This essay was written in September 2008 by a person previously in the employ of the Labor Council of NSW who intended to submit for publication. But owing to holding appointment to a senior role in public service decided to avoid any hint of political partisanship and therefore to refrain from publication. The article was sent without notice, after it was written, and on the condition of anonymity.

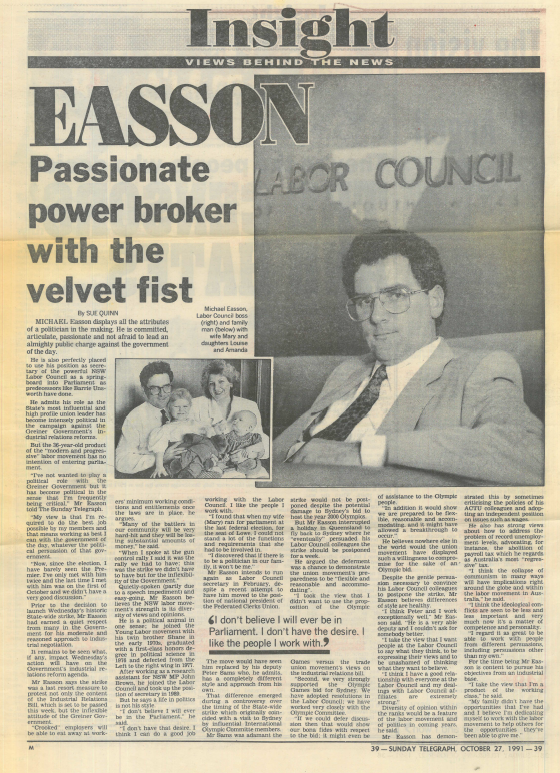

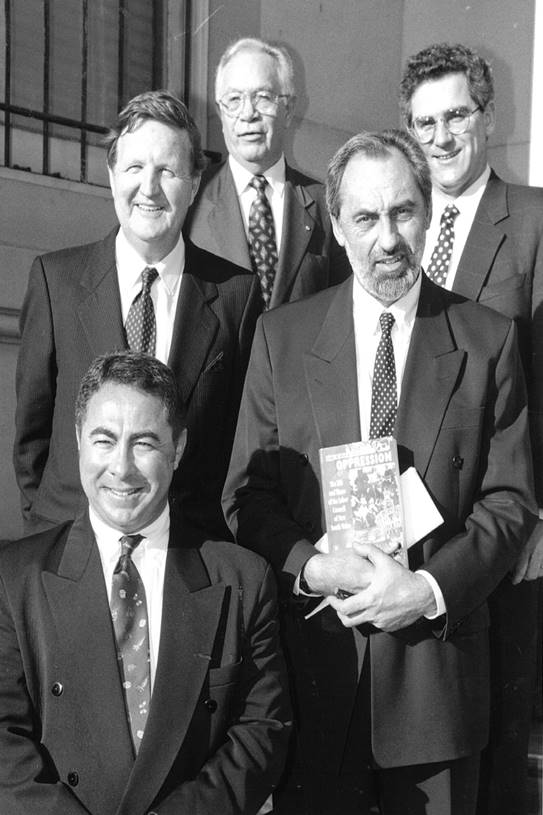

It is timely to revisit Michael Easson’s term as secretary of the Labor Council of New South Wales. Easson was the subject of criticism in some quarters during his period as secretary and criticisms have been aired subsequently.1 Easson’s style, role as secretary and political effectiveness need, however, to be seen in their own context – having regard to the exigencies of the time.

The first observation to be made is that Easson was the first secretary of the Labor Council who, in then recent history, had to meet the problems presented in, as leader of the State labour movement, dealing with a non-Labor government in New South Wales. Not only was Easson faced with a non-Labor government, the then newly-elected Liberal/National coalition under the leadership of the Hon. N. Greiner MLA (and subsequently the Hon. J. Fahey MLA) adopted an approach which was designed to diminish, or which would have had the practical effect of diminishing, the role of unions – albeit that such an approach had not been an explicit part of the Coalition’s pre-election platform.

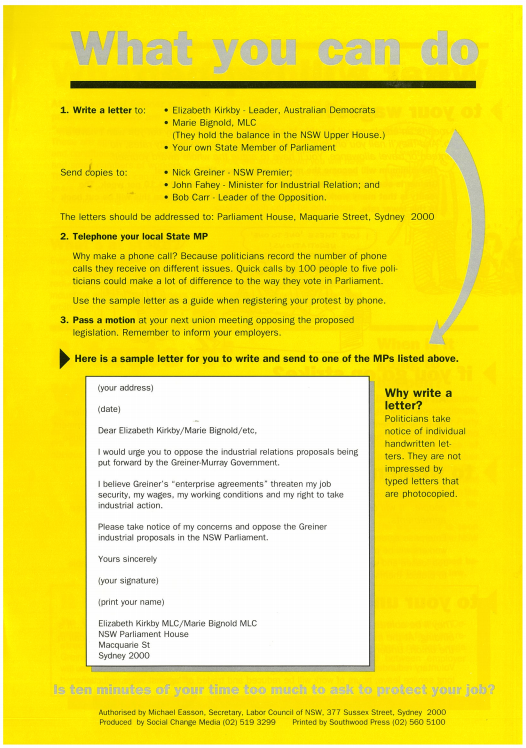

One of the first legislative steps taken by the Greiner government was a foretaste of what was to come. The government moved quickly to introduce the Essential Services Act 1988. At the time it was understood that a motivating factor in quickly introducing that statute was so unions effectively would be neutered as the rest of the industrial relations legislative programme was unfurled. Importantly, given what was to come later, some legislative changes were brought about to the Essential Services Act by way of Labor Council-proposed amendments that addressed at least some of the perceived legislative excesses. Those changes were the result of partly successful lobbying of the members of the cross-benches in the Legislative Council. At the time, the cross-benches comprised the Australian Democrats Members of the Legislative Council (MLCs), the Hon. Elisabeth Kirkby MLC, and the Hon.Richard Jones MLC, and the Call to Australia Party, the Hon. Rev. F. Nile MLC, the Hon E. Nile MLC, and the Hon. M. Bignold MLC. Amendments were forced on the government in the Legislative Council as a result of the Labor Council’s lobbying. Political lobbying of a style undertaken by the Labor Council with Easson as secretary had not been undertaken before by the Labor Council, or by other State-based or national union bodies. Shortly stated, in the late-1980s and early-1990s, it was then still a comparatively recent phenomenon for minor parties and independents to hold the balance of power in the New South Wales and federal bicameral parliaments. The lobbying by the Labor Council of the newly powerful cross-benchers was a role brought about by the demands of changed times – and, as is outlined later in this paper, the lobbying ultimately delivered successes in protecting the interests of the Labor Council and its affiliated unions’ members.

During the early stages of Easson’s secretaryship, the Greiner government commissioned two major inquiries for the purpose of shepherding-in legislative change. Professor John Niland was commissioned to undertake an inquiry into industrial relations and subsequently released a two-volume green paper titled Transforming Industrial Relations in New South Wales. A much lesser-known inquiry was also commissioned around that time concerning union finance-related matters. That report was usually referred to as the “Meagher/Heyden Report”, after its two barrister (later judge) authors Roddy Meagher QC and Dyson Heydon QC.

Niland had been one of the most consistent advocates in academic circles for a move away from a centralised system of conciliation and arbitration, whereas most industrial interests in New South Wales were comparatively content with the then industrial framework. Although some submissions to the Niland inquiry sought broad-reaching change, the overall tenor of the mainstream submissions advocated changes not that far removed from federal “Hancock”-style2 and Queensland “Hanger”-style3 approaches to changes to industrial relations in New South Wales. That is, the submissions to the Niland inquiry made by most mainstream industrial interests did not make calls for major structural or legislative change. Industrial relations practitioners, instead, were presented with Niland’s recommendations for a sweeping legislative and structural overhaul. The proposals flowing from the Niland inquiry recommended numerous changes designed to decentralise industrial relations in favour of a strong enterprise focus; to diminish the role of unions (and employer organisations); to “dis-establish” the former Industrial Commission of New South Wales, and otherwise to diminish its future role and influence; to establish a new Industrial Court, concerned with the application of “black letter” law; to introduce a USA-style “interests/rights” dichotomy; and to introduce a number of changes generally having the effect of constraining unions in a range of industrial/political activities. The Niland recommendations also placed a strong emphasis on the integration of anti-discrimination and EEO themes into industrial relations laws, which was somewhat ground-breaking and well-overdue at that time in New South Wales. For its part, the Meagher/Heydon Report proposed changes which were akin to treating union members as minority shareholders of public companies, and union officials as company directors, and recommended “oppression”-type provisions and financial accounting measures borrowed largely from corporations’ laws.

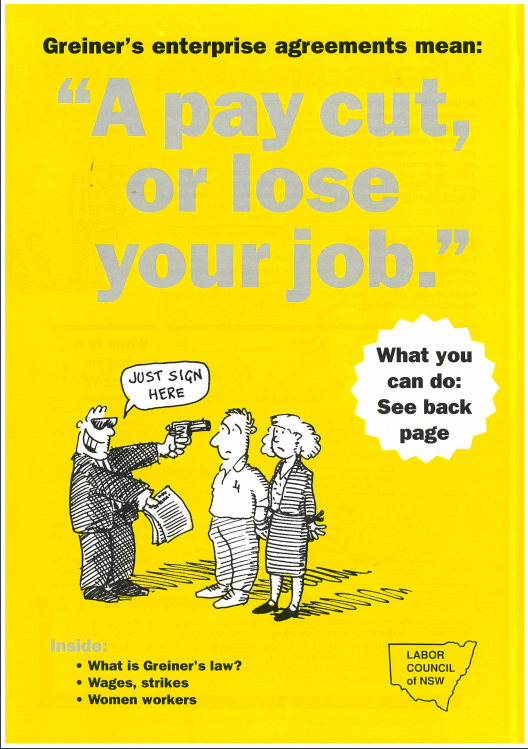

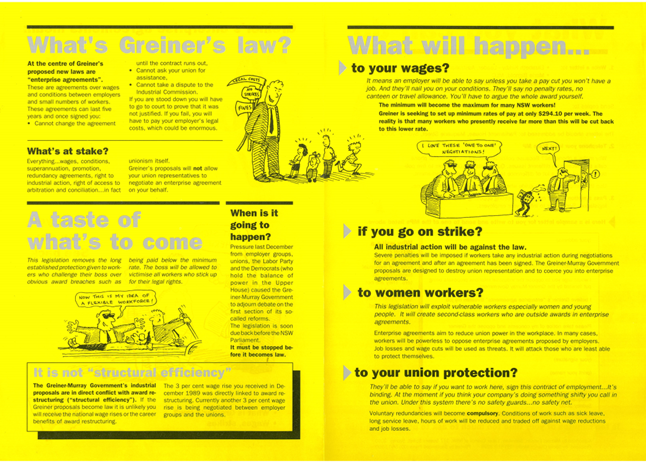

Although the Niland recommendations were antithetical to many issues close to traditional union interests, there was, nonetheless, a strong semblance of balancing of competing industrial interests in his proposals. That overall balance did not, however, see legislative form when the government introduced the Industrial Relations Bill 1990. The legislation was promoted by the government as designed to promote “greater flexibility” in the workplace; however, it was regarded, by most unions and academics at least, as having a transparently anti-union and anti-Commission bias.

