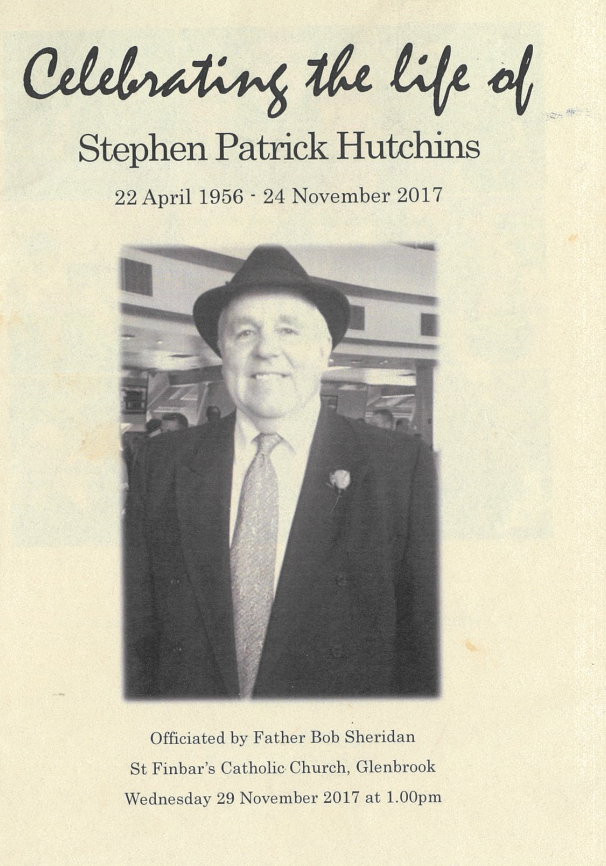

Published under the heading “Obituary: Steve Hutchins – From Garbo to Senator” in The Tocsin, Newsletter of the John Curtin Research Centre, Issue 4, March 2018, pp. 27-29, https://www.curtinrc.org/publications.

Stephen Patrick Hutchins (22 April 1956 – 24 November 2017), “Steve”, “Hutch” or “Hutcho” to family and friends, former Labor Senator and transport union leader, hard-nosed factional warrior, in many ways typified the old NSW ALP right – tribal, loyal, fierce in response to social injustice, fully aware of the traditions of a minority within the broader national ALP, and with a great sense of humour.

Hutch was a person most Labor people assumed would become a senior minister in a Labor government when, at age 42 in 1998 he became a Senator representing NSW; he never fulfilled his potential due to the frustration of debilitating illness which dogged him for 20 years.

He was born in Sydney and grew up in Cronulla, in the Sutherland Shire in Sydney’s south, to Peter, labourer and itinerant worker, and Patricia (“Pat”), clerk and domestic worker, now both deceased. Life was tough and impoverished for Steve and his younger sister Linda; their parents separated; sadly, there were prolonged absences from his father who did time in prison for various crimes.

Steve attended De La Salle College, Cronulla and Sutherland, packed liked sardines in over-crowded classes. Lifelong friendships were formed. Michael Lee recalled at his funeral: “in those days students swept their own classrooms. In that first school week in 1969, I dropped a desk on his foot. In 2011 in his final speech to the Senate he said he forgave me, 42 years later…” His children were variously told that the mangled toe was a result of a shark bite or a crocodile attack. Their dad was a prankster at heart.

At the funeral on 29 November last, Lauren Hutchins, the eldest of Hutchins six children, spoke about how her father played the part of two fairies at home when she and her siblings were young. Signing off as “Portia” or “Cressida”, he would leave notes hidden in the backyard for the children to find. His love of family was the warm, softer side of a man who often seemed so tough. He often proudly spoke of his kids.

Sometimes careers and commitments can turn on chance events. When he was Education Officer of the Labor Council of NSW in the early ’70s, Bob Carr travelled the city speaking to school History classes on the labour movement; he spoke at Steve’s school and so inspired them that Michael Lee, Hutcho, John Della Bosca, Seumas Dawes – together, a future Labor Minister in the Keating government; a future Labor senator; a NSW Secretary of the ALP and senior NSW minister; a future NSW ALP Assistant Secretary and investment wunderkind – all joined from that class and immediately started campaigning for Gough Whitlam and the overturning of 23 years of conservative government.

