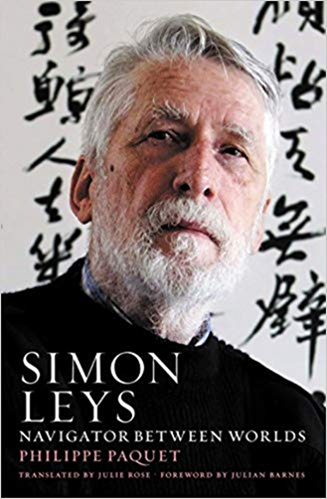

Review: Philippe Paquet’s Simon Leys Navigator Between Worlds, La Trobe University Press/Black Inc. Books, Carlton, 2017, published in the Australian Financial Review, 27 October 2017.

Philippe Paquet’s Simon Leys Navigator Between Worlds is the first book length biography of the author, sinologist, and critic Pierre Ryckmans (1935-2014) who published under the pseudonym Simon Leys. A splendid achievement, on literary, philosophical, historical, and interpretative perspectives, this is arguably the finest ever account of any Australian.

Simon Leys (the name under which he was mostly published) was a China scholar, calligrapher, painter, expert on Chinese and European painting, polemicist, essayist in French and English, translator (Chinese to French and to English; fluent in all three languages), mariner and lover of the sea and its literature, academic, freelancer, husband, father, parent, grandparent, correspondent and friend to many. He saw himself, in an adaption of Isaac Newton’s line, as “a dwarf perched on the shoulders of giants”.

It is difficult to convey coherently the account of a man who, in his range of interests, accomplishments and writings, mocked Walt Whitman’s idea of a person containing “multitudes”. Even the most accomplished must seem much more one-dimensional by comparison. In a book of quotations, Other People’s Thoughts (2007), Leys cites Ralph Waldo Emerson as saying “geniuses have the shortest biographies because their inner lives are led out of sight and earshot; and in the end, their cousins can tell you nothing about them.” Leys might as well have been describing his intensely private, Catholic self.

Luckily the biographer sought guidance in the writing of his account as before he died Leys read and commented on several drafts, though not the final product. In several footnotes and felicitous turns of phrase one can hear the voice of the original. Paquet understands the man, the intellectual, the joi de vivre of what the English novelist Julian Barnes in the Foreword describes as Ryckmans’ “daring, darting and capacious mind.”

And what a mind! Consider his output. Translations into French of writings by the Chinese writer of the Qing Dynasty, best known for the autobiographical Six Years of a Floating Life, Shen Fu (1966); the Sichuan-origin Chinese author, poet, historian, archaeologist, and government official Guo Murou (1970); the great 20th century writer best known for The True Story of Ah Q, Lu Xun (1975); the biography of an artist, The Life and Work of Su Renshan: Rebel, Painter and Madman, 1814-1849? (1970); translations into French and English of Confucius’ The Analects (1987 & 1977), the whimsical novella The Death of Napoleon (1986) – co-translated by Leys into English in 1996, numerous essays and book collections in French and English – notably The Angel and the Octopus (1998; 1999) and The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays (2013), as well as the edited two volumes in French on the sea in French literature (2003), and so forth. At least half of his output was translations, often accompanied by detailed footnotes and commentaries – themselves examples of the finest scholarship. He was happiest about his rendering, from English to French, of Richard Henry Dana’s nineteenth century American classic Two Years Before The Mast, the vivid account of the common sailor’s wretched treatment at sea. Both this book and works of Shen Fu (1763-1825) conveyed great insights and literary talent in describing and explaining the lives of common folk.

None of this made him famous. It was his searing account of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, published in 1971 as Les Habits neufs du président Mao, and in English in 1977 as The Chairman’s New Clothes, which captured the attention of serious China watchers and eventually a wider public. This was the first time he published as “Simon Leys” – the combination being a reference to his own name, as the Apostle Peter was also known as Simon Peter, Simeon or Simon, and “Leys” as a tribute to the main character of Victor Segalen’s René Leys (1922), in which a fictional Belgian teenager residing in Peking in the final days of the Qing Dynasty entertains his employer with accounts of the intrigues and conspiracies taking place behind the walls of the imperial palace. Other books where he focused on Chinese contemporary events, with French and English publication dates, were Ombres chinoises (1974), Chinese Shadows (1977); Images brisées (1976), Broken Images (1979); and La Forêt en feu (1983), The Burning Forest (1986).