It does not assist when examining history to use the language of hyperbole, but the changes to industrial relations looming during Easson’s secretaryship, quite simply, were unprecedented in New South Wales. There had been a stable structural and legislative framework in New South Wales’ industrial relations for the better part of a century and, to that time, governments were not perceived as attempting overtly to undermine the role of unions through legislation in the way adopted by the Liberal/National coalition in the late-1980s and early-1990s. It was, however, a time of change in industrial relations internationally: Margaret Thatcher’s 1980s had forever changed British industrial relations; and, more locally, New Zealand was undergoing significant industrial relations reforms which were delivering what, at the time, seemed to be substantial economic benefits. Greiner and Fahey themselves did not appear to be overtly personally hostile in their approach to unions, but the general legislative proposals and policy approaches adopted by the Coalition, nonetheless, were broadly antithetical to the pivotal role that unions and the Commission then occupied. There was real concern at the time among unions that New South Wales was being turned into a “New Right” industrial experiment for the deregulatory approach then being promoted by organisations such as the Business Council of Australia. (Some aspects of the changes which seemed so controversial at the time now feature in industrial statutes across Australia and, with the passage of time, appear industrially unremarkable. Moreover, it cannot go unremarked that, even in the late-1980s, there was support among some Labor Council officers and affiliated unions for adopting a greater enterprise focus and having a greater emphasis on collective bargaining – particularly for strongly unionised workplaces.)

There were different views among unions as to how best to respond to the mammoth Industrial Relations Bill 1990. Many union leaders strongly were of the view that the only appropriate response was one of outright rejection of the industrial relations legislation, coupled with a campaign of industrial action; but Easson embarked on a different approach. Acutely aware there simply was not strong enough opinion (among the public, media and cross-benchers) that the government’s industrial changes were so flawed as to be rejected outright, Easson adopted the difficult task of persuading affiliated unions that seeking modification of the legislation rather than seeking outright rejection, was the course most likely to yield practical, beneficial outcomes. Some decried this approach as a Labor Council “sell-out”; it was, however, a politically astute approach to adopt, given the prevailing environment, and an approach which was, with the benefit of hindsight and given the outcomes, arguably the best approach for the Labor Council. It would have assisted the government in seeking to enact its legislative reforms to be able to portray New South Wales as populated by militant and unruly unions sorely in need of sweeping legislative controls. Easson has been the subject of criticism that he was too accommodating of the government. In truth, the strategies Easson developed to combat the government’s intentions were, however, multi-faceted and sophisticated; and they did not give the government the pretext wanted – needed – to persuade wavering cross-benchers to pass the full range of legislation that would have adversely affected unions. In some ways, the approach adopted by Easson may be seen as a precursor to the effective “Your Rights at Work” campaign against the Howard government’s Work Choices legislation.

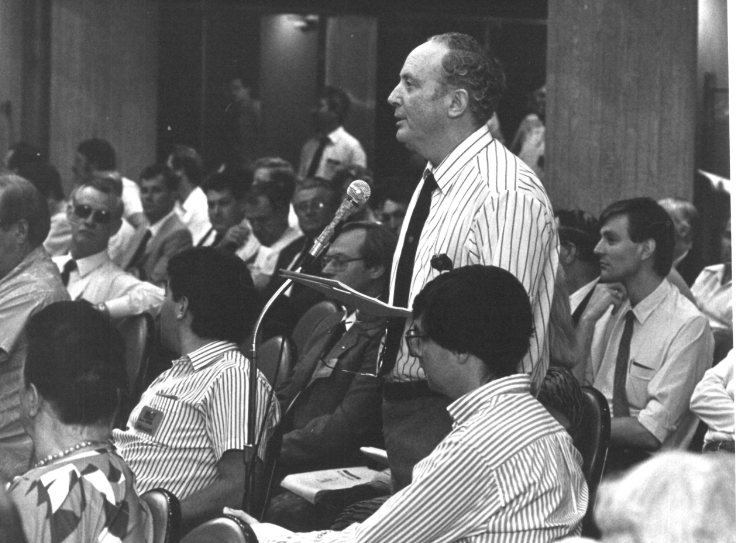

Easson deferred to the wishes of some unions by coordinating through his officers the traditional, in some ways industrially predictable, responses involving stoppages and disputation. The most notable manifestation of the Labor’s Council’s involvement in this respect was on 23 October 1991 the “Day of Outrage”, a state-wide strike accompanied by metropolitan and regional rallies.4 This was the first such strike in New South Wales since 1917 and, of itself, should neuter criticism that Easson’s Labor Council adopted a “soft” response to the government. Although union membership numbers were at historically low levels, the rallies in Sydney and in regional centres were attended by decent-sized numbers and the day was an industrially symbolic event. Ultimately, however, the Day of Outrage was of no real suasion in terms of changing the government’s legislative agenda; in some senses, it gave the government some leverage for adopting a “hard line” response.5

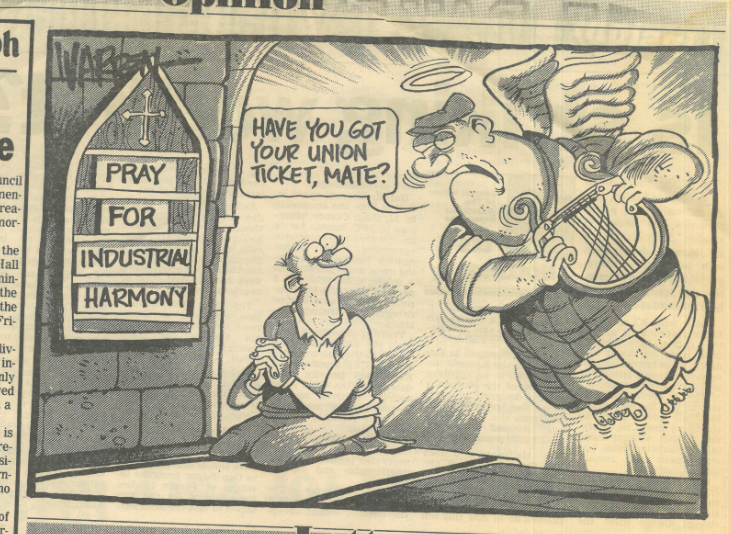

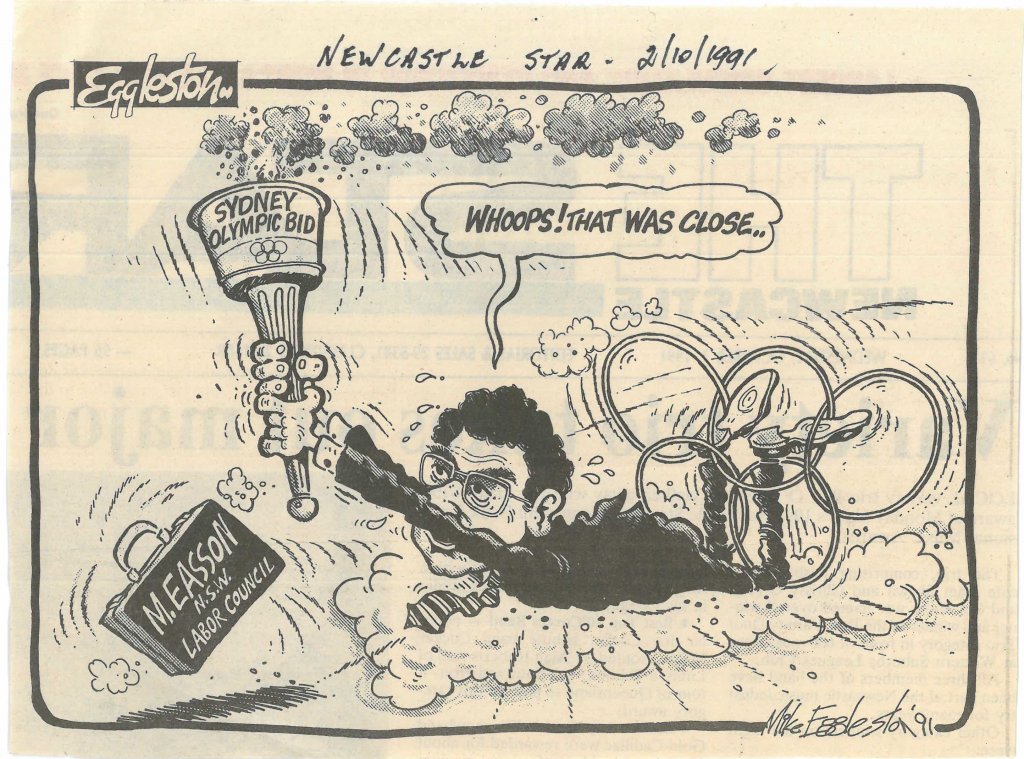

What proved more important in real, as opposed to symbolic, terms was the way in which Easson went about corralling opposition to the legislation and otherwise raising broad community concern about the proposed industrial relations changes. Naturally enough, most in the union movement needed no persuading in opposing the changes. But Easson also conferred with registered employers’ organisations and major employers, and successfully highlighted concerns employers might have about the practical operation of the legislation. Many employer interests were, quietly at least, generally content with the existing industrial framework and had no wish for significant change; a number of major employers said as much to the government. Easson contacted academics and journalists to encourage them to articulate in print and in other media concerns about the changes. Around this time, Easson established a labour-minded “think-tank”, the Lloyd Ross Forum, to ventilate a perspective different from that being promoted by, for instance, the industrially conservative H.R. Nicholls Society. He prevailed upon a wide range of people to contribute to the written debate, including the then President of the Industrial Commission, the Hon. W.K. Fisher AO, who contributed an article in a Lloyd Ross Forum publication.6 Easson authored articles himself, aware that the industrial relations debate was being run – and hopefully would be won – on various levels.7 Easson ran an expensive advertising campaign in newsprint and on radio, which spilled-over into talk-back radio and opinion pieces; generally media-savvy, Easson personally cultivated the journalists who wrote such pieces and their editors. Easson rallied support from organisations such as the Australian Council of Social Services, by highlighting the effect the changes would have on those who were already socially and industrially disadvantaged. Easson similarly contacted churches and successfully prompted churches to voice concerns about the legislation. Easson even invoked the Pope, by arguing that the legislation was antithetical to a papal encyclical concerning social justice. In short, Easson worked every available angle – and then some – against the government’s proposed changes.

