Published in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 18, 1981-1990, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, pp. 369-370, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/ross-lloyd-robert-maxwell-15927/text27128

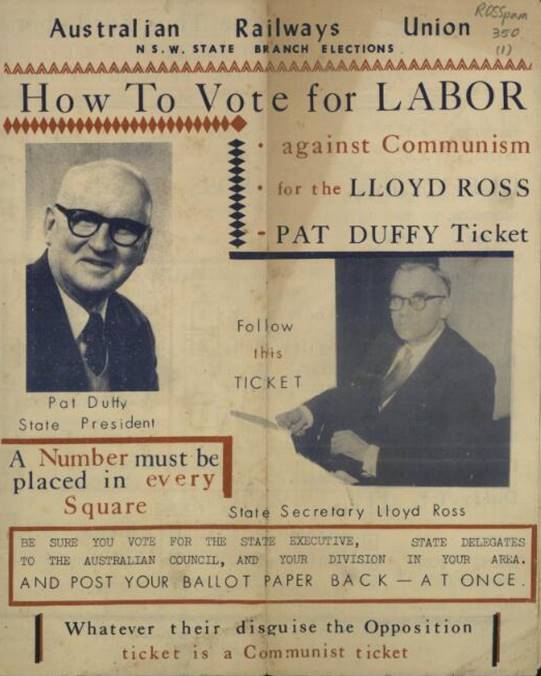

ROSS, LLOYD MAXWELL (1901-1987), labour intellectual, WEA tutor union official and writer, was born on February 28, 1901 in Brisbane, son of Robert (Bob) Samuel and Ethel (nee Slaughter) Ross. Another son, Edgar was born in 1903. Educated through scholarships at Melbourne University High and Melbourne University (1920-25) in Arts and Law, Ross worked for the Workers’ Education Association (WEA) in New Zealand (1926-1933), Newcastle (1933-1934), Sydney (1934-1935), then became NSW Secretary of the Australian Railways Union (ARU) (1935-1943), Department of Postwar Reconstruction (1943-1949), then the Melbourne Herald (1950-1952), then back to the ARU (1952-1969), then retirement. For over sixty years, he was active in labour affairs and in reflecting and writing about the movement.

His father, R.S. Ross (1873-1931), a compositor, journalist and labour activist had a formative influence; editing many of the major socialist newspapers in New Zealand and Australia including Maoriland Worker, Barrier Truth (Broken Hill), The Socialist (Melbourne), Ross’s Monthly (1915-1924 when incorporated into Union Voice, with RS Ross as editor). Whilst still at school, Lloyd Ross followed his father, then Secretary of the Victorian Socialist Party, in opposition to conscription during World War 1, as a member of the young socialists’ Y Club and in assisting with the management of Ross’ Book Service.

At university, Ross joined the staff of the Melbourne University student paper Farrago and was an inaugural member of the Melbourne University Labor Club. During his student days, he wrote for the Melbourne Herald newspaper. At the end of 1925, he accepted a position of tutor-organiser in adult education with the WEA in Dunedin, New Zealand. On February 2 1926 he married Christina Adelskold, an Australian of Swedish descent, in Melbourne, then six days later they both sailed to New Zealand.

At Dunedin Ross was also a Lecturer in Economic History at the University of Otago and organised education courses with the WEA and the University Extension Program, often in conjunction with unions.

During this time, the Great Depression hit and this caused Ross to rethink some of his positions. Awarded a Rockefeller Foundation travelling scholar grant, in 1929-30 Ross went to the UK & the United States, briefly studying at Manchester University and the London School of Economics, meeting up with many socialist intellectuals, including G.D.H. Cole; Ross’ researches were related to the Depression and writing a D.Litt thesis, later awarded by the University of New Zealand in 1935.

In 1933, he returned to Australia to take up the post of tutor-organiser with the Newcastle branch of the WEA, then closely affiliated to the University of Sydney, teaching on economics and international affairs.

