Report completed 31 January 1996 by a panel chaired by Michael Easson and administered and supported by the Department of Finance. Republished here is the body of the Report minus most of the Appendices.

[original] Table of Contents

Foreword

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Overview and Main Findings

Background

The Terms of Reference

The Cash Management Problem

Principle Findings

Recommendations

Chapter 2: Statutory Authorities

Background Concerning Statutory Authorities

Methodology

Issues Concerning Statutory Authorities

Recommendations 1 and 2

The Cash Management Aspect of Funding Authorities

Recommendation 3

Appropriation and Commitment of Funds

Recommendations 4 and 5

The Payment Process

Recommendation 6

The Timing of Periodic Drawdowns

Cash Balances Currently Held

Recommendation 7

Adjust Appropriation Base Level

Recommendation 8

Government Policy Initiatives

Recommendation 9

Authorities that Distribute Payments on Behalf of the Commonwealth

Recommendation 10

Other Categories of Statutory Authorities

Recommendation 11

Conclusion

Chapter 3: Specific Purpose Payments

Background

Methodology

Categories of Specific Purpose Payments

Issues Concerning Specific Purpose Payments

Recommendations 12-13

Key Findings

Lack of Transparency

Recommendation 14

Payments Made in Advance or Retrospectively

Delays in Approval

Recommendations 15-17

Consolidation or Broad-Banding of Payments

Recommendation 18

Forward Planning

Receipts and Loan Payments

Recommendation 19

Matching Arrangements

Recommendation 20

Timing of Payments for New Policy Initiatives

Conclusion

Implementation

Recommendation 21

Chapter 4: Cash Management Functions of the Commonwealth

Introduction

The Treasury Function in Major Corporations

Treasury’s Role in Commonwealth Cash Management

Should the Commonwealth Establish a Treasury Corporation?

Corporate Treasury Functions in the Commonwealth

Recommendation 22

Appendices

Abbreviations

List of Consultations and Visits

Summary of Statutory Authorities’ Cash Balances

Summary and Comments on Statutory Authorities Examined

Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Australia Council

Australian National Training Authority

Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation

Australian Tourist Commission

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

Austrade

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

Employment Services Regulatory authority

Health Insurance Commission

National Gallery of Australia

National Museum of Australia

Suggested Pro-Forma for Draw Downs by Authorities

The Legal Position Concerning Appropriations

Specific Purpose Payments by the Commonwealth 1991-92 to 1995-96

The Specific Purpose Payment Situation in Each State

Summary and Comments on Major Specific Purpose Payments

National Highways

Education – Schools

Education – Higher Education

Health – Medicare Agreements

Home and Community Care

Housing

Local Government

Commonwealth/State Program: Building Better Cities

Suggested Pro-Forma for Specific Purpose Payment Draw Downs

Aggregation of Account Balances

Is There a Case for a Federal Central Borrowing Authority?

Foreword

This Report represents the views of Task Force Members based on our analysis of the issues and the factual information examined during our deliberations.

As each of the seconded members of the Task Force (Mr David Knapp, Dr Elizabeth Casling, Mr Eddy Owen, Mr Glyn Tomlinson and Mr Ross Allamby) have had to perform their normal duties in addition to work on the Task Force, this has meant that each of them has devoted significant “out of hours” time to fully contribute to the enormous tasks associated with the review of cash management issues in the Commonwealth.

I am very grateful for their diligence, patience and dedication to the tasks at hand.

Mr Dean Wallace and Mr Phil Bowen in the Department of Finance also provided helpful assistance at various points of the Task Force’s enquiries. Officers of the Reserve Bank of Australia were also particularly helpful in making suggestions.

This Report was developed in a short time frame. The Task Force met for the first time late in July 1995 and prepared an issues paper for circulation in August. As the areas covered were vast, this means that priorities had to be selected. Much ground was covered, much more quickly passed over.

Informality was encouraged. Apart from a few formal letters no submissions were received – or encouraged by the Task Force. Much information was received in an informal, off-the-record basis. For the most part, the Task Force members went out to find for themselves the facts. An intensive array of meetings (highlighted in the attachments) was organised.

This was necessary because of the short time available to prepare a Report and the need to unearth the factual story quickly. This was not so much a search for “buried bodies” but a search for “buried analysis”; the formal, submission process sometimes obliterates what is useful to know.

Hence, this Report reflects and sometimes heavily relies on what others have told us. We were grateful for the input from many sources; the firms BZW and Bain and Company provided some observations on parts of this draft.

However, in the final result, in the development of our analysis, formulation of our views and the selection of information, it is the Task Force that is responsible for what follows.

Michael Easson, Chairman, 31 January 1996

Executive Summary

Statutory Authorities examined by the Task Force had cash balances in total of more than $700m. A large part of this is considered to be in excess of need.

There is a cost to the Commonwealth in allowing payments to be made to Authoritiesin advance of their need for cash. Ministers and Departments should exercise a reasonable level of control over their draw-downs to ensure that they do not accumulate surplus cash.

Incentives should be developed to discourage Authorities from drawing surplus cash from the Budget.

The government should approve levels of expenditure by Authorities for current and future years, but not provide cash in advance of need. These arrangements could be included in resource agreements approved by the appropriate Ministers.

Appropriations to Statutory Authorities should make clear that the full amount need not be paid during the Budget year if it is not required for expenditure.

The government should require Authorities to reduce their cash balances where they are considered excessive. This can be done by restricting payments from the Budget until the cash balances have been run down to acceptable levels.

The States and Territories held aggregate cash balances of at least $200m in relation to Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs), as at 30 June 1995. As several States and Territories were unable to provide this information, it seems likely that this figure could be much higher.

There is a serious lack of transparency in relation to SPPs, which made it difficult to track Commonwealth payments. This should be addressed as a matter of priority.

Payment arrangements for SPPs vary. Cash management concerns arise where payments are made in advance of need.

SPPs should be based on rolling programs that would give a degree of certainty to the States, for planning purposes, but cash should be provided only on the basis of need.

Funding for SPPs should not be provided in advance of need. Where excessive cash balances are held in relation to SPPs, they should be run down by restricting payments until they have reached acceptable levels.

Appropriations for SPPs should be worded so that the full amount need not be paid during the Budget year if it is not required for expenditure.

The government should consider establishing an Office of Cash Management to oversight these and other efficiency considerations in the use of cash.

A Task Force should be established to implement the recommendations of this Report. It is considered that savings of the order of $400m could be achieved in the 1996-97 Budget on a one-off basis, together with ongoing Public Debt Interest Savings of around $30m.

The detailed recommendations of the Task Force are listed at pages 6 to 9 of this Report.

Chapter 1. Overview and Main Findings

Background

The Task Force on Payments to Statutory Authorities and Specific Purpose Payments to the States was established after a Cabinet decision in the context of the 1995-96 Federal Budget. It was estimated by the Department of Finance that one-off savings of $50 million and on-going savings of $5 million might be achieved through better cash management of payments to Commonwealth Statutory Authorities and the funding of Special Purpose Payments (SPPs) to the States.

This insight was an estimate of possible efficiencies that might be obtained from better cash management, including responses to some of the criticisms of the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO).

For example, in the Auditor General’s Efficiency Audit Report No. 10 1994-95 on Cash Management in Commonwealth Government Departments, the comment is made:

3.20 The ANAO believes that an understanding of the [cash] flows is essential. There is a need to be aware of the revenue receipting patterns so that when program proposals are being reviewed, as per the Department of Finance’s role, then if regular payment dates cannot be set as late as possible (consistent with program objectives) they can at least be delayed to coincide with revenue receipting dates. This would be preferable to selecting an earlier payment date on arbitrary grounds, such as the first of the month.

