Published in Labor Leader, Vol. 4, No.4, December 1980, pp 4-5.

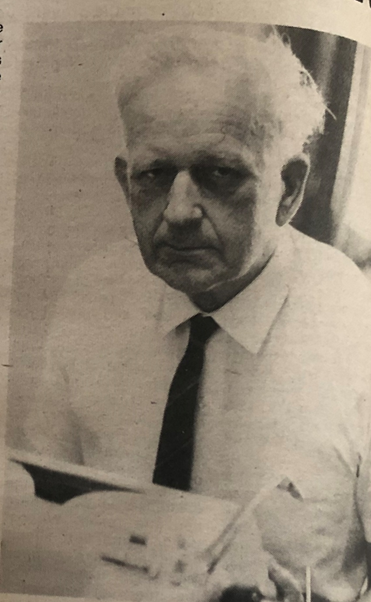

Nearing retirement, Rupert Lockwood plans several books linking the history of his times with his own experiences, ranging from childhood in a German-origin Wimmera community, exclusive private school life at Wesley College, Melbourne – the same school which turned out Robert Gordon Menzies and Harold Holt – to the joining of the Communist Party in 1939, the Petrov Royal Commission, and a three year stint as Tribune correspondent in Moscow.

In 1928, as the Great Depression broke, Lockwood landed a job as a cadet journalist with the Melbourne Herald. He was the only cadet who was not the son of a famous father.

Lockwood attributes his success to the fact that his elder brother, a naval surgeon, later Rear-Admiral Lionel Lockwood, MVO OSC, MD and later Honorary Surgeon to Queen Elizabeth II, played golf with the Herald editor.

Rupert Lockwood was soon unemployment rounds man for the Herald, visiting hostels and camps for the jobless and homeless. Among them was the Broadmeadows military camp where the unemployed were clothed in surplus uniforms left over from the Great War. The uniforms were dyed dark blue so they would not be reminded of the Khaki many of them donned on promise of returning to a land fit for heroes.

In the early thirties Lockwood’s radical political views were being formed. In this Depression era of great suffering, Lockwood had experience of the paranoia of the establishment. Though the unemployed were generally non-rebellious and demoralised by their privations, many business and military leaders looked under their beds for revolutionaries. Private armies such as the New Guard were formed. On several occasions mobilisation alerts were issued by these private armies when unemployed marches were held in Melbourne.

Fellow Travelling

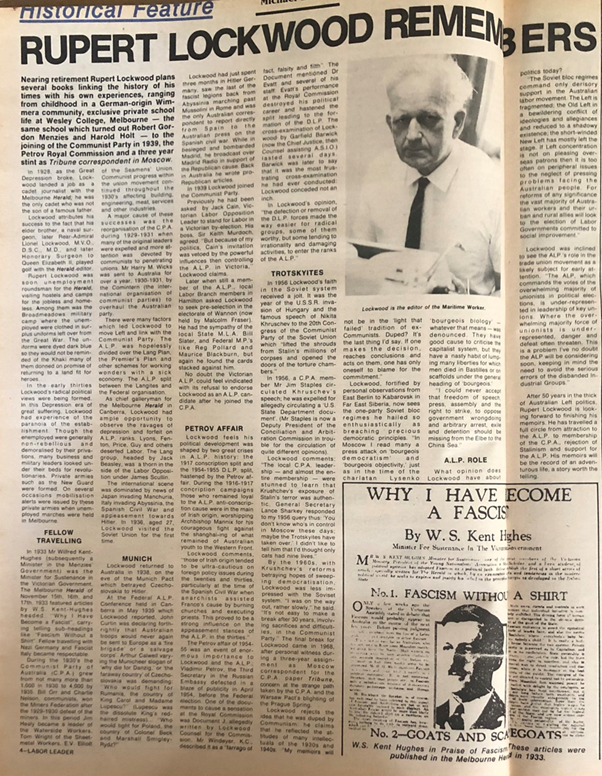

In 1933 Mr. Wilfred Kent Hughes (subsequently a Minister in the Menzies government) was the Minister for Sustenance in the Victorian government. The Melbourne Herald of November 15th, 16th, and 17th, 1933 featured articles by W.S. Kent Hughes headed: ‘Why I Have Become a Fascist’, carrying telling sub-headings like ‘Fascism Without a Shirt’. Fellow travelling with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy became respectable.

During the 1930s the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) grew from not many more than 1,000 in 1930 to 4,000 by 1935. Bill Orr and Charlie Nelson, communists, won the Miners’ Federation after the 1929-1930 defeat of the miners. In this period Jim Healy became a leader of the Waterside Workers, Tom Wright of the Sheet Metal Workers, Elliot V. Elliot of the Seamen’s Union. Communist progress within the union movement continued throughout the 1930s, affecting building, engineering, meat, services and other industries.

