Published online in the Australian Financial Review, 15 July 2025.

The IHRA definition does no more than recognise that anti-Zionism may or may not be antisemitic in its motivation or effects. It nearly always depends on how points are made, content and context.

Of course, political criticism of Israel is legitimate, even warranted, sometimes. But antisemitism, a term for anti-Jewish racism and hatred is not. That is at the heart of Australia’s Antisemitism Envoy’s, Jillian Segal’s, call for effective education, monitoring and management of those who overstep the mark.

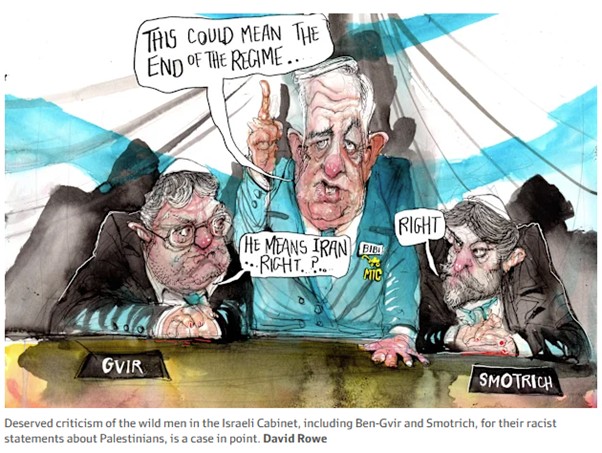

In Australia, criticism of Israel is commonplace. Deserved criticism of the wild men in the Israeli Cabinet, including Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, for their racist statements about Palestinians, is a case in point.

But some demonstrations are violent, filled with loathing for Jews. When that happens, it is antisemitism. Clear definitions are needed. Otherwise, we are left only with capricious, subjective judgement fuelled, more often than not, by prejudice and ignorance. That is where the current debate is located.

Naturally, defence of free speech is bundled into the question of limits, definitions, and what are ‘red lines’ as to what is said and done. This article explores the controversy.

In 2021, the Australian government, on a bi-partisan basis, supported the definition of antisemitism adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA): “Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.”

Adopted in May 2016 in Bucharest by Alliance members including governments and community organisations, the stakeholders determined to reach agreement about antisemitic terms.

On the weekend, Defence Industry Minister, Pat Conroy, in his ‘Insiders’ interview reaffirmed Australia’s support for the definition.

Yet some human rights groups, claiming to champion fair, legitimate dissent, say that the definition “conflates” criticism of Israel with antisemitism. Does it?

Here is what the definition itself says: “Manifestations might include the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. However, criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.”

The definition then provides 11 illustrative examples of antisemitism, some relating to Israel, but only on the basis that these “could, taking into account the overall context” amount to antisemitism. It is not automatic. There is no blanket characterisation of any particular set of words as antisemitic. Each case must be assessed in context and on its merits. The “conflation” assertion is thus entirely bogus.

Common sense should tell us that it is as fallacious to argue that political criticism of Israel, or of Zionism as a set of beliefs, can never amount to antisemitism, as it is to argue that such criticism always amounts to antisemitism.

To take an extreme example, the words “F… Israel” spraypainted on the front of a synagogue in Australia are obviously both anti-Zionist and antisemitic. The IHRA definition cites more subtle and insidious examples of where anti-Zionism and antisemitism may coincide.

Commentators who deny the Jewish people their right to self-determination while claiming that very right for Palestinians; or who require Israel to observe standards of behaviour exceeding that to which other democratic nations are held; or who draw comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis; or who hold Jews in Australia collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel, may well be transgressing into antisemitism. Every case must be assessed individually. The actual language used, and the context will be critical.

Kenneth S. Stern is put forward by IHRA’s critics as the “author” of the definition who now disowns his creation. His is an important, legitimate voice. But, in fact, he was neither the sole nor even the principal author; a team of people drafted it, including the former Canadian Attorney-General and human rights lawyer, Irwin Cotler. Stern has not disowned the definition. He is critical of the way that some proponents of the definition distort its meaning in order over-state its effect. One could make an identical criticism of IHRA’s detractors. Stern says the link between antisemitism and anti-Zionism needs to be treated with extreme care. Agreed. He does not say there is no link.