Easson faced an industrial and political environment different from that experienced by all comparatively recent Labor Council secretaries, and a criticism levelled against Easson was that he was not as closely involved as other secretaries in the ALP hierarchy. It cannot be said that the interests of the union movement and the ALP necessarily coincide; the differences between unions and ALP governments over workers’ compensation are visceral examples in that respect. While it may have been generally beneficial, however, for Labor Council secretaries to have high-profile offices and involvement with the ALP at times when the ALP was in government, such a role was generally contra-indicated during the Greiner and Fahey administrations. It would not have assisted in lobbying members of the cross-benches in the Legislative Council for the secretary of the Labor Council and the ALP to be effectively indistinguishable. In the case of Easson’s secretaryship there was a clear political imperative for some greater “product differentiation” between the Labor Council and the ALP, so that the respective organisations and their interests could not be portrayed by the Coalition as “one and the same” or self-serving, particularly in relation to sensitive financing issues. Union funding of political causes and parties is a traditional irritant to politically conservative interests, and such issues were being reviewed by the government when Easson was secretary, e.g., the Meagher/Heydon Report recommended changes which would have allowed individual members to take court action to seek to restrain a union from giving funds to, say, the ALP or for some political cause.

Easson built strong lines of communication with the members of the cross-benches in the Legislative Council and, by all accounts, was personally well-regarded by them. Easson effectively put himself and the staff of the Labor Council at the disposal of the parliamentarians, day and night, in the event they wanted any questions answered or information provided. The lobbying was personally customised by Easson and spearheaded by him; the day-to-day lobbying and negotiating was cross-factional, being conducted by more junior Labor Council officers – often in the company of officers of left-wing unions, particularly Daniel Reiss then of the Building Workers’ Industrial Union. Apart from the broad lobbying campaigns, Easson developed ways of individual lobbying of members which itself was finely focused. For instance, the former actor, Elisabeth Kirkby, was lobbied by Easson in the company of representatives from Actors Equity and the socially conservative members of the Call to Australia Party were lobbied by Easson in the company of prominent, Church-minded, conservative unionists. Members of lobbying delegations were even instructed by Easson not to smoke cigarettes while at Parliament House (at a time when smoking was still permitted in the building), for fear of alienating the vote of the vehemently anti-tobacco Democrat MLC Richard Jones. As a follow-up to parliamentary votes, Easson urged affiliated unions and their members to write letters of thanks to the parliamentarians, to profile them in articles in their union journals – and to make sure that the parliamentarians received copies of the articles.

The Industrial Relations Bill 1990 was, at the time, the longest legislation that had been introduced into the New South Wales Parliament. The government used its numbers to gag debate in the Legislative Assembly, but by the time the Bill had finished in the Legislative Council, it was the most heavily amended Bill in the history of the Parliament with over 300 amendments.[8] The amendments prepared by the Labor Council were moved and articulated on the floor of the Parliament principally by the then shadow Minister for Industrial Relations, the Hon. J.W. Shaw QC MLC.

It may be noted that Easson’s legislative strategy was not one which was merely reactive to the government. For instance, Easson, in conjunction with the Democrats and with the agreement of the ALP, arranged amendments to the Industrial Relations Bill which represented the first legislative attempt to grant paternity leave and adoption leave rights in Australia, following upon the test case decision of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission in the Parental Leave Case (1990) 36 IR I. The Minister for Industrial Relations, John Fahey, who was a member of the Legislative Assembly, made the rare step of taking to the floor in the Legislative Council to personally debate the legislation and the proposed amendments. There were so many amendments that they were moved, several at a time, en globo. Despite the effective and well-informed debate by Fahey on the changes, important divisions were lost by the government on the floor of the Legislative Council. The amendments were successful in key strategic areas; the Bill was gutted. The strategy developed and implemented by Easson in response to the Coalition’s proposed legislative changes had proved to be effective.

Some piecemeal industrial changes subsequently were introduced in a series of bills colloquially referred to as the “bite size chunk bills”, with varying measures of success. The bills were diluted versions of some of the central changes that the government had unsuccessfully tried to enact.

The campaign against the legislative changes over which Easson had presided was so successful that the government, frustrated by comment that it lacked electoral mandate for the changes and by the inability to enact the industrial relations changes, called an early election to seek a mandate on industrial relations reforms. The government was re-elected. When the legislation was reintroduced on 28 August 1991 as the Industrial Relations Bill 1991, after an election called by the government on the specific basis it could not have its industrial relations changes enacted, the proposed industrial changes were modified in some significant respects. The government was aware that, even after calling an election based on seeking a mandate for its industrial relations policies, it would not be able to push all its legislative programme through the Legislative Council. What was left of the government’s initial proposals became the Industrial Relations Act 1991. This too was complicated in its attempted comprehensiveness: “The Bill was the largest piece of legislation ever introduced into [the] NSW parliament, being some 333 pages and 750 clauses.”9 That statute was widely regarded as having been both cumbersome and ineffective, and there was not much real or sustained enthusiasm among even the employer ranks for the changes introduced by the government. The industrial parties endeavoured to skirt-around the new legislation and conduct industrial affairs much as before – witness, for example, the emergence of “splinter awards” to avoid the legislative difficulties in varying awards during their nominal term. Indeed, it was not uncommon during the Easson years for the Crown to initiate appeals in the Commission about approaches that had been developed cooperatively by the Labor Council and employer interests.

On any fair analysis of it, Easson had demonstrable successes in the strategies he oversaw to attack a legislative agenda which was regarded as antithetical to unions, workers, and the Commission. The media reported the eventual form of the legislation as involving qualified wins for unions and, with the passage of time, that view still holds.

Apart from opposing changes to industrial laws, Easson’s Labor Council was also heavily involved in opposing the government’s proposed changes to WorkCover and TransCover. The workers’ compensation and insurance changes were regarded as highly contentious and were opposed by unions and the legal profession. The lobbying coordinated by Easson saw the Labor Council, the Law Society and the Bar Association in an unusual partnership jointly prevailing upon the cross-benchers to reject the government’s proposed changes – although, it must be said, with entirely different purposes. Once again, Easson coordinated a multi-faceted campaign opposing the changes. A media campaign was mounted, and the Labor Council organised a major rally outside Parliament; and, once again, Easson personally tailored the lobbying of the cross-benchers. For instance, when it came to light that some MLCs were the parents of police officers, Easson arranged for the Police Association to form part of the lobbying delegations and used examples of what may occur to police officers injured on duty. The MLCs were personally introduced to workers who had suffered catastrophic, work-related injuries and showed the parsimonious payments they would receive under the ‘Table of Maims’ – which set a scale of fixed money amount for specified classes of injuries. At various points, Easson persuaded the ALP to organise a filibuster in the Legislative Council for the tactical advantage of buying more time, so that the government’s intention with proposed legislation could be frustrated. In August 1989, for example, on workers compensation reform, the ensuing debate resulted in the longest unbroken sitting of the Legislative Council, spreading to 27 hours. The Labor MLC Mike Egan quipped: “To my knowledge the only other institution that keeps the hours this House has kept over the past 24 hours is a brothel. …this House – the oldest legislative Chamber in this nation – is in danger of becoming a house of ill repute.”10 Although passed by the Legislative Assembly in April 1991, the Workers Compensation (Benefits) Amendment Act 1991 did not pass through all stages by the end of the sitting term. The government was, however, resolute that the parliament would not rise until its worker’ compensation changes were forced through the Legislative Council. Sleep-deprived and weary, the cross-benchers were persuaded by the government that the costs to the State of the existing workers’ compensation arrangements would leave the New South Wales in penury. With various legislative initiatives over several years, most of the government’s wishes were eventually implemented but not, it must be observed, without the vehement opposition from the Labor Council.

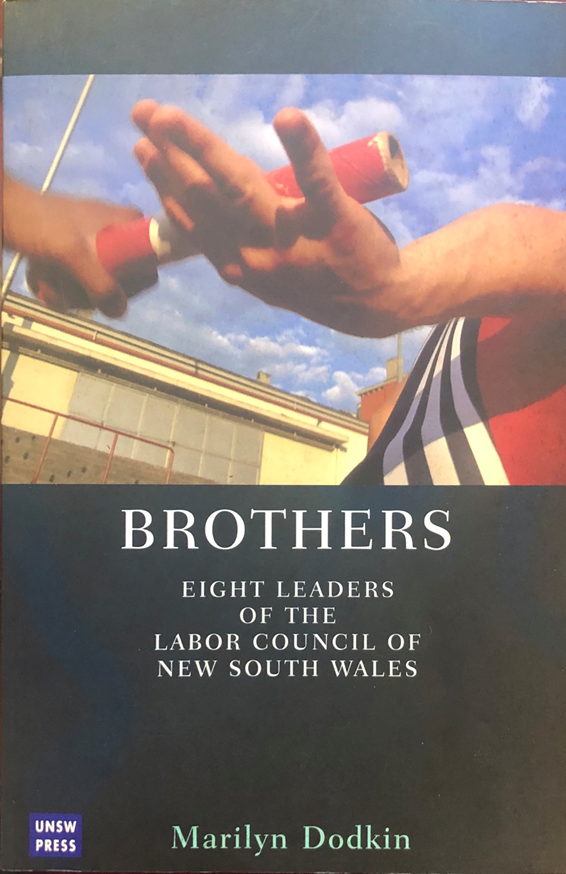

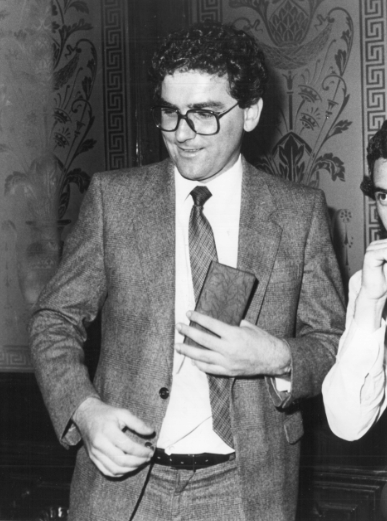

Easson encouraged the exchange of ideas and policy development among the employees and officers of the Labor Council and would enjoy playing devil’s advocate or putting people to proof as to why he should be persuaded to one view over another. In that context, it is troubling to see the assertion in Brothers that a Labor Council employee was made a “sacrificial lamb” for expressing views that differed from the prevailing ACTU line. Similarly erroneous views still seem to have currency as recently as 2008.11 Easson publicly supported the right of Labor Council staff to hold and express their own views on matters of policy, including the views espoused in a controversial policy discussion paper authored by two officers who were then employed by the Labor Council, namely, Mark Duffy and Michael Costa. The views expressed by Costa and Duffy were not of concern to Easson: the paper had been the subject of strident discussions when it had been presented at an in-house conference of Labor Council staff and officers. When the document was printed in the newspapers – resulting in criticism of Costa and Duffy from a range of high-level unionists and Labor politicians – Easson rejected outright the calls made to dismiss the two officers. While Easson did not associate himself or the Labor Council with the ideas expressed by Costa and Duffy in their discussion paper, Easson defended their prerogative to hold views different from the then dominant ACTU orthodoxy and laughed off concerns as to their suitability to continue working at the Labor Council. It was, however, a matter of understandable concern to Easson that an internal policy discussion paper had been leaked to a newspaper, particularly given the political sensitivity of some matters canvassed in the paper. A committee of senior members of the Labor Council’s Executive was convened by Easson to investigate how the document came to be printed in the newspapers. It was later reported in the media that Duffy had given a copy of the paper to a trusted colleague; the dismissal was concerned with giving an internal document to a person outside the Labor Council, and withholding that fact from Easson, not with its contents.

