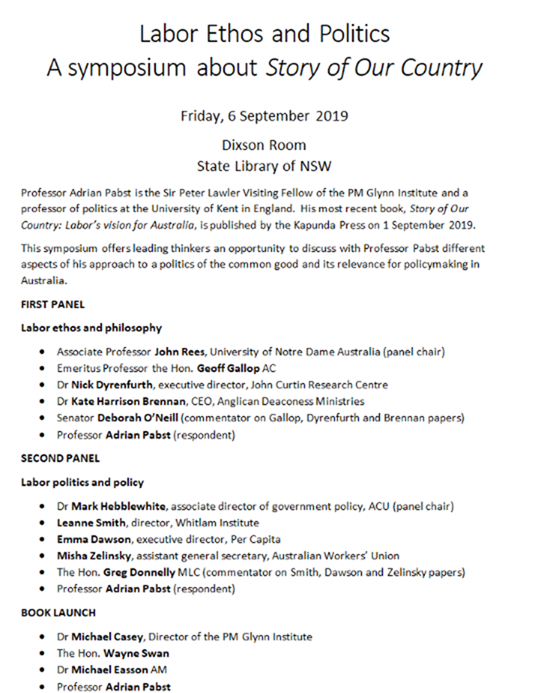

Notes of a speech delivered at a book launch at a symposium on ‘Labor Ethos and Politics’ inspired by Adrian Pabst’s book Story of Our Country (2019) in the Dixson Room, State Library of NSW on Friday 6 September 2019.

I will try to be brief, as the main event lies ahead: hearing from Adrian Pabst and queuing for his signature on a copy of the book.

I want to speak about values, traditions, and the local.

Values and NSW Labor are two terms that create a chuckle in some circles – especially over the past fortnight: ICAC and all that.

Everyone I know in politics starts as an idealist – a person interested in translating ideals into practice.

The beginning of the Australian labour movement lay in moral indignation. Labor was put on this earth to enable the full realisation of the potential of every one of us. Because human beings are human beings, serious injustice to any person is an outrage.

Improving the lives of our people is a sacred duty.

This is very much the story of our country, to allude to the title of Adrian’s book.

Labor sees ideas about liberty, fairness, loyalty, authority, sanctity as encapsulated in the phrase “a fair go.” William Lane in his Workingman’s Paradise (1892) wrote: “To understand Socialism is to endeavour to lend a better life.” To do that requires living by certain values.

Tradition involves reckoning and appreciating as well as developing the best of our history. That is a constant task of renovation and improvement, rather than starting out new.

This is the merit of Pabst’s book. He presents and analyses important parts of our history. He wants solutions for our times developed consistent with our creative imagination and mindful of our story.

Labor is not like any other party.

A couple of years ago, at his tribute dinner in June 2017, the great Labor speech-writer, guardian and espouser of our traditions, Graham Freudenberg – who died recently – said: “For the Labor Party, our history is an even more important source of our sense of identity and belonging than policies. We are custodians… but we cannot protect them properly without understanding their history.” Nor can we nurture and draw on the traditions of our movement as we innovate further unless we understand our past.

In this context, it is significant to see in this book references to Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish philosopher, politician, and statesman who is best remembered for his defence of liberty, his defence of human dignity, his opposition to the madness of the French Revolution.

Freudenberg told me that he read Burke as a teenager. In his memoir A Figure of Speech (2006) he says: “The Burke I loved was the defender of party, the champion of American independence and the prophet of toleration in Ireland and human rights in India.” And argues: “The American neo-conservatives who today claim Burke for their own have obviously never read him.” That last statement serves to emphasise Burke was no stuffy conservative, even if nowadays the other side of politics are apt to claim him as their patron saint. Freudy, as friends called him, wrote:

Being both sentimental and superstitious, I have carried my battered copy of Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France on every journey overseas since 1956… There was a time, at my most pretentious, when I thought I might be able to introduce the cadences of Edmund Burke into Australian oratory; in the end I had to settle for echoes of Tony Blair. As Burke said, ‘Oh! What a revolution! And what a heart must I have to contemplate without emotion that elevation and that fall!’

Freudy threaded into Arthur Calwell’s book Labor’s Role in Modern Society (1962) parts of Burke’s thinking, including passages from Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770) in defence of party politics.