The IHRA definition does no more than recognise that anti-Zionism may or may not be antisemitic in its motivation or effects. It depends on how points are made, content and context. It nearly always does.

The obvious conclusion is that anti-Zionism and antisemitism are neither identical nor mutually exclusive. The relationship between them can be represented by a Venn diagram, with a considerable area of overlap.

Are shouts “from the river to the sea Palestine will be free” antisemitic? If the objective effect is a call for the wholesale destruction or abolition of Israel as a country as opposed to engaging in a political debate regarding its borders and/or the actions of the Israeli government vis a vis Palestinians, then yes, even if the yellers don’t know which sea, which river.

In a case this May before the UK High Court, Justice Chamberlain referenced the IHRA definition and ruled: “If properly understood—i.e., as examples of speech which could, depending on the context, be antisemitic—most of the IHRA’s examples are, in my view, both unobjectionable and useful…It must also be borne in mind that the IHRA’s examples were billed as “contemporary examples” in 2016. They were not intended to set the parameters of legitimate political debate for all time.”

That is the reasonable interpretation of the IHRA examples and of Australia’s Antisemitism Envoy’s call to action.

Postscript (2025):

One person who read my article was David Marr, compere of ABC Radio programme ‘Late Night Live’. Unfortunately,

I got the impression he was not interested in chatting meaningfully.

This is our exchange:

David Marr to Michael Easson, via email, 20 July 2025:

Michael,

Thank you for sending me this. I missed it in the Fin. Very interesting. My question: who is to decide whether this or that criticism of Israel is tainted by antisemitism? Careers and funding will turn on this if the Segal report – or some version of it – is adopted. You make the point several times that the distinction can be subtle: “It nearly always depends on how points are made, content and context.”

So who is to decide? A committee? The courts? The office of the Envoy?

And on whom will be burden of proof fall? Must Israel’s critics prove their criticism is NOT antisemitic? Or will it be up to Israel’s defenders to prove that criticism of, say, the Gaza campaign IS antisemitic? It’s a most important point.

A further question is raised by the IHRA provision that “criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.” What other country do you have in mind? Is there other country that’s conducted anything like Israel’s campaign in Gaza?

I’m keen to explore this further.

David Marr.

I’m cc-ing this to the executive producer of Late Night Live, Jack Schmidt.

Michael Easson to David Marr, via email, 21 July 2025:

David,

Thank you for reading my piece in the Fin last week and raising questions about some implications of the recent report of the Special Envoy’s Plan to Combat Antisemitism.

IHRA & my AFR Article

My piece centred on the argument that the IHRA definition of antisemitism precludes or severely restricts criticism of Israel. My view is that this is not a fair criticism. Undoubtedly, everything turns on content, language, and context.

But criticism of Israel, its actions in Gaza, its treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Territories, the antics of Smotrich & Ben-Gvir and extremists in the government of Israel, the actions of settlers, etc., ought to be subject to robust review and criticism. The IHRA definition does not curtail that.

If, however, someone says: “The Jews are a cruel people. Just look at what they are doing in Gaza wantonly killing civilians” that is at the least borderline antisemitism, by referring to Jews as cruel as a race.

A person who denies the indigenous people of Israel the right to their own state, who claims Israel is a colonialist construct, is appallingly wrong. How the position is put, context and content are at the heart of any assessment of antisemitism. I personally believe the Palestinians too have a connection to the land that should be respected. Hence my support for a two state-solution, the spirit of what the UN tried to resolve in 1947. I do however also understand the counter-factual that, having a Palestinian state which is implacably committed to the destruction of the state of Israel, located on Israel’s borders, is a solution fraught with difficulty.

Regarding antisemitism, you ask ‘who is to decide’ on boundaries and breaches.

Before going there, let me comment that another point of my article was to say the IHRA definition was not born an orphan. I remember my late friend Jeremy Jones telling me about the IHRA debates. He was one of the many authors of the ultimate draft in Budapest in 2016. More than twenty years ago, Stern, as director of the antisemitism division for the American Jewish Committee, led the move to draft something. Stern is sometimes referred to as principal IHRA author (Guardian, SMH, elsewhere), but that exaggerates. The former Canadian Attorney General, Irwin Cotler, was influential in the penultimate document’s wording. Stern’s is an important voice in the discussion. He hasn’t disowned his work. He warns about weaponising IHRA examples to deny sovereignty and agency to Palestinians. I agree. That is not in accordance with what the IHRA means or, for that matter, what the Special Envoy is advocating.