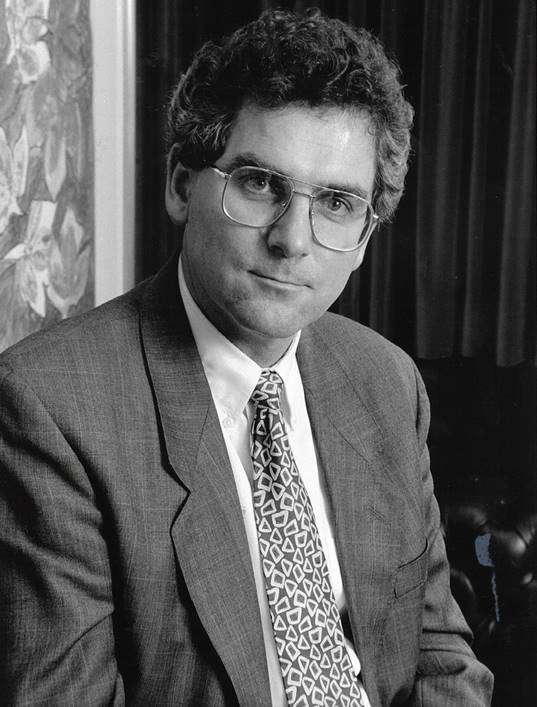

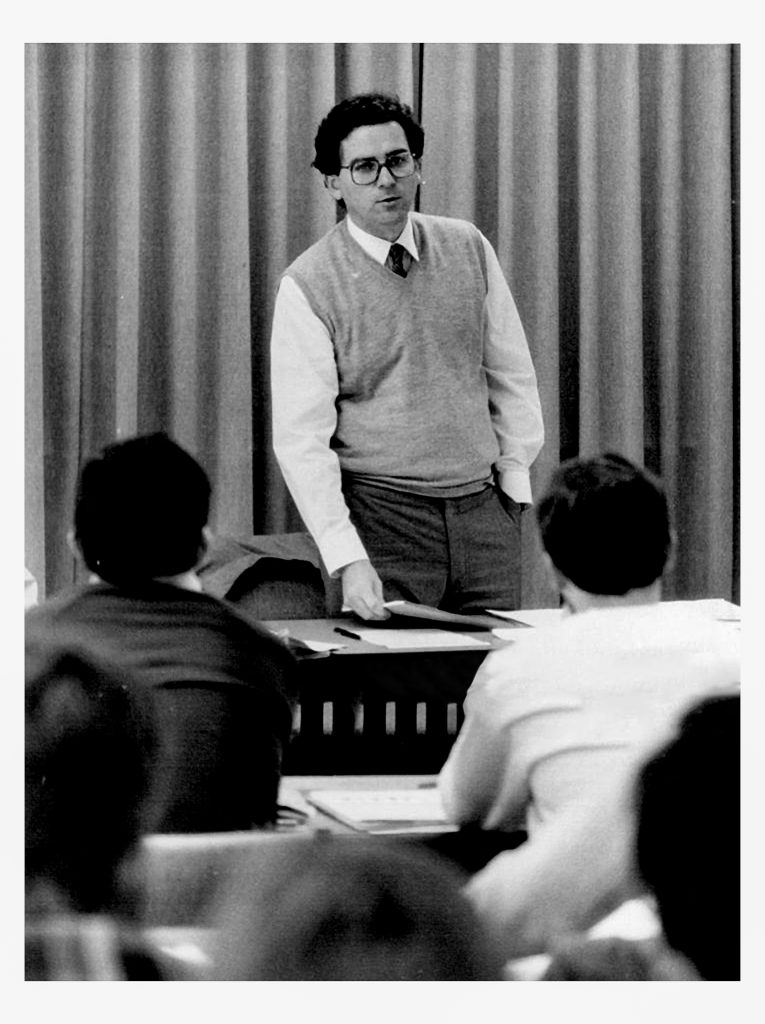

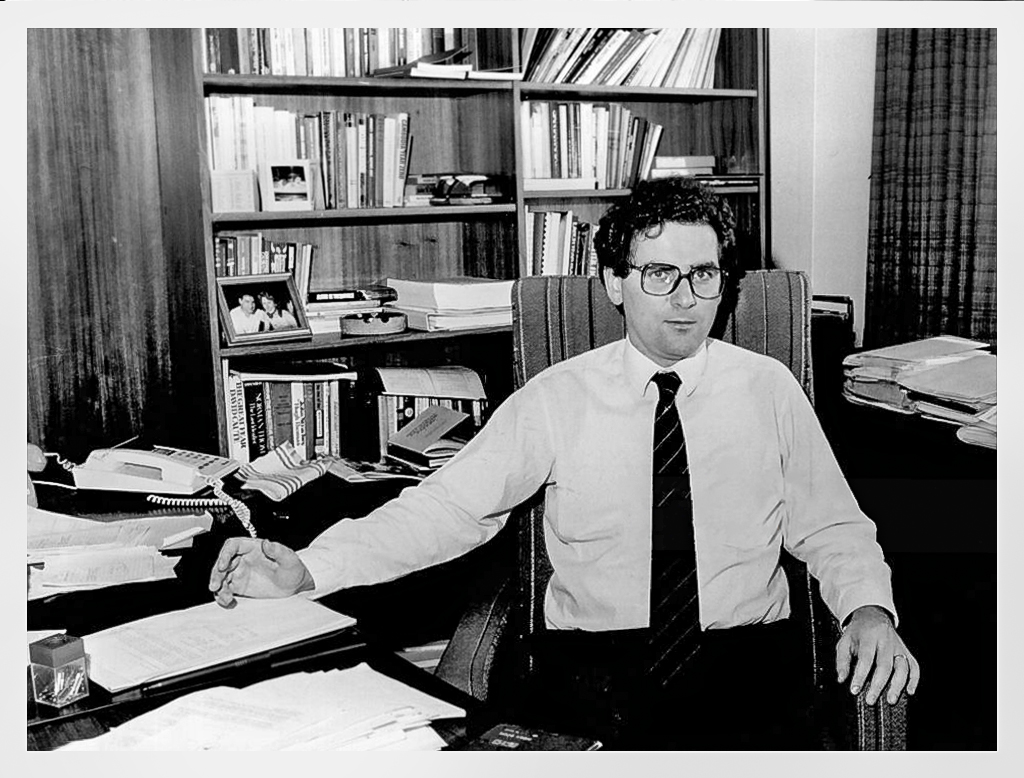

Much has been made of the fact that Easson is a man with strong intellectual leanings who, while secretary, cultivated interests beyond the Labor Council itself – sometimes in tones suggesting that this was somehow a bad thing. Ray Markey, in his history of the Labor Council of NSW said of Easson:

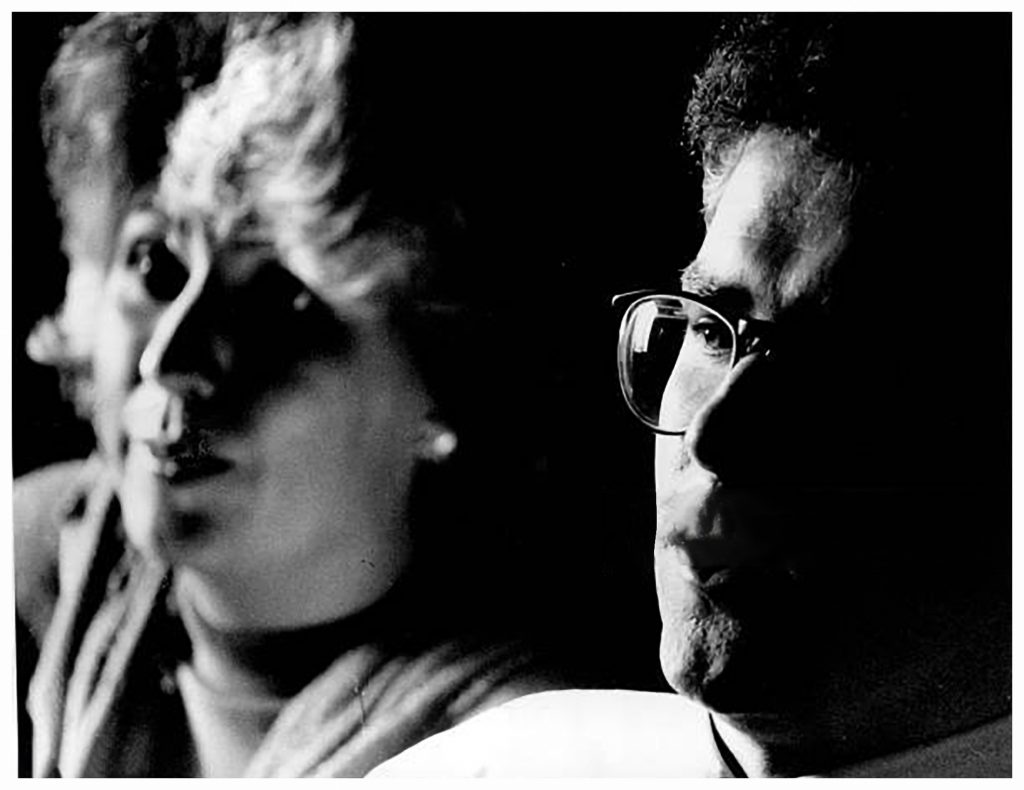

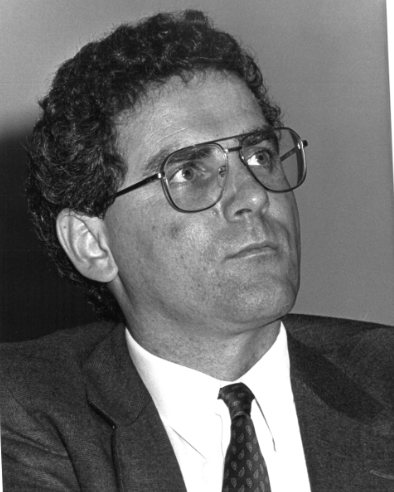

[He] was willing to consult with factional opponents to a degree which sometimes unnerved his own factional supporters. Yet, as with his predecessors, Easson possessed a toughness which did not allow him to be easily taken advantage of, despite his relatively softly spoken style, and the almost ‘bookish’ appearance lent by his glasses and thick dark hair.12

Easson openly encouraged the development of new ideas and strategies among officers at the Labor Council, and among affiliated unions. Easson earned a considerable degree of personal loyalty from many of the people who worked with him as staff and officers at the Labor Council because of his willingness to listen to them and his concern about trying to do the right thing, coupled with his inherent personal decency. As part of Easson’s “hands-off” managerial style, decisions typically were left to the individual judgment of the officers in question. Easson once said, memorably, that if you could not be trusted to make an appropriate decision on your own, then you should not be working at Labor Council in the first place.

