Published in The Australian, 14 March 1997, p. 17.

Albert Shanker, born New York, September 14, 1928, died New York, February 22, 1997, aged 68.

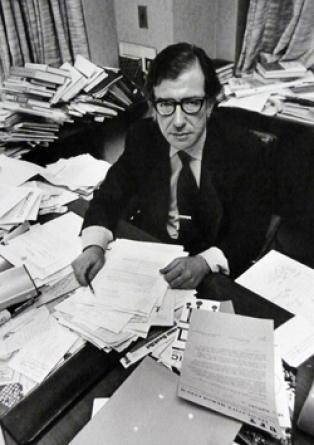

Albert Shanker, union leader, intellectual, social democrat and raconteur was one of the greatest American labour leaders of his time. As President of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) from 1974 until his death, he was at times both militant unionist and adviser to US Presidents ranging from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan and George Bush.

“Al spent his life in pursuit of one of the noblest of causes, improvement of our public schools,” President Bill Clinton said after Shanker’s death from cancer. “He challenged the nation’s teachers in schools to provide our children with the very best education possible and made a crusade out of the need for educational standards.”

He was respected across the political spectrum. Texan billionaire and independent presidential candidate Ross Perot, who wrote a report for the State of Texas on education reform in the middle 1980s, praised his contribution to the debate on education standards. Shanker, however, was also a significant force within the Democratic Party and played a leading role as a moderate Democrat during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Shanker was born in New York in 1928 to Russian Jewish immigrant parents and raised in Long Island city. His parents were involved in the garment trade; his mother was a member of both the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Union.

He graduated from the University of Illinois in 1946 and later studied philosophy at Columbia University. After completing his studies he commenced employment as a school teacher. In 1964 he became President of the New York City United Federation of Teachers, holding this position until 1968.

From 1974 he was national President of the AFT and was also a vice-president of the American Federation of Labor Organizations-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), the American equivalent of the ACTU. In the last few years he led talks between the AFT and the National Education Association in an effort to merge the two organisations and form a more effective voice for children and teachers. Talks are continuing.

Shanker’s influence in the United States transcended the usual role of union leader. He wrote regularly for The New Republic and The New York Times and other outlets. His articles were crisply written and traversed a wide range. In the last month of his life he wrote articles on Baynard Rustin, the Civil Rights leader, the case against school vouchers, the role of teachers and curriculum content in schools, and violence in school grounds.

He was a lifelong social democrat and a member of the National Advisory Council of Social Democrats, USA. His long-term Secretary, Yetta Shachtman, who died last year, was the partner of Max Shachtman, one of Trotsky’s original proteges in the US and the author of The Bureaucratic Revolution. Shachtman later broke with Trotsky, arguing against the concept of Soviet Union as a deformed worker state in emphasising, à la James Burnham the bureaucratic nature of Soviet society. It was this powerful critique of the Soviets combined with an intellectual diet of Orwell’s essays that informed Shanker’s political outlook.

From afar Shanker could be seen as a cold war warrior, but he was many things. Woody Allen’s 1973 comedy ‘Sleeper’ includes a reference to his famous combativeness. The lead character, played by Allen, wakes up after a two-century hibernation to be told that civilization was destroyed, “200 years ago [after] some guy named Albert Shanker got a hold of the bomb.” I once asked him whether this was a reference to his status as a fierce anti-communist or something else. Shanker said it was probably because he had led several strikes in New York in the late 1960s. He was jailed twice for illegally shutting down schools.

At one time, in the late 1960s, opinion polls had him as more popular than any other potential candidate for Mayor of New York. He turned down all invitations to seek political office, saying “union work is where I belong.” He was passionate about the public school system and the importance of high standards in enabling students from deprived backgrounds to do well.

Shanker played a major role in the late 1970s in the Labor Committee for Trans-Atlantic Understanding, which gathered together a number of social democratic leaders including Helmut Schmidt from Germany, Mario Soares from Portugal, and some of the leading social democrat figures in Great Britain (prior to many of them leaving the UK Labour Party).

His Australian connections began with the formation of the Labor Committee for Pacific Affairs in 1981. This group attempted to campaign against far leftist influence in the Pacific and led to numerous attacks by the far left in Australia that it was linked to the CIA.

