual holidays are another significant union win, including annual leave loading (usually 17.5 per cent of normal wages). Think how different life would be working fifty-two weeks a year without a holiday break!

6) Sick leave – to allow workers who are ill to be compensated for short periods off work – is another union-achieved benefit taken for granted in today’s workplace.

7) The right to maternity leave is a major union gain achieved in the late 1970s before the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission.

8) Long service leave, superannuation coverage, fairer job hiring and employment practices are some of the other things that unions are proud to have achieved.

Like most conditions and entitlements, these achievements are only as permanent as society will allow. There are many in the community who believe that such gains should be ‘rolled back’. Therefore union members, as well as forging ahead with new claims, must also defend what is worth defending of recent gains, and those won by trade union pioneers.

Strikes are never pleasant experiences. For much of the last hundred years the industrial relations record in many Australian industries has been adversarial and brutish. For example, the mining, waterfront, pastoral and metal industries bear witness to ugly incidents, bitter strikes and sometimes bloodshed. Why? There are many and complex explanations about Australia’s industrial relations history, which can largely be traced in the reports of umpteen Royal Commissions and government inquiries held over a hundred years.

Economic hardships, coupled with an absence of tolerance and reasonableness, usually featured in many such clashes. Even if society has been vastly transformed, industrial action still persists. Whether this is because of a failure of the industrial relations system or the economy, or the fault of the parties, or a mix of those factors depends on how unions and industrial behaviour are regarded.

The right to engage in industrial action also entails a duty to take care that the issues and proposed activities are proportionate and reasonable. The following tests are useful guides for unionists in dispute: first, has every means to effect a settlement been tried?; second, would a strike be justifiable?; third, is the time opportune for a strike?; fourth, what are the possible sources of financial support?; fifth, what are the chances of winning?

Most unions try to avoid strikes like the plague – after all, workers pay a price for strike action by losing all of their wages for the period they are off work. So the issues leading to industrial action must be important and worth it. ‘Should strikes be illegal?’– Generals Jaruzelski and Pinochet, the dictators of Poland and Chile respectively, would certainly agree. However, besides being repugnant to civil liberties, banning strikes also shuts off industrial action and builds up resentments and tensions within society. A more intelligent approach to the issue of strikes and industrial action is to examine the causes of disputes, the way remedies can be found and the means of encouraging a positive industrial relations culture.

The oldest argument against unions is that they are against free trade and hindrances to an efficiently working economy. This argument asserts that because unions attempt to maximise the share of profits going to employees and to improve the wages and conditions of employees, successful union activities therefore divert company funds away from new investments and, consequently, improved productivity within an enterprise.

Such assertions are simple-minded, dogmatic and, moreover, ignore evidence against their conclusion. For example, even if it is true that unions can act to restrict productivity improvements, that is not the end of the affair. Unions interact with the company culture, the economic and social setting, the competence and intelligence of management. When the company philosophy is a form of dictatorship from above with little consultation with employees, when the wages are low and when times are tough, unions are bound to react to some of this. Possibly, the union members will respond to such a situation through frequent industrial disputation, low individual productivity and high labour turnover. Someone examining the results may conclude that the union is acting to restrict the company’s effective performance. But what a flimsy analysis would it be to leave it at that! Clearly the productivity of a workplace has a great deal to do with the overall managerial style and culture. More often than not improving productivity requires sensible cooperation between workers and their so-called superiors; between unions representing employees, and management.

Interestingly, in Australia many employers were startled in 1987 and onwards with the experience of negotiating with unions over restructuring awards, eliminating restrictive work and management practices, tapping employees’ suggestions for work reorganisation, formulating career paths and skill enhancement arrangements. In March 1987, the National Wage Bench of the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission introduced a new wages system which encouraged such industry and workplace bargaining. Particularly in the manufacturing industry, the unionised sectors of the workforce recorded impressive productivity improvements. Unions as organisations were able to effectively coordinate and present improvements to employers and win over workers to proposed changes.