Other Labor Council secretaries have received praise for broadening the right wing/left wing union and ALP political base of the staff and officers. For his part, Easson encouraged the involvement in Labor Council-related activities of those whom he regarded as talented, largely irrespective of their political affiliation within the left/right political spectrum. He took the issue of broadening the Labor Council’s own staff base much further than any secretary before him by employing a person who was closely connected with the Australian Democrats, namely Armon Hicks. Easson also involved Labor Council officers and employees in issues which went beyond the strictly industrial, but which were entirely compatible with precepts of general social justice. Easson was particularly strongly committed to the interests of political prisoners and refugees and was well-known for circulating among staff (and sometimes to affiliates) human rights articles from local and international journals. Consistent with the broad approach taken by Easson to the extra-industrial role of the Labor Council, Easson, with the able coordination skills of his executive assistant, Tom Forrest, organised a rally in the forecourt of the Sydney Opera House to welcome Nelson Mandela to Australia. The rally was attended by crowds estimated at 100,000 and was rightly regarded as a marked success.

Easson’s period as secretary ultimately had a troubled conclusion, involving financial difficulties, staff retrenchments and a failed tilt for political office – being matters which are not addressed in this paper as they have been well canvassed elsewhere. The assessment of Easson’s secretaryship, in what I would contend is an unbalanced way, has focused on that conclusion rather than on what was achieved during the whole time he held office. Shortly stated, Easson’s achievements as Labor Council secretary, in an environment more politically hostile than that encountered by the secretaries who preceded him, have not been properly acknowledged. This paper may provide a different perspective. As another former Labor Council secretary, John Ducker, noted when asked about his judgment on Easson’s term: “I think it is true that the circumstances of the time that people are in have an enormous effect. You’ve got to be relevant, you’ve got to be tuned in, so each of these periods mark a distinct contrast.”13

Notes:

1. Dodkin, M., Brothers – Eight Leaders of the Labor Council of NSW, UNSW Press, Kensington, 2001.

2. A reference to the Hawke Labor government’s appointment in 1983 of a Committee of Review of Australian Industrial Relations chaired by Professor Keith Hancock which reported in 1985. Hancock concluded that the systems which had served Australia for nearly eight decades were fundamentally sound though saw merit in moderate changes, including the development of arrangements to allow parties to ‘opt-out’ of awards in some circumstances.

3. A reference to a Committee of Inquiry review of industrial relations law and practice in Queensland led by Ian Hanger QC which reported in November 1988.

4. See articles in the Sydney Morning Herald at the time, e.g., ‘It’s a State of Chaos’, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 October 1991 and all issues of the paper that week.

5. Cf. ‘Greiner: I Won’t Give In’, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 October 1991, p. 1; Lansbury, Russell D., ‘The Harder Edge of Industrial Relations: Legislation That Provoked a General Strike in New South Wales on 23 October 1991’, Directions in Government, Vol. 5, No.10, November 1991, pp. 16-17.

6. Fisher, W.K., ‘The Green Paper: A failure in Consultation?’, in Transforming Industrial Relations, Pluto Press, 1990, pp. 109-116.

7. See, for example, ‘Industrial Relations, the Grinning Mirror, and Inflation’, in Transforming Industrial Relations, Pluto Press, 1990, pp. 53-74.

8. Griffith, Gareth, ‘The New South Wales Legislative Council: An Analysis of Its Contemporary Performance as a House of Review’, Australasian Parliamentary Review, Vol. 17, No. 1, Autumn 2002, p. 59.

9. Dawson, Neale, ‘Industrial Reform in NSW. Economics Before Workers’ Rights?’, Legal Service Bulletin, Vol. 16, No. 6, December 1991, pp. 284-5.

10. NSW Legislative Council, Hansard, 2 August 1989, p. 9118.

11. See article by Alex Mitchell in [the website] crikey.com 7 May 2008.

12. Ray Markey, In Case of Oppression. The Life and Times of the Labor Council of New South Wales, Pluto Press and the Lloyd Ross Forum, Leichhardt [NSW, Australia], 1994, p. 416.

13. Dodkin at 196.

Postscript (2020)

I received this manuscript “out of the blue” from someone who used to work closely with me. It was gratifying to see a positive assessment.

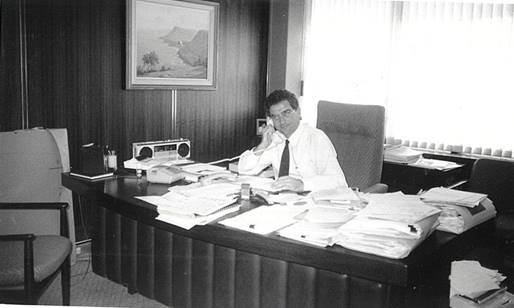

With this revised michaeleasson.com website going up, this prompts me to account for my time in the Labor Council of NSW (renamed in 2004 as Unions NSW), the circumstances that led to my election as assistant secretary, then secretary, and the five years I spent in that role. An earlier prompt came in June 2019 when I did an interview with Pat Garcia, the then NSW ALP Assistant Secretary, who told me he wanted to interview me for his PhD as he had me down as the “technocratic” Secretary. “Ahuh”, I thought. I am not sure what he meant by the term, and I am not sure if he did either.

No doubt in what follows in this Postscript, blind spots, defensive embellishment, and self-aggrandisement will be readily apparent.

When I became assistant secretary of the Labor Council of NSW in 1984, aged 29, it was completely by surprise. The pea for the job was shot out the door. A rethink occurred on what and who was needed. Chris McArdle was the Labor Council organiser groomed for the role. He was a university-educated former Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) national industrial officer. Feedback on his performance at mass meetings of unionists, on delegations to employers and NSW government ministers, on various industrial matters, was mixed. Sometimes his wise-cracking personality put off people. I thought he was industrially astute, but Unsworth who was closer to the “action” than I was at the time decided that the “supercilious bastard” had to go.

That gave me my chance, not that I had a clue that I was under any kind of consideration for the job. I had never lobbied against McArdle. I had not sought promotion. I got on well with him. (An exception to my assessment arose from the shock of reading his 1982 draft report on a union delegation to China, which he led. I had to completely rewrite the document to qualify, deny, and tone down various passages uncritical of the Chinese regime. His report was later published as a pamphlet.)

Unsworth one day walked into my office and announced his decision. More or less, I was told: “He’s going and you can be our candidate. Are you interested?” That was a shock. Naturally, the assistant secretary, John MacBean, Unsworth’s successor-in-waiting, had to decide if he wanted me on the ticket. He thought about other options. (Years later I discovered that John Grayson, then an industrial officer with the Public Service Senior Officers’ Association, was another person considered. He would have made a good appointment.) MacBean settled who should be his assistant secretary. An election of all the delegates to the Labor Council needed to be held at the February 1984 annual general meeting. I was dispatched to see the various union secretaries to canvass support. Unsworth and MacBean made introductions. A caucus of moderate unions unanimously endorsed me as the right-wing candidate. Overwhelmingly, this was because of affection for Unsworth and MacBean and trust in their judgement.

Some union leaders saw me as an ideological heir to Unsworth, others as a good complement to MacBean, and others as a hard-working youngster who was worth punting on. A few more thought I was an inexperienced greenhorn who was a gamble for the role. Those views sometimes overlapped. Certainly, I was “green” in day-to-day “industrial relations” experience. Would I grow into the job? The majority view was “yes”, which explains the wager.

Why was this happening? What prompted Unsworth to move out of a full-time role at the Labor Council? This had to do with NSW ALP politics.

Following a hotly contested decision by the 1979 NSW ALP conference to admit members of the NSW Legislative Council (MLCs) into the NSW parliamentary Labor caucus as full voting members, Unsworth had to decide on a career in full time politics or relinquishing his position as a MLC. That was because Premier Neville Wran insisted as part of the quid pro quo that after future NSW state elections, the MLCs needed to be full time; previously they were part-time.

Unsworth, elected as a part-time MLC at the 1978 NSW state election, was torn about what to do. In 1984 he faced re-election. He had to decide either to go full time in politics and resign from the Labor Council or not stand again. He loved the union movement. But he felt that the NSW government did not sufficiently appreciate its industrial base. Some conflicts between the government and the unions in health, transport and the electricity sector, for example, were avoidable or could have been managed better. He knew reforms were needed in many areas and he thought he could make vital contributions as a senior minister. He leapt to the plunge. (Years later, both of us unawares that a few weeks in June 1986 Premier Neville Wran would resign and Unsworth would be selected as the new NSW Premier, Barrie was frank about the choices made. He missed the camaraderie of the movement. “Here”, pointing around the NSW parliament building:

you are on your own. Everyone in their own forts, hoping you fall over. There’s a lack of loyalty, of comradeship. You don’t talk much with your colleagues. At the Labor Council we had more in common with the left than most people here. You felt part of a movement. The politicians think of themselves.

That made me feel at the time even more of the view that full time elected politics required unusual temperament and stamina. I questioned whether that could ever be me — thinking later, that in comparison, Mary Easson was a natural for politics.)

In the nearly six years prior to my election as assistant secretary in 1984, I worked at the Labor Council as Education and Publicity Officer, but mainly as Barrie Unsworth’s executive assistant/gofer/researcher on all things. I had no idea where I might go to next, other than a view that hopefully it would always be with the labour movement. I had given up interest in ever becoming an academic. A reason for this commitment was that the Labor Council had been kind to me.

In 1981, I was selected to go to the then 13-week Harvard Trade Union Program at the Harvard Business School, and then a US Leader Grant to visit unions and conferences on US industrial relations, industry organisation and Democratic politics, and then to the United Kingdom to spend 3 weeks with the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Union (EETPU), then led by Frank Chapple (1921-2004), the heroic ex-communist turned right-wing UK Labour supporter who wrested control of the union off the communists in the early 1960s.