All that is the context of why I wrote my piece last week.

Who Decides Turns on the Problem to be Addressed

I have no brief to represent the Special Envoy. I had no role in her document’s drafting. But it reads well to me as a position statement about the problems to be addressed.

I read the document as a call for governments, education and media institutions, as well as the public, to commit resources and action to addressing a dreadful problem.

Her report says: “Antisemitism erodes and is contrary to values that define Australia: fairness, freedom and mutual respect. It is a hatred that manifests in harmful words, and can lead to violent deeds, undermining the basic right to live free of discrimination and hate, and attacking the very foundations of a thriving democracy. As such, it poses a threat not just to Jewish Australians, but to our entire nation.”

The Envoy’s report notes that the recent flaring of hatreds has not occurred in a vacuum: Since October 7th: “This has been driven by conflict in the Middle East, manipulated narratives in the legacy media and social media and the spread of extremist ideologies. Ancient myths and misinformation have re-emerged in new forms to justify violence and threats against the Australian Jewish community. …From hate-filled chants outside the Sydney Opera House, preventing others attending the site, to the firebombing of a Melbourne synagogue, we are shown what happens when hate is left unchecked.”

There is a real and live challenge. As Conor Cruise O’Brien once wrote: Antisemitism is a light sleeper.

It has roared to life.

What to Do

Accepting that there is a problem requires evaluation of what to do.

Any actions need to have regard for and respect the values of freedom of speech and fair play. Australian Parliaments, Federal and states, have recognised that these are not unfettered rights. Hence, hate speech legislation.

In this, I am with John Stuart Mill’s liberal notion of the harm principle: People should be free to act however they wish unless their actions cause harm to somebody else. Incitement to violence, racial vilification, and other manifestations of hate, are red lines.

You write:

My question: who is to decide whether this or that criticism of Israel is tainted by antisemitism? Careers and funding will turn on this if the Segal report – or some version of it – is adopted. You make the point several times that the distinction can be subtle: “It nearly always depends on how points are made, content and context.”

So who is to decide? A committee? The courts? The office of the Envoy?

Let me answer this set of questions with another set. Who adjudicates complaints of antisemitism now? Based on what criteria? Who bears the onus of proof, and as more evidence comes to light concerning any allegation of antisemitism, at what point does the onus shift?

Early last year, I wrote to one university’s Chancellor & Vice Chancellor, pointing out that one of their professors posted on his X account the flags of Hamas on October 8th and I noted that a European university to which this person was affiliated asked that he show cause as to why he should not be suspended. He resigned. But is still at large.

Also last year, I noticed an academic posted that universities should not be “safe places for Zionists.” I wrote to that university’s Chancellor and Vice Chancellor what they intended to do.

In other instances, the flags of Hamas and Hezbollah, two terrorist organisations proscribed by the Australian government, are seen regularly fluttering at university campuses.

Little to nothing has been done.

No wonder many Jewish students and academics do not feel safe.

In 2024, the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee conducted an inquiry into whether to hold a judicial Inquiry into antisemitism at Australian universities reported on 4 October 2024 and among its conclusions stated:

2.253 It is clear to the committee that university responses to incidents of antisemitism, and the fears of Jewish students and staff, have been woefully inadequate. The committee considers that the universities’ responses to this issue are remarkably similar to their historically poor responses to sexual assault and harassment.

A majority of the Committee members (i.e., ALP and Greens Senators) decided not to recommend a judicial Inquiry and instead referred the matter for further Inquiry to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, which in turn handed down its report on 12 February 2025.

Here, there was bipartisan agreement between the Government and Opposition for a range of measures which are consistent with those supported by the Special Envoy, including:

- Australian universities adopt a definition of antisemitism that “closely aligns” with the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition

- Australian universities should report on the outcome of complaints with greater transparency, including input from vice-chancellors.

- The government consider whether it needs to amend the Fair Work Act to enable disciplinary or “other action” be taken in relation to employees or ARC grantees that have breached the Criminal Code or Racial Discrimination Act.

- Australian universities review and simplify their complaints procedures, including publishing regular de-identified reports of complaints received.

