Speech delivered in October 1990 to the Sydney Institute and reprinted in The Sydney Papers, Vol. 2, No. 2, Spring/Summer 1990, pp. 94-100.

Recently I had occasion to think hard about The Sydney Institute due to a contribution made by Sydney personality and political stirrer, Bob Gould, at a conference on privatisation which I was attending. There was a raging debate by various members of the Labor party over the privatisation issue. Bob Gould decided to try to discredit me, among others attending the conference, who were arguing the case for some change in policy. He did so by holding aloft the July edition of The Sydney Papers and referring to photographs from the Inaugural Larry Adler Memorial Dinner. Bob Carr, Helena Carr, Stephen Loosley and Michael Easson were all there. He thought this would demolish our case. We were linked to The Sydney Institute. I wonder what Bobby Gould would make of this evening!

I would like to talk about an issue which is very much at the heart of my recent thinking – the question of Australia and immigration. A book I have edited titled Australia and Immigration: Able to Grow? will be launched by Neville Wran on 13 November 1990. It canvasses viewpoints, including whether we are demographically able to sustain a larger population and what would be some of the ecological or environmental issues related to a larger population growth for Australia. I recommend this book and what it attempts to do – to grapple with the question of whether Australia, for a range of economic reasons, should be encouraging greater immigration intakes or whether intakes should be reduced. It further canvasses whether Australia would become a more insular and isolated society by being afraid to grow or to entice people to come here.

It is interesting to reflect on the debate that has occurred in Australia since the release of the FitzGerald report, Immigration: A Commitment to Australia. This report was named after the Chairman of the Committee to Advise on Australia’s Immigration Policy, Professor Stephen FitzGerald.

When that Report came out at in early 1988 Fitzgerald said:

Over time the need for a strategic rationale for immigration was lost. The Immigration programme came to be driven by its own momentum and external stimuli, rather than planned initiative within disconnected both internally and from the mainstream of government policy. The economic rationale for immigration become diffuse, unsupported, and under some administrations, almost unnoticed.

FitzGerald recommended that due to the confusion that existed in the community as to the reasons for the immigration intake, the government ought to foster a more balanced debate on immigration, including consideration of the economic and social implications. The FitzGerald Report recommend the establishment of the Bureau of Immigration Research (BIR), which is about to hold its first conference next month. Also, after the report’s release, the government accepted the recommendation to target, over a three-year period, an intake of about 140,000 immigrants to Australia per year. This is a slight increase over previous years.

Subsequently and around the time the report was released, there was a debate about whether Australia should be comfortable with the number of immigrants from Asia and non-English speaking backgrounds. I think that controversy had a chilling effect on the immigration debate generally. The Australian government appeared a fearful about publicly arguing for higher immigration because of this and it was also