A significant investment in my development was made. I owed the movement big time. In 1994 at a function to mark my time at the Labor Council I offered a toast to the paranoia of the left at that time. Perhaps if no Harvard, no subsequent role as an elected Council Officer.

Two asides: on selection to Harvard in 1981 and on how I saw my role. First, my Harvard selection was a fluke. Judith Walker (1938-2001), NSW Secretary of the Australian Insurance Employees Association (later merged into the Finance Sector Union), was picked. Her national secretary, however, forbade her to go; he alleged that a course taught on one of the most liberal campuses in the United States was a CIA-front. In her place I went. Barrie Unsworth walked into my office that July and asked what I was doing in September. I flew out – my first overseas trip – after the 1981 ACTU Congress that month. (Judith became a Vice President of the Labor Council in 1982 and a full-time MLC in 1984, retiring from politics in 1995. On her parliamentary web page, in her list of recreations she included “classical music, reading and listening to peers with a sense of history.” She was tough, funny, and never forgot where she came from.)

Second, I saw my role at the Labor Council as a vocation. Others in the movement had similar perspectives. We thought we were making the world a better place and we had a responsibility to serve a higher cause. Some on the right in the Australian labour movement were religiously motivated in thinking that way.

On my return to Australia at the end of January 1982, I wanted to hone my skills in industrial relations and deepen my knowledge of industrial relations law. I enrolled in a Diploma of Labour Relations and the Law which was taught in the early evening at the Law School at the University of Sydney, then located on Phillip Street in the city. In first year (of a two-year period of part time study) I passed one subject with a HD but was refused permission to sit the exam for the other, as I physically had not been present for 60% of the classes. My absence mostly due to attending meetings after hours for the Labor Council. Unsworth had launched the “rubber chicken offensive”, urging that Labor Council officers and union leaders speak at community gatherings on why unions mattered. (“Rubber chicken” being the moniker for the typical meal served at such events.) I approached numerous Lions, Apex, Rotary, and other clubs with the offer of a guest speaker. More than half the time, as others were busy or had too little notice, I was the person to turn up. I was single (not marrying Mary until November 1984) and therefore freer than most.

I read the labor law lecture notes (others had copied theirs for me.) So, exam or no exam, from my studies and from the weekly Council meetings and other activities of the Labor Council, I generally was on top of most areas of NSW and Federal labour law. The related politics I knew from avid interest.

Quid Pro Quo

As earlier stated, my selection as the Labor Council officers’ choice for assistant secretary of the Labor Council of NSW was announced in late 1983 and there was overwhelming support (such was the regard for Unsworth by most of the right-wing union officials in NSW, rather than any particular merit of my own.) There was some surprise and anticipation by parts of the left that I might be vulnerable to dissenting right wingers upset at McArdle’s removal from contention. But that did not prove to be the case.

Of that moment in time, Meredith Burgmann wrote in a column on “Australian Trade Unionism in 1983”, Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 26, No. 1, March 1984, pp. 95-96:

In New South Wales, the Labor Council remained firmly in the hands of the right, but problems arose within its own ranks. With the removal of Barrie Unsworth to the state political arena, the obvious candidate for secretary was John MacBean. But who was to replace MacBean as assistant secretary became the burning issue, highlighting particular problems of the right wing of the New South Wales union movement. Over the past few years, the Labor Council has been recruiting as its full-time officials ‘bright young men’ with untested ability and little or no rank-and-file experience of trade unionism. Consequently, in this instance, a choice had to be made between a senior organiser who had not performed up to expectations and a more junior colleague who had no trade union experience at all. The inexperienced candidate was chosen and the senior organiser offered a post as State conciliation commissioner. Whether the loyal supporters of Unsworth and MacBean will accept an assistant secretary who they perceive as a ‘young student’ with no trade union background remains to be seen.

It was not fair to say I had no union experience; I had already six years in the Labor Council. In working part time during my university degree, I loaded and unloaded trucks at Ansett Freight Express and was a member of the Transport Workers’ Union. But it was true that I was not steeped in years of practical industrial relations. My age was against me. There was no use pretending what I was not.

In February 1984 Stan Sharkey, NSW Assistant Secretary of the Building Workers’ Industrial Union (BWIU) ran against me, and I won with about 70% of the vote.

With the ALP, usually the Labor Council Assistant Secretary joined the NSW ALP Administrative Committee and took on a major role in the top leadership of the party. But I did not. At the end of 1983/early 1984, Stephen Loosley the General Secretary of the ALP, NSW Branch, wanted me to give up editing LaborLeader, the ALP right journal and to handover the running of the McKell Schools to whomsoever he appointed. Unsworth agreed. He thought “quid pro quo”. He counselled not to be greedy and take on too many roles. Let Loosley run the ALP, MacBean was President of the NSW ALP Branch (replacing Paul Keating in 1983) anyway; my role was to support MacBean. As assistant secretary of the Labor Council my loyalty was to the union movement, rather than the ALP. Make that choice, concentrate on that, was the message. In all the circumstances, this was the right advice.

I missed running the Schools, originally called Social Democrat Schools, which were started by Bob Carr in 1976, then moved to me to run from 1978-1984 after I replaced Bob at the Labor Council. The Schools blooded into the NSW ALP right the young and new activists, and involved lectures on party history, contemporary issues, economics, foreign policy, and media training. We typically met on a weekend at the Women’s College at the University of Sydney. Thirty years later, Chris Bowen MP told me that we first met at one of those weekends, when he was a senior high school student.

It was an excellent way to acculturate promising talent into a wider movement, enabling networking with like-minded souls. We discussed policy, including the challenges of economic and industrial relations reforms in the lead-up to and the early days of the Hawke government.

The Schools eventually reduced in number and turned into lectures on “campaigning”. Discussion and debate on policy issues diminished, eventually fading from view. (I suspect this is relevant to the decline of the NSW ALP right as a powerhouse of ideas. This, however, is a complicated topic best addressed separately – if at all, another time.)

Those developments I followed rather than with any active involvement.

As Assistant Secretary

As assistant secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, I convened meetings of the rail and transport unions, the maritime sector, the steel industry, sometimes the metal unions, the building trades, etc. Peter Sams, as the senior organiser, dealt with major matters before the Industrial Relations Commission of NSW and the federal tribunals. As did I from time to time. Familiarity with the procedures and personalities I needed to learn; but once that occurred it was not as daunting.

Notwithstanding factional allegiances and the “past” of officials at the Labor Council, we all tried to be fair, as objective as we could, in dealing with competing interests of unions, especially demarcation disputes (disputes over union coverage, where one or more unions competed for membership.) We were seen by nearly all the unions, Left, Right and independent, as reasonable.

I respected the leadership of the old Building Workers’ Industrial Union (BWIU) – in particular, the NSW secretary of the union, Stan Sharkey. His somewhat cantankerous deputy, Don McDonald (1938-2018), was more difficult but sincere. (After Don McDonald died, I sent a message of sympathy, which was read at the memorial by his brother Tom McDonald. I said: “I always liked Don: tough, argumentative, sometimes hard to take, but a man of great honour, principled, a heart of gold: One of the great characters of our movement, one of the best of the old BWIU. Tremendous campaigner for schizophrenia research.”)

If you did a deal with one of whom we used to call the “ocker Stalinists” (the working class, pro-Moscow union leaders), it stuck. (Post-merger into what became the Construction, Forestry, Mining Employees Union, the CFMEU, the more recklessly militant from Victoria and Western Australia, eventually gained control of many of the state branches. That occurred post my time at Labor Council.)

Labor Council and the ACTU

With the ACTU, MacBean preferred that I minded the fort in Sydney, especially as nearly all the ACTU Executive meetings were in Melbourne. Each state was represented on the ACTU executive through their Labor Council or Trades and Labor Council. I was John’s alternate, from 1984/85. After John’s election in 1985 as senior vice president of the ACTU (which meant he held an ACTU executive position in his own right), John nominated Jim Walshe, secretary of the Australian Railways Union (ARU), NSW Branch, and a vice president of the Labor Council, to serve on the ACTU executive as the Labor Council representative from 1985-1989. I was Jim’s alternate. (Jim regarded Lloyd Ross, one of those retired unionists I most admired, as a sometime mentor and model of an innovative union leader. Though, like most of Ross’ allies in the ARU, he thought Ross stayed too long as secretary and saw his backing in 1969 of a communist as his successor as sadly odd.) I liked Jim as one of the best people I ever met in the movement. A twinkling eye, a sense of the absurd, and an Irish lilt immensely improves your chances of being listened to!

I observed from a distance those matters discussed at the then regular ACTU Executive meetings which met at least four times a year stretched over a full week.

That therefore left me as the acting secretary in Sydney, conducting the regular Thursday night weekly meetings of the Council which, most weeks, attracted 150-200 delegates from unions. I spoke at Labor Council meetings and grew in experience. Knowing I was a slightly serious character, John Whelan (1934-2015) from the Commercial Travellers Association, later merged into the National Union of Workers (NUW), recommended that I tell a joke at the beginning of each meeting. Everyone would then relax. Some good and bad jokes were told – how many times the laughter was with or at me I could not say. But at least they were laughing!

Several things I thought about were financial services and extending superannuation coverage and benefits in the private sector.

From 1984, I was a Labor Council representative on the Public Authorities Super Scheme, which in 1988 merged with State Super. The latter was once the largest superannuation fund in Australia. I learnt more on those boards than anywhere else. I thought the Labor Council should seek a role in the development of superannuation. At one time in the mid-1980s, I put to ACTU Assistant Secretary Gary Weaven (the ACTU officer primarily responsible for setting up the major industry superannuation schemes) that I could get the NSW Employers Federation, the Chamber of Manufactures of NSW, and ourselves to set up a NSW default scheme. “If you do that, you can have NSW,” he said. I am not sure Weaven could deliver, but that was his offer. In NSW, however at that time, there was a lack of appetite. I was told some unions wanted a pay raise for members rather than more in their “super” account. Phil Holt, the head of the Chamber of Manufactures, was enthusiastic. They owned an insurance company, Manufacturers Mutual, and were commercial. The head of the Employers Federation of NSW, Garry Bracks, on the other hand, was dismissive. “Michael, these people do not have a clue. The idea of handing money over to inexperienced union thugs is unthinkable. Make no mistake: by the end of the year, Weaven or one of his mates will be in jail.” He had a way of making definitive statements. He thought that the building industry super fund would end in tears. The “shock and awe” training of his mentor, Alan Jones (his immediate predecessor as head of the Employers Federation), was to the fore in making this wild claim. The early industry “super” funds were understandably paranoid about the potential for discrediting probity lapses and were mostly conservative in their evolution and investment strategies. Balancing boards with 50% employer representatives blocked or tempered the more stridently ideological positions.

