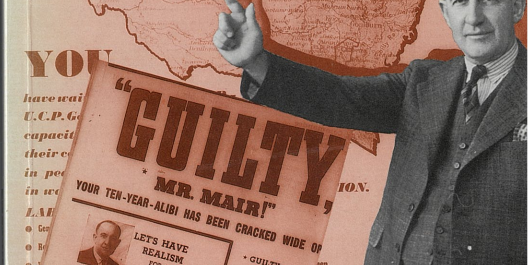

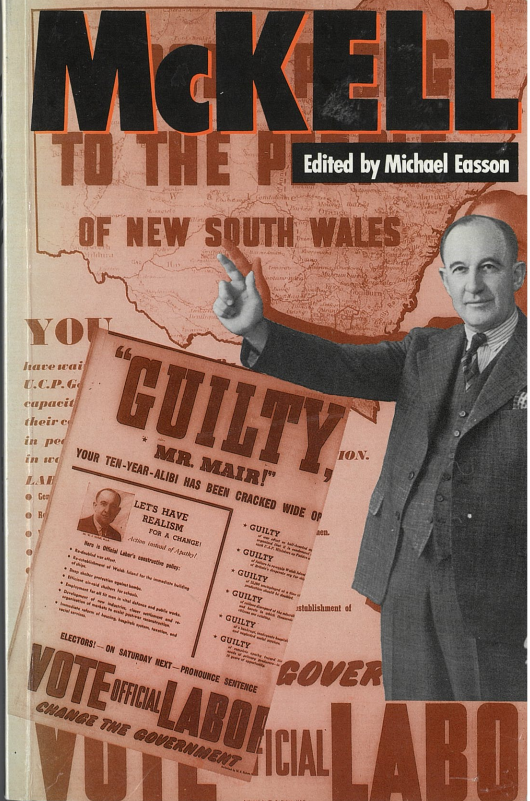

Published as the ‘Introduction’ to Michael Easson, editor, McKell. The Achievements of Sir William McKell, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988, pp. xv-xxiii.

As a young boy William John McKell watched a procession of men and women marching by the Sydney Town Hall on 26 January 1901. They were celebrating Australia’s birth out of the six federated colonies. McKell noticed the unionists – some from as far away as Broken Hill -marching behind magnificent banners on that day. Here was a ceremony where ordinary men and women participated proudly and equally.

McKell was born in the very year that the Australian Labor Party was formed and in many ways his life was shaped by the diverse elements within the labour movement. Joining the party in 1906 he came under the influence politically and spiritually of James McGowen, Sunday School superintendent at St Paul’s, Redfern, local MP and later, in 1910, the first Labor Premier of New South Wales.

As a young apprentice McKell showed that servility was not in his character. Outraged by the successful efforts of the employers to extend the period of apprenticeship in his trade from five to six years he cajoled his union, the Boilermakers Society, to oppose the employers and revert to the previous period of indenture. McKell became active in this union representing it at the Labor Council of New South Wales and the Eight Hour Day Committee and he attended classes conducted by the WEA on economics and industrial advocacy. He rose to the position of assistant secretary of his union and participated in the industrialists or trade union based faction of the party, which successfully controlled the 1916 Conference.

But for McGowen’s defection from Labor ranks in 1916 over the conscription issue, McKell may today be remembered as a former prominent union official. In 1917 McKell allowed himself to be persuaded to seek Labor endorsement and election as member for Redfern against a man he had known and admired and from whom he had learnt much about the labour movement.

He easily beat McGowen, who stood as a Labor independent at the elections in 1917. Unlike many in this period, McKell found it difficult to hate old mates and he remained on friendly terms with McGowen until his death in 1922. As McKell said in his maiden speech “I have remained true to what he taught me and I intend to remain true.”