- Universities deliver ongoing training to students, staff and leadership on recognising and addressing antisemitism.

- The government consider expanding the compliance powers of the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency on student wellbeing and safety.

- The National Student Ombudsman review university practices to reduce antisemitism on campuses within 12 months.

- The government give consideration to a judicial inquiry if the response by universities has been insufficient.

Since that Parliamentary report was issued, the Go8 and Universities Australia (UA) adopted a version of the IHRA Working Definition, so that is the measure they themselves adopted. A complainant bears the onus of proving the facts on which the complaint is based. If the facts, taken in their overall context, are assessed as meeting the Go8/UA definition, the onus shifts to the respondent.

On 25 February 2025 a media release from UA stated that its 39 members unanimously endorsed the following working definition of antisemitism:

“Antisemitism is discrimination, prejudice, harassment, exclusion, vilification, intimidation or violence that impedes Jews’ ability to participate as equals in educational, political, religious, cultural, economic or social life. It can manifest in a range of ways including negative, dehumanising, or stereotypical narratives about Jews. Further, it includes hate speech, epithets, caricatures, stereotypes, tropes, Holocaust denial, and antisemitic symbols. Targeting Jews based on their Jewish identities alone is discriminatory and antisemitic.

“Criticism of the policies and practices of the Israeli government or state is not in and of itself antisemitic. However, criticism of Israel can be antisemitic when it is grounded in harmful tropes, stereotypes or assumptions and when it calls for the elimination of the State of Israel or all Jews or when it holds Jewish individuals or communities responsible for Israel’s actions. It can be antisemitic to make assumptions about what Jewish individuals think based only on the fact that they are Jewish.

“All peoples, including Jews, have the right to self-determination. For most, but not all Jewish Australians, Zionism is a core part of their Jewish identity. Substituting the word “Zionist’’ for ‘’Jew’’ does not eliminate the possibility of speech being antisemitic.”

So, in relation to universities, the answer to your first set of questions is that the universities themselves indicated their unfitness to self-regulate in the absence of guidelines and position statements.

Related to this, I suspect that the people charged with protecting students from antisemitism have had only the dimmest understanding of that phenomenon and, perhaps, even less sensitivity to it. They need education and training, and fall-back scrutiny is needed by the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency and The National Student Ombudsman.

Even so, the people who staff these two bodies might not have had real-life experience of antisemitism and may be no more capable of recognising and effectively countering antisemitism than the universities they oversee.

What then? Nobody suggests that funding sanctions should be a first resort, but unless there is some ultimate sanction with teeth, nothing will change.

Acknowledging this challenge, the universities stated: “UA will provide this definition to TEQSA and request that it works with the HESP to best determine the positioning of the definition within the Higher Education Standards Framework, and to ensure it acknowledges universities’ responsibility to honouring academic freedom of speech and expression.”

Who decides when the sanction point is reached? The Special Envoy can make recommendations but, ultimately has no power other than the power of persuasion. It is the elected government and its agencies to decide.

Israel Criticism

You ask, legitimately, as it is important to know:

Must Israel’s critics prove their criticism is NOT antisemitic? Or will it be up to Israel’s defenders to prove that criticism of, say, the Gaza campaign IS antisemitic? It’s a most important point.

A further question is raised by the IHRA provision that “criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.” What other country do you have in mind? Is there other country that’s conducted anything like Israel’s campaign in Gaza?

I’m keen to explore this further.

Hopefully, I have indicated already that robust criticism of Israel for its conduct of the war is fair game.

You ask: “Is there other country that’s conducted anything like Israel’s campaign in Gaza?” Sadly, yes. Although no two wars are exactly the same, Israel’s actions in Gaza have resulted in a lower percentage of civilian deaths (about 60% based on 22,000 Hamas terrorists killed out of the total deaths in Gaza, of which we do not have an accurate picture (though Hamas claims around 57,000) than the actions of other western military forces in recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (about 90% according to the UN). Despite various, vigorous claims, there is no accurate estimate of civilian casualties caused by the IDF. Andrew Fox at the Centre for New Middle East and others have picked apart Hamas supplied figures and their demographic breakdown. Even if it was as low as 20,000 uninvolved civilians, it is still shocking. The precautions in this conflict by the IDF, I hope and trust, will stand up to scrutiny at war’s end. Time will tell.