In any event, my idea of a NSW statewide scheme was stranded, eventually coming to fruition in emasculated form well after momentum was in the sails of the first industry funds. Good luck to them, I thought. In 1988 Brack said he would agree to a default scheme, which we agreed with the Chamber (after brand marketing advice) would be called Asset Super, that would only take 3% contributions, the then minimum award standard, but not more (which therefore in my time at the Council excluded award or enterprise agreements with higher contributions, thereby stunting the growth of Asset Super. In 2012 with $1.6Billion under management, Asset merged with the larger industry fund Care Super.)

Tensions with the ACTU

There were tensions between John MacBean and the ACTU leadership on union amalgamation and industry policy, and even with Paul Keating. When Barrie Unsworth was defeated as Premier of NSW in March 1988, the Greiner government ministers foamed about industrial relations reforms, privatisations, sackings of public servants, reductions in employment in key authorities, such as rail and electricity, removal of union-related directors from NSW government authorities. As President of the NSW Branch of the ALP (having succeeded Paul Keating in 1983) and as Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, MacBean was criticised as “too political” by the new government.

With the ACTU’s dominance in setting the direction of union strategy, even sometimes directing traffic to and from the Treasurer’s office, MacBean’s previously close relationship with Keating frayed. I wrote for John a detailed analysis of the ACTU union amalgamations/rationalisation strategy and its long-term implications for the Labor Council of NSW. (And I kept updating that analysis in the years ahead.) My conclusion was that the political complexion of the unions would change, potentially over time depriving the ALP right in NSW of its majority. The implication being that we had to change or perish, potentially admit some lefties to the leadership (a vice presidents, the finance committee, perhaps one full-time official) to lower the ideological temperature. The Labor Council officers needed to win stronger support from some unions in growing sectors of the workforce, the healthcare and nursing sector for one, to survive, renew, and continue our traditions as the moderate ballast of the Australian union movement and as practical, social democratic reformers.

On manufacturing industry, MacBean had a more protectionist bent than what was popular in Canberra. Keating saw him as “not understanding tariff policy” or the changing economy. MacBean thought Keating had become arrogant and out of touch.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I was involved in many meetings and negotiations on redundancy and structural change. Manufacturing was shrinking. It was satisfying in some instances to negotiate generous packages, including vocation training, extended notice, and generous severance arrangements in industries as diverse as clothing & textiles, whitegoods, tyre manufacture, food processing, railway workshops, etc.

At a rowdy, early morning meeting of workers at a shutting-down section of a cigarette manufacturing site owned by WD & HO Wills at Pagewood in Sydney, Glen Batchelor, a left-wing organiser of the Plumbing Trades Employees Union, quipped to me afterwards that our training in Young Labor had prepared us well for the meeting we had just held. We were used to being shouted at and holding our nerve. (I had the added advantage of being half-deaf. Interjections did not rattle me much. I rarely heard them clearly!)

In late 1988, John decided to quit for appointment as a Deputy President of the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. I sensed that he was traumatised by the tensions with Keating, and separately with Kelty on the union reform agenda, and upset at the NSW election loss and its implications. We had goodwill towards each other, though I was never as close to him as to Barrie, who was like a father-figure to me.

Ironically, with Keating and the left unions, MacBean played a major role in bringing them closer, at least to a position of wary respect. In 1985 when Keating was promoting comprehensive tax reform, including a consumption tax, MacBean convened a meeting of all the major unions at the Labor Council. The leadership of the building, maritime, metalworkers and other big unions were in the room, Tom MacDonald, Tas Bull (1932-2003), Laurie Carmichael (1925-2018), and others, writing-pads in hand, furiously noting everything said. It was one of Keating’s better days, as he sought to justify the overall package as progressive, fair and of overall net benefit to the working poor. He was defending Cabinet’s endorsement in May 1985 of a draft white paper on options for tax reform. The paper recommended “Option C” – a reduction in marginal income tax rates offset by a broad-based consumption tax. For many of the left union leaders, more than a few of them members of parties to the left of the ALP, they were meeting Keating for the first time and in a convivial environment. As one of the communist leaders, the Federated Engine Drivers and Firemens’ Association’s Jack Cambourn (1928-2015) told me at the time, he saw that Keating had “a framework” to think about policy and to judge its utility. This was a revelation to him and others.

Stay Neutral

MacBean asked one thing of me: that I stay neutral in the looming NSW TWU ballot, due in early 1989. In fact, he said everything depended on my complying. John thought he could guide the relationship with the likely incoming leadership, and we needed to play a delicate game. He too realised the stakes. John had got close to Harry Quinn (1918-2008), the NSW Secretary of the TWU who in 1983 suddenly succeeded Ted McBeatty, drowned in a boating accident. In 1988, the Sydney sub-branch secretary of the union, Ted Edwards, was running to succeed Quinn, with the latter’s support. Edwards was someone MacBean thought we could work with and rely on, despite his closeness to some figures on the left. I am not sure what staying neutral meant, as the Labor Council officers no longer had any slush funds to assist in union campaigns. This was deliberate. The right-wing ALP officers now filled that vacuum.

One Sunday in December 1988, I drove to St Clair, to meet Steve Hutchins (1956-2017) at his home, to express my moral support. I knew Steve from our days in Young Labor. I had asked John Tolley (1944-2014), an industrial officer at the Labor Council, to privately help in the campaign and to do that for me. Donations were raised, Tolley told me, but that all went to the ALP slush fund to support the John McLean (for secretary)/Steve Hutchins (for assistant secretary) ticket for the TWU, NSW Branch. In March 1989, the McLean ticket won. The victorious ticket leaders thought I had done nothing for them. Henceforth, Hutchins was mildly hostile. He had gone to school with John Della Bosca, Michael Lee (a member of the Keating Cabinet), Seamus Dawes, and was then great mates of Della. There were a close-knit group.

Tolley wanted me to name him as my candidate for Labor Council assistant secretary instead of Peter Sams. I refused. Tolley left the Labor Council early in my term as Secretary. He was a fine man, whom I learnt a lot from, including calling another’s bluff.

(I remember one night when I was acting secretary, early on a Thursday night the evening of the weekly meeting of delegates to the Labor Council, Mary called in hysterics as she had seen a mouse running around the house and we had a young baby, Louise. I could not abandon Labor Council, or so I felt. I despatched Tolley. He drove to Ashfield, where we were living next to an old-fashioned convenience store, bought a mouse trap, and asked Mary for peanut butter and a carrot; he sliced off a small piece smothered in peanut butter and set the trap. Before I had got home that night — snap! — the target caught.)

In the election in February 1989 for Labor Council secretary, I was opposed by Brian Beer, NSW assistant secretary, Amalgamated Metal Workers Union (AMWU), now the Amalgamated Manufacturing Workers Union. He was a dour figure, on the Labor left, progressive, thoughtful, self-educated — the type of person you were thankful for the movement producing and developing. I won with over 65% of the vote.

Peter Sams became my deputy as assistant secretary, Beryl Ashe the senior organiser (the first woman in that role), together with Michael Costa (the first non-Anglo-Celtic elected at the Labor Council) and Mark Lennon as the other elected organisers. Tolley decided to leave and joined LinFox, the transport company, in Melbourne.

A team of talented people formed around me. I encouraged everyone to think for themselves, challenge my view in our discussions, and never stop thinking.

Ten Challenges

There were significant challenges:

First, the Labor Council needed to re-evaluate its role in the light of changes to the Australian and NSW industrial relations systems, including the political, economic, and organisational landscape.

Second, and related to this, the ACTU was busy restructuring the unions with little internal challenge or dissent.

Third, union membership levels were in steady decline. Could the Labor Council play a positive, pro-active role in reversing decline and assisting recruitment?

Fourth, the Labor Council had become irrelevant to the superannuation and financial services sectors. Was there a useful role to play?

Fifth, the distinctive voice of the Labor Council in the affairs of the Australian labour movement was in danger of being muted or unheard, as the movement was rapidly evolving. (I thought at the heart of this challenge was the need to have something to say in the first place.)

Sixth, an economic recession was unfolding.

Seventh, effective financial management loomed as vitally important due to the economic downturn and because the Labor Council was unprepared for the cutback in funded positions by the state government to the Council.

Eighth, the wholly owned radio Station 2KY was brimming with potential administration and financial challenges.

Ninth, a new conservative government in NSW claimed a mandate for industrial relations “reform” — the kind that would weaken affiliated unions. What strategies and tactics were merited?

Tenth, and related to the last point, there were many calls, not just from conservative circles, for changes to the Australian (and NSW) industrial relations system. That required careful examination.

I relished dealing with those ten challenges.

Getting Our House in Order

On the first challenge, the issue of the Labor Council adapting to the times, I encouraged the staff to debate issues and ideas about what should be prioritised. I then refined those ideas and subjected them to challenge and the development of fresh-cut insights with a sub-committee drawn from a cross section of unions. At the 1990 Labor Council Annual General Meeting, I reported with these observations:

1. The growth in federal award coverage had become considerable in many industries; for example, only from the mid-1970s have the building and metal industries become primarily federal award areas.

2. State Commissions had become less and less important as pacesetters and as ‘players’ in the overall system. The national tribunal was now easily the most important industrial tribunal in the land. Its guidelines were usually adopted with minor changes by the state tribunals. This trend has accelerated since 1975 and the onset of a more centralised system.

3. The NSW Industrial Commission — the historic innovator in fields such as long service leave, penalty rate arrangements, pay equity, redundancy and other benefits — had now become a conservative backwater. Unions regularly complained about the pettiness and intransigence of senior members of the NSW tribunal when it comes to the task of administering industrial assets.

4. Unions have considerably expanded their resource base and this trend has accelerated with union rationalisations and amalgamations.

5. The Labor Council’s affiliation fees allow it to have a resource base equivalent to the size of a union with less than 15,000 members.

6. The ACTU had grown over a decade from a small show — one full time president, one secretary, one research officer, one industrial officer and various support staff — to a large secretariat of the national union movement.

7. With union rationalisations, there should be fewer demarcation disputes requiring the assistance of the Labor Council.

8. With larger unions being created through merger and amalgamations, those unions increasingly prefer to do their own things.

Labor Council had to fit within and adapt to the parameters created by those factors. More of the same would not do. The Labor Council would (hopefully) always be a forum for debate in NSW and could also prompt, nudge, guide, and initiate action for the betterment of the movement.

As part of putting our house in order, I had to consider the position of Ernie Ecob (1930-2000; NSW AWU Secretary, 1980-1993, Member of the Order of Australia from 1988), the honorary Labor Council president. He was a mostly decent union leader who, however, had a full deck of flaws – insecurities, paranoia, anti-Asian suspicions, misogynist attitudes.