Unions can aid productivity improvements by: encouraging the settlement of grievances thereby improving morale and reducing labour turnover (and the costs of recruitment and training); bargaining for changes in work and management practices leading to enhanced efficiencies; negotiating with employers to improve training and career structures within a firm, thereby adding to the productive potential of each employee; forcing management to pay more attention to labour discontent (this usually has a side effect of improving the quality of management); and ensuring that a much higher proportion of wages than would otherwise be the case is paid by way of superannuation, insurance and other forms of savings which are, in turn, invested in the economy.

Everyone now recognises that unions can – like other social organisations – decline and fail. Without an overall vision or sense of mission the appeal of unionism may diminish – particularly in today’s affluent society which only remotely resembles the society from which unions first emerged.

The spectre haunting the Australian union movement is that, by the turn of the century, the union movement may be much diminished in membership, appealing to declining sections of the workforce and, in sum, be no longer a major force in the economic and social life of Australia. Such a situation is a real prospect. In 1987, the Australian Council of Trade Unions published a report, Future Strategies for the Union Movement, which searchingly examined the strategies needed to extend the relevance of unionism. The report highlighted:

1) the low rates of unionism amongst younger workers;

2) the fact that, in the mid-1970s only 35 per cent of the private sector workforce was unionised (compared to 75 per cent in the public sector);

3) that many newer industries such as the computer, services and professional industries are barely touched by unions;

4) that some significant employer bodies, New Right pressure groups and the conservative parties are advocating a curtailment of union influence;

5) the generally poor image of unions as portrayed by the media and perceived by the public; and,

6) demands by union members for professional and innovative services by their unions.

The report recommended that unions should:

1) project a vision for a better Australia, including support for the right to achieve employment and training for all;

2) become more efficient by merging into twenty key industry groups, thereby pooling resources and enabling unions to provide better services to their members;

3) develop new services for members including, if possible, a union credit card scheme (available to all union members and providing discounted interest rates), discounted travel schemes (that is, cheap holidays for members), discounted legal services (organised through union-recommended law firms), death and disability cover, medical services and union sponsored credit schemes;

4) become more relevant to the working lives of their members at the workplace, promote greater worker participation and become intimately involved, with extensive workplace consultation, in the restructuring of awards and skills enhancement;

5) rediscover the art of recruitment – in new industries and poorly union-organised sectors of the workforce there is need to emphasise the responsible and service-related benefits of union membership;

6) act to extend superannuation coverage and win improvements in existing schemes, thereby extending the right to a reasonable retirement income. A number of industry schemes – including joint union and employer superannuation initiatives – were established to achieve that result.

Time will tell how successful will be this strategic response and vision for trade union changes.

The assertion that unions were once appropriate but are no longer relevant confuses several issues: the circumstances giving birth to unions in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have certainly changed. It is also true that the tasks facing unions are much different today.

Times have changed but that fact does not justify the obliteration of unionism. There are still plenty of reasons why unions should continue – most people are employed and differences will always emerge as to what are appropriate wage rates, career structures and working arrangements. As representative bodies, unions act to resolve such differences.

Unions do not exist in a Utopia – they spring up and flourish because, in an imperfect and pluralist world, unions are channels of communication, forums for grievances to be aired and settled, signposts of the civic culture.

Certainly, outdated methods of organising and rigid thinking about new problems and issues will cause unions to dwindle. That is why so much rests on each generation of union leaders and union members to effectively relate to society’s problems, listen to new members and educate, agitate, organise.

In one sense we get the unions we deserve. In Australia the key leadership positions of unions are elected by the membership. For example, the State secretary and the union executive positions are usually directly elected through a postal ballot of all of the members; this is required by the industrial laws of Australia and by most State governments.

So the members of a union have the decisive say in the leadership of their union. Every three or four years the leading union officials can be voted out of office – a certain result if he or she does not perform effectively.

Unfortunately, not everyone votes in union elections. Voting is not compulsory and because of apathy the average vote in union elections is 25 per cent (that is, 25 per cent of the members bother to vote). It is up to everyone to participate in their union – hence the phrase ‘we get the union we deserve’.

