Published in The Australian, 15 October 1996, p. 15.

Shusaku Endo, novelist, born Tokyo March 27, 1923, died September 29, 1996, aged 73.

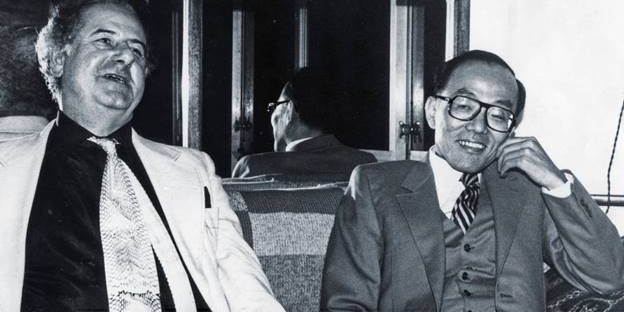

Graham Greene described Shusaku Endo, a Japanese who converted to Catholicism, as “one of the finest novelists of our time.” Irving Howe hailed him as “one of the most accomplished writers… living in Japan or anywhere else”, and A.N. Wilson said of one novel: “Endo is always a moralist, but When I Whistle shows him to be a great artist as well.” Endo, one of Japan’s leading writers, was well known. His novels were translated into 26 languages. He won all the major Japanese literary awards and was selected to the Nihon Geijutsuin, the Japanese arts academy. He published more than 20 works and also contributed to various newspapers and magazines in his country and, at one stage, had his own television show. He travelled on many occasions in the west. Endo’s best-known novel, Silence, sold several million copies in Japanese and in translation. Should film-maker Martin Scorsese’s plans come to fruition, the book will become a major movie. The English translation received extravagant praise upon publication and helped launch Endo’s reputation outside Japan. Silence, the story of a Franciscan missionary determined to sustain Christianity in Japan, following its prohibition in the early part of the 17th century, works at various levels. In those days, with a much smaller population, there were nearly 700,000 Christians in Japan. Endo tells of the interminable silence that torments a young priest anxious that some sign from above guide him in his mission. He asks: do the Japanese really understand God? Are the Christian concepts truly assimilated? Is it merely superstitious, the kind of religion the Japanese have taken from the missionaries? In the intellectual swamp of Japan, can Christianity take root? On one level it appears that the Japanese are unsuited to Christianity. But perhaps the problem is not so much the peculiarities of the culture as the fact that the westerners’ Christian convictions are unable to find root in the swamp of their own hearts, given the tests of the time.

Shusako Endo was born in Tokyo in the middle of the earthquake of 1923. At the age of three his family moved to the city of Dairen in Japanese-controlled Manchuria. In the early 1930s, his parents were divorced and his mother moved back to Japan with her two sons, living with a sister in Kobe. Following an aunt’s example, Endo’s mother became a Catholic and later, at the age of 11, Endo was baptized. Endo was never in good health – he was to undergo many operations, including the removal of one of his lungs. Accordingly, he escaped military conscription, but was required to engage in civilian war labour. After World War II he attended university and graduated in French literature from Keio University in 1949. Endo published various articles on literary criticism and some of his first short stories began to appear. In 1950, he won a scholarship to study modern French literature at the University of Lyon. After four years in France, he returned to Japan and, in 1954, won the Akutagawa Prize for his first novel The White Man.

He was troubled by the collusion between scruple and ambition, cowardice and everyday living, and the simplicity of the Christian message. Humiliation, shame, self-contempt, the result of self-abuse, and all the other feelings that cowards must live with in order to survive fascinated Endo. His novels explored the world of the weak and those points that cause a human to choose the unheroic. If Judas’s character held more interest for Endo than did the heroic, it was because he appreciated how difficult some of their choices were.

In his A Life of Jesus, he argued that the Western concept of Jesus and of God as a stern master was foreign to the Japanese.“In brief, the Japanese tend to seek in their Gods and Buddhas a warm hearted mother rather than a stern father. With this fact always in mind I tried not so much to depict God in the father image that tends to charactarise Christianity, but rather to depict the kind-hearted material aspect of God revealed to us in the personality of Jesus.” Later in the book, he comments: “We’ve come to recognise that concealed in the very fact of Jesus being ineffectual and weak lies the mystery of genuine Christian teaching. The meaning of the resurrection… is unthinkable if separated from being ineffectual and weak. A person begins to be a follower of Jesus only by accepting the risk of becoming himself, one the powerless people in this visible word.”

In Scandal, the lead character, Suguro, describes himself as a novelist: “A novelist who has to dirty his hands in the deepest recesses of the human heart. I have to thrust my hands in even if I find something there that God could never bless.”

In Endo’s view, religion was to be taken seriously, not literally. “From my own position as a novelist, I can’t say that creative composition is not to be equated with telling a lie,” he said.

English translations of his books include The Golden Country, The Samurai, Scandal and The Sea and the Poison, which explores the morality of Japanese doctors who conducted vivisection experiments on captured United States soldiers in World War II. The Girl I Left Behind is a partly autobiographical story about a heroic individual.

He also published When I Whistle, based on the three years he spent hospitalised; and Volcano, whose protagonist is an unfrocked Catholic priest. In one of his most charming and humorous novels, Wonderful Fool, he adapts the Resurrection story and a Japanese folk tale into a brilliant morality play, telling the story of Gaston Bonaparte, whose innocence and kind heart reshape the lives of those who knew him after his death.

Foreign Studies explores the painful isolation of a Japanese student in France in the early 1950s. The Final Martyrs contains short stories from the 1950s to the mid-1980. One of Endo’s last works, Deep River, concerns a visit to the Ganges by Japanese tourists.

Endo is survived by his wife, Junko, and their son.

Postscript (2015)

I never met the author, though I did briefly meet a brother, who was involved in the Japanese labor movement. I think he was employed somewhere in the nuclear power industry.

Martin Scorcese’s ambition to turn the novel Silence into a film is still on-going. At the time of writing, a quarter of a century after Scorcese first mused on the idea, the project is apparently coming to life.