His maiden speech raised a number of themes which continued to occupy his political and parliamentary career. These included an admonishment of the conservatives for their attack on Labor’s legitimacy to govern (on the basis of sectarianism, the war, the IWW and claims about ‘disloyal’ elements dominating the party), the unfairness of the industrial relations system, the inefficiency of the agricultural industries, the obstructiveness of the Legislative Council. McKell referred to the Nationalists as “bound by more than a mere executive, they are bound by the great financial interests…”

For the whole of his life McKell was an advocate of gradual improvements and a champion of parliament as the forum and place for achieving many of Labor’s reforms. His criticism of Holman was that he failed to make use of the opportunities to implement Labor’s program, particularly in the industrial area. His opposition to Lang was because Lang was a failure who could not (after 1932) win government and who in 1925-27 and 1930-32 squandered the unity of the party and caused it to lose some of its ablest members and supporters. Sometimes issues arise which lead people to turn their backs on the party, but Lang was eager to provoke defections and expulsions and engage in factionalism on an enormous scale.

After fifteen years of Bonapartist leadership Jack Lang’s period as New South Wales Labor leader finished in September 1939 with McKell’s election as New South Wales Labor Party leader and as Leader of the Opposition.

New South Wales Labor leaders typically combine three qualities – dreamer, stabiliser and fixer. Usually one characteristic dominates. Stabilisers are sound party people who generate public confidence and respect. Dreamers have their vision in mind, inspiring many but not all of their followers. Dreamers can be crash-or-crash-through types or cautious idealists. Fixers have a strong factional base and are skilled in wheeling and dealing among the personalities and divisions in the party. Fixers are usually admired but not trusted.

The election for leader of the parliamentary Labor Party in 1939 was between three types: Lang (primarily dreamer and fixer), Heffron (dreamer, fixer, but not really a stabilizer – he had been in and out of the New South Wales Labor Party between 1936 and 1939) and McKell (stabiliser and dreamer, with little factional nous but with enough experience and support to assist him to be a fixer).

As a leader of the Labor Party, McKell set out to unite the party by hammering the opposition’s weaknesses and focusing the ALP’s attention on the selection of candidates and policies appropriate for government. Unity, victory and successful government were McKell’s aims and consecutive achievements.

In his 1941 policy speech McKell promised no wholesale radical reforms. No nationalisation planks, repudiation of foreign debts or violent rhetoric featured in Labor’s election pledges. McKell promised dams, electricity, soil conservation assistance and new sche1nes for marketing agricultural produce to the country. He appealed to the electorate on the issues of repeal of the UAP’s wages tax, fighting the war more effectively, housing and slum clearance, improvements in industrial law and workers’ compensation and efficiency in the use of government resources. McKell campaigned on the basis that he could be trusted. There was nothing wild or eccentric which would offend the electorate.

McKell won and was able to build on his victory three years later in a massive win.

Five years into his period as Premier, McKell produced a booklet, Five Critical Years, the opening quote of which are some of his words: “What sort of nation would it be if the people had no pride in their achievements?” Those words and the booklet indicate McKell’s sense of tradition and pride in what he had achieved in politics. Interestingly, the achievements mentioned in Five Critical Years covered areas where McKell was convinced the government had improved the standard of living of the average person. The booklet was a text of labourist thinking and priorities for the 1940s. The major themes were economic development, protection of health and working conditions, improvements in the areas of babies’ nurseries, educational reforms, government insurance, the Housing Commission, the State Dockyard, State Brickworks. Cultural pursuits and the enviromnent were also listed as highlights.

Towards the end of his period as Premier, McKell addressed a meeting of the Henry Lawson Labor College on the government’s achievements, comn1enting: “It is Labor’s job to help lift the world from the morass into which it has fallen” and that “I can see no better start than to have our people think not purely in terms of the material, but of what they can learn from a cultural education.” Funding for the Art Gallery, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Mitchell Library, school and public libraries, travelling exhibitions from the National Gallery to country centres and bursaries for secondary students were cited by McKell as significant priorities of his administration.

