Profile of Michael Easson by Tony Stephens, Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday, 15 July 1989, p. 73.

Books mirror the soul of their readers. In order to understand what drives a particular person, it can be instructive to know which books he or she reads. Which writer is now being read by the leader of the trade union movement in NSW?

“Alasdair MacIntyre,” he says. Alasdair MacIntyre?

‘”He’s a leading ethical philosopher.” Ah, ethical philosopher.

MacIntyre is a Briton living in the United States who moved from Augustinian Christianity to being a Marxist, then a Trotskyist, before turning to Catholicism. He has written such tomes as Against the Self-images of the Age, The Religious Significance of Atheism and After Virtue, A Study of Moral Theory. In the latter, published in 1981, MacIntyre concluded: “What matters is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time, however, the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers, they have already been governing us for quite some time.”

The union boss is currently reading MacIntyre’s latest work, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? It is one of 6000 books, plus historical documents and pamphlets, Michael Easson has in home. His elder daughter, 3.5-old Louise, is already talking about where she will put her library.

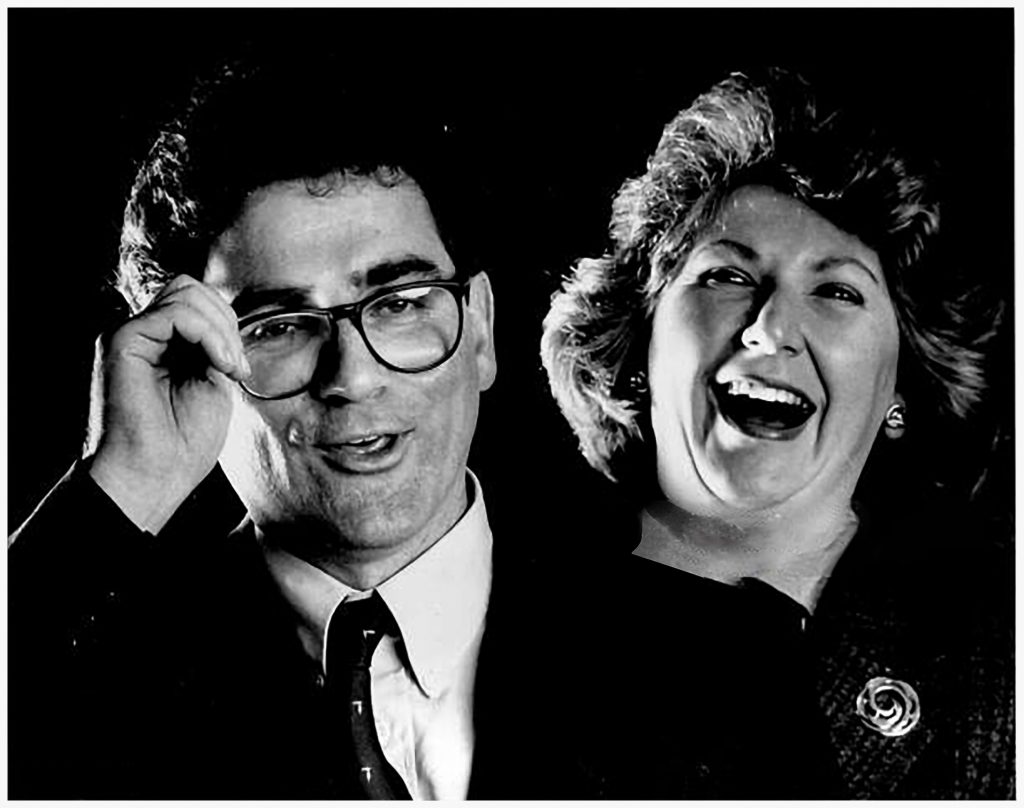

As secretary of the NSW Labor Council, Easson is leading what some people see as the greening of that organisation, a council traditionally led by electricians and boilermakers, battlers for their worker mates. Barrie Unsworth and John MacBean were the last of a century-long line of blue-collar leaders. Easson is more like Bob Hawke, Bill Kelty and Simon Crean, more like them, though not much like them.

