Article submitted to the Australian Financial Review in February 1995.

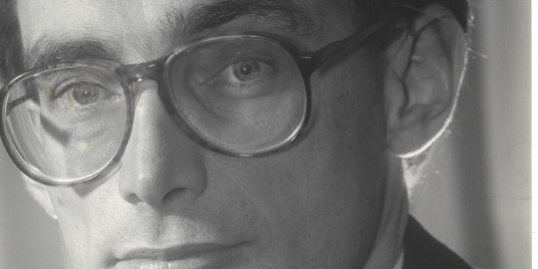

From the forests of the Northern Tableland to the wilderness of mirrors in the NSW Legislative Assembly, Bob Carr has trekked all over the state in search of political mileage.

In 1991 everyone wrote him off. But his flair for popularising a critique of the Greiner government as mean spirited almost won him victory. Had the informal vote not been so unusually high, he might have become Premier there and then.

As Malcolm Mackerras mentioned on these pages a few weeks ago, Carr is the most interesting of today’s crop of would be and current Premiers. He labours, however, hard against the image of the book-owl, decaf espresso-drinking philosophe – more at home on the left bank of Paris or in Washington than at a rugby league club in Sydney.

In the current NSW election campaign, there has been plenty of mischievous talk about Carr being bored with state politics; it is said that his real love is foreign affairs rather than the drudgeries of a state pollie.

Those assessments of Carr are caricatures. Some of the critique reflects an uncomprehending approach to public life and the challenges associated with state politics.

But it is also true that Carr is an enigma shrouded in mystery. He is a hard man to get to know. So what motivates him? Who is the real Carr?

Bob Carr joined the party as a teenager at Matraville High School. Back then he was an enthusiastic supporter of Bob Heffron – who assumed the premiership in 1961 at the age of seventy. Thank God youthful enthusiasms are not always long lasting!

One thing to note about this background is that, as the son of a tradesman family with an engine-driver father devoted to the memory of Ben Chifley, Carr came from a home that understood a quid is a quid.

Typically such backgrounds encourage – if not instil – a belief in “sound money”. You do not spend what you do not have. He came from a modest family that made ends meet.

It is true that Carr, like lots of intelligent sons of the working class, transcended his origins. Too much can be made of this phrase. We all do. Everyone is uniquely different from the last generation.

At school and at university, Carr cultivated his debating skills, with an eye for clever turns of phrase and argument. In Young Labor he was one of the golden-tongue orators mocking the Left’s pretensions.

After he joined the Labor Council of NSW as education and publicity officer, he joked that he was Minister for Propaganda in the Ducker Administration.

That quip is a reminder of a side of Carr that most people do not see – his sense of the absurd. In politics, it should be a vital part of a politician’s psychological make-up.

Once, more recently, Carr riposted to a friend that being premier of NSW was once a prestigious position of note in the community. With John Fahey at the helm, however, it reminded him of the situation in some local councils, where the councillors decide to give everyone a turn at being Mayor!

Carr is a clever wordsmith. In his pamphlet Matters of Principle (1989), Carr’s rhetorical flourish purpled through the polemic:

Only through a public assumption of responsibility for education, health, transport and law and order will we avoid becoming a squalid society. Otherwise we face the Manhattan option for New South Wales: dirty, unsafe public transport, inferior schools, hospitals run by contractors, homeless sleeping in doorways, but at the other end of society, a bubble of ostentatious prosperity and the worst excesses of casino capitalism. It is in this direction that NSW Incorporated now veers.

But is this all there is – a quick-witted politician?

No. Policy concerns are at the heart of Carr’s interest in state politics. Indeed, the idea that there is something extraordinary to be interested in state issues deserves to be hit on the head.

Carr’s interest in the environment, education and social justice are about matters that state politicians have the most important say in the Australian federal system.

Also, the debate about the Hilmer reforms and, for that matter, the Greiner government’s achievements in addressing some areas of statutory authority reform and performance in NSW, is a reminder that state governments perform significant tasks.

In the education field, Carr has sometimes delivered speeches that give a strong clue about his outlook. His defence of the canon, of standards, of the importance of testing and examinations is – at the heart of it – an articulation of the protection of the open society. This is a plea that every kid get their chance: not just in some liberal sense of equality of opportunity. Carr’s view is that without an understanding of the language, the core competencies, the culture, kids are unable to make a useful contribution to improving themselves or society.

Carr is absolutely passionate about such things. In the words of Saul Bellow, “words are a poor boy’s best friend.”

Carr’s judgement as a strategist and tactician is credited as key to the result in the 1991 poll. This time round, however, it appears that the election result is a lot messier than it seemed earlier in the year. Labor’s campaign is to fight the NSW poll as 99 by-elections. NSW Labor is giving new meaning to Tip O’Neil’s idea that all politics is local.

The tone of the statewide campaign is unexciting. The only bright moment would have been an eclipse. This is a pity. Because Mr Carr is a much more interesting figure than what the campaign is showing.

Postscript (2014)

I suspect the editors of the AFR thought this piece too favourable to Carr and about a happenstance (his premiership) almost certain not to transpire.

This was written two or three weeks before the March 1995 NSW state election. It was my effort at presenting the best case for Carr – and to reveal that behind the mystery lurked an interesting character who might have a decisive impact for the good in NSW politics.