The coinciding of payments with revenue peaks is just one area where improvements could be organised.

The Auditor-General’s Audit Report No. 6 1993-94, being An Audit Commentary on Aspects of Commonwealth-State Agreements, also contained suggestions about improvements relating to cash management.

Cabinet responded to the Expenditure Review Committee’s recommendation to follow up on the Department of Finance proposals by establishing a Task Force on Commonwealth Payments to Statutory Authorities and by way of Specific Purpose Payments to the States.

This Task Force commenced its activities in late July 1995 with a report required by 31 December 1995. Mr Michael Easson was appointed by the Minister of Finance, Mr Kim Beazley, as the Chairman of the Task Force. Other members were Mr David Knapp (Department of Finance); Dr Elizabeth Casling (Department of Transport); Mr Eddy Owen (Department of Veterans’ Affairs); Mr Glyn Tomlinson (Department of Employment, Education & Training) and Mr Ross Allamby (Department of Finance), the Secretary to the Task Force.

Following the issue of a draft Report to the Minister in mid-December, the Minister extended the time for a final report to the end of January 1996.

The Terms of Reference

The government determined the following Terms of Reference:

The Task Force should examine the Commonwealth’s current arrangements for making payments to Statutory Authorities and to the States by way of Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs), to determine whether the arrangements represent sound cash management and a cost effective means of achieving program outcomes.

The Task Force should give particular attention to areas it considers to have the greatest potential for savings to the Budget, but should examine a sufficiently representative cross-section of Authorities and SPPs to be able to recommend a policy framework for managing such payments.

In undertaking this inquiry, the Task Force should examine the following matters and any others that it sees as relevant to achieving the above objectives:

- current procedures for making payments, with special attention to timing;

- the level of cash and financial assets held by Statutory Authorities and recipients of SPPs;

- present arrangements, if any, for identifying the periodic cash requirements of Statutory Authorities and SPPs;

- matching or other financial obligations of recipients and whether these are being met in a timely way under current payment arrangements;

- scope for one-off Budget savings in 1996-97, to allow for run down of any accumulated excess balances of cash and financial assets currently held by recipients:

- including the replacement of accumulated cash and financial assets with an undertaking by the government to provide cash (to agreed limits) from appropriations to meet accruing liabilities and provide for asset replacements, as they fall due;

- scope for ongoing Public Debt Interest savings by making periodic payments to recipients only on the basis of certified need\ as supported by estimates of cash on hand, receipts and outlays for each period;

- whether recipients would be adversely affected by any recommended changes in payment procedures;

- the impact of any recommended changes on program delivery.

The Task Force should consult direct with Authorities and state government bodies as appropriate. If necessary it should ask the Prime Minister to formally request state governments to cooperate by allowing reasonable access to relevant official sand documentation, to assist the Task Force in its enquiries.

The Task Force should report to the Minister for Finance by 31 December 1995.

The Cash Management Problem

The timing of receipts and payments is the fundamental issue in cash management, due to the amount of interest that is associated with these cash flows. Receipts collected early can earn extra interest for the recipient, while payments made too early reduce the interest earned, or add to the interest that must be paid by the payer if the funds are raised by borrowing. It is therefore sound cash management for any organisation to collect receipts as early as possible and make payments as late as possible.

Consequently, it is in the Commonwealth’s financial interests to collect its receipts by the due date and make payments as late as possible, subject to meeting its contractual obligations and normal business standards. This will maintain the Commonwealth’s cash balances at the maximum level in the short term and reduce the Commonwealth’s borrowing requirements in the medium and longer term. The end result is that the Commonwealth’s net Public Debt Interest (PDI) is minimised.

It is important to the Commonwealth, for cash management reasons, that the payments referred to in the Terms of Reference are not made significantly in advance of need of the recipients. These types of payments are usually made by installments, so that they are spread over the year rather than paid as a single lump sum. The Commonwealth’s payments to Statutory Authorities and the States via Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs) run into billions of dollars each year.

The Commonwealth’s financial operations are transacted through receipts to and payments from the Commonwealth Public Account (CPA), and any deficiency of funds must be met by borrowings.

There is scope to significantly reduce the Public Debt Interest (PDI) cost of the Commonwealth’s borrowings, by better managing the timing of these payments.

The Commonwealth is typically a net borrower throughout the year. Its PDI bill can be minimised by making payments as late as possible consistent with effective program delivery objectives, thereby deferring the need to raise funds by borrowing. The legitimate activities of the Authorities and States should not be constrained by withholding monies appropriated by Parliament for payment to them. However, the timing of the payments should be such that the recipients receive the monies as they need them and not significantly before this. If payments are made before they are needed for genuine expenditure purposes, the States or Authorities are able to accumulate surplus funds at a significant cost to the Commonwealth. This reflects the fact that the Commonwealth will have had to borrow funds through the money markets for periods longer than would have been necessary had proper cash management practices been followed. Hence a “just-in-time” Cash Management approach is appropriate.

Over a longer period, consistently making payments earlier than is necessary to achieve program outcomes will also allow the recipients to accumulate surplus cash balances. It would clearly be anomalous for the Commonwealth, which itself has accumulated nearly $100b in net debt and finds it necessary to borrow approximately $1 b each week through the Treasury Note tender, to be consistently making payments early, thereby enabling the recipient to build up an interest free pool of funds which it can invest or leave in a bank account to earn interest.

In summary, the Commonwealth can achieve PDI savings by making payments to its Authorities and to the States, via SPPs, on a strict cash requirement (“just in time”) basis.

Principal Findings

Large balances of surplus cash, running into hundreds of millions of dollars, were held by the Statutory Authorities examined and the recipients of SPPs. There was more evidence to support this in the case of Authorities, because they provide information about their cash and investments in their published financial statements. There was generally a lack of transparency in the case of the SPPs, as most States do not provide published information concerning unspent balances of Commonwealth cash. Some State Treasuries indicated to the Task Force that this information was not available. However, there was information from several States and Territories which indicated that they held very large balances of unspent Commonwealth cash at year end, in recent years.

While it is not possible to be precise because of the large number of Authorities and SPPs and the lack of reliable, current information about SPPs, the Task Force concluded that cash balances, in excess of a reasonable working balance, held by the thirteen Statutory Authorities which were examined in detail, exceeded $700m at the end of June 1995 .

Overall, cash balances held by all Commonwealth Statutory Authorities, as recorded in their annual reports for 1994-95, exceeded $3 billion (see Appendix 3). However, this amount includes over $1 billion held by marketing bodies and industry research corporations. As such, it includes monies that were sourced from business operations and industry levies and it would therefore be incorrect to conclude that these cash balances represent monies sourced from the Budget.

Evidence available to the Task Force, in the form of published annual reports and data provided by some States indicated that the States as a group held significant unspent balances amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars, in relation to SPPs (see Appendix 8).

Although much is made of the idea of “best practice cash management”, this can be no more than a hollow phrase if a number of important changes to the culture, practices and activities of Departments and Authorities do not take place. Good cash management should be a feature of financial controls and the operating environment. The achievement of improvements in cash management requires a fundamental reassessment of the relationship between government funding and program outcomes; between the portfolio Departments and the Authorities or States that are charged with — and desirably contracted to — delivering those outcomes. The timing of funding must be closely linked to the delivery of program services.

It is apparent that the large balances in the hands of recipients were the result of Commonwealth payments being made well in advance of need – i.e., expenditure by the recipient — and of service delivery. In many cases, payments were made to Statutory Authorities throughout the year without any real attempt to monitor their spending patterns or the level of cash on hand. The practice in the case of Authorities and some SPPs was to pay, by the end of the financial year, the full annual appropriation or allocation regardless of whether this amount was likely to be spent during the year.