Hutcho went on to study for an Arts degree at the University of Sydney, majoring in English. His education in Labor politics was also proceeding apace. In the Cronulla branch of the Labor Party, an island of the Right in the generally left Shire, the late John Russell, intellectual and former seminarian, was an early inspiration, as was the future NSW Treasurer, Mike Egan. Like anyone making their way in the movement, he fought to find his place, learnt to think about his point of view as he developed perspective and his own contribution.

At Young Labor conferences, the right returned in 1975 to the fray after two years’ absence, the left in complete ascendancy. Hutcho was the leader of the callow youths trying to turn back that control. Unlike the ALP in other states, the NSW Left was then an amalgam of the sensible Ferguson faction – named after former NSW ALP Deputy Premier Jack Ferguson (1924-2002), and the harder line, pro-Marxist Gietzelt group. In Young Labor, the most formidable of the Fergusonites was John Faulkner, another future Senator, who would regularly excoriate some outlandish breach of the rules allegedly perpetuated by Head Office, dominated by the Right. Hutcho, bravely, usually taken by surprise and unaware of all the facts, would do what he could, trying to change the topic, debate something else, inspire his colleagues that there was something noble in the struggle. It was great theatre, but mostly as you now look back, this was the honing of great oratorical skills in a policy formation hothouse. In the days when the ALP factions were democratic at their nursery stage, all kinds of issues were debated. The Young Labor groupings mostly selected their own leaders (rather than handpicked from above) and deep friendships were formed, including across the factional divide.

Then NSW ALP Assistant Secretary, Leo McLeay, came to know of Hutcho and urged him to think of a union career. He introduced him to Ted McBeatty, bachelor, Catholic daily communicant, humble, but also a tough man as Secretary and head of the NSW Transport Workers Union. Ted was one of those who, in the midst of the ALP split in 1956, wrested the union off the Left just when the ALP Right was most in danger; the TWU provided the clinching numbers for moderate Labor in NSW.

Hutch was urged to get a real job and join the union; he did so, working as a forklift driver and then as a garbage collector, falling off a truck in his first week – breaking his arm – and resting on “compo” for a few months; then went back to work, gripping harder on the trucks. Finally in 1980 he was appointed as an Acting Organiser in the union. McBeatty became a father figure. Hutch quoted him as saying “graveyards are full of people who thought they were indispensible.” An avid fisherman, McBeatty drowned in a boating accident in 1983 and was succeeded by Harry Quinn, a colourful, militant leader, with whom Steve did not enjoy the closest of friendships. The union came first and Steve did the rounds, visiting workplaces, up at the crack of dawn, campaigning, listening, representing, the stuff of union organisers. He was deeply proud that battles fought depot by depot in NSW set the pace for conditions for transport workers in the rest of the country.

In NSW the TWU was particularly effective because of its wide reach, including representing owner-drivers, assisted by a 1969 NSW legal case, known as Moore V. Doyle, which established the right of the union to represent them.

By the eighties and married, Steve and his then wife Diane Beamer bought a home in Penrith for their rapidly growing family.

He was selected to attend the 1984 Harvard Trade Union Program, that “Swiss finishing school for union officials”, as Barrie Unsworth once quipped. Don Farrell, now Senator and Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, also went that year and noted: “At Harvard, Steve saw first-hand in American industrial relations what would later become Work Choices under the Howard government in Australia.”

Over there and on his return, Steve had his moments wondering about the future. There were some dark nights of the soul.

In 1989 with the retirement of Quinn, a new leadership was proposed by the outgoing Secretary, which tilted more left than right. Steve saw this as an existential threat to the traditions of the union and all that he had learnt from Ted. So he organised a rival ticket and they won. John McLean was elected NSW TWU Secretary, with Steve elected as his assistant. Steve brought in Tony Sheldon, now the National Secretary of the union, as someone for the longer term to carry on the legacy. In 1994 Hutchins succeeded as NSW Secretary, serving to 1998, and as honorary federal president of the union in the same period. He was an ACTU Executive member from 1996 to 1998. Other positions held were as Senior Vice-President, ALP (NSW) 1995-98; President, ALP (NSW) 1998-2002; member, ALP National Executive 1997-2002, National Vice-President, ALP 2000-02. Over the years 1995-98, when he was Secretary, the TWU along with the NSW Nurses Association was one of the few NSW unions to increase membership each year.

Hutch was not a fan of national mega unions. He foresaw that the slew of reforms aggressively pursued by the ACTU and the Keating government would weaken the state system of industrial relations. He derided the potential impact as severely weakening the union movement’s reach into workplaces, potentially creating bureaucratic conglomerate unions.