McKell is not only remembered today because he was a successful politician (for example, the first New South Wales Labor leader to win two consecutive elections). This was immensely important both in gaining and retaining political power and in easing the path for Curtin to become Prime Minister: in Lloyd Ross’ opinion: “It was not until W.J. McKell… was elected Premier of New South Wales in May 1941 that the public was convinced Labor should be given another opportunity to govern” at the federal level.

Two electoral victories are not enough to secure a substantial and lasting political reputation. After all, McKell’s successor, Jim McGirr, won several elections yet no one is ever likely to write much of his career. McKell let it be recorded in his entry in the Biographical Register of the New South Wales Parliament that he “Voted for R.J. Heffron as successor”. He confided with the author that the momentum for reform begun in 1941 stopped with McGirr’s accession to leadership.

McKell is venerated within the New South Wales ALP for a mix of reasons: style, strategy and substance. Turner and Clune describe the kind of successful politician McKell was in and out of government – pragmatic with a realistic sense of achieving Labor ideals.

Hansen’s analysis of the 1941 election win emphasises the strategy of winning the bush as important to the electoral success of the party. Goot debunks the importance of this strategy and draws attention to the fact that rural electorates have played a lesser and lesser part in the selection of governments and the election of Labor governments throughout this century as populations in rural areas have declined.

An issue for Goot’s analysis is the answer to the question: ‘How important was the McKell strategy of winning and retaining country electorates to the long term survival of Labor governments?’ An answer to this is indicated by the electoral results in the closely fought New South Wales elections of 1950, 1956 and 1959. The 1950 elections left Labor with a majority of two – including the core rural seats of Bathurst, Burrinjuck, Castlereagh, Goulburn, Liverpool Plains, Monaro, Murrumbidgee, Sturt, Wagga Wagga and Young. Six of these seats were won in 1941. In addition, the new seat of Burrinjuck was largely based on Yass, which W.F. Sheahan first won in 1941. (Bathurst, Goulburn and Sturt were already Labor seats.) Similarly the 1956 elections, after which Labor’s majority was six, required Labor to rely on these seats and two other core rural seats won by Labor – Mudgee and Dubbo. After the 1959 elections, where Labor’s majority was slashed to four, there were still five core rural seats held by Labor, which were captured at the 1941 elections – Burrinjuck (won as Yass in 1941), Castlereagh, Liverpool Plains, Monaro and Murrumbidgee. There were also four other core rural seats – Bathurst Sturt, Mudgee and Lismore.

The conclusion to be drawn from this is that the core rural seats won in 1941 by McKell, which continued to be held by Labor in subsequent periods, were crucial to Labor holding on to slim majorities at several elections in the 1950s. If one accepts that sitting members in rural areas generally sustain smaller swings against them, then the importance of McKell’s rural strategy is obvious: winning those seats provides a buffer for when the swing is on.

The contributors to this volume are in no sense eulogisers of McKell. All of them to varying degrees admire McKell’s achievements, but their chapters have been written to explain events rather than obscure them in hagiography. The best of Labor governments is, in the end, only a government composed of members for whom behaving decently and sensibly is always something of a strain. McKell more than most politicians was aware of this.

Turner sets out in brisk terms some of the major events and characteristics of McKell’s political life arguing that by 1947 McKell’s vision was frozen. Nairn covers 22 years of McKell’s period as a politician from his election as member for Redfern in 1917 to his election as leader of the party in 1939, describing McKell as a social democratic leader. Rawson spotlights the issues, events and faction leaders dominant during the internal battles within the New South Wales ALP in the 1930s and 1940s. Anyone with an appreciation of the difficulties of following the schisms and splits of this period will be grateful for this paper’s publication.

The Hansen, Clune and Goot contributions to this volume offer a variety of interpretations of McKell’s electoral and strategic achievements.

Chris Cuneen’s paper explores the rights and wrongs of McKell’s decision to grant a double dissolution to Prime Minister Menzies before the 1951 election. This event destroyed McKell’s reputation throughout much of the Labor movement. A quarter of a century would pass before McKell’s reputation was rehabilitated within New South Wales Labor. It has also taken the same period for academic interest – more excited by a dreamer like Lang than McKell – to focus on McKell’s contribution to New South Wales Labor.

