Peter Sekuless’ biography of one of Australia’s most famous fellow travellers reveals a gullible personality whose involvement in politics was often pure caricature.

Jessie Street is mentioned in David Caute’s work The Fellow Travellers as an example of the Australian establishment gone to seed.1

Of the establishment she certainly was, lived and had her being. Jessie Street, née Jessie Mary Grey Lillingston, was the scion of a rich family of squatters who had settled in northern New South Wales. Her husband, Kenneth Street, whom she married in 1916, followed in the footsteps of his famous father, Sir Phillip Street, by becoming Chief Justice of New South Wales.

After graduation in 1911, Jessie Lillingston toured the world and made contact with various feminist organisations. She became immersed in campaigning for comprehensive sex education and for equal rights for women. On her return to Australia in 1916, she helped to form the NSW Social Hygiene Association. Sekuless thoroughly chronicles these events and discusses “the attributes that made her the leading feminist of her day.”2 Her participation in such causes was interrupted in 1921, after the birth of her third child. Sekuless writes:

…apparently disillusioned with women’s organisations, Jessie Street devoted her energies to a much-needed commercial enterprise. After the war, properly trained domestic servants were in short supply. This problem was a frequent topic of conversation among Jessie Street’s social peers, and in 1923 she established the House Service Company, which trained and supplied domestics.”3

Mrs Street’s devotion to serving the community’s needs knew no bounds, nor irony.

Her visit to the Soviet Union in 1938 filled her with the fantasy that at last she had found a society where all lived freely, men and women equal. She describes in her biography, Truth or Repose, the startling scenes she witnessed as she travelled by train through Russia:

In the morning I woke early and pulled up my blind to look out. The country reminded me of Australia. We ran through timbered grasslands with a few cattle and saw an occasional house or a man riding a horse. The railway line between Moscow and Negeroloya was a single track and evidently it was now being duplicated. Gangs of men and women were working together on the new track. Another novel sight, I had never seen women working on railway tracks before. As the train went past the passengers waved and they and the men waved back. In a little while we stopped at a station. I was still lying in my bunk looking out of the window. There were quite a number of men and women peasants on the platform walking round with large baskets. On the Continent the station master gives the signal for the train to proceed by waving a red-and-white disk attached to a longish handle. When our train began to move we passed a young woman in uniform waving this red-and-white disk. My interest was aroused. Suddenly I remembered I had been told before I left Australia that men and women had equal rights in the USSR. I said to [my daughter] Philippa I have never before seen women train conductors, track workers, or a woman station master. I am going to see at the next station if the engine driver is a woman. We both hurried up and dressed and at the next station dashed along the platform to the engine – and – the engine driver was a woman.4

Mrs Street was cross with only a few aspects of the new nation she had discovered. After attending a church service she said: “I thought it might have been a good thing if the communists had taken some steps to prevent the insanitary kissings of icons, etc., and forbad the presence of the frightful looking beggars outside the church.”5 The fact that there were beggars outside of the church did not strike Mrs Street as indicating something rotten in her Utopia. How the beggars would be removed is also not discussed, merely that they should be removed. Only then could Paradise look neat and tidy.

After her visit to the Soviet Union, Mrs Street’s life entered a new and controversial phase. In Australia she joined Soviet friendship societies and toured the country lecturing about her Pauline conversion. During World War II she organised the ‘sheepskins for Russia’ appeal which gained her worldwide fame. But her work also made her notorious to many people. Sekuless documents the occasions when Mrs Street was attacked as a communist and ‘smeared’ as a member of ‘communist fronts’.6 All of those accusations are presented by Sekuless as the slings and arrows of outraged McCarthyites. But the question to what extent some of the groups Mrs Street belonged to were CPA fronts is not analysed at all. Certainly she was not a member of the CPA. She was a member of the ALP from 1939 to 1949, and she once quipped that she could never join an organisation like the CPA which had no women on its executive committee.7

But many of the organisations she became involved in, for example, the Society for Cultural Relations and the Australian Peace Council, were formed at the behest of the CPA and at least initially dominated by communist cadres. Davidson’s history of the CPA and Sharkey’s work contain descriptions of the CPA’s tactic of establishing ‘united fronts’ through the bodies Mrs Street was a member.8 Unfortunately Sekuless fails to critically discuss this issue.