Electing the top officials of a union is not the only sign of union democracy (though it is a vital safeguard against arrogance and unrepresentative minority takeover). There is also the fact that union members select their representative (usually called the shop steward, union delegate or office representative) at the workplace.

The organised representation by unions of members’ grievances, claims and their ideas for changes to management practices are fundamental to any notion of democratic behaviour at the workplace.

All the theoretical arguments in favour of unions dissolve to insignificance if unions cannot justify in practical and significant ways their relevance to workers. The Australian workforce is changing – tugged in various directions by technological changes, higher educational standards and different demands of a sophisticated and affluent workforce. The traditional union constituency of low-paid, blue-collar workers, like the proverbial poor, may be always with us. Whereas in 1939 that constituency was a major component of the workforce, and of union membership, now it is a relatively small proportion. If the modern Australian union movement seems affluent, highly educated and sophisticated, it is because much of its membership is or aspires to that.

Unless Australian unions continue to broaden their appeal, extend the range of services they offer and more closely integrate into and shape the major economic and industrial issues, history may see the 1980s as the time when the forward march of industrial labour stopped. But the verdict on the 1980s is yet to come. Ironically, much depends on what will happen in the 1990s.

In a real sense, the achievements, failings, advances and struggles in the rest of the twentieth century will influence the judgment on contemporary times. Whether the union movement is capable of identifying and reversing adverse trends, creatively answering the criticism that ‘unionism has had its day’ through organisation, new services and intimate involvement in workplace changes depends on what is done now.

This article has tried to briefly rebut some of the mindless criticism sometimes advanced against unionism. Hopefully, the reader will acknowledge – despite all that may be said against – that unions are worth defending and worth joining.

Discussion Questions

1 Have trade unions exceeded their legitimate role in society – for example, by their actions in social and political issues?

2 Is compulsory unionism justified?

3 Are unions needed today?

4 Should trade unions be able to contribute funds to the Labor Party?

More Information

Reading

ACTU, Future Strategy for the Trade Union Movement, ACTU, Melbourne, 1987.

ACTU Youth Book. Labor Council, annual, any volume.

Australia Reconstructed, AGPS, Canberra, 1987.

Cole, Kathryn (editor). Power, Conflict and Control in Australian Trade Unions, Penguin, Ringwood, 1982.

Dabscheck, B. & Niland, J., Industrial Relations in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1981.

Davis, Ed., Democracy in Australian Trade Unions, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987.

Dugan, Michael, Trade Unions, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1981.

Freeman, Richard B. & Medoff, James L., What Do Unions Do?, Basic Books, NY, 1984.

MacFarlane, L.J., The Right to Strike, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1981.

Markey, Raymond, The Making of the Labour Party in New South Wales 1880-1900, University of NSW, 1987.

Martin, Ross, Trade Unions in Australia: Who Runs Them, Who Belongs – Their Politics, Their Power, revised edition, Pelican, Ringwood, 1980.

Nairn, Bede. Civilising Capitalism, ANU, Canberra, 1973.

Rawson, Don, Unions and Unionists in Australia, 2nd edition, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1986,

Turner, Ann (edition), Union Power – Jack Mundey Versus George Polites, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1975.

Your Rights at Work, Labor Council of NSW, Sydney, 1988.

Organisations

Institute of Public Affairs (IPA), Melbourne, Vic.

Labor Council of New South Wales.

Postscript (2015)

My entry in this excellent book on pro and con, for and against, was one of 33 topics. The intended audience were senior high school students. The editor, Richard Giles, was a teacher at Christian Brothers, Lewisham, in Sydney.

The Pro or For case arguing that unions were in need of urgent reform was written by Peter Costello.

Prior to writing my ‘reply’ for publication, however, I never saw Costello’s contribution. So I had to guess the arguments that might be assembled “For”. My contribution was the “Against” to the question ‘are unions in need of urgent reform?’.