A major cause of these successes was the re-organisation of the CPA after 1929-1931, when many of the original leaders were expelled, and more attention was devoted by communists to penetrating unions. Mr Harry M. Wicks was sent to Australia for over a year, 1930-1931, by the Comintern (the international organisation of communist parties [run by Moscow]) to overhaul the Australian party.

There were many factors which led Lockwood to move Left and link with the Communist Party. The ALP was hopelessly divided over the Lang Plan, the Premiers’ Plan and other schemes for working wonders with a sick economy. The ALP split between the Langites and the Federal organisation.

As chief galleryman tor the Melbourne Herald in Canberra, Lockwood had ample opportunity to observe the ravages of depression and forfeit on ALP ranks. Lyons, Fenton, Price, Guy and others deserted Labor. The Lang group, headed by Jack Beasley was a thorn in the side of the Labor Opposition under James Scullin.

The international scene was dominated by news of Japan invading Manchuria, Italy invading Abyssinia, the Spanish Civil War and appeasement towards Hitler. In 1936, aged 27, Lockwood visited the Soviet Union for the first time.

Munich

Lockwood returned to Australia in 1938, on the eve of the Munich Pact which betrayed Czechoslovakia to Hitler.

At the Federal ALP Conference held in Canberra on May 1939 which Lockwood reported, John Curtin was declaring forthrightly that Australian troops would never again be sent to Europe as a ‘fire brigade’ or a ‘salvage corps’. Arthur Calwell varying the Municheer slogan of ‘why die for Danzig?’ or ‘the faraway country’ of Czechoslovakia was demanding: “Who would fight for Rumania, the country of King Carol and Madame Lupescu? [Lupescu was the dissolute King’s red-haired mistress]… Who would fight for Poland, the country of Colonel Beck and Marshall Smigley-Rydz?”

Lockwood had just spent three months in Hitler Germany, saw the last of the fascist legions back from Abyssinia marching past Mussolini in Rome, and was the only Australian correspondent to report directly from Spain to the Australian press on the Spanish civil war. While in besieged and bombarded Madrid, he broadcast over Madrid Radio in support of the Republican cause. Back in Australia he wrote pro Republican articles.

In 1939 Lockwood joined the Communist Party.

Previously he had been asked by Jack Cain, Victorian Labor Opposition Leader to stand for Labor in a Victorian by-election. His boss, Sir Keith Murdoch, agreed. “But because of my politics, Cain’s invitation was vetoed by the powerful influences then controlling the ALP in Victoria,” Lockwood claims.

Later when still a member of the ALP, local Labor Branch members in Hamilton asked Lockwood to seek pre-selection In the electorate of Wannon (now held by Malcolm Fraser). He had the sympathy of the local State MLA Bill Slater and Federal MPs like Reg Pollard and Maurice Blackburn, but again he found the cards stacked against him.

No doubt the Victorian ALP could feel vindicated with its refusal to endorse Lockwood as an ALP candidate alter he joined the CPA.

Petrov Affair

Lockwood feels his political development was shaped by two great crises in ALP history: the 1917 conscription split and the 1954-1955 DLP split, hastened by the Petrov affair. During the 1916-1917 conscription campaigns, those who remained loyal to the ALP anti-conscription cause were in the main of Irish origin, worshipping Archbishop Mannix for his courageous fight against the shanghai-ing of what remained of Australian youth to the Western Front.

Lockwood comments: “Those of Irish origin tended to be ultra-cautious on foreign policy issues during the twenties and thirties, particularly at the time of the Spanish Civil War when anarchists assisted Franco’s cause by burning churches and executing priests. This proved to be a strong influence on the appeasement stances of the ALP in the thirties.”

The Petrov affair of 1954-55 was an event of enormous importance to Lockwood and the ALP. Vladimir Petrov, the Third Secretary in the Russian Embassy, defected in a blaze of publicity in April 1954, before the Federal election. One of the documents to cause a sensation at the [subsequent] Royal Commission was Document J, allegedly written by Lockwood. Counsel for the Commission, Mr Windeyer KC, described it as a “farrago of fact, falsity and filth.” [The document was an account, drawn from direct sources, of goings on in ALP politics, written for someone in the Soviet Embassy.] The Document mentioned Dr Evatt and several of his staff.

Evatt’s performance at the Royal Commission destroyed his political career and hastened the split leading to the formation of the DLP. The cross-examination of Lockwood by Garfield Barwick (now the Chief Justice, then Counsel assisting ASIO) lasted several days. Barwick was later to say that it was the most frustating cross-examination he had ever conducted: Lockwood conceded not an inch.

In Lockwood’s opinion “the defection or removal of the DLP forces made the way easier for radical groups, some of them worthy, but some tending to irrationality and damaging activities, to enter the ranks of the ALP.”

Trotskyites

In 1956 Lockwood’s faith in the Soviet system received a jolt. It was the year of the USSR invasion of Hungary and the famous speech of Nikita Khrushchev to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union which “lifted the shrouds from Stalin’s millions of corpses and opened the doors of the torture chambers.”