In 1934 he was appointed Acting Assistant Director of Tutorial Classes at University of Sydney. Some of his WEA activities led him to organise lunchtime classes at Broadmeadow Railway Workshops in Newcastle; also plays and other semi-propagandist activity. This brought him into contact with members of the ARU. In 1935 Ross secretly joined the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), whilst retaining ALP membership. In the same year, a vacancy in the ARU opened. A combination of CPA, left activists and railworkers – knowing him from his WEA activities – successfully conspired to have him appointed as NSW State Secretary of the ARU.

Ross became active in agitating for improvements in rail workers’ wages and conditions, producing various pamphlets and propaganda, strategically taking industrial action, including strikes, and aggressively manipulating the industrial relations system. With Jack Ferguson, the ARU senior organiser, Ross toured NSW on the ARU’s two-seater Indian motorbike, dubbed “the red terror”.

When Ross joined the ARU in 1935, the union members were poorly organised, low paid and many suffered atrocious conditions. Ross did much to improve the “dignity of labour” and was one of many in the labour movement to effectively civilise capitalism. At that time, however, Ross saw his activities in more radical terms. Ross was concerned with health and safety issues – sandy blight and trachoma were problems faced by workers, as Ross discovered on visits to western New South Wales in the mid and late 1930s.

As World War 2 broke, Ross at first supported the CPA party line, but began to change his stance. At the NSW ALP 1940 Conference, Ross led debate on the notorious “Hands Off Russia” resolution, claiming that the Allies wanted to align with Germany and attack the Soviet Union. Soon, however, he grew disillusioned, reasoning from a Marxist, then a democratic socialist perspective that the CPA was an enemy of freedom and that the totalitarian menace was real. He resigned from the CPA in 1941, still remaining in the ALP. Together with Jack Ferguson, Ross was able to persuade a majority of his ARU colleagues to stick with the official Labor Party (rather than supporting the Hughes-Evans State Labor Party which eventually merged with the CPA in 1944). Ross supported Curtin, whom he had grown to respect. His political trajectory had returned him to an anti-Soviet, independent socialist position – which mirrored his father’s outlook. R.S Ross’ pamphlet Revolution in Russia and Australia (1920) argued for a democratic, socialist and Australian alternative to Bolshevism. In contrast, Lloyd’s brother Edgar stayed with the Stalinists, editing the Miners’ Common Cause newspaper, etc. After Chifley sent troops into the coal mines in 1949, the brothers never spoke again.

In 1943, Ross travelled to the UK & USA and later that year joined the Department of PostWar Construction, serving as Director of Public Relations. During his period in government, Ross was an Australian Delegate to Institute of Pacific Relations Conference, Canada, December 1942, and Australian Representative, Minister for Information, Britain, 1943. With the defeat of the Chifley government in December 1949, Ross was sacked by the in-coming Menzies administration. Then Ross returned to writing, hoping to write a biography of Curtin. He rejoined the Melbourne Herald. After a few years, in 1952 Ross returned to the ARU as NSW Secretary. His friend, Jack Ferguson, quit the union to join the NSW Milk Board, leaving the union rendered by ideological, albiet new splits.

Ross played a significant role in articulating a liberal and democratic socialist alternative to the sillier ideas of Left and Right in the labor movement. He had an impact on the ALP Industrial Groups in the 1950s and he hoped that this element would become a radical and thoughtful force within the Australian labour movement. His articles in the late 1940s and 1950s in the Catholic journal Twentieth Century laid the theoretical foundations for such a perspective. But this was to come to naught. Ironically, in his “movement of ideas” speech in 1954, given to the Melbourne Movement inner sanctum, B.A. Santamaria conveyed suspicion about his non Catholic allies, Laurie Short (in the Ironworkers’ Union) and Ross, fearing that they might embrace a “third way” and adopt the woolly thinking of soft leftists.