At the 1988 International Confederation of Free Trade Union Congress in Melbourne, Shanker was part of the American delegation. Following a number of exceptionally long-winded speeches, Shanker turned to me and quipped, “When Marx said ‘workers of the world unite!’, I’m sure he didn’t know that when they did they’d all bore themselves to death.” He had a nose for detecting pomposity and his feel for the black ironies of life informed his sense of humour.

Shanker’s ideas on education are likely to be his most enduring influence. NSW Premier Bob Carr and his Minister for Education and Training, John Aquilina, would sometimes quote from an article written by Shanker in The New Republic in the debates in recent years on school standards in NSW.

In one of his last articles he dealt with the issue of content in the school curriculum: “Prospective teachers are often indoctrinated with the idea that they should ‘teach the students, not the subject’ this means focusing on the process of learning – on ‘problem solving’, ‘higher order thinking skills’ and ‘critical thinking’… the terms may sound impressive, but without content, students don’t have anything to think about – or, probably, any interest in thinking.”

He went on to argue, “our reforms must re-establish the pre-eminence of subject matter by setting standards that focus on content and curricula and assessments attached to these standards. When this happens, content will assume its correct place in preparing young teachers… then teachers… who are in love with their subject… will once more be the models to which everyone in the profession aspires.”

He is survived by his wife of 35 years, the former Edith Gerber, and three children, Michael, Jenny and Adam; a son from an earlier marriage Carl; and three grandchildren.

Postscript (2015)

Shanker was one of the great, entrepreneurial union leaders of the United States and his impact was felt far and wide.

I met him in 1983 through the Labor Committee for Pacific Affairs. He visited Australia as a leader of a union delegation hoping to forge alliances and friendships with like-minded union leaders. He found affinity with the leaders of the Labor Council, particularly Barrie Unsworth.

Al thought of himself as a Cold War liberal or, as he would also say to Europeans and Australians, a Cold War social democrat.

He opposed tyranny, arbitrary and abusive exercise of authority. That opposition and his passion for freedom, for the full flowering of every individual, were the poles by which he set his course, in the union, on education challenges, in politics.

I got to know him well and read the articles he published in The New Republic and the New York Times.

He was prolific, articulate, and provocative. Bob Carr and, later, John Aquilina, the Shadow and later NSW Education Minister, drew solace, inspiration, and ideas on what Shanker mostly wrote about — namely, education.

I found Shanker extremely well read and passionate about disadvantage, about the evil of racial inequality, about the role of teachers in providing a helping hand and more to poor kids.

Therefore, he hated education fads, lack of standards and lazy pedagogy which proposed that kids could explore the world in some deregulated, free of structure, way. By all means encourage creativity and imaginative teaching methods. But learn the fundamentals first, empower kids through rigour, monitoring, continual improvement and testing. Not for rote learning, but to enable ordinary folk to get ahead.

He entertained unconventional ideas, even charter-school ideas within the public education system. He was the most powerful, enlightened, and passionate advocates of public education. America socialises and remakes itself in classrooms. No one should be left behind.

I met him on visits to America and again in March 1988 when he revisited Australia for the worldwide conference of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions.

He was at home chatting to Ross Perot on STEM education, Social Democrats USA folk on political challenges, to President Clinton on education reforms in modern America. The latter awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is fair to say Shanker was respected across the political divide. He had opinions and he was not afraid to speak up for them.

One time in Washington devouring lunch at a restaurant, Perot walked by with an entourage. Afterwards, outside, Shanker briefly introduced us. There was a warmth between them.

Another occasion, in 1996 I was in New York and attended a public memorial for Yetta Shachtman, Al’s long-time assistant, the widow of the late Max Shachtman.

Shanker knew enough about the ideologies of the left, to suggest he himself might have flirted with more radical positions as a younger man.

Shanker told me that as an organiser of the Union in New York, he campaigned for pension reform, coverage, and minimum benefits. His efforts and those of many others were instrumental in reinvigorating the Teachers, Insurance, and Annuity Association (TIAA), as it is now known.

There are so many areas where and with so many people that he made an impact.