The so-called greening of the Labor Council would be more accurately described as a multi-colouring. This provides for a rich mix of talent based primarily on education and diversity. The mixture is pushing the labour movement upwards and outwards from its previously narrow, blue-collar base.

Neville Wran did it for Labor in Macquarie Street, where Bob Carr is continuing that process, after a period in which Barrie Unsworth tried to take it back to basics. Gough Whitlam did it before for Labor in Canberra. Bob Hawke’s Cabinet is probably better educated than Andrew Peacock’s shadow. Cabinet and is certainly more diverse in its social background.

In Sussex Street, the multi-colouring is even more marked. This is partly because it is the last bastion of old-style Labor. Whitlam’s Labor started taking on a richer fabric 20 years ago. Wran’s Labor about 15 years’ ago. Michael Easson took over from John MacBean only this February.

There is another dimension to the multi-colouring. Easson’s deputy, assistant secretary Peter Sams, has a diploma in music from the Conservatorium of Music. He plays the cello. He also surfs and grows flowers – snapdragons and nemesias will shoot from his front garden this spring.

Beryl Ashe is the council’s first female organiser. She is now in the Soviet Union on an ACTU course. Michael Costa is sometimes called the council’s first ethnic organiser. The other organiser, Mark Lennon, is a bachelor of commerce studying law whose other interests include help for undeveloped nations, debating and music. When Lennon visited the strikers at Cockatoo Island – Easson fondly calls them “the Cockatoo Soviet” – Easson suggested: “Try the Leninist approach.” Not too many people got the joke.

Lennon, Costa, Sams and Easson are all aged between 30 and 34. They sometimes call Ashe, a decade or so older, “mother superior”.

Easson is sometimes defensive about his academic inclinations and love of philosophy. He says: “I am not at home with academics. I am at home with the trade union people I represent.”

This defense was sparked by attacks on him before and immediately after his appointment to succeed MacBean. The attacks came from grassroots sections of the labour movement suspicious of his lack of shop floor experience. They have stalled in recent months but will be heard again if he is not seen to ‘perform’ in the current confrontation with the NSW government.

Easson, again defensively, points to his working-class background. It has been reported that his grandfather, a Scot, did not attend school at all. In fact, he went to school until sailing to Australia on a merchant ship at the age of 12. Although it might have been inadequate, he received a merchant navy education. Easson’s mother and father both left school in their second year of high school, to go to work. Both resumed their education later, the father becoming a bank manager and mother a clerk, with some accountancy qualifications.

Michael Easson’s earliest political memory is of his mother crying over the death of John F. Kennedy. Young Easson was eight, growing up in Peakhurst and attending school at Marist Brothers, Penshurst. With his twin brother, Shane, he went on to Sydney Technical High School. Both joined the Labor Party at 18.

The twins share a hearing problem, a defect in the auditory nerve. It means they cannot hear whispered or high pitch sounds. They sometimes have difficulty on a telephone and in distinguishing sounds in a crowded room. Hearing aids do not help because they amplify all sounds. Michael often resorts to lip-reading. He has a minor, associated speech defect, which emerges as a lisp. Despite the difficulty, he would like to learn another language.

By the time Easson was 13, Bobby Kennedy had become a political hero. In 1972, he was caught up in the excitement of Whitlam’s “It’s Time” campaign, taking the odd day off school to satisfy his political taste buds.

He discovered another passion on one such day. Bob Rogers, the radio personality, played a recording by jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, ‘The Feeling’s Good’. Easson immediately went out and bought the record. He rates Vaughan the world’s best female singer. He also thrills to Chet Baker and the Australian Vince Jones. Easson has another passion, for old black-and-white movies. He is very fond of ‘Follow the Fleet’, with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, but his favourite is ‘The Third Man’, from the Graham Greene novel. When he and his wife, Mary, came home from their honeymoon at the end of 1984, Michael looked up the WEA film program, noticed The Third Man was being screened, and drove into the city to see it. Mary Easson, “too tired”, stayed at home.