In 1956 a CPA member, Mr Jim Staples, circulated Khrushchev’s speech; he was expelled for allegedly circulating a US State Department document. (Mr Staples is now a Deputy President of the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission, in trouble for the circulation of quite different opinions).

Lockwood comments: “The local CPA leadership – and almost the entire membership – was stunned to learn that Khrushchev’s exposure of Stalin’s terror was authentic. General Secretary Lance Sharkey responded to my 1956 query thus: ‘you don’t know who’s in control in Moscow these days; maybe the Trotskyites have taken over.’ I didn’t like to tell him that I’d thought only cats had nine lives.”

By the 1960s, with Khrushchev’s reforms betraying hopes of sweeping democratisation, Lockwood was less impressed with the Soviet system. “I was on the way out, rather slowly,” he said. “It’s not easy to make a break alter 30 years, involving sacrifices and difficulties in the Communist Party.” The final break for Lockwood came in 1968, after personal witness during a three-year assignment as Moscow correspondent for the CPA paper Tribune, concern at the strange path taken by the CPA and the Warsaw Pact’s blighting of the Prague Spring.

Lockwood rejects the idea that he was duped by communism. He claims that he reflected the attitudes of many intellectuals of the 1930s and 1940s: “My memoirs will not be in the ‘light that failed’ tradition of ex-communists. Duped? It’s the last thing I’d say. If one makes the decision, reaches conclusions and acts on them, one has only oneself to blame for the commitment.”

Lockwood, fortified by personal observations from East Berlin to Khabarovsk in Far East Siberia, now sees the one-party Soviet bloc regimes he hailed so enthusiastically as breaching precious democratic principles. “In Moscow I read many a press attack on ‘bourgeois democratism’ and ‘bourgeois objectivity’, just as in the time of the charlatan Lysenko – ‘bourgeois biology’, whatever that means – was denounced. They have good cause to criticise the capitalist system, but they have a nasty habit of lumping many liberties for which men died in Bastilles or on scaffolds under the general heading of ‘bourgeois’.

“I could never accept that freedom of speech, press, assembly and the right to strike, to oppose government wrongdoing and arbitrary arrest, exile and detention should be missing from the Elbe to the China Sea.”

ALP Role

What opinion does Lockwood have about politics today?

“The Soviet bloc regimes command only derisory support in the Australian labour movement. The left is fragmented; the Old left in a bewildering conflict of ideologies and allegiances and reduced to a shadowy existence; the short-winded New Left has mostly left the stage. If Left concentration is not on pleasing overseas patrons then it is too often on peripheral issues to the neglect of pressing problems facing the Australian people. For reforms of any significance the vast majority of Australian workers and their urban and rural allies will look to the election of Labor governments committed to social improvement.”

Lockwood was inclined to see the ALP’s role in the trade union movement as a likely subject for early attention. “The ALP, which commands the votes of the overwhelming majority of unionists in political elections, is under-represented in leadership of key unions. Where the overwhelming majority force of unionists is under-represented, danger and defeat often threaten. This is a problem I’ve no doubt the ALP will be considering soon keeping in mind the need to avoid the serious errors of the disbanded Industrial Groups.”

After 50 years in the thick of Australian Left politics, Rupert Lockwood is looking forward to finishing his memoirs. He has travelled a full circle from attraction to the ALP to membership of the CPA, rejection of Stalinism and support for the ALP. His memoirs will be the record of an adventurous life, a story worth the telling.

Postscript (2015)

Lockwood (1908-1997) never did write the series of memoirs and books contemplated and alluded to in this article.

I remember asking Laurie Short’s opinion about interviewing him. We both were keen to get the real story on Document J, a scurrilous document, full of opinions and gossip about the Australian political scene, circa the early 1950s. This had featured prominently in the Australian Royal Commission on Espionage, set up in 1955 following the Petrovs’ defection. I had hoped that a relatively tame and sympathetic profile article might get him to open up more. Lockwood was good company, witty, sincere, castigating of his old colleagues. But cagey and fearful of being typecast as another “the God that failed” ex-Comm tragic. Richard Crossman (1907-1974), the leftwing British intellectual and future UK Labour Cabinet Minister conceived the idea of editing a book by authors once actively involved in or fellow travelling with communism. The resulting book, six essays by Louis Fischer, André Gide, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, and Richard Wright, The God that Failed (1949) encapsulated stories of disillusion with and abandonment of communism. The phrase the book’s title coined Lockwood insisted was misleading in his case. He had good reasons to join (western capitalism was rotten) and did not want to be perceived as accommodated to the system. Stalin, the slavish following of the Party line, was unforgiveable, and yet… His mind was a complicated amalgam of principle, intellectual wrestling, vanity, and confusion. A lot of Lockwood’s secrets died with him.