Steve played a pivotal role in getting the Labor Council of NSW to warn of the dangers; he led opposition to simply replacing National Wage cases with enterprise bargaining because he believed low paid transport workers could be worse off. He argued that the destruction of the NSW state system would hurt the union movement as a whole.

In 1996, defying ACTU counsel, Steve led the campaign for a 15% increase in the state transport award – which the NSW Industrial Commission awarded in December that year.

His toughness in this time was legendary; derided in Melbourne as a dinosaur, some of his fears can now be more sympathetically examined. He was known as a resolute man balanced by compassion and integrity. Employers knew after any stoush that his handshake was his word. He was trusted to deliver.

In October 1998, Steve was appointed to fill a casual vacancy in the Senate and was elected in his own right the same year and re-elected in 2004. His term came to an end after the 2010 election when he was defeated in the Gillard election, third on the ticket. He was critical of some of the excesses of the NSW powerbrokers and thought they were destructive to good management of the political process. He went to Melbourne to live, supporting his wife, Natalie, whom he was to be with for 18 years.

In his first speech as a Senator, he spoke passionately about those Australians left behind by the pace of economic reform. As a Senator he chaired inquiries into poverty, military justice, and organised crime. His leadership role was most prominent in two inquiries.

One concerned Hepatitis C infections and was inspired by his meeting people accidentally infected through blood transfusions. He wanted their voices heard. As Senator Claire Moore said in the Senate, he wanted to ensure the blood transfusion service would prevent this problem ever occurring again. Second, from the knowledge derived from the inquiry, he wanted the professions to learn their lessons, such that the terrible stigma around Hepatitis B and C would be identified and addressed.

More famously, he chaired the inquiry into children in institutional care, which covered an investigation into the abuse of child migrants. The Forgotten Australians report led to Prime Minister Rudd making a national apology in 2009.

His voice breaking, in 2011 in his valedictory speech Hutchins observed: “These people’s stories are etched in my memory — the most reprehensible experiences and impossible to forget. We were all shaken to the base of our souls. Our hearts sighed. We were bewildered. We wondered time and time again how adults could do such things to children. How could men and women of faith routinely abuse boys and girls sexually, physically and psychologically? Why didn’t someone step in? Why were they able to get away with it?” It was an extraordinary speech about terrible events. Last year Senator George Brandis powerfully remarked in the Senate that Steve’s contribution on this issue was “testament to his overriding desire to see justice done to those to whom it had been denied.”

A long battle with cancer overwhelmed his parliamentary career from the start; there were three return bouts of the disease, which ultimately claimed him. In his final Senate speech six years ago he paid particular tribute to his wife Natalie Hutchins (née Sykes): “What sort of person marries a cancer survivor? What sort of person uproots her life, her comfortable existence in Victoria, to venture north? What sort of person acts as a nurse, caretaker, confidant and motivator? What sort of person takes on five stepchildren as friend and adviser? Only one very much in love, and one I love very much.”

He endured many rounds of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy initially at Nepean Hospital then at the Epworth in Melbourne; finally he was in the caring hands of his family and the Blue Mountains palliative care nurses.

He believed in the dignity of work, the right to organise and the vital role unions play in improving conditions and lifting living standards. A message from Kim Beazley was read out at the funeral: “Steve was a great example of how good our political and industrial movement can be… Grounded in that, he took that voice into a parliamentary career of substance, while never losing his original commitment… His was too short a life, but it was one of consequence and substance.”

Steve’s faith was vitally important and he was active in volunteering time to Catholic charities. He received the Last Rites and was surrounded by family at the end.

Last November his flag-draped casket left St Finbar’s Catholic Church, Glenbrook in the Blue Mountains, atop his green rosary beads, a picture of Jesus owned by his late mother, a memento from his time as an official with the Transport Workers’ Union and a plaque from St Vincent de Paul honouring his commitment to the poor. A maudlin Danny Boy played as the church emptied.

He is survived by his wife, Natalie – a Minister in the Victorian government, and their son, Xavier; his other children, Lauren, Julia, Michael, Georgia, and Madeleine; and his grandchildren Jacob, William, Edie, Nathaniel, Rorie and Audrey, as well as his first wife, Diane Beamer, who in winning the marginal seat of Badgery’s Creek in 1995 enabled Bob Carr to become Premier of NSW.

Note on Publication:

Michael Easson, a former Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, knew Steve Hutchins from their days in NSW Young Labor in the mid-1970s.