The latter book began with a fable translated by Leys, from the Chinese scholar Zhou Lianggong, about a flock of wild doves who one day noticed a fire in a forest and flew to a stream to dip their wings and sprinkle water over the burning. They kept returning as the flames flew higher. It seemed to be of no consequence, all their efforts to contain the destruction were futile. But the birds understood they had no choice. They loved that forest and it broke their hearts to see it destroyed. A similar love for China, whatever the lack of practical impact of his writings, motivated Ryckmans.

Born to a renowned francophone Belgian family in Brussels, as a university student he travelled to the Belgian Congo, where an uncle, also Pierre, had served for 12 years to 1946 as Governor General. The young man was appalled by the barbarism of the Europeans with their pathetic prefecture built on the ruins of an African civilisation. Few of the whites were interested in indigenous mores and customs, their music, language or art, and were incurious about anything of local heritage.

Aged 19, starry eyed and hopeful, he travelled to China and fell in love with the language, the people, and the culture. Thereafter he dedicated his life to discerning that one-quarter of humanity. As he later wrote, the Chinese like “no other people on this planet [have] succeeded in constantly maintaining against tremendous odds a more durable and richer set of human virtues in the obstinate fight which we call civilisation.”

His studies and part-time academic appointments included stints in Taiwan and Hong Kong. At one time he lived in the Kowloon squatter area, sharing with three friends a small accommodation they dubbed Wu Yong Tong (the “hall of uselessness”). In 1970 he was appointed to teach Chinese literature at the Australian National University in Canberra, living among the “remote gum-trees running their white nerves into the air” – to employ a phrase from his striking essay on D.H. Lawrence’s novel Kangaroo.

Ryckmans achieved professorial rank (one his students being a future Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd), before moving to the University of Sydney in 1987 and in 1997 to early retirement. He came to write eight tenths of everything he published in his adopted land.

A “succession of strokes of luck and providential encounters” led him to become Simon Leys, initially a name – instead of his own – judiciously adopted for his published, typically provocative, writings on contemporary China to avoid harassment by the Chinese authorities when he returned to China in 1972 for six months as a cultural attaché to the Belgian Embassy. He liked to say that Mao made the polemicist writer Simon Leys and Chang Hanfang, his inspiring, devoted wife whom he met in Taiwan and married in 1964 in Hong Kong, made the scholar Pierre Ryckmans. She encouraged him to delve deeper into Chinese culture and literature and his books were dedicated to her.

What was striking about this devotee of Chinese art and literature is that he quickly perceived the truth about China’s political structure, better than the so-called political experts. Receiving scraps of information from Chinese language publications, including contemporary newspapers, from chance encounters with Chinese folk, including refugees, from the monitoring of local events by the Hong Kong-based, Hungarian-born Jesuit László Ladány, whose China News Analysis brought news of the real China to a sceptical world, from discussions and debates with Chinese academic colleagues, he recognised that the Cultural Revolution was a kind of macabre power struggle. His analysis was sparkling, clear, and insightful, always expressed in memorable and beautiful prose.

For example, describing the hotel for foreigners in Tientsin he observed: “This monstrous and gloomy construction, a relic of the imperialist era, is usually empty; an army of idle servants yawns and naps along the corridors. In the high-ceilinged rooms, shadowy even in the middle of the day, the guest has the feeling of a vague presence – as if the previous occupant had hanged himself there. In the gloom, as in a cave, can be heard the crystalline music of a leaking toilet, tinkling that monotonous melody of socialist plumbing which can be heard in all the hotels from Prague to Vladivostok, from Canton to Novosibirsk.”