The revival of the McKell legend was due to three people: Neville Wran, John McCarthy and Bob Carr. Goot refers to the interest Wran took in McKell’s country strategy before and after gaining office in 1976. Apart from Heffron, Wran was the only leader of the New South Wales parliamentary Labor Party for several decades to take a detailed interest in the career of McKell and strike up a friendship with him. In 1976 John McCarthy, a Sydney barrister with an interest in labour history, gave a speech to a seminar conducted by the ALP. He argued that McKell was the finest son of New South Wales Labor and that the motto of the party should be the same as the Scots Guards, ‘May We Be Worthy of Our Fathers’. McCarthy’s popularisation of the McKell myth influenced a number of his friends: Bob Carr, then working with the Labor Council of New South Wales as its education officer, met McKell and, a year later, wrote a profile for the Bulletin. Jack Hallam, an organiser for the ALP in the bush later to become an MLC and Minister for Agriculture, wrote several papers on McKell, which were widely circulated. Hallam later wrote a book on New South Wales country Labor, The Untold Story, several chapters of which were devoted to McKell.

The New South Wales ALP’s ruling group began to organise training schools for young party members which, from 1982, became known as McKell schools. In the same year the New South Wales administrative committee, at the suggestion of Stephen Loosley, commenced the McKell Lectures of which four have so far been given.

Earlier in 1978 the McKell Prize for the Environment was inaugurated by the Premier to reward an individual for his or her contribution to improvements in the environment.

In 1981 the Labor Council of New South Wales decided to organise a major function in the Sydney Town Hall to celebrate the council’s 110th anniversary – the guest of honour: Sir William McKell. He was especially grateful for a scroll of honour presented by the then secretary of the council, Barrie Unsworth.

Over a six-year period, 1976-82, McKell became synonymous with New South Wales Labor: Carr’s article in the Bulletin on McKell was significantly entitled ‘How NSW Labor Developed Its Nifty Image’. Despite the revival of McKell’s popularity within the labour movement, very little has been written about his period in New South Wales politics, his governments and his governor-generalship. This book fills a number of gaps, but a detailed and comprehensive biography still remains to be written.

This book is being published in the interest of and for Labour history, to foster a critical awareness of McKell’s contribution to public life.

Postscript (2015)

I was an active member of the executive Australian Society for the Study of Labour History (ASSLH), Sydney Branch, and a member of the board of their The Hummer journal. The Society sponsored a seminar on McKell on 11 November 1984 (The Hummer, No. 7, October/November 1984). The launch of the book was under the auspices of the ASSLH.

Barrie Unsworth suggested I put together the book resulting from the seminar. I commissioned all the articles, edited everything in conjunction with John Iremonger (1944-2002), who was working at Allen & Unwin, publishers.

I was particularly glad of Don Rawson’s article as, prior to reading what he wrote, I found the complexity of 1930s NSW ALP politics, splits and tensions, unfathomable.

Iremonger urged that I hunt far and wide for illustrations. So, I spent considerable time in the Mitchell Library. The State Library of NSW’s photographic department distilled to attractive photographs many of the illustrations to the book.

Barrie Unsworth, who wrote the Foreword, suggested the sub-title (“The Achievements of Sir William McKell” which appeared inside the book, but not on the front cover. In retrospect, my mistake: those words might have made the book sound like it was merely cheering for everything McKell).

Readers can see the book contained many perspectives, some more critical than others, of McKellism, what McKell sought to do, fell short on, where he failed, and his blind spots.

McKell was an attractive personality, keen to do “Labor things”, unusually diligent in undertaking research and exploring what was happening in other places, to fashion solutions to local circumstance.

I enjoyed meeting him many times in the last five years of his life.

McKell’s substance and style of government was the example that NSW Labor premiers Neville Wran, Barrie Unsworth, and Bob Carr most sought to emulate.