I know from conversations with Mike Kelly, the former Labor MP, that our own ADF was heavily involved in the campaign to defeat Al Qaeda in Iraq, including the devastating siege of Fallujah, and then to defeat ISIS. In the siege of Mosul, against around 12,000 ISIS terrorists, the battle lasted 9 months from October 2016 to July 2017. ADF assets were in engaged in the bombing effort and in coordinating the coalition air campaign in general through our Wedgetail aircraft. This resulted in the flattening of over 40,000 buildings, including 47 mosques. Hospitals were also destroyed when their protected status was compromised. The siege of Mosul was of comparable scale to Gaza in terms of the urban terrain and civil population. It is estimated that around 10,000 civilians were killed. In Mosul, there was none of the 500km of sophisticated underground military infrastructure, capability and 17 years of preparation that faced Israel in Gaza. The ADF and Coalition forces were also not facing the 50,000-60,000 enemy of all factions that Israel has had to fight in Gaza.

Israel’s actions need also to be considered in light of the open declaration by Yayha Sinwar that Hamas regards Palestinian civilians as “necessary sacrifices” in Hamas’s war of extermination against Israel.

What has been unfolding in the Middle East over the last 21 months is a terrible war which Israel did not start, did not want and did not expect. Prior to October 7th, a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas had been in effect for 2 years. Through its agency known as COGAT, Israel was facilitating the delivery of large quantities of food, medical supplies and other materials into Gaza every day. Gazans who needed highly specialised medical treatment (including Hamas family members) were entering Israel and being treated free of charge by Israeli doctors in Israeli hospitals. Several thousand Gazans travelled to work in Israel each day and received the same pay and conditions as Israeli workers. There were leaked news reports of secret meetings between Israeli and Saudi officials to hammer out a comprehensive regional peace, including a two-State outcome to the conflict.

We now know from captured Hamas documents that Hamas broke the ceasefire and started the war on October 7 precisely for the purpose of torpedoing the moves towards peace (see first attachment). That would help explain why the October 7 attacks mostly targeted civilian population centres and were carried out with unimaginable ferocity. Hamas and its supporters gunned down civilians in the streets, in their homes and at an outdoor concert, beheaded some of the victims, burned children alive, raped women next to their dead friends’ bodies, and kidnapped 251 Israelis and foreign nationals (including babies and Holocaust survivors), parading some of them as trophies through the streets of Gaza to baying crowds. The intentionality was clear and admitted to. The attacks left just under 1200 people dead, resulting in the largest massacre of Jews in a single day since the Holocaust.

Hamas leaders openly declared that further such attacks would be launched repeatedly until Israel and its Jewish population were destroyed. Hezbollah and Iran were in on the plan and approved it five days’ earlier (Captured Hamas documents show that Hamas started war with Israel on October 7, 2023 in order to derail Saudi-Israel peace deal). They share Hamas’s openly declared genocidal goals. A two-state outcome and regional peace is the last thing they want. In fact, through the war, Israel faced attacks from seven directions, all orchestrated by Iran and almost entirely under their effective control, which constitutes the war crime of aggression as spelled out in Article 8bis (g) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. (This reads: “The sending by or on behalf of a State of armed bands, groups, irregulars or mercenaries, which carry out acts of armed force against another State of such gravity as to amount to the acts listed above, or its substantial involvement therein.” (See: Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court at p.11).

In the immediate aftermath of the Hamas attacks, one might have expected statements of condemnation from our intellectual elites, including at our universities. Instead, there was mainly just silence, broken only by mendacious attempts to justify Hamas’s actions. This has only worsened as the war has continued.

My conclusion is that Israel’s legal and moral right to defend itself in the circumstances outlined is beyond dispute. Just war theory differentiates between Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello. There is understandably debate in this war, as in any war, about how far a nation can legitimately go in defending itself, even in a just war. International law imposes clear limits. Despite the heart-wrenching images that the media presents to us, Israel has observed those limits to a far greater extent than have other western military forces fighting in comparable wars in recent years, such as in Mosul in Iraq, uprooting ISIS, and in Afghanistan. (The Israel-Hamas War: Self Defense, Necessity and Proportionality). Those were wars in which Australia participated.

