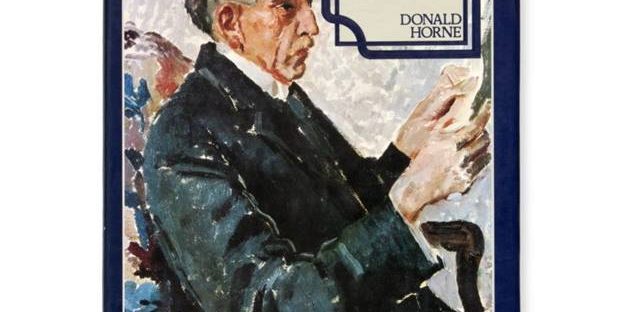

Review of a book under the same tile by Donald Horne, Labor Leader, Vol. 4, No. 1, November 1979, p. 7.

William Morris Hughes debauched Australian politics for more than a generation.

In the ninety long years of his life he was a member of six political parties – two of which he had himself formed.

Donald Horne’s portrait In Search of Billy Hughes reveals the hollowness at the centre of the Labor Party’s greatest ever rat.

In his book, Horne reveals Hughes as a chronic liar and power-crazed politician.

Only Malcolm Fraser rivals him as the most divisive political leader Australia has witnessed.

It was Billy Hughes, the great ‘patriot’ who divided the nation over the referenda to introduce conscription. The tensions in the Labor Party over the war were rent asunder and the labour movement – the ladder for Hughes becoming Prime Minister – was kicked into oblivion, never to govern again until the 1929 election, two weeks before the Great Crash of Wall Street, which ushered the Great Depression.

Cannon Fodder

When Hughes returned home in 1916 from campaigning in Britain on the jingoist platform of an even greater war effort, The Worker newspaper of the Australian Workers’ Union greeted him with the headline ‘Welcome Home to the Cause of Anti-Conscription’. It was inevitable that the Labor government would splinter. Donald Horne describes the circumstances:

Into this climate comes Hughes besotted with the war’s excitements, elated with his lionizing in Britain, and susceptible to pressures (enticements also?) in both Britain and Australia to increase Australian supplies of cannon fodder (and perhaps also wondering how to win the next election.)

He had not the faintest talent in acting like a conciliatory national leader, if the thought had occurred to him. It might have seemed a kind of treachery to the war.

So in this explosive atmosphere little Hughes lights a match.

This match ignited the fuse, which caused the Labor government to explode and a conservative-dominated, though Hughes-led, government to rise in its place.

What did Hughes gain from his betrayal of the Labor cause?

He would govern Australia for another 6 years until his political execution in early 1923. Earle Page, the Leader of the Country Party in the last weeks of Hughes’ Prime Ministership, called for the replacement of Hughes’ “thinly disguised socialism and theatrical posturing with a return to clean government of those who believed in self-reliance, individual enterprise and private initiative.”

Once Hughes had served his purpose, the conservatives clamoured for the return of a ‘safe’ leader – Stanley Melbourne Bruce was their reward.

But Hughes had the last laugh. He voted for the Opposition to defeat the Bruce-Page government and cause the 1929 Federal election.

Again the Labor Party was in office. The last time destroyed by Hughes, now, because of Hughes, in office on the eve of a terrible Depression.

Powerful Drama

So Hughes after being tossed as Prime Minister still enjoyed the powerful drama of making and breaking parties and governments.

However, as Horne points out, he was also regarded not as a great leader (as Hughes imagined himself) but as some comical clown: hardly the reputation that Hughes craved for.

For the rest of his life he got both his reward and his punishment wherever he went. He would be recognised, and by those who loved the memories of the war, he would be acclaimed, but even if in his deafness he might only see their lips moving, he would know they were not acclaiming W.M. Hughes, architect of war and peace.

They were acclaiming a clown like themselves. ‘Look!’, they would say, ‘there’s Billy Hughes! Good day, Billy! Eh, good day Billy!’

Postscript (2015)

I wrote this (slight) review to accompany a brief biography of Horne, who led a few classes in my Honours year in 1976 in Political Science at the University of NSW.