Sekuless’ description of Street’s association with the Federated Ironworkers’ Association is also poorly presented.9 Mrs Street became eligible to be a member of the FIA after working during the war in a munitions factory for some weeks. Nothing is mentioned in Sekuless’ biography of the occasions when Mrs Street strolled out of her chauffeur driven car, walked into FIA meetings and supported the Thornton leadership. She was nothing if not loyal.

The epic ironworkers’ union battle in the 1940s and 1950s uncovered ballot-rigging on an unprecedented scale. Clarrie Martin, Attorney General of New South Wales, James (later Senator) McClelland, who was himself expelled in the middle 1940s from the FIA on dubious grounds, and John Kerr, future Governor General of Australia, were the legal masterminds behind Laurie Short’s successful legal battles with the FIA leadership in the 1940s and early 1950s. Sekuless lamely comments: “Neither side held the monopoly over virtue and skulduggery” and then states:

One previously unpublished story concerns an issue of the still-Communist-controlled Labour (sic.) News [official journal of the FIA] immediately before an important union election. The “Groupers” knew that the Communists would use the journal to promote their candidates. To counter the dissemination of Communist propaganda, the Groupers hijacked fourteen mailbags containing the entire pre-election issue from a post office and pulped the copies. Disposal of the mail bags was a more difficult problem. Defamation laws prevent further elucidation, but apparently John Kerr was not involved. Labour (sic.) News was firmly in Short’s hands by the time of the union’s national conference in January 1952.10

There are a number of factual errors in this passage. First, Short did not have control of Labor News in January 1952. The confiscated issue Sekuless refers to was the February 27, 1952 issue of Labor News. Second, Sekuless is not revealing anything new about this matter. The seizure of the February 27th issue was reported in the next issue of the paper and was well-publicised in the daily press.11 Third, Sekuless’ reference to mail bags being stolen is pure invention. In fact, Sekuless should have consulted the March 12 issue of Labor News, still under Communist control, which describes the incident in some detail.

Here is the story of events in the order that they happened: Labor News was compiled and published as usual, and left the printery for the wrapping people on Wednesday, February 27.

On the morning of the same day Short told McClelland he wanted to stop Labor News reaching the readers.

[This is McClelland’s own story as told to a deputation of National Council delegates later].

Short said 80 per cent of the paper was an attack on him.

McClelland told Short he had the power to confiscate the paper and to write a letter authorising himself to seize it from the wrapping contractor.12

The article goes on to name Short and McClelland as the two culprits who confiscated the paper. Actually Short was not directly involved – McClelland was accompanied by a friend who assisted him in removing the paper from where they were being wrapped. There was no hijacking of mail bags.

McClelland believed there were several grounds for Short confiscating the paper. First, the February 27th issue was illegally authorised by “Leslie John McPhillips, Assistant National Secretary, Federated Ironworkers’ Association” yet he was no longer an official of the union by virtue of Mr Justice Dunphy’s ruling on the 29th November, 1951 in the case of Short v. FIA that “there was fraud, forgery and irregularity on a grand scale” in the 1949 FIA elections.13 Second, Labor News was being printed behind the back of the official National Secretary of the Union, Laurie Short, and contained libellous propaganda directed against him.14

Obviously, in his discussion of this incident, Sekuless has confused his facts and failed to properly support his allegations.

Sekuless is also inadequate in discussing Roman Catholic influences on Mrs Street’s career. The Catholic Church is blamed for almost every setback in her political career.15 But in the absence of documented supporting evidence, these allegations can only be regarded as vulgar prejudice. In this respect Mrs. Street’s autobiography is revealing enough:

When I joined the Labour (sic) Party I had assumed that the party consisted of people who believed in Socialism as opposed to Capitalism and that they were controlled by their freely elected committee and leaders. I did not understand the ramifications of the influence of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in the Labour (sic) Party, and the extent to which its members are indoctrinated and have to obey the orders of its priests. Had I done so I might have hesitated about joining. The Labour Party had a socialist objective and I was a socialist, so I joined.

