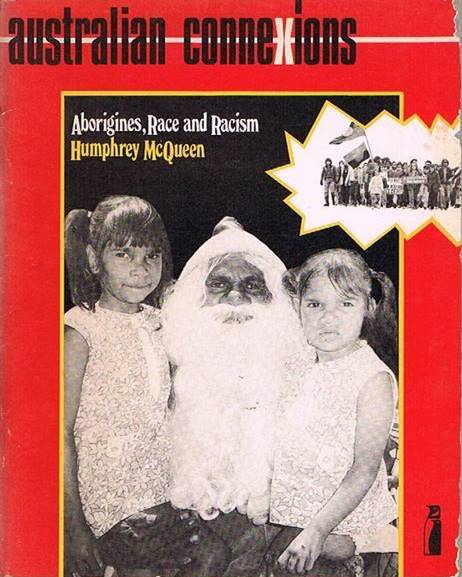

Review of book by Humphrey McQueen under the same title published in Alpha, journal of the St. George Young Labor Association, October 1974, pp. 6-7.

This is a beautifully illustrated book which draws extracts from a variety of authors. Two quotes well demonstrate the corrosive, the destructive, aspects of European colonisation:

Unnatural affection, child-murder, incest and the violation of the sanctity of dead bodies – when one reads such a list of charges against any tribe or nation, either in ancient or modern times, one can hardly help concluding that somebody wanted to annex their land.

– Professor Gilbert Murray, [1911], page 7

If an Aboriginal baby is born today:

It has a much better than average chance of being dead within two years.

If it does survive it has a much better than average chance of suffering sub-standard nutrition to a degree likely to permanently handicap it (a) in its physical and mental potential; and (b) in its resistance to disease.

It is likely in its childhood years to suffer from a wide range of diseases but particularly ear, nose and throat diseases, and respiratory infections.

If it reaches the teen ages, it is likely to be ignorant of and lacking in sound hygienic habits, without vocational training, unemployed, maladjusted, and hostile to society.

If it reaches adult age it is likely to be lethargic, irresponsible and, above all, poverty stricken – unable to break out of the iron cycle of poverty, ignorance, malnutrition, ill-health, social isolation, and antagonism. If it lives in the north it has a good chance of being maimed by leprosy and, wherever its search for affection and companionship may well end in the misert of veneral disease.

If it happens to be a girl, it is likely to conceive a baby at an age when its white contemporary is screaming adulation at some pop star, and will continue to bear babies every twelve or eighteen months until she reaches double figures or dies of exhaustion.

And so the wheel turns…

– Dr H.C. Coombs, 1969, page 46

McQueen’s book explores the present situation of exploitation and government paternalism and also examines the history of prejudice and genocide which has characterised race relations in this country.

The agony of the Aboriginal may will be illustrated by these words: “Mardja amori boaraja Ngu borngya amori mordja” (he who has lost his dreaming is lost).

It would be a stupid and tragic mistake to suffocate, to destroy the rich Aboriginal culture developed around ‘The Dreaming’.

Postscript (2017)

I am grateful to Jim Pearce and Sharon Bond, two former associates from St George Young Labor Association (YLA), for digging up an old copy of this journal.

My brother Shane and I first joined the ALP Branch at Beverly Hills in Sydney in late 1973 or, by the time we were admitted, early in 1974. Joining took a few months or more. We knew no one in the ALP. The process was that after checking for the number in the phone book, you called the ALP head office, requested a membership form, which was then posted out, you filled it in, posted it back, eventually to receive a reply advising that you had been allocated an ALP branch to turn up to. The letter I received advised the name of my local branch, its meeting calendar (first Monday of the month or somesuch) and the physical address for branch meetings. You presented – with the Branch credentials committee (a few of the volunteers) interviewing you. The main questioning was about if you were really Labor, if you had ever supported a non-Labor candidate, or run against an endorsed ALP candidate. It was relatively straight-forward and in our case, as 18 year olds, we were rapidly welcomed to the fold. My brother joined a month or two ahead of me. When he called the ALP, he only asked for one form!

All political parties hope they are appealing to the next generation.

We were invited by the branch secretary to attend the St George Young Labor Association (the Beverly Hills area straddled the St George and Banks electorates. As there was then no Banks Young Labor Association, we were told that the St George Association was the one to belong to.)