The end result is that the Authorities and States were able to accumulate cash balances that far exceeded their foreseeable needs for expenditure on core activities, thus giving them a pool of funds that they could invest or place in a bank account. The Commonwealth, which is a net borrower, bore the interest cost of raising these surplus funds while many Authorities and States reaped the benefit in the form of bank interest or investment earnings.

In many cases, the Departments responsible for administering these payments and the supply areas in the Department of Finance have not given a sufficiently high priority to efficient cash management practices. They have not sought to improve the transparency of accounting for SPPs to enable the Commonwealth to track the use of SPP monies. There has been insufficient examination of the balance sheets and other financial statements of Authorities to determine whether the level of retained funding is appropriate.

If the recommendations in this Report are adopted, one-off Budget savings of around $400m and recurrent PDI savings of $30m should be achieved from the Statutory Authorities that were examined. Additional one-off savings may be achievable from other Authorities that were not examined, together with unquantified savings from better cash management of SPPs.

To achieve the savings identified for SPPs it will be necessary to seek the co-operation of the States. There would be benefits to the States in the proposed arrangements in that there would be simplification of administration, consistency and greater certainty in relation to the support they receive via SPPs.

Recommendations

The Government should give consideration to the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1

The general principle governing the funding of Statutory Authorities which operate on their own bank accounts should be that payments to them are sufficient to meet their immediate cash needs and that they should not accumulate surplus balances of cash or financial assets as a result of early payment of Commonwealth monies.

Recommendation 2

Periodic payments to Statutory Authorities should be made on the basis of their immediate cash needs and the timing of such payments should therefore be carefully considered. There would be cash management advantages if they could be timed to coincide with Commonwealth revenue peaks each month and it is recommended that this be the norm.

Recommendation 3

In establishing Statutory Authorities, the Commonwealth should carefully consider whether there is a need for them to operate on a separate bank account, given the cash management costs of allowing cash balances to be held outside the Commonwealth’s aggregate balances with the Reserve Bank of Australia. Clear criteria need to be established. There should also be a review of those Authorities which currently have separate bank accounts to ascertain whether some could operate on the Commonwealth Public Account without detriment to their operations and need for independence.

Recommendation 4

The government should introduce a system of forward expenditure approval, which may take the form of ministerially approved resource agreements, for all Budget funded Authorities. The Budget papers should comprehend these agreements.

It should be possible for recipients to carry forward expenditure commitments into future years, thus avoiding the need to draw down cash in respect of those commitments until required.

Recommendation 5

The legislation providing for payments to Authorities and the States via SPPs should make clear that payments from appropriations will be made only to meet cash needs and that the appropriations need not be fully paid to Authorities or the States by the end of the year if the full amount of cash will not be required in that year. (Note: “cash needs” includes a reasonable level of working balance).

Recommendation 6

As an interim measure, each periodic payment to Authorities should be based on a cash flow statement to be prepared by the Authority taking into account cash on hand and forecast receipts and expenditure for the relevant period. In the longer term, the government should consider introducing incentives to discourage Authorities from drawing down payments from the Budget in advance of need.

Recommendation 7

Where Authorities are considered to have balances of cash and financial assets sourced from the Budget or Budget-funded activities that exceed their immediate requirements, they should not receive further monies from the Budget until those balances have been run down to an agreed level.

In some instances it may be appropriate to require the Authorities to run down their cash balances, but to allow them to draw an equivalent amount from the Budget in future years, when the cash is actually required for expenditure purposes.

Recommendation 8

Where there has been a history of significant under-spending by an Authority, there should be a review of the base level of the appropriation.

Recommendation 9

When the government announces policy initiatives that involve providing for additional levels of activity by Authorities or the States, the cash to support those initiatives should not be paid in advance of need for expenditure.

Recommendation 10

The benefit or payment component of the appropriation, currently made to those Authorities that disburse payments to final recipients should be retained by the Commonwealth, until the payment is actually made to the final recipient.

Recommendation 11

A further review should be conducted of the funding arrangements of those GBEs, marketing bodies and industry research corporations that receive monies from the Budget.

Recommendation 12

All new SPP Agreements should incorporate best practice cash management principles. Such principles include that, wherever feasible, payment schedules should coincide with monthly revenue peaks by the Commonwealth.

Recommendation 13

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) should finalise a Protocol covering the cash management of SPPs to the States.

Recommendation 14

The States and Territories should be required to account for Commonwealth monies throughout the year, and report to the Commonwealth all receipts, expenditure and unspent balances of SPP monies throughout the year and as at year-end.

Recommendation 15

A multi-year, rolling program, including program outcomes and indicative annual funding levels be agreed between the Commonwealth and States in respect of each SPP, in the context of the annual Budget. This would provide each State with an approved level of expenditure for the current and future years for each SPP, as opposed to the provision of cash for future expenditure in the Budget year. Cash would be provided on the basis of need. Annual appropriations should then be based on estimated cash needs within each year.

Recommendation 16

If the approved level of expenditure for an SPP is not utilised in full in a year, then the balance of the expenditure approval should be carried forward to future years, without detriment to the next year’s appropriation. If necessary, a State could apply to bring forward approved expenditure from a future year, but this would be a matter for consideration by the government at that time.

Recommendation 17

Funding should not be provided to a State until it is required; payments should be based on a full acquittal of previous cash receipts and forecast cash requirements.

Where the States disburse Commonwealth monies to final recipients, the Agreements should specify that the States are responsible for sound cash management practices in relation to those monies and that the monies will not be paid to recipients significantly in advance of need. The States should be required to certify that this practice has been implemented in their periodical reporting to the Commonwealth.

Recommendation 18

All SPPs “to” the States might be aggregated into a single periodic payment to each State government should that be mutually agreed. Alternatively, SPPs for each Portfolio should be aggregated, so that efficiencies in cash management and administration are achieved.

Recommendation 19

Where receipts or repayments result from activity supported by SPPs, the Agreements covering those SPPs should specify the ownership of the monies, whether they should be offset against future cash requirements and the accounting and monitoring arrangements in relation to those monies.

Recommendation 20

Where relevant, the Agreements covering SPPs should specifically address the matching contributions by the States and Territories including the timing and monitoring of those contributions.

Recommendation 21

A Task Force representing appropriate policy and administrative areas of the Commonwealth be appointed to implement the recommendations of this report, in consultation with the Commonwealth’s Statutory Authorities, the States and Territories.

Recommendation 22

The government give consideration to the establishment of an Office of Cash Management in the light of the issues raised in this Report.

Chapter 2. Statutory Authorities

Background Concerning Statutory Authorities

The government supports the funding of over 100 Commonwealth Statutory Authorities which cover a wide range of activities including transport and communications, industrial and scientific research, the arts, aboriginal affairs, sport, health, education and justice. The funding arrangements are varied. Some details concerning the cash position of certain Authorities are provided in Appendix 3.

The functions and powers of Statutory Authorities are determined by the enabling legislation under which they are established. In most cases the legislation specifies the financial arrangements of the Authority, which may include provision for the Authority to open and operate its own bank account. Where this is the case, monies appropriated to the Authority by the Parliament are paid to the Authority, usually by installments, and deposited to the Authority’s bank account. Such Authorities may also have limited powers to invest their monies and to borrow. Authorities which operate their own bank accounts in this way do not operate on the Commonwealth Public Account (CPA), which is the Commonwealth’s own central repository of funds, and their final expenditure and receipts are not recorded in the Commonwealth’s financial systems, except for the funding advanced to them. Neither are they subject to the main financial provisions of the Audit Act 1901 or subsidiary legislation such as the Finance Regulations or Finance Directions.