Whitlam was “a great hero” for the growing Easson. “He was a brilliant failure,” Easson says now. “Graham Freudenberg got it right when he wrote of Whitlam’s ‘certain grandeur’. He changed the Labor Party, did an enormous amount for the country and opened up Australia. He was a great inspiration, a reminder of the magic of politics. He was, however, weak in economics.”

In 1976, a year after the then Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the elected Whitlam government, Easson graduated with first-class honours in political science from the University of NSW. His main interest was philosophy. “If I’d had the money” he says, “I would have gone overseas for post-graduate studies.” He completed one year of a degree before taking a job. “I would save a bit of money and go back to academic life. I lacked the confidence to become an academic straight away. Taking a job was appropriate to my personal development at the time.”

A clue to Easson’s dichotomy of interests is found in the man from the Australian union movement who has inspired him most, Lloyd Ross. Easson, who has completed the research for a biography of Ross, used to take tea occasionally with Ross. When the latter died in 1987, aged 86, Easson was attending the ACTU Congress in Melbourne. While Prime Minister Hawke addressed the congress, Easson wrote an obituary, subsequently published in Quadrant: “In many ways Lloyd Ross was the odd man out. In the Australian trade union movement he was the first and only man to hold a doctorate of letters and a leading position in a blue-collar union. In the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom, he was a strong Labor man…” Ross was secretary of the Australian Railways Union from 1935 to 1943, when he joined Ben Chifley, ultimately working in the Post-war Reconstruction Department. He had a year as an industrial journalist with The Herald in Melbourne, applied for the job as Professor of Political Science at the ANU, only to be beaten by Chifley’s biographer, Fin Crisp, returned to the ARU and wrote a biography of Chifley’s predecessor, John Curtin.

Easson’s obituary says Ross’s books and articles made significant contributions to labour history. Ross “played a significant role in articulating a liberal and democratic socialist alternative to the sillier ideas of Left and Right”. He “contributed mightily” to the anti-communist cause after resigning from the Communist Party of Australia in 1941. He “did some magnificent things for rail workers”, did much to improve the dignity of labour and was one of many in the labour movement to perform the role of civilising capitalism.

“Ross was interested in ideas in education and tolerance,” says Easson. He believed in the powers of conversion and persuasion. He was so consumed by unionism that he did not do the work he was capable of. His talent was wasted in some ways. A different occupation might have given him more time for intellectual activities and writing and Australia would have been the richer for this.”