During the ALP split, Ross was one of the seventeen delegates who walked out of the 1955 National ALP Conference in Hobart. But that was as far as he went. Ross believed that the formation of the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) was a colossal mistake and a misunderstanding of labor traditions. As the Grouper NSW Labor Party machine fell, Ross was put forward as the Right candidate for party President, but was defeated in 1956. In NSW Ross and Short stuck with Labor and the “live to fight another day” strategy. In doing so, Ross helped minimise the impact of the Labor split in New South Wales.

The 1950s and 1960s were a period of significant technological change – introduction of diesels to replace steam engines, the electrification of the metropolitan rail network, country depot closures and relocations. Ross found this hard to manage with his union diminishing from one of the largest in NSW to a much smaller force. He advocated improvements in consultation and “worker participation” in management.

Ross was President, Australian Association of Cultural Freedom (publishers of Quadrant) from 1961 to 1968; Vice President of the Australian Productivity Council 1961; director of Elizabethan Trust and member of Sydney Opera House Trust (both in 1968). In 1969, he retired from the union. In 1972 an Order of the British Empire (OBE) followed.

His books were William Lane and The Australian Labour Movement (1937) based on his D.Litt thesis and his biography of John Curtin (1977), completed over thirty years after he started. A biography of his father, Red Blood and Black Ink: A Biography of an Australian Rebel, was not completed.

Ross died in 1987, predeceased by his wife and son David Allan (who worked in the Federated Ironworkers Association) and survived by daughter, Marea Lloyd and several grand children.

In many ways, Lloyd Ross was the odd man out. The first and only man to hold a Doctorate of Letters and a leading position in a blue collar union, an atheist amongst mostly Catholics in the NSW ALP in the 1950s, a labour intellectual whose mind turned to contrarian positions.

What can be said of Lloyd Ross’ career? Three things stand out. First, he helped a lot of people live better lives and think for themselves. More than that, he put bread on the table and did some magnificent things for rail workers. Second, he helped the ALP survive and added some substance to the debates then raging – especially in clarifying a credible, tolerant, yet proudly social democratic line. Third, although the record of his work is uneven, a number of articles and books Ross wrote are significant contributions to labour history. The articles he wrote for Labour Voice in the 1920s and 1930s, an unpublished biography of Frank Anstey, and the Twentieth Century articles stand out.

It is an interesting question whether Ross made the right decision to return to the ARU in 1952. He was immediately consumed by the faction fights and the exhausting work of a leading trade union official. But finding work elsewhere was hard. He was needed for new struggles. Once you’ve been there, a life of activity is hard to resist. Thus Ross had little time for reflection, research or writing. A different occupation might have given more time for intellectual activities and research.

Ross stood his ground on the issues he believed in. But he instinctively looked for allies, believing in coalitions of fractious allies that, depending on the cause, might include conservatives, liberals, laborists, social democrats, democratic socialists and people of no political allegiances. This made him a character who aroused deepest suspicion from those who were more narrowly aligned.

Lloyd Ross’ career is of great fascination given the events in which he was involved in and wrote about. Probably he would see getting unskilled rail workers – shunters, cleaners, tradesmen’s assistants and the like – more in their wage packet, better conditions, treated with respect and greater dignity, as the achievement that dwarfed all others.

Select Bibliography

Erroll G. Knox (editor), Who’s Who in Australia, IXth Edition, 1935, The Herald Press, Melbourne.

Articles published by Ross in Foreign Affairs, Morpeth Review, Twentieth Century, Quadrant, Australian Highway, Labor Digest, Meanjin, New Zealand Highway, Australian Outlook, Australian Journal of Politics and History, Australian Quarterly, etc.

Lloyd Ross Papers, NLA

Stephen Holt, A Veritable Dynamo: Lloyd Ross and Australian Labor, 1901-1987.

Postscript (2015)

I hope one day to edit a selection of Ross’ writings. He was an uneven essayist, but when he was good…