Many Authorities have wide statutory powers, which could be interpreted as giving them authority to participate in activities outside their core functions. For instance, the enabling legislation often includes, in the list of powers of an Authority, the power to do all things necessary or convenient to be done in connection with the performance of its functions (or words to that effect). This can give Authorities considerable flexibility in the use of their finances for investment and acquisition of property and assets.

Different categories of Statutory Authorities face different financial situations and there may be a case for considering the circumstances of different groups, such as:

- Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) which normally do not draw funds from the Budget (but may pay dividends to the Budget based on profits generated) are outside the Terms of Reference;

- Statutory Marketing Authorities (SMAs) and industry research bodies which draw all or a major proportion of their funds from levies upon the (primary) industry concerned (in some cases the Budget also contributes funds on an agreed basis, say, 50:50) — only those that draw on the Budget fall within the Terms of Reference;

- Authorities that operate on a quasi-commercial basis but draw primarily on the Budget for their funds — ABC, SBS, CSIRO, ANSTO; a major issue with these bodies is to consider a rationale for budgetary cash flows vis a vis “commercial business” cash flows;

- Regulatory, advisory, etc., bodies more closely related to core government activity and which are virtually wholly Budget-dependent for their funding;

- Bodies to which the Budget provides funds on a basis somewhat similar to a general purpose payment to a State/Territory.

Many Statutory Authorities that draw funds from the Budget have a provision in their enabling Acts along the lines: “Amounts appropriated by the Parliament for the purpose of the body shall be paid at such times and in such amounts as the Minister for Finance determines”.

This means that some control can be exercised over the flow of payments from a Parliamentary appropriation to an Authority, subject to legal advice to the effect that any amount appropriated for a financial year must be paid over in full by the end of that year, (see Appendix 6 for further discussion of the legal position).

Thus, the cash management task includes consideration of the amount to be appropriated each year, as well as the Minister’s power to allocate payments during the year.

Methodology

The Task Force examined the cash management of payments to Statutory Authorities operating on their own bank accounts, as opposed to Authorities which operate on the Commonwealth Public Account.

The annual reports and financial statements of a number of Authorities were examined and consultations subsequently held with administering departments, supply divisions of the Department of Finance and a number of the Authorities themselves. The cash draw-down schedules for those Authorities were examined and a set of fairly standard questions was put to them, modified to meet the circumstances of each one. Through this procedure, the Task Force sought to identify the payment processes followed in respect of each Authority under investigation, whether payments were being made in a timely manner on the basis of the Authority’s need for cash to meet its expenditure requirements, and whether the Authority had accumulated cash in excess of those requirements. Appendix 4 provides detailed information on the Authorities examined, and Table 1 indicates their reported balances of cash and financial assets as at 30 June 1995.

Table 1: Statutory Authorities Examined by the Task Force

| Organisation | Appropriations 1995 – 96 $m | Cash and Investments 30 June 1995 $m |

| Austrade | 401 | 195 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission | 894 | 84 |

| Australian National Training Authority | 925 | 35 |

| Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation | 423 | 146 |

| Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation | 66 | 25 |

| Health Insurance Commission (est.) | 8,000 | 151 |

| Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) | 622 | 29 |

| Special Broadcasting Service | 83 | 3 |

| Australia Council | 73 | 7 |

| Employment Services Regulatory Authority | 45 | 4 |

| National Museum of Australia | 6 | 3 |

| Australian National Gallery | 24 | 5 |

| Australian Tourist Commission | 80 | 12 |

| TOTAL: | 11,642 | 699 |

Issues Concerning Statutory Authorities

In examining the group of Authorities, the Task Force considered the following key issues:

DO AUTHORITIES PROVIDE A SCHEDULE OF FORECAST CASH REQUIREMENTS?

Many Authorities provide a schedule of cash requirements, mainly pro rata with adjustments for any lumpy payments. There appears to be scant monitoring or review of these schedules during the year, as payments are simply made on the basis of the originally agreed schedule. Authorities generally draw down funds for capital expenditure in equal instalments, without providing any forecast of when these payments will fall due, implying that they accumulate cash to meet these costs as they arise.

COULD DRAW-DOWNS BE MORE FREQUENT?

For large Authorities which currently receive monthly or quarterly instalments in advance of need, it appears to be feasible to provide fortnightly instalments which would result in deferring the borrowing requirement until a time closer to need, thus reducing Public Debt Interest. For example, where an Authority receives some of its program funding quarterly in advance, this should probably be rescheduled to provide it fortnightly on the basis of need. (An examination of each of the major Authorities occurs at Appendix 4).

DO DRAW-DOWN SCHEDULES TAKE ACCOUNT OF FUNDS ON HAND?

No. Authorities which have been examined have not been required to spend cash balances before drawing down their next instalment, nor have instalments been reduced in any way to allow for cash on hand.

COULD DRAW-DOWNS TAKE PLACE TO COINCIDE WITH COMMONWEALTH REVENUE PEAKS?

This would help to match the pattern of the Commonwealth’s expenditure with revenue – i.e., with taxation receipts which have peaks around the 1st, 8th and 22nd. It would be consistent with recommendations by the ANAO that Departments should match expenditure and revenue patterns to reduce Commonwealth borrowing requirements. If necessary, the first payment of the year in which the change was introduced could be adjusted to ensure that the effect of the change was neutral for Authorities, where an Authority’s working balance was insufficient to meet wage and salary and other recurrent commitments in the adjustment period.

SHOULD AUTHORITIES SET ASIDE CASH AGAINST SPECIFIC COMMITMENTS?

Some Authorities have earmarked accumulated cash for specific commitments, even holding such cash in separate bank accounts for subsequent expenditure on each major commitment or activity. This would be unnecessary, if those Authorities could be certain that cash would be available as required to meet maturing accruals, especially where commitments extend into future years. A firm commitment by the government to provide the cash as it is required to meet maturing accruals, within approved expenditure limits, would give this certainty. It may be necessary to provide the commitment in some formal document such as a resource agreement between the responsible Minister and the Authority.

HOW CAN AUTHORITIES PROVIDE FOR CAPITAL REPLACEMENT AND OTHER MATURING LIABILITIES?

Instead of drawing down cash in advance of need, Authorities should draw down funds as required for expenditure. Where large outlays are necessary, e.g., to replace major capital assets, the cost of which could not currently be met from a single year’s appropriation, Authorities could provide a forecast of such outlays based on agreed asset replacement plans and seek a formal undertaking by the government, such as a ministerial resource agreement, to provide funds when required. This would result in deferral of the draw-down until the funds are actually required to pay contractors, etc. Thus, while the recurrent provision may remain fairly constant over the years, the provision for capital expenditure may vary from year to year according to an approved forecast of capital expenditure, with funds only to be drawn down as required to meet payments.

DO AUTHORITIES HAVE SEPARATE BANK ACCOUNTS FOR VARIOUS PROGRAMS/ACTIVITIES?

Some Authorities hold funds for various programs or activities in separate bank accounts. This can have the disadvantage that they need a “buffer” of cash for each such activity. If they operated all programs and activities from a single bank account, they would only need a single “buffer” and hence could operate on a lower cash balance.

DO THEY HAVE GROUP SET-OFF ARRANGEMENTS FOR BANK ACCOUNTS/OVERDRAFTS?

As an alternative to the previous comment, Authorities could operate on a group set-off arrangement with their banker (many of the private banks and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) are willing to provide such an arrangement for large clients). This allows the client to operate a number of accounts as if they were one. This would enable Authorities to operate on a lower working balance than if each account was treated separately, because the balance of each account need not hold such a high buffer. It is not known whether many Authorities have availed themselves of this arrangement.

WHAT INTEREST RATE DO AUTHORITIES RECEIVE ON THEIR CASH?