We were also invited by the Beverly Hills ALP branch secretary to attend as delegates from the branch to the Annual Conference of Young Labor. We might have been the only members of the branch eligible to attend. There was an age limit. We sat in petrified silence in one of the University of Sydney Law School lecture halls witnessing the event. We were incredibly shy – especially me. Even at university, in my first year, I found it hard in tutorials to speak up. I was terrified of making a fool of myself, very conscious of my speech impediment, and fearful of being laughed at and/or losing my train of thought.

The only way I changed was to force myself to ask a question, to have a stab at making a point, hands sweating, knees weak, face drained of energy. I felt if I spoke early enough, I might overcome the timid reluctance to participate at all. Eventually, over 1974, as my grades improved, through practice and determination to say something in class, my self-esteem slowly grew.

In May 1974, in time for the federal elections, with Michael Lee, we invited Joe Riordan, member for Phillip, to speak to students on the Library lawn. (In those days, outside of the front entrance of the main UNSW Library was the Library lawn where many students ate their lunch. It was an ideal venue for addressing a captive audience.) Joe brought his own audio equipment – microphone, stand, and speakers.

By the end of 1974 a few of the St. George YLA leaders would chat to my brother and I to get a sense of our associations and likely Labor politics. There was not much to discover in those days, beyond dewy-eyed Whitlamism.

At one meeting at St George there was a speaker on possible new abortion legislation and the claim that there needed to be liberalisation. I got up and asked to amend the resolution, saying that I thought we should respect the conscience rights of those who did not support abortion. I self-identified as someone in that camp. The resolution, I vaguely recall, was carried and my amendment defeated. But a few of the Young Labor Left there said they respected me for speaking my mind, and some commented that if my amendment was slightly better worded, they could have supported it. (I am not sure if that was true. But looking back, they were trying to cultivate me to join the Left. There was a lot of anti-Head Office rhetoric and claims that the party machine was corrupt and unprincipled. I was finding my bearings.)

Jim Pearce, a romantic IRA-supporter, lawyer and leftwing civil libertarian, was the leader of the St George YLA group. Within the NSW Left in the St George-Sutherland area, the two poles of the faction were centred around Senator Arthur Gietzelt (1920-2014) and Frank Walker (1942-2012). Gietzelt was communist influenced (and probably inspired by that tradition) and saw the world through a Marxist prism. He was a NSW ALP Senator, 1971-1989. Walker was a civil libertarian lawyer, motivated to fight injustice and discrimination. He was a NSW state MP, 1971-1988, and federal MP, 1990-1996. Both became ministers in Labor governments. At one meeting of the local Steering Committee (the Combined Unions and Labor Steering Committee, to give its full name) Walker wanted to get the numbers. (I completely forget on what issue.) Pearce invited Shane and I to attend. He wanted to help Walker with the numbers. It sounded like an upgrade to a bigger group and an opportunity to better understand the ALP. Afterwards, we were told we were now members of the NSW ALP Left.

In early 1975, we were proposed as candidates for the Young Labor ticket. I was No. 14 out of the 15 to be elected. The Trotskyist elements in Young Labor objected to me, claiming that I was a member of the Festival of Light! The Festival of Light (FoL) was a conservative Christian group founded in the early 1970s by the Rev. Lance Shilton and evangelical supporters, who were concerned by ‘permissive’ tendencies in, and lack sexual morality of, modern Australian society. I was never remotely involved with them. One of the Trots had witnessed my ‘performance’ at St George YLA on abortion and thought this was an issue to win support and fracture the Left.

So, the Trots ran their own ticket against the ‘official’ Left’s ticket. The NSW ALP Right, for the second year in a row, boycotted the NSW Young Labor conference. The only people who turned up at the 1975 conference were from the left. I was elected, with one Trot securing a place, under the proportional representation voting system. Had the ALP Right ran candidates and turned up, as expected, I would have been defeated.

Therefore, in 1975 I was immersed in ALP politics and developed a deeper appreciation for people, traditions, and policy. The result, eventually, as I mulled over everything, was to have severe doubts about the Left, their careless criticisms of Whitlam, seen by many of them as too conservative and close to the Americans. Reading George Orwell, attending Russian politics lectures by George Shipp at UNSW, reflecting on arguments by Owen Harries on foreign policy, were shaping my thinking. Conservatism did not appeal (even if some of my teachers were inclined in that direction.) I did not think I belonged to the Left. Before and after Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese on 30 April 1975, I attended meetings of students at UNSW which urged the Whitlam Labor government to accept Vietnamese refugees, then pouring out of the country. I thought that cause was right. Most of my Left friends thought otherwise.