Pabst might be said also to infuse his book with Burkean ideas, themes and perspectives. In doing so he clarifies “…the question of Labor’s animating energy and ethical outlook.” And in dealing with the Judeo-Christian inspiration of most of the early leaders of Australian Labor, he sees that “Catholic social thinking… offer some rich resources for radical reform and policy ideas.” Of other traditions, Christian and non-Christian, he urges Labor to reconnect with our heritage, to engage with various faiths and their adherents, as a source of renewal and conversation.

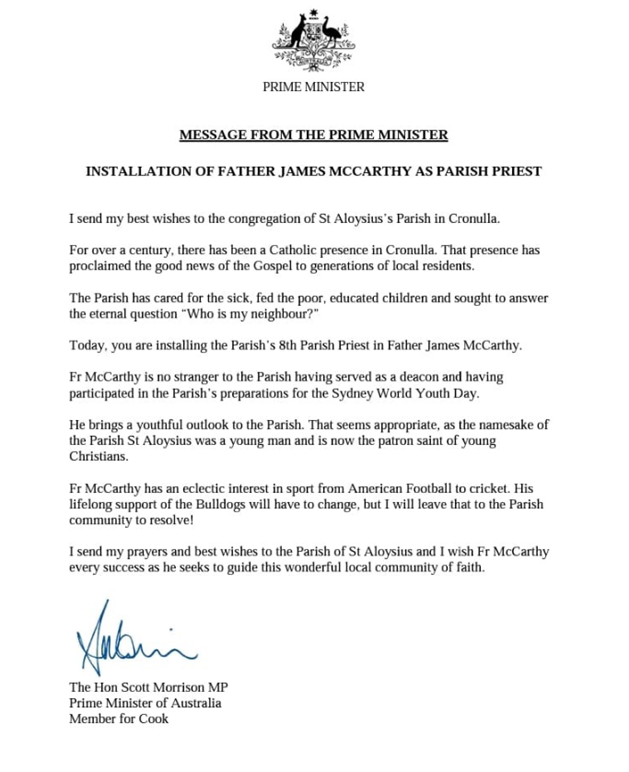

I want to now reflect on the local by reference to a letter from a Federal MP, that is instructive, that I recently saw on the instalment in a particular parish of a new priest, someone I know who comes from a Labor family.

Some excerpts from the letter of welcome are worth quoting:

“I send my best wishes to the congregation…

“For over a century, there has been a Catholic presence [here]. That presence has proclaimed the good news of the Gospel to generations of local residents.

“Today, you are installing the Parish’s 8th Parish Priest in Father James McCarthy.

“Fr McCarthy is no stranger to the Parish having served as a deacon and having participated in the Parish’s preparations for the Sydney World Youth Day.

…

“Fr McCarthy has an eclectic interest in sport from American Football to cricket. His lifelong support of the Bulldogs will have to change, but I will leave that to the Parish community to resolve!

“I send my prayers and best wishes to the Parish of St Aloysius and I wish Fr McCarthy every success as he seeks to guide this wonderful local community of faith.”

Those quotes are from the Federal MP for Cook, the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison.

When our local members can communicate like this – knowledgeably, empathetically, with humour and confidence – I know then that we are on the right track.

With this single example, I see how far we need to go – and why the themes of this book need to be understood and acted on.

Postscript (2020)

At the launch, after the former Treasurer and ALP President Wayne Swan spoke for a lengthy period defending his record and Labor’s policy positions at the previous Federal election, I lost heart about delivering my full speech. Swan ignored most of Pabst’s book and used the presence of the word ‘jobs’ as a pretext for intervening in the election post-mortem. He was keen for the audience to understand that the only mistakes made were tactical (i.e., not by me, who will be vindicated by history).

It was such a “packed” afternoon: with contributions from Professor Adrian Pabst, the Sir Peter Lawler Visiting Fellow of the PM Glynn Institute and a professor of politics at the University of Kent in England; Associate Professor John Rees, University of Notre Dame Australia; Emeritus Professor the Hon. Geoff Gallop AC; Dr Nick Dyrenfurth, executive director, John Curtin Research Centre; Dr Kate Harrison Brennan, CEO, Anglican Deaconess Ministries; Labor Senator Deborah O’Neill; Dr Mark Hebblewhite, associate director of government policy, ACU; Leanne Smith, director, Whitlam Institute; Emma Dawson, executive director, Per Capita; and Misha Zelinsky, assistant general secretary, Australian Workers’ Union, as well as questions from the floor.

Barrie Unsworth told me at the break before the book launch at 5.45pm that it was a long day already and that he would be heading to Mona Vale. An audience of around 20, standing up, remained.