Those Authorities which have provided this information generally receive lower interest rates than that paid by the Commonwealth on its borrowings, so from a whole-of-government perspective there is an actual loss on cash balances. The significance of this is discussed later in this Report.

COULD BETTER ACCOUNTING SYSTEMS ENABLE THEM TO MANAGE WITH LESS CASH?

If there was an incentive for the Authorities to operate on a lower cash balance (or disincentive to maintain large cash balances), they may wish to upgrade their accounting systems to forecast future cash requirements and hence operate on lower “buffers”. At present many are practising a form of “jam jar accounting” by setting aside cash for each future payment, instead of drawing cash as it is required.

[The Department of Finance has evaluated many commercial accounting packages (see Towards Better Financial Management, Department of Finance, Canberra, 1995) and can provide advice to Authorities on systems that would meet their needs. An appropriate FMIS would provide information on cash, accruals and commitments.]

CAN AUTHORITIES SEEK AN EMERGENCY DRAW-DOWN?

Authorities would also be encouraged to operate on lower cash balances if there were more flexibility in the draw-down procedure — i.e., if Authorities are genuinely short of funds in the middle of a draw-down period they can access a supplementary instalment at short (e.g., 48 hour) notice. Departmental systems can provide for this.

SHOULD AUTHORITIES PAY SUPPLIERS EARLY WHEN A DISCOUNT IS OFFERED?

Many Authorities seek a large payment as their first instalment for the year so that they can pay large accounts to Telstra, Comcare, etc., in advance and obtain a discount. The discount may be less than the cost to the Commonwealth of borrowing the funds. As the discount represents a windfall gain to the Authorities at the expense of the Commonwealth in those instances, such large initial draw-downs should not be provided. In particular, Authorities should not be able to draw such large initial payments if they are carrying forward significant levels of cash. Draw-downs could be provided in advance where the Authority met the additional, nominal borrowing cost.

SHOULD REVENUE BE TREATED AS “SEPARATE CASH”?

Some Authorities have represented revenue earned from Budget-funded activities — e.g., licence fees, gate money – as non-Budget money which should be excluded from consideration of appropriation and draw-down levels. While there may be a case for treating revenue from privately-funded activities as “separate” for these purposes, revenue from Budget-funded activities should logically be treated as being sourced indirectly from the Budget. Accordingly, it should be taken into account in determining the annual cash needs of Authorities and should be applied by the Authorities to their Budget-funded activities.

SHOULD AUTHORITIES BE ABLE TO CARRY FORWARD CASH?

Some Authorities have referred to arrangements with the Department of Finance, which allow them to carry forward cash balances from one year to the next as part of their resource agreement with that Department. They are legally entitled to any monies that have been appropriated to them within the Budget year, and once they have received those monies they may spend them or carry them forward as unspent cash or investments. However, the Commonwealth should take steps to limit the amount of cash that Authorities hold at any time by controlling the timing of draw-downs.

SHOULD AUTHORITIES WHICH HAVE EXPOSURE TO FOREIGN EXCHANGE RISK BE ABLE TO DRAW DOWN EARLIER THAN OTHER AUTHORITIES?

The Australian Tourist Commission (ATC) has been able to receive its appropriation in two six-monthly instalments on the basis that it must enter into forward contracts to hedge against its foreign exchange exposure. Advice from the Reserve Bank indicates that it is possible to hedge exchange rate risk without making advance payments – forward contracts are settled at a pre-determined exchange rate at the time foreign currency is received. The rationale for large draw-downs in advance is not warranted.

SHOULD AUTHORITIES PAY INTEREST TO THE COMMONWEALTH FOR CASH RECEIVED IN ADVANCE OF EXPENDITURE?

The ATC and Health Insurance Commission pay interest to the Commonwealth for cash received in advance of need. There is a case for this principle to be extended to other Authorities.

SHOULD THE COMMONWEALTH PAY INTEREST TO AUTHORITIES ON CASH THAT THEY “BANK” WITH THE COMMONWEALTH?

It has been suggested by some Authorities that they could pay back surplus cash to the Commonwealth and receive interest from the Commonwealth equivalent to the bank interest forgone. There seems to be no justification for the Commonwealth paying interest on surplus cash as the Commonwealth generally provides it to the Authorities, in the first instance, free of interest. As there is no obligation on the Commonwealth to provide cash to the Authorities in advance of need, except at the end of the financial year, the best strategy would be to ensure that cash balances are not accumulated in the first place or that they are wound down before further cash is provided.

WHAT SHOULD BE DONE ABOUT VERY LARGE CASH BALANCES HELD BY SOME AUTHORITIES?

The government could indicate in writing to these Authorities that it was never intended that they accumulate large balances of cash (and financial assets) drawn from the Budget, and could seek their co-operation in returning surplus funds through one of the three options outlined later in this report (see paragraphs 12.1 to 12.8).

WHAT SHOULD ADMINISTERING DEPARTMENTS AND DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE SUPPLY DIVISIONS TAKE INTO ACCOUNT IN DETERMINING APPROPRIATIONS TO AUTHORITIES?

To accurately determine the annual cash needs of an Authority, it is necessary to obtain from the Authority an annual cash flow statement which would take into account the following:

- cash balances (including financial assets) carried forward;

- forecast revenue available to the Authority, including accounts receivable;

- forecast expenditure for the year.

To obtain a comprehensive picture of each Authority’s operational requirements, it would also be necessary to obtain information concerning cash forecasts for future years.

WHAT ABOUT SPECIAL “DEALS” WITH THE DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE?

Several Authorities have referred to unique arrangements that they have entered into with the Department of Finance — e.g., the National Gallery of Australia was allowed to draw down $3m to pay for building extensions well in advance of need, on the basis that it would not seek supplementation for cost escalation. ATSIC also referred to long-standing arrangements with Finance for drawing down its funds. The Task Force does not feel bound by any such “deals” but addresses this issue in this report. Specifically, it recommends a policy framework that would comprehend various categories of Authorities and the issues that have given rise to these piecemeal arrangements.

SHOULDN’T THE MANAGERS MANAGE?

One canard is that centralised financial controls might cause particular Authorities to lose some of their administrative responsibilities, hence contributing to the inefficiency of government. The argument runs that the managers should be allowed to manage.

A number of things can be said about this argument.

First, some Authorities are not managed well, from an overall cost of government perspective, if significant amounts of surplus cash are under-utilised.

Second, there is no proposal inherent in this Report that there be a return to the “old days”. The problem with “straw man” arguments is that the straw man has no brains.

Third, corporate treasury functions (beyond maintaining “normal” cash balances) are not and should not be a core business of the Authorities. Considerable management time and other resources can be diverted to such activities.

Fourth, it is interesting that, in the private sector, companies like BHP and Woolworths centralise their accounting and cash management responsibilities. While there are significant differences between the government and private sectors, including taxation requirements and the markets in which companies and governments operate — and those differences are relevant to sound cash management — there are some general lessons to be learnt. The Managers of Woolworth’s Big W or BHP’s Australian Iron and Steel do not appear to be handicapped by those “centralised” controls. They appear to get on with the job of managing their businesses. Those business units receive credit for their cash and pay for borrowed funds within the company “central” account.

Recommendation 1

The general principle governing the funding of Statutory Authorities which operate on their own bank accounts should be that payments to them are sufficient to meet their immediate cash needs and that they should not accumulate surplus balances of cash or financial assets as a result of early payment of Commonwealth monies.

Recommendation 2

Periodic payments to Statutory Authorities should be made on the basis of their immediate cash needs and the timing of such payments should therefore be carefully considered. There would be cash management advantages if they could be timed to coincide with Commonwealth revenue peaks each month and it is recommended that this be the norm.