The IDF has provided advance notice by text messages and leaflets directly to civilians of impending attacks on Hamas posts, has designated safe areas for civilians, allowed for humanitarian corridors to supply civilians during fighting, and so on. This has not been perfect – how could it be. It’s war and, I repeat, a war Israel did not start, did not want and did not expect. Many thousands of innocent people have tragically been killed. Hamas has deliberately used civilians and civilian structures for cover.

All civilian casualties in war are to be deplored. Some 600,000 German civilians died in the Allied bombing of German cities during WWII. In the Normandy campaign, the cities of Cherbourg and Caen were flattened, and 20,000 French civilians were killed, where the Allies included Free French forces inflicting this damage. It is interesting that the Normandy campaign began on the scale of the war in Gaza. The Allies faced 50,000 Nazi troops at the landing. No-one would seek to justify the loss of innocent lives, regardless of whether any of those civilians were Nazi supporters or sympathisers. But I do not place the primary responsibility for their deaths and suffering on the Allies. I place it squarely on the Nazi regime which planned and started and continued the war. Similarly, I place the primary responsibility for the deplorable civilian deaths and suffering in Gaza squarely on Hamas and the other terrorist gangs which planned and started and continued the war, till today. Every death, directly and indirectly, is due to Hamas.

I don’t claim that this absolves Israel of all secondary responsibility, but it does provide what I consider a truthful perspective and realistic context.

Israel, independently and robustly, should consider and review its role in detail after the war’s end or following a substantially held ceasefire.

Operation Gideon’s Chariots officially began two months ago on May 16, 2025, when the IDF launched widespread airstrikes and initiated a significant ground manoeuvre in the Gaza Strip. The objectives of the operation were to disarm and remove Hamas from power, and to release the hostages.

Two months later and despite Israel now controlling 75% of the territory in Gaza, it appears neither objective has been achieved, nor do they look close to being achieved. Though we cannot judge that completely. We might know later. Tragically, the remaining Hamas elements are going all out on blowing up the current relief effort. In this two-month period, 55 IDF soldiers have died and more than a hundred have been wounded.

Concluding Point

All this requires a delicate balance.

You are a respected commentator who, I’m sure, is familiar with most of the usual responses.

If you are open to it, I would appreciate us having a coffee to discuss any suggestions for a strategy to counter antisemitism which is targeting all Jews for what is happening in the Middle East. Yet nothing comparable is happening in the sense of targeting Australians of any other heritage be it Russian, Chinese, Sudanese etc., for what is happening in other conflict zones elsewhere in the world. Nor should it.

Yours sincerely,

Michael Easson

David Marr to Michael Easson, via email, 22 July 2025:

Dear Michael,

To be frank, I’m not interested in your defence of Israel. We differ profoundly here but the pros and cons of the Gaza war are not why I responded to your AFR piece. What troubles me are the special rules for public debate which you – and Segal and many others – propose should operate in Australia. And not just here, of course. It’s a world issue.

You don’t have to convince me that antisemitism is a terrible evil. But you and advocates like Segal do have to convince Australians that finding traces of antisemitism in criticism of Israel is enough to punish people and institutions. You give as an example of “borderline antisemitism” the statement: “The Jews are a cruel people. Just look at what they are doing in Gaza wantonly killing civilians.” But in and after WWII, there were Australians saying: “The Japanese are a cruel people. Just look at what they did on the Burma railway.” Perfectly legitimate criticism.

Apart from questions of who and how antisemitism should be identified – questions I don’t think you were able to answer – isn’t the bigger issue here the danger of trivialising antisemitism? It is an old, visible and terrible evil, but you seem to be talking about something so subtle that it lies even outside the extraordinarily broad sweep of s81c of the Racial Discrimination Act.

On a point of fact: David Slucki and his team rejected the HIRA definition. There are very many critics who say the definition accepted by most Australian universities doesn’t solve the problems raised by HIRA. But that was the intention of the drafters. I interviewed David on the show on March 31. He’s very interesting.

I respect your argument that other nations – ours, for instance – have lately been involved in destructive wars that caused a great many civilian casualties. We didn’t, however, set about the deliberate starvation of a civilian population. Starving children is a bit hard to justify these days as I think your silence on the point acknowledges.

I am curious about your remark that the academic who showed the Hamas flag on Oct 8 “is still at large”. Are you arguing for a prison sentence here?

All the best,

David.