Certain Roman Catholics are always talking about communist “infiltration” in other organisations, but from my experience some Roman Catholics are past masters in the art of infiltration and the infiltrators obey secret orders. There can be few organisations in any field other than the Protestant Churches into which they have not infiltrated.16

This conception of Catholics infiltrating organisations, including the ALP, and obeying the secret orders of priests is plain paranoia. It was true that certain Catholic ALP politicians frustrated Mrs Street’s political ambitions, but in no sense could this be described as a conspiracy by the Catholic Church per se. Such myopia was not limited to the Catholic Church.

Sekuless’ biography does not conceal the worse excesses of Jessie Street’s infatuation with the Soviet Union. In 1953 she flew to Moscow to attend Stalin’s funeral and she wrote back to the Friends of the Soviet Union about her love for Number One:

Stalin was loved and honoured by his people [as] few men in his time have been. To speak metaphorically, we may regard Stalin as the Moses of the oppressed people of the Soviet Union. But he was a Moses who not only lived to lead his people into the promised land, but for 35 years, was able to guide and help them.17

Her faith in the Soviet system withstood the traumas of the invasion of Hungary and the revelations of Khrushchev’s 1956 speech. Stubbornly, she refused to sully her imagination with any facts which would contradict the ‘country of the mind’ she found on her first visit to the USSR.

Doubtless she was ignorant of the worst aspects of exploitation of Soviet women, but her attitude would probably have changed little had she known that equal status and opportunity were not a reality in socialist countries. Jessie Street believed that women’s equality in fact would flow from women’s equality in law; therefore she could pin her faith to a piece of paper, the Stalinist Constitution, even though the real situation did not match the written word.18

She was completely blinded by the ‘burning bush’ she found in 1938. Nothing could disturb the passionate intensity of her faith.

Jessie Street’s involvement in the public discussion and promotion of sex education, the movement to gain equal pay for women, and in the social and political advancement of the Aboriginal people are well documented in Sekuless’ study. He probably exaggerates Mrs Street’s contribution in the 1950s and 1960s to the establishment of the first national Aborigines’ organisation, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement, formed in 1962, and the passing of the 1967 referendum. Sekuless claims: “Neither the establishment of a national body nor the passing of the referendum would have taken place without Jessie Street.”19 But her influence and finance, although helpful, was not essential to those endeavours. After all, Mrs Street was away from Australia for six years between 1950 to 1956, visiting World Peace Conferences, travelling through Eastern Europe and the USSR. On her return to Australia in 1956 she launched a petition to amend the Constitution; but she was only in Australia nine months before she was overseas again. She was also frequently overseas in the early 1960s. By 1963 the petition campaign had petered out. 20 As Mrs Street freely acknowledged, the 1967 referendum campaign was successful because of the work of those of the aboriginal community – “God helps those that help themselves – and God help those that don’t”21 was one of the expressions Mrs Street used to encourage the referendum campaigners.

Sekuless’ failure to document many of his assertions and interpretations is the major fault of this biography. The rewarding aspect of his work is that it provides enough facts and quotes to support the assessment which introduces this review.

Notes

1. Caute, David, The Fellow Travellers, Quartet Books, London, 1977, p. 248.

2. Sekuless, Peter, Jessie Street. A Rewarding But Unrewarded Life, University of Queensland Press, 1978, p. 25

3. Ibid., p. 35. My emphasis.

4. Street, Jessie, Truth or Repose, Australasian Book Society, Sydney, 1966, p. 145. Cf., p. 160.

5. Ibid, p. 160.

6. Sekuless, Loc. cit., pp. 96-97; 106-107; 109; 148.

7. Ibid., p. 161.

8. Davidson, Alastair, The Communist Party of Australia, A Short History, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1969, pp. 72-93; 104-106. Sharkey, L.L., An Outline History of the Australian Communist Party, Sydney, 1944, pp. 30-33.

9. Sekuless, op. cit., pp. 156-158.

10. Ibid., p. 157.

11. ‘This is the Paper They Tried to Stop’, Labor News, March 12, 1952, p. 1; Sydney Morning Herald, February 29, 1952, p. 3.