The Cash Management Aspect of Funding Authorities

In the case of those Statutory Authorities and bodies that do not have their own bank accounts, i.e., operate directly on the CPA, expenditure is made directly by drawing cheques or electronic payments from the CPA and the funds therefore do not have to be raised by the Commonwealth in advance of need. It is preferable for Authorities to operate directly on the CPA, from a cash management perspective.

Authorities which have their own bank accounts draw public monies from the Commonwealth Public Account and pay them into their account, pending expenditure. Any such payment therefore represents an outlay from the Budget. Transferring the funds before the Authority needs to spend them will result in the

Commonwealth having to raise the funds earlier than necessary and therefore increases the PDI bill.

It is worth considering whether Authorities currently operating on separate bank accounts need to have this degree of financial separation from the Commonwealth, and this is certainly a question that needs to be addressed when new Authorities are being created. It may be that many Authorities would not be disadvantaged if they did not have the power to open and operate their own bank accounts. This would avoid the present situation where large aggregate balances are held in the bankaccounts of Authorities at a significant cost to the Commonwealth.

Authorities would argue that their need for independence is compromised by not having separate bank accounts. However, a large degree of flexibility and autonomy is available in using the Commonwealth Public Account.

Recommendation 3

In establishing Statutory Authorities, the Commonwealth should carefully consider whether there is a need for them to operate on a separate bank account, given the cash management costs of allowing cash balances to be held outside the Commonwealth’s aggregate balances with the Reserve Bank of Australia. Clear criteria need to be established. There should also be a review of those Authorities which currently have separate bank accounts to ascertain whether some could operate on the Commonwealth Public Account without detriment to their operations and need for independence.

Appropriation and Commitment of Funds

Many Authorities examined by the Task Force seemed to be of the view that they should be provided with cash, via Parliamentary appropriations, to cover their outstanding commitments. There was some evidence that the States took the same view in relation to SPPs.

The Task Force considered that this represents a basic misunderstanding of the appropriation process. The findings of the Task Force raise several fundamental issues concerning the nature of Budgetary practice that need to be clarified.

The first issue is raised by the fact that, in relation to payments to Statutory Authorities and SPPs to the States, Commonwealth monies have been appropriated and drawn from the Commonwealth treasury to meet program expenditure, in excess of cash need for that particular financial year. This is illustrated by the fairly common practice of providing, via appropriations, for the estimated annual expenditure of a Statutory Authority without taking into account cash carried forward by the Authority from previous years. Clearly, the cash carried forward is also available for expenditure in that year. In many cases, the full amount of the appropriation has been paid to the Authority within each financial year, allowing the Authority to carry forward large cash balances, year after year.

Similarly, with some SPPs, the amount of cash paid to the States clearly exceeds the amount that they are likely to spend in that financial year, with the result that they carry forward a surplus balance into the next financial year.

This cannot though be compared to the running cost arrangements, where a department is able to carry forward unspent funds from the previous year’s appropriation. The difference is that in the latter case, the cash remains in the Commonwealth Public Account until it is required for expenditure purposes, whereas in the former, the cash has been paid to separate entities.

The annual Federal Budget is clearly a cash Budget, covering receipts and payments for a given financial year. Given the cost to the Commonwealth of raising funds, and the addition to PDI that arises when funds are raised earlier than necessary, it is clearly inefficient to draw the funds from the treasury of the Commonwealth prior to need. Moreover, it could be misleading to Parliament if the Executive Government were to seek, through the annual appropriations, more than it expected to spend or more than was necessary to spend in that year.

Accordingly, the Budget presented to Parliament should represent the Executive Government’s best estimates of receipts and payments for that financial year. It should not seek to draw more than is necessary to provide for the services of government in that year as determined by the government. This does not imply that there should be a return to the examination of detailed estimates, or any notion of zero based budgeting. However, in pursuing current Budget practices, the government should ensure that appropriations are sufficient to meet current expenditure requirements only, i.e., they should not provide for forward expenditure and should not allow the recipients to accumulate surplus cash. In determining the needs of recipients such as Statutory Authorities and the States (in relation to SPPs), the estimates should make allowance for cash on hand carried over by Authorities and States from previous Budgets.

This arrangement should apply to the appropriations for Statutory Authorities and any other payments such as SPPs. Of course, some allowance would have to be made for reasonable working cash balances to be carried over where cash is drawn periodically from the Budget, such as for Authorities and SPPs, but these should be set at a level only to meet the ongoing operational requirements of the recipient.

This raises the issue of carrying forward of funding from one year to the next to meet future expenditure. It is important that Statutory Authorities and the States should have a sound basis for planning activities for future years. Accordingly, the government should indicate each year the level of forward year expenditure that it is prepared to support, for each Budget-funded Authority. (The situation relating to SPPs is dealt with elsewhere in this report.) To give added certainty to these approvals, the government may wish, in some cases, to formalise them in resource agreements, three-year rolling programs etc.

At first glance, it might be argued that these arrangements are already in place. However, it is clear that the way that the present arrangements work is far from satisfactory. For example, a number of Authorities have indicated that they consider it is correct practice for them to draw cash in order to cover commitments that will not mature until future years, or to provide for disbursements that they plan to make in future years. In the case of some SPPs, the agreement with the States provides for the Commonwealth to fully disburse the annual appropriation before the end of the financial year, even though it may be clear that the States will not spend the funds in that year. Similarly, with the three-year rolling programs agreed with some Authorities, these have been interpreted as guaranteeing the allocation of certain levels of cash over those years, regardless of whether the Authorities appear likely to need or to spend that level of cash.

In the case of capital expenditure, it has been a common practice among Authorities to draw cash from the Budget and set it aside to build up a reserve of funds for infrastructure replacement and other future requirements.

In each case, it would be possible for the government to approve levels of expenditure for future years, to give Authorities or States a sound basis for planning, without appropriating and providing cash for that expenditure in the current year. This would enable Authorities and States to enter into obligations or plan expenditure for future years, in the expectation that they will receive cash as and when required. The Task Force considered that there was a very strong need to change the basis for planning to the provision of cash when it is required.

It would assist the government to determine the level of annual appropriations to Authorities if Authorities were required to provide, in support of their estimates:

- business plans, setting out details of major activities and forecasts of revenue and expenditure;

- cash management plans, specifying the levels of commitments and other accruals due to mature in the current and future years and the timing of cash requirements to meet those maturing accruals;

- service delivery plans, which would indicate the levels of performance to be achieved during the year, including performance measures against which the Authorities would be held accountable.