Some might be tempted to say old-school AWU, except that is not how I found, say, Reg Mawbey (1927-2011), his predecessor as NSW AWU Secretary. Ecob’s gift for saying something excruciatingly memorable added to the drama of knowing him. Interestingly, Ecob’s most steadfast and articulate supporter was Marilyn Dodkin, his former secretary turned office manager, come Labor historian. To his credit, Ecob encouraged her to pursue university education. A son of a Baptist minister, Ecob never swore in her presence, she said. Dodkin saw him as a humble servant of the labour movement, personally generous, warm and courageous in the pursuit of justice. Yes, in some ways a throwback in some of his thinking, she advised me; but a man representative of a part of the labour movement’s base which is scorned at our peril.

In early 1989, Ecob publicly used a racist remark which prompted me to say to him privately, and later publicly, that he could resign or be sacked as President of the Labor Council of NSW. I was not sure if I could easily do the latter – as he had been elected to office. But he accepted my request. As he sometimes also made various patronising comments about women, I had to move him out. It was only ever a matter of time. But I created an indefatigable enemy who mattered later on. In the job I was in, you had to spend goodwill capital for the greater good.

There was a collaborative and productive spirit among those people who worked with me. One of the incidents referred to in the assessment of my secretaryship, to which this is a Postscript, is discussed by Keri Spooner in her review of the union movement in 1989 wherein she wrote:

Two officials of the Labor Council of New South Wales prepared a document concerning the role of unions, in which they expressed views contrary to the prevailing views of unions in 1989. The document was leaked, and a number of left unions, as part of a struggle to increase their representation on the Labor Council’s executive, voted for the dismissal of the two officials on the basis that they thought and wrote words contrary to prevailing union philosophy. There were two particularly interesting aspects of the incident. First, the Academic Association, a body usually at least officially committed to freedom of thought and expression, was signatory to the motion. Second, one of the officials was actually dismissed, which goes a long way toward supporting a theory that the fraternal bonding and loyalties which once held the Right together have passed with the changes in personalities. (‘Australian Trade Unionism in 1989’, Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 32, No. 1, March 1990, p. 142).

On the comradeship and loyalty point, the bonds were as strong as ever. Sadly, the official who was dismissed withheld from me and John Whelan, the Labor Council Vice President who conducted an investigation on the leak, that he had privately circulated the document to a former colleague (who gave it to Lindsay Fox, who sent it on in a chain to the Leader of the Opposition, Andrew Peacock, who then leaked the document “exclusively” to select print media in Sydney and Melbourne.) If I had of known that the discussion paper was shared with anyone outside of the office (something explicitly denied by the person in question), I would have devised a different strategy to deal with the matter. Whelan and I reported to a meeting of hundreds of delegates to the Council our initial findings, and now weeks later someone leaked in the media the way the document had come to light (which was the first I knew of that.) I had to act when I knew I was misled, and that truth was withheld. (The first I heard of how the paper leaked was in a newspaper report in the Sydney Morning Herald in December 1989. Someone was skiting.)

Union Amalgamation, Union Reform

Second, concerning the ACTU, I encouraged my deputy, Peter Sams, and Michael Costa, to speak their minds. With the support of Greg Sword, national secretary of the National Union of Workers (NUW), the old Storeman and Packers Union which, from 1989 following various amalgamations, became the NUW, I convened a meeting of unions concerned about union restructuring and mergers. We wanted case by case assessments. Some natural allies peeled away, with the ACTU offering to help facilitate favourable amalgamations for would-be dissenters. The national secretary of the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA) union, Steve Harrison (1953-2014), was one person who spoke out against the ACTU leadership changing the complexion of the movement. He came to see their merits, later. Who could blame him? Everyone had to reckon what was in their organisation’s and members’ best interest. In 1991, the FIA amalgamated with the Australasian Society of Engineers (ASE), who covered metal industry tradesmen, to form the Federation of Industrial, Manufacturing and Engineering Employees (FIMEE). A year later, the Australian Glassworkers Union and the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners amalgamated with FIMEE. The latter merged into the AWU in 1993. ACTU opposition could have stymied any one of those moves.

The Labor Council’s critique was that union amalgamations typically led to significant redundancy costs (as officials left or were retrenched), often led to significant membership loss (not everyone felt at home in a conglomerate union), and the combination of such pressures led to an inward focus, rather than innovation for survival.

Sadly, the AWU-FIMEE laboured under huge transaction costs of mergers (redundancies, primarily), loss of focus, financial strife caused by a rapid decline of metal manufacturing and the steel industry in the early 1990s, compounded by an economic recession. There were years of leadership turmoil, resignations, and sometimes sackings. One result was a significant loss of members, fewer people to fight the battles, fewer resources to service members.

In many workforces, though not all, there were too many unions fighting over membership, sometimes causing industrial disputes. This was mainly concentrated in the building and manufacturing industries — the latter a rapidly shrinking part of the workforce.

Sitting on top of an anvil bench was not the perfect perspective for every industry. The Labor Council officers queried whether in some sectors significant membership loss would occur with bigger-is-better amalgamations. As Patricia Staunton, head of the NSW Nurses Association, once said to ACTU secretary Bill Kelty that not everyone is thrilled to be a member of conglomerate union No. 8. They liked their industry identity such as nurses do. What mattered most with individual unions was service, effective management, and value-for-money for members and potential members.

The Labor Council was ineffective, except at the margins, in running this critique. In 1993, I objected to the proposal in a draft Industrial Relations Reform Bill, proposed by the Minister Laurie Brereton, that unions smaller than 15,000 members be de-registered or forcibly amalgamated. In part, my argument was that this proposal would be a breach of ILO Convention 87. Articles 2, 3, and 4 of that convention clearly prohibited the government’s proposal. The relevant articles from that Convention read:

Article 2:

Workers and employers, without distinction whatsoever, shall have the right to establish and, subject only to the rules of the organisation concerned, to join organisations of their own choosing without previous authorisation.

Article 3:

1. Workers’ and employers’ organisations shall have the right to draw up their constitutions and rules, to elect their representatives in full freedom, to organise their administration and activities and to formulate their programmes.

2. The public authorities shall refrain from any interference which would restrict this right or impede the lawful exercise thereof.

Article 4:

Workers’ and employers’ organisations shall not be liable to be dissolved or suspended by administrative authority.

Given that the government claimed that ratified ILO Conventions provided new heads of power in the corporations, industrial relations, and related areas of the law, it seemed reasonable to stick to the Conventions. Cancelling union registrations defied the right of workers to join any organisation of their choice. I knew the government’s move was a ruse to demoralise some smaller unions to give up fighting for their independence. The legislation, ultimately, dropped that provision. Before that happened, I decided at a meeting of ACTU representatives to vote against the draft Bill in its entirety because of that proposal. It annoyed the ACTU leadership that I did so. The mindset was that it was ‘obvious’ and ‘necessary’ to force through amalgamations. For some minds made up, nuanced, case-by-case analysis can look too ‘academic’.

Declining Membership

On the matter of weakening union density numbers, the third point above, I thought we could address this challenge by extending union services and representation. Many of the Chapters in the book I edited with Michael Crosby, What Should Unions Do? (Lloyd Ross Forum/Pluto Press, 1992) addressed those issues. Naively, I had hoped that Chifley Financial Services, might also be a reason to join unions. Good services were provided by Chifley, but it was not the big game-changer that I had hoped for.

I came to believe that union fees were a problem and something along the lines of associate membership (or gradations in fee levels) needed exploring. Calling someone an “associate member”, however, might imply that they were less than a full member and in a second-class category. The marketing needed careful calibration. Indeed, none of my Labor Council team thought “associate membership” called as such would be appealing. The basic issue was “what should unions do”?

My conclusion was that the individual unions needed to tailor their policies and organising activity to their industry(ies) and make the right calls on how to win over and represent members. The Labor Council role, besides the actions we took in the industrial relations process, on behalf of and in consultation with affiliates, was to be a clearing house, a forum, for fresh ideas and sharing of experiences.

Financial Advice and Super

On the fourth challenge in 1988, as assistant secretary, I had another go at forming a public-offer superannuation scheme, Asset Super, as described in ‘The Secretaryship of Michael Easson’ article above. In 1989, as Labor Council secretary, I also looked at financial planning and advice, forming Chifley Financial Services (CFS), and later a Chifley trustee entity. CFS was formed with Brian Sherman’s and Laurence Freedman’s Equitilink company as a 50/50 JV. (I wanted entrepreneurs to be Labor Council’s business partners. These two South African migrants had built something from scratch.) David Goss, a brilliant marketing mind and driven entrepreneur, was appointed the initial CEO. I seconded Michael Costa to work with Goss over the first six months and then part-time in developing the business. As members of an independent advisory board, I appointed Jim Dominguez, a former investment banker, Gerry Gleeson (1928-2017), the former head of the NSW Premier’s Department, and Dick Warburton, the former head of DuPont Australia, which had an exceptional reputation in occupational health and safety and good management. I wanted their commercial and ethical oversight on anything we proposed in the area of financial advice and services.

Getting Heard

Fifth, the distinctive voice of the Labor Council needed new outlets. In 1990, the Lloyd Ross Forum was formed to air issues for discussion, publish research papers and books. Various publications were issued on topics ranging from industrial relations reform, to immigration, to industry policy, to a focus on modern unionism and new growth strategies. From across the broad ALP-aligned sections of the labour movement, the inaugural members of the Forum’s executive were: Jim Macken (1927-2019), Chair, former judge of the Industrial Commission of NSW; Patricia Staunton, NSW Nurses; Michael Crosby, Actors’ Equity; Steve Harrison, FIA; Liz Bishop, Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union: Professor David Plowman (1942-2013), University of NSW; Jeff Shaw QC MP (1949-2010); Michael Costa; and myself as Forum secretary.

I hired Social Change Media (as Ric Sisson’s company was then known) to help improve the Council’s image, the production of advertisements, and campaign material. Labor Forum and Labor Network journals were issued on thought issues and industrial campaigns generally.

The Recession

On the sixth point, the unfolding economic downturn was devastating. The Australian economic recession of 1990-91 saw a significant slump in employment (of around 4%) and sharp rises in unemployment (around a 5% rise to 11.2%). The recession was severe in terms of mass job losses, corporate collapses, and financial failures. Variable mortgage rates were 17 per cent, with consequential economic and social damage. This had profound effects, not all of which were fully appreciated at the time. Manufacturing industry significantly shrank. Union membership and union density diminished. The Labor Council which had nearly 1,000,000 members from affiliates in the early 1980s, lost 200,000 members by the early 1990s. That meant considerably lower capitation fee income. I cannot remember the per capita member formula ($1.80 per member?), but the financial impact was severe.

With the economic downturn in the early 1990s, all I could do was cut back on our expenditure to better match our income, better manage 2KY’s finances, and look to investing some funds in an asset that might provide an income and potentially grow in value.

Finances