Sworn enemy of codswallop, devoted to the pursuit of truth, he was becoming more and more the writer Simon Leys. In the early 1970s Ryckmans was still sympathetic to the ideals he felt when first visiting the country in 1955: hopeful about the ideals that led to the Chinese revolution and scathing about the communist party and its murderous leadership.

In blistering language he flailed the idiots enthralled to what he once referred to as “the great Hitlero-Lenino-Stalino-Maoist tradition.” The “melon-headedness of the French intellectual world” repulsed him.

In the mid-1970s, Leys noted that the incense bearers of Maoism could be divided between the goats and the smart ones – the latter alert to the zig zags of party ideology and the shifting ranking, snakes and ladders standing, of the leading cadres. With the goats, “heads lowered”, obliviously they “continue to charge down the same road without seeing the signals announcing dangerous bends: and this leads them regularly to find themselves completely bamboozled amidst unforeseen pastures.” When in 1976 one pro-Maoist Le Monde correspondent, with the unfortunate name of Boucs, pleaded he needed a few weeks to see clearly the consequences of Madame Mao’s fall together with her allies in “the Gang of Four”, Leys declared he was ready to wait even a few decades if that was the price to pay “for having the privilege of observing this unheard-of miracle: a Bouc [goat] who finally saw clearly.”

So many of the Mao-soaked Left just moved on, barely even embarrassed, never apologising. He hated fad-masters. In a private letter he wrote in 1978: “we see now that China and the Chinese – that never interested these people; it was just a toy they had fun with for a season, to propel themselves into the rostrums of Paris – full stop!”

Leys always regarded himself as an amateur in politics and so much else. Of Orwell his description is revealing: “[h]e was true and clean; the writer and the man were one – and in this respect, he was the exact opposite of a homme de lettres.”

Thoughtful, liberal in the classic sense, he began his novella The Death of Napoleon with a very Catholic quote from Paul Valery’s Mauvaises Pansies et Autres: “What a pity to see a mind as great as Napoleon’s devoted to trivial things such as empires, historic events, the thundering of cannons and of men; he believed in glory, in posterity, in Caesar; nations in turmoil and other trifles absorbed all his attention… How could he fail to see that what really mattered was something else entirely?” More successful in English than in French, its publication made him realise “the book’s affinity with the anglophone literary sensibility was real and profound” and thereafter he felt completely at ease writing in either language.

As a scholar Ryckmans commented that the highest achievement is “to be able to stimulate in our audience a love for literature, and to make them discover good and beautiful books.” But in the utilitarian late 1990s that task was proving to be more difficult. When he read in an internal university review a missive from the vice chancellor of the University of Sydney imploring the academic staff to think of students as “customers” he knew it was time to go. He chose to see the next phase of his life as jubilación, to utilise that Spanish word ordinarily and inadequately translated as “retirement”.

Never embarrassed by his Belgian-Australian identity, he defiantly wrote: “…it’s the fact of being born in a major country that tends to make you provincial, because you then run the risk of assuming that the nation’s culture is enough, whereas the citizens of a culturally marginal nation will be keen to look elsewhere, to learn foreign languages and discover the world…”

Paquet in 551 pages plus nearly a hundred in notes has written a biography that never fails to interest. It is enjoyable to find an author who so well appreciates his subject and along the way conveys a sure, critical and writerly understanding of the man and his importance. First published in French by Gallimard last year, the translation by Julie Rose is exceptional. Morry Schwartz, the publisher, who has long championed Leys’ writings, deserves mention for bringing this work to an English-language audience.

Ryckmans had not the slightest interest in fame. Rarely heard on radio, almost never on television, he boycotted writers’ festivals and fairs preferring his books speak for themselves. But sometimes he consented to interviews, preferring written responses to specific questions. He loved to paint, believing the brush to be the seismograph of the mind.

We still feel the tremors.

Note on Publication:

Michael Easson first met Pierre Ryckmans in 1989 when, at the invitation of Professor Stephen Fitzgerald, they both spoke at a public event at the University of Sydney on the significance and consequences of the Tiananmen Square massacres.

Below are several letters in the spidery, neat handwriting of Pierre Ryckmans. (Not published with the original article.)