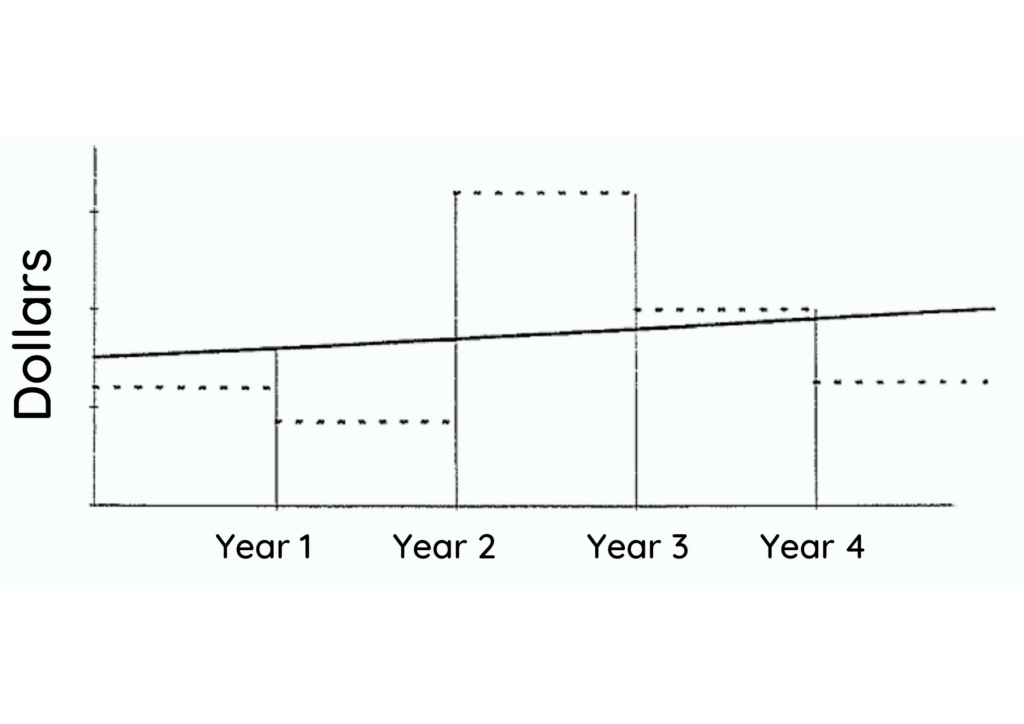

This proposal would avoid the need to draw down cash for expenditure in future years, e.g., for infrastructure replacement, and would have significant cash management benefits in the form of PDI savings. However, there would be a need for the change to be very carefully explained and for the process to be seen as binding on the Commonwealth, otherwise Authorities and the States will feel exposed to the risk of default and will attempt to continue with the existing “cash culture”. The effect of this arrangement is illustrated in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: Separation of Cash Appropriation from Current

Base Funding Over a Five Year Period

Current Base Funding Level ——— Actual Cash Requirement to be

met by Annual Appropriation

The solid line shows how the current base funding level for a typical Authority would be expected to increase in future years as a result of indexation to match cost increases. The broken line indicates how planned expenditure by an Authority might vary over those years, with year 3 indicating a large increase due to, perhaps, a capital outlay such as the purchase of a large piece of equipment.

Currently, the Authority would accumulate funds over a number of years to meet the large outlay in year 3. This would involve drawing down funds from appropriations years in advance of the need for those funds for expenditure — adding unnecessarily to the Authority’s cash balances over those years. It would be much better cash management for the government to provide the funds on a “just-in-time” basis. To overcome the problem, the government would agree to an expenditure profile over the relevant future years and agree to provide the funds up to that level, as required, in a ministerially endorsed resource agreement. This would give the Authority the degree of certainty necessary to plan future activities and expenditure, without drawing the funds from appropriations in advance of need.

Recommendation 4

The government should introduce a system of forward expenditure approval, which may take the form of ministerially approved resource agreements, for all Budget funded Authorities. The Budget papers should comprehend these agreements.

It should be possible for recipients to carry forward expenditure commitments into future years, thus avoiding the need to draw down cash in respect of those commitments until required.

Recommendation 5

The legislation providing for payments to Authorities and the States via SPPs should make clear that payments from appropriations will be made only to meet cash needs and that the appropriations need not he fully paid to Authorities or the States by the end of the year if the full amount of cash will not be required in that year. (Note: “cash needs” includes a reasonable level of working balance).

The Payment Process

Payments to Authorities are generally made fortnightly or monthly by the administering department, but in some cases they are made quarterly.

Many Authorities provide a schedule of cash requirements, mainly on a pro-rata basis with adjustments for any variations to their cash flows. There is little or no monitoring or review of these schedules during the year and payments are simply made on the basis of the originally agreed schedule. Authorities examined generally draw down funds for capital expenditure in equal instalments, without providing any forecast of when these payments will fall due, implying that they accumulate cash over a period of time to meet these costs as they arise.

The Authorities that have been examined have not been required to spend cash balances before drawing down their next instalment, nor have instalments been reduced in any way to allow for cash on hand or short-term liabilities.

There is currently a financial incentive for agencies to draw down cash from the Budget as early as possible during the year, so as to maximise their interest earnings on their unspent cash and investments.

The Task Force heard a view, put by officers of the Department of Finance, that rather than direct controls on cash draw-downs, the Task Force should recommend the implementation of incentives that would encourage Authorities not to draw funds in advance of need. The view was that direct controls run against the main thrust of the government’s management reforms.

While the Task Force accepts this view, it noted that there is an urgent need for remedial action in the light of the situation that has currently developed and considered that the government will need to rely on direct controls in the short term to ensure that cash draw-downs are more closely linked to expenditure requirements. It would take some time to develop and test a system of incentives that would introduce the level of certainty that is required to improve the timing of cash flows and be simple to administer. The Task Force did not consider that the government should delay in seeking the improvements that it recommends.

The relationship between the Executive Government and the Statutory Authorities should be similar to a contractual relationship for the provision of services. The Task Force considered that any system of incentives introduced to control payments to Authorities would need to be appropriate to that relationship. Payments to Authorities require a similar degree of monitoring and control to those applied to other contractors to the government.

Authorities are different from Departments of State in that they are separate legal entities and not part of the Executive Government. It is therefore appropriate that the provision of public monies to Authorities be more closely controlled than Budget allocations to Departments. The Task Force noted that as an interim measure, improved cash management could be quickly and simply implemented by administering Departments requiring Authorities to apply for each draw down by advising details of expenditure, receipts and cash on hand. An example of a possible pro-forma is at Appendix 5.

Recommendation 6

As an interim measure, each periodic payment to Authorities should be based on a cash flow statement to be prepared by the Authority taking into account cash on hand and forecast receipts and expenditure for the relevant period. In the longer term, the government should consider introducing incentives to discourage Authorities from drawing down payments from the Budget in advance of need.

The Timing of Periodic Drawdowns

In the case of large Authorities that are currently funded in monthly or quarterly instalments in advance of need, it appears feasible to provide fortnightly instalments. This would result in deferring the borrowing requirement until a time closer to need, thus reducing PDI. For example, ATSIC receives most of its program funding quarterly in advance. This could probably be rescheduled to fortnightly on the basis of need, providing this did not impede program delivery or add to program costs.

Cash Balances Currently Held

The Task Force examined in detail thirteen Commonwealth Authorities. The cash balances (including financial investments) of each of those Authorities, as reported at 30 June 1995, are indicated in Table 1, paragraph 6.2. It is clear that some of those Authorities have accumulated cash far in excess of their day-to-day operational requirements. In aggregate, their cash balances exceeded $700m as at 30 June 1995. It was claimed by some Authorities that these cash balances were fully committed against future expenditure requirements and could not therefore be regarded as being surplus cash. In other cases, the Authorities agreed that the cash balances were excessive.

In some cases, where payments have been received from private sources by Authorities to undertake specific projects or joint ventures, these receipts could be excluded from the calculations of Budget appropriations and cash needs. However, revenue generated by Budget-funded activities should not be excluded.

Some Authorities argued that they need the interest that they earn on their cash balances to supplement Budget appropriations in order to meet program objectives. It was suggested by some Authorities that they could pay back surplus cash to the Commonwealth and receive a payment in lieu of the interest that they would have received from investing the cash. The Task Force makes the following observations:

The cash balances held by Authorities could be utilised to reduce the Commonwealth’s net borrowings. It is anomalous that the Authorities hold large cash balances, which exceed their immediate needs, at a time when the Commonwealth has accumulated a large volume of debt.

The cost to the Commonwealth of allowing the Authorities to continue to hold these cash balances is equivalent to the net cost of borrowing an equivalent aggregate amount through the money market. Unless the cash is returned to the Commonwealth by, for example, reducing the level of funds appropriated to the Authorities, they could hold similar or increasing levels of cash in perpetuity. The interest rate which most accurately reflects the cost to the Commonwealth of allowing these balances to be held would therefore be the cost of raising funds over the longest period covered by Treasury Bonds, currently the ten-year Bond rate.