12. Labor News, op. cit., p. 1.

13. For a discussion of the case, see Wells, Fred, ‘Defeat of the Communists in the Federated Ironworkers’ Association’, unpublished paper, 1972, mimeo, pp. 10-12. For confirmation of ballot-rigging in the FIA in the 1940s see Gollan, Daphne, ‘The Memoirs of Cleopatra Sweatfigure, Part 2’, unpublished paper, mimeo, 1978, pp. 11-14.

14. ‘Why the February Issue Was Seized’, Labor News, April 2, 1952, p. 3. This was the first issue of the journal which Short edited and ‘controlled’. It was published after the election in March 1952 of a new National President, National Vice President and Assistant National Secretary — all Short supporters. The merits of McClelland’s legal advice is beyond the scope of this essay.

15. Sekuless, op. cit., pp. 59; 102; 125; 181.

16. Street, Jessie, op. cit. p. 317.

17. Sekuless, op. cit., p. 159

18. Ibid., p. 160.

19. Ibid., p. 170.

20. Ibid., p. 175.

21. Ibid., p. 180.

Postscript (2015)

I submitted this to Meanjin magazine. But they never published. One anonymous reader of the manuscript commented: “It seems a competent review; but I don’t feel that J.S. is significant enough to justify us in giving our limited review space to a fairly long critique of Sekuless’s book.” The other reader proffered: “A good story, but surely would be better set out as an article, at more length than this review.” So it was either too long or too short, or not otherwise appropriately formatted – which was frustrating to hear.

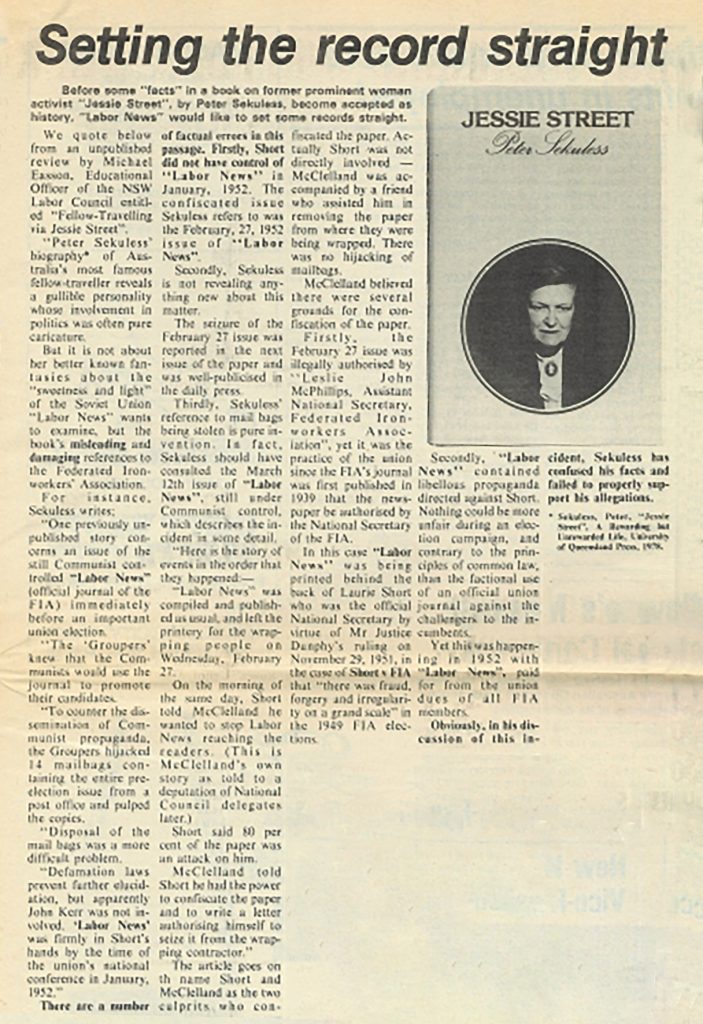

An edited version appeared under the heading “Setting the Record straight”, Labor News [journal of the Federated Ironworkers Association], Vol. 33, No. 247, new series, May/June/July 1982, p. 11.