Published in the Australian Financial Review, 11 June 1994, p. 18.

For those who think that ideas do not matter much, that the arcane debates within the socialist tradition are mostly irrelevant, the death two weeks ago of Alex Nove (1915-1994) will pass as something of little moment.

On the surface, Nove’s claim to fame might appear ridiculous. How could anyone who devoted most of his life to an examination of the workings of the Soviet economy and the theoretical pretensions of socialism be taken seriously? Communism is dead in Europe. In China the workings of commo capitalism have little to do with the ideas of the classic socialist and communist tracts; “white or black, so long as a cat catches mice” (Deng’s recipe for the Chinese way) is a mile away from Marxism-Stalinism-Maoism, although totalitarianism still flavours the mix.

Except for the lingering Marxist strongholds in pockets of the universities, it is now possible to regard academic excellence in the study of communist economics as something very quaint; something akin to a professional expertise in 14th-century Islamic ceramics.

However, Nove’s contribution to economic and political debate is likely to be more influential than as a figure on the margins of economic and political theory.

His studies of the Soviet Union constitute the bulk of his contribution to intellectual life, especially his Economic History of the USSR. One thing that distinguished Nove’s writing was its capacity to be critically entertaining as well as thorough, sceptical of sources and firmly argumentative.

Anyone who could entitle a book Was Stalin Really Necessary? knows about the (grim) ironies of the Marxist dialectic and the Soviet “experiment”. Given the scientific claims of Soviet socialism, it is a good question to ask and try to answer: Would another Stalin have emerged if the really existing Djugashvili had not been born?

Is despotism consequential to Marxism-Leninism? Nove thought the whole enterprise was bound to fail and promote misery. As he put it in his monograph, Marxism and “Really Existing Socialism”, Marxism had little of value to contribute to the debate about socialist economics, except in a negative sense.

Amongst his many articles and books, his essays on the Allende experiment and critiques of modern economics – many of these collected in the book Socialism, Economics and Development (1986) and his book Efficiency Criteria for Nationalised Industries (1973) stand out. But his major contribution is his discussion of the role of markets and socialism, and speculation about the possibility of market socialism.

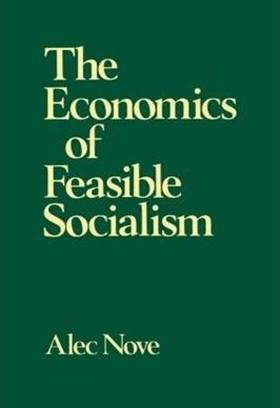

Of all his books, The Economics of Feasible Socialism, which advocates a democratic, market-oriented socialism, is likely to be the most influential. Widely translated, the book ignited an informed debate in the last decade of East European communism and helped to undermine the remaining credibility of State Socialism.

The book also influenced some Left ideologues in the West. Australian Left MHR Lindsay Tanner and Australian Conservation Foundation chief, Trish Caswell, have quoted from Nove without fully understanding his liberal, social democratic credentials.

In the preface to The Economics of Feasible Socialism, he comments: “Brought up in a social-democratic environment, son of a Menshevik who was arrested by the Bolsheviks, I inherited a somewhat critical view of Soviet reality: if this really was socialism, I would prefer to be elsewhere. (Luckily I was elsewhere).” He escaped in the 1920s with his family. The book is questioning, lively and clever. It even includes two book reviews written by Nove – one written by the imaginary editor of The Revolutionary Worker: “Let us …imagine that the reviewer is a serious, committed, intelligent dogmatist, and that he would not be satisfied with mere denunciation: he will not speculate on how much the author was paid by the CIA, or assert that the ideas expressed are indistinguishable from those of the Chicago school. In other words, he proposed to launch a serious attack.”

The other imagined reviewer is “sharpening his sword at the Institute of Economic Affairs. Socialism is to be rejected and a reasonable-sounding version is to be more vigorously condemned, since (it will be argued) it would surely degenerate into centralised tyranny, would in the end be ‘the road to serfdom’, as Hayek would certainly say, even though I would be credited with the good intention of avoiding such an outcome”.

Someone who writes like that is genuinely interesting and alive to contrary arguments.

In a recent work, The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited, Nove re-emphasised that his work on market socialism was aimed at both the Left as well as the Thatcherite neo-liberals.

However, he was not sure that market socialism, however strongly he might advocate its credibility, might work in a sensible, economically and socially efficient way. Nove did not necessarily fully believe in his case. He wanted to put the best argument forward. Indeed, in practical politics, he became an active supporter of the Social Democrats (against British Labour) in the 1980s.

In October 1988 I met him in Edinburgh. He was brilliant in discussion, rapidly moving from point to point, cracking jokes and excited by a recent conference with Soviet émigrés in Barcelona from where he had just returned. There had been an enormous shift in the openness of Soviet society. He was writing a book on the cultural revolution in Russia (eventually published in 1989 as Glasnost in Action).

He loved to put up an argument and run through the reasons why it might be faulty. He spoke as well as he wrote.

Nove told me that it was becoming very clear that no-one was “in control”, that the absence of market mechanisms meant that nothing was organised efficiently.

He asked me whether I had heard about the CIA man and the KGB agent who caught up with each other in Paris. The KGB fellow said: “While we are here, why don’t we share some secrets. Tell me, this Chernobyl nuclear disaster, was this the CIA’s work?”. “No”, the CIA spy replied. “Nothing to do with it. But if you want to know something really successful it’s Agropod. Now that’s our invention!”

(Agropod was the State bureaucracy for the organisation of the notoriously inefficient agricultural sector.)

Postscript (2015)

While on a visit in 1987 to the UK organised by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, on the strength of having read Nove’s The Economics of Feasible Socialism (1983) I asked to meet him. I did so at a restaurant in Glagow on 31 October 1987. He arrived looking busy with an old briefcase; he took off his plasticized jacket and headed to the table. Strikingly, his sidelevers dominated between his eyes and cheeks. Nove was brilliant in discussion, moving from point to point, discussing a recent conference in Barcelona (from where he had just returned), a conference in Moscow, and one which had taken place in Edinburgh last year – all on emerging changes in the Soviet Union. This was in the days of Mikhail Gorbachev’s rule as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (which he led from 1985 until dissolution of the USSR in 1991). The Barcelona and Edinburgh conferences involved a number of émigrés and Soviet academicians and Nove told me of the enormous shift in openness and optimism by those he had met. He believed permanent, real change was happening in the Soviet Union. Life after the Cold War was in prospect.