It is illogical for any Authority to claim that they need the interest on these cash balances if they are currently under-spending their annual appropriations. To use a metaphor, they would have to demonstrate that they needed the icing, even though they had not eaten the cake!

There seems to be no justification for the Commonwealth paying interest on the surplus cash balances of Authorities as the Commonwealth generally provides it to the Authorities, in the first place, free of interest.

If there is a genuine need to supplement the appropriations, it would be more economical to do so by increasing the level of the appropriations and paying the monies to the Authorities only when needed.

If interest was paid on balances clawed back to the CPA at a rate which reflected the cost to the Commonwealth of borrowing the funds (i.e., the bond rate), there would be no cash management saving. For there to be any saving, the interest paid would have to be less than the cost of borrowing.

While Authorities generally have wide ranging powers, these should be exercised in the pursuit of their core activities in the most cost effective way possible. It is not core business of the Authorities to act as investment bankers or money market dealers or to run substantial “cottage” treasury operations. The effective management of the large balances held by some Authorities would require the utilisation of resources that more appropriately should be used for core activities, and also divert the attention of senior management and the Authorities’ Boards/Commissions from those activities.

As there is no obligation on the Commonwealth to provide cash to the Authorities in advance of need, except at the end of the financial year, the best strategy would be to ensure that excessive cash balances are not accumulated in the first place or that they are run down before further cash is provided.

The Task Force identified various options for returning any cash balances that are considered to be excessive to the Commonwealth.

OPTION A: REDUCE 1996-97 APPROPRIATIONS

The most obvious and simple solution is to reduce 1996-97 appropriations to Authorities to allow for cash balances carried forward and to allow no further draw-down payments until cash levels had fallen to “working balances”. But for the legal difficulties outlined in Appendix 6, the full amount of the 1995-96 appropriations need not be advanced.

OPTION B: PAY SURPLUS CASH INTO A TRUST ACCOUNT

An option for some Authorities, if it was not considered appropriate to reduce their surplus cash balances, would be to require them to hold those balances, pending expenditure, in a Trust Account established under section 62 of the Audit Act. This would avoid the potential difficulties, political or bureaucratic, of clawing back the surplus monies to the Budget. However, it would involve a transfer of monies, which had been paid out of the CPA (Consolidated Revenue Fund) to the Authorities’ bank accounts, back to the CPA (Trust Fund). It could be argued that it would be better if the monies had not left the CPA in the first place, i.e., by adopting Option A (above) and reducing the annual appropriations.

If the Trust Account option was to be adopted in some cases, a decision would have to be made on whether to pay interest on the balances of the Trust Account(s). The decision should take account of whether the Authorities could demonstrate that they needed the interest. It would be difficult for those Authorities that had accumulated funds by consistently underspending their appropriations, to argue convincingly that they needed the interest. They have not even spent the appropriations which were available to them each year.

OPTION C: RETURN THE SURPLUS CASH TO THE BUDGET BUT ALLOW AUTHORITIES TO UTILISE IT FOR PROGRAM EXPENDITURE OVER THREE TO FIVE YEARS

Under this option, the government could indicate in writing to the Authorities that it was never intended that they accumulate large balances of cash (and financial assets) drawn from the Budget. Authorities would be required to submit detailed plans indicating how they would utilise the cash balances over the next three to five years, to achieve program outcomes. Pending the actual need for the cash to achieve these outcomes, the government could require the bulk of the cash balances to be “repaid” to the Budget by reducing the annual appropriations (as in Option A). Appropriations would then be allowed to increase during the three to five year period as the cash is required for program expenditure. At the end of the period, the level of appropriations would return to base level.

Recommendation 7

Where Authorities are considered to have balances of cash and financial assets sourced from the Budget or Budget-funded activities that exceed their immediate requirements, they should not receive further monies from the Budget until those balances have been run down to an agreed level.

In some instances it may be appropriate to require the Authorities to run down their cash balances, but to allow them to draw an equivalent amount from the Budget in future years, when the cash was actually required for expenditure purposes.

Adjust Appropriation Base Level

Some Authorities have accumulated large balances of surplus cash by underspending their annual appropriations over a number of years. Where this has happened, the level of the appropriation should be reviewed, to determine whether a structural adjustment should be made. The cause of the underspending may be administrative bottlenecks, overestimation of program parameters or a deliberate policy of withholding funds to develop a “nest egg”.

Recommendation 8

Where there has been a history of significant underspending by an Authority, there should be a review of the base level of the appropriation.

Government Policy Initiatives

Several Authorities and States referred to major government policy initiatives, under which they had been provided with large lump sum payments well in advance of need. These included the Australian National Training Authority and payments under the Building Better Cities Program. There is no need to provide Authorities and States with extra cash at the time these policy initiatives are announced. It would be better cash management for the government to simply approve additional expenditure by the Authorities, with the funds to be provided as required for payments.

Recommendation 9

When the government announces policy initiatives that involve providing for additional levels of activity by Authorities or the states, the cash to support those initiatives should not be paid in advance of need for expenditure.

Authorities that Distribute Payments on Behalf of the Commonwealth

Some Authorities examined by the Task Force have, as one of their major functions, the distribution of payments on behalf of the Commonwealth. For example, the Health Insurance Commission (HIC) pays Medicare benefits and the Childcare Rebate, Austrade makes payments in support of trade promotion and the Australia Council makes grants and payments in relation to the arts.

Each of these Authorities has large cash balances which could be returned to the Budget by the adoption of different payment arrangements. At 30 June 1995, Austrade had a cash balance of $195m, the Australia Council had a cash balance of $7m while the HIC, which is one of the largest Authorities in terms of its cash flow, had end-of-month cash balances which did not fall below $150m during 1994-95.

While it may be appropriate to provide these bodies with their administrative costs, the Task Force considered that it was unnecessary to pay the “benefit” component of the cash flows into the Authorities’ own bank accounts, pending payment to the final recipient. It would be much better cash management for the Commonwealth to retain the “benefit” component for as long as possible, rather than pay it into the Authority’s bank account.

In the case of HIC, which receives over $8b from the Budget each year, approximately $700m is drawn down monthly, most of which is subsequently disbursed to final beneficiaries throughout the month. There seems to be no practical need to pay the benefit component to HIC, as the payments could be arranged by HIC direct from the Commonwealth’s accounts. By retaining this money, it would be possible for the Commonwealth to defer borrowings until the payments were actually made to beneficiaries. In addition, the working balance of around $150m would be returned to the Budget. This would provide a one-off saving to the Budget of $150m and ongoing PDI savings.

Austrade clearly has surplus cash balances but even after these have been adjusted, it could operate on a very low working balance, if the program component of its current funding were retained by the Commonwealth. There would be similar, but much smaller, savings for the Australia Council.

Recommendation 10

The benefit or payment component of the appropriation currently made to those Authorities that disburse payments to final recipients should be retained by the Commonwealth, until the payment is actually made to the final recipient.

Other Categories of Statutory Authorities

The Task Force did not undertake a detailed examination of any government Business Enterprises, marketing bodies or industry research corporations which draw funds from the Budget. It noted from their annual reports that many of these bodies have very large balances of cash and other financial assets. It considered that a further review should be undertaken of these bodies to assess the reason for their high level of cash and determine whether there is a need to make policy changes in relation to the timing and amounts of their funding from the Budget.

Recommendation 11

A further review should be conducted of the funding arrangements of those GBEs, marketing bodies and industry research corporations that receive monies from the Budget.

Conclusion