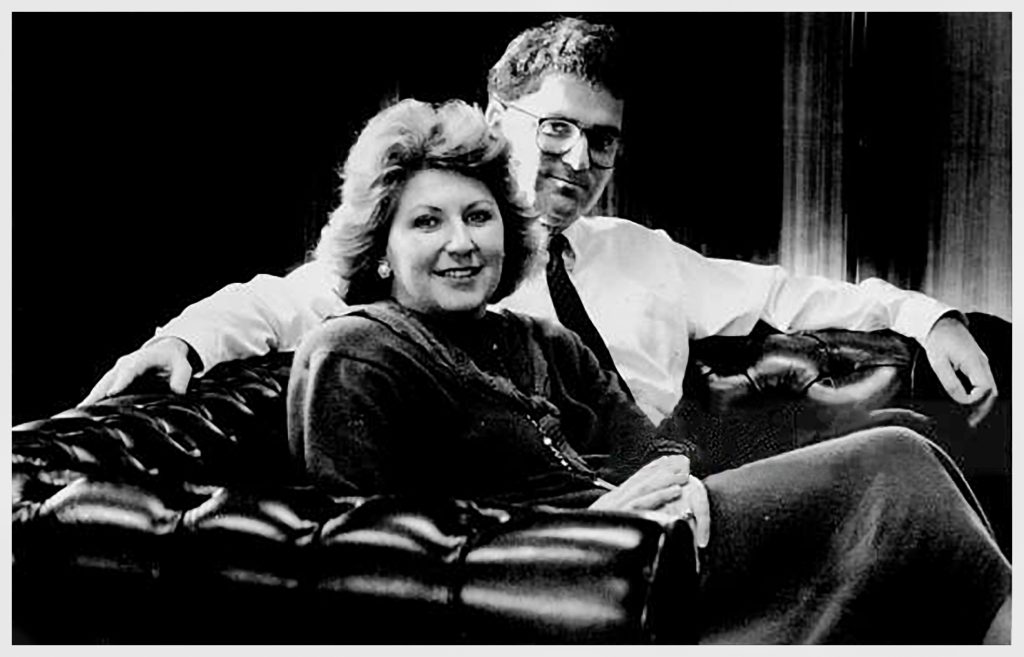

Easson’s wife has been a more recent influence. At 20, Mary was the first female president of young labor in Victoria. They met at Labor conferences where each considered the other as a vote. “It was after he defected (from the Left),” she says. He explains: “I joined the left because most of my friends were aligned with the Left. I was there only a year.’’ Bob Carr claims the credit for dragging him “across the Berlin Wall.”

Mary Easson says Michael and Shane argued vigorously after Michael’s defection. Shane, who has also worked with the labour movement, is now studying for an MBA at the University of NSW. His wife, Catherine, was Mary Easson’s best friend. Mary Easson won Labor pre-selection in April for the Federal seat of Lowe, now held narrowly by Liberal Dr Robert Woods. The Eassons had wanted John McCarthy QC to stand. Easson sometimes rings McCarthy for literary or historical allusions. It was McCarthy who pointed out that Romans appointed to the Senate before their 35th birthdays – like Nero and Caligula – tended to go mad. In any case, McCarthy did not want to contest Lowe. Michael Maher, who lost the seat to Woods, urged Mary Easson to stand.

Mary says she tends to use the force of her personality, Michael the force of argument. She is more pragmatic, he more ideological. She is more of a backroom person, he more upfront on policy.

Politics, including the politics of the union movement, is a way of life for them. Mary Easson says the worst thing happen to their children – Louise and Amanda, who is just under 12 months old – would be for them to be apolitical.

Michael Easson changes nappies and reads to his children. Although he says he is not as modern a father as some, he is more modern than most old union leaders. He says: “It’s very therapeutic for people in positions like mine to come home and be told by your three-year-old, ‘Daddy, you be Peter Pan and I’ll be Wendy’.”

They live in Ashfield and attend the local Catholic church. He earns $60,000 a year and their combined incomes put them in the higher incomes bracket. Yet Easson says he would never move to Turramurra, as Unsworth and MacBean did. He believes part of the Greiner government’s problems stem from the fact that so many members live on the North Shore.

There are plenty of recent precedents to suggest that Easson will move from unionism and its related politics to the more concentrated politics of parliament – Hawke, Unsworth, Carr, Simon Crean. Easson says, however: “I don’t want to become a political kleptomaniac.” He believes he can achieve more as a union officer, where life is more exciting and where time is not wasted by such necessarily political functions as fetes.

He gives himself 10 years in his current job and would then consider a position as a union’s Federal secretary something in international relations or in academe.

Easson respects NSW Premier Nick Greiner as a business manager but does not believe he can manage people. He points to the broken promises over Tallawarra power station, Huntley colliery and the Government Printing Office and the decision, later changed, to levy everyone, including pensioners in the Blue Mountains, $80 to clean up Sydney’s sewage problems. On the other hand, he has a “reasonable working relationship” with Industrial Relations Minister John Fahey.

Easson’s short-term challenge is to meet Greiner’s hard-nosed business decisions. Elcom workers struck on Tuesday and July 25 has been marked by the Labor Council as a ‘day of outrage’ which will include a 24-hour State-wide public sector strike. The overwhelming majority enjoyed by Easson’s right wing in the council was eroded when union anger forced the strike decision. Peter Sams says: “The strike will be a focal point for the community against the government’s manic obsession with winding back the public sector and destroying jobs.”

Easson’s longer-term challenge is to make the Labor Council more relevant to workers at large. Trade union membership has declined from 51 per cent of the workforce in 1976 to 42 per cent. Less than one-third of workers in the private sector belong to unions. “The big issue is to market ourselves and to recruit,” he says. “The union movement has forgotten about the techniques of organising. We have a much more skeptical workforce.”

Easson returns continually to the theme of civilising capitalism. He sees wages policy as an instrument for changes in productivity and training, so that workers can realise their full potential. “Surveys show that job satisfaction is the most important factor for workers.”

Employers, says Easson, have not been nearly as innovative as unions in bringing such change. “The humane and the economic approaches need not be incompatible,” he says. He also believes companies have been slow to seize export opportunities, a subject on which Easson offers lateral thoughts. A member of the Australian Manufacturing Council, he says Australia could add billions of dollars to export income by treating and degreasing wool before selling it. Spinning he wool would add furher billions. “We could have a joint venture with Ermenegido Zegna (the Italian designer whose suits are worn by Treasurer Paul Keating),” he says, only half joking. “We should be selling such goods as woollen carpets and furniture to the middle classes of India and Indonesia. Which offer larger markets than Australia.”

Easson questions the slavish following of free-market policies, doubts shared by some economic opinion leaders now expressing their reservations about deregulated dollars and deregulated trade. “We shouldn’t worship the markets,” he says. “They ought not to be the sole factor. Deregulation has not encouraged companies to expand to cater for the needs of industry. BHP did not expand to provide for needs. We now import steel.”

He is a pragmatist, “if one means tempering one’s ideas”. He adds, however, “I am not an ideological atheist. I believe in a social democrat approach to the world.”

His philosophy is not that the Labor Council be a tool to get more from the system but that it “should civilise capitalism and moderate the excesses of the employers on society. It should exemplify some of the good things in society and be a clearing house for ideas. It should be a tug of reality away from more doctrinaire ideas and towards the disadvantaged. The cause of encouraging greater discussion and democracy will never end.”

That is why Michael Easson, like Bob Hawke, wept over the students in Tiananmen Square. “To have a leader who weeps for humanity and who feels for the people of China made me proud,” he says.

Wasn’t it a fact that Australians could do next to nothing about China? “It’s a test of our humanity,” he says before recounting a Chinese fable told by 17th century scholar Zhu Liang-Gong: “A flock of doves lived in the forest until, one day, it was ravaged by fire. The doves flew repeatedly to a creek, dipped their wings in the water and flew back to the forest, shaking their wings over the flames. God said to the doves, ‘Your intentions are excellent but don’t you realise that what you do is of no prac1ical consequence?’ The doves replied: ‘we understand, but we lived in the forest and what we see breaks our hearts’.”

That sent me back to Alasdair MacIntyre’s Whose Justice? Which Rationality? “… our society is not one of consensus but of division and conflict, at least so far as the nature of justice is concerned… For what many of us are educated into is not a coherent way of thinking and judging, but one constructed out of an amalgamation of social and cultural fragments inherited both from different traditions from which our culture was originally derived (Puritan, Catholic, Jewish) and from different stages and aspects development of modernity (French Enlightenment, Scottish Enlightenment, 19th century political liberalism, 20th century political liberalism). How ought we decide among the claims of rival and incompatible accounts of justice competing for our moral, social and political allegiance? Under the Enlightenment, it was hoped reason would displace authority and tradition…”

Friends call Easson charming; opponents say he is unpleasant. Some people wonder whether the philosopher will have the stomach for the struggles ahead. “The biggest compliment anyone can pay me is to underestimate me,” he says.

Postscript (2017)

This was a magnificent and humbling profile by one of the Sydney Morning Herald’s best biographical portraitists. But it stirred resentment and hostility in a minority of union leaders. For example, Ernie Ecob the NSW AWU Secretary, 1980-1993, was one fierce critic. I had forced him to resign as President of the Labor Council of NSW in early 1989.

Ecob argued in the ranks that the Stephens article proved I was a weird boffin, far from understanding working people. This criticism stirred me to be more involved in industrial relations matters, campaigns and associated strategy at the Labor Council.

Sometimes critics can help you focus better without being less authentic in the process.

The quote from Zhu Liang-Gong I found in Simon Leys’ (the pseudonym for Pierre Ryckmans’) book The Burning Forest (1983). In 1989 I quoted those lines at the June 1989 NSW ALP Conference in speaking to an Urgency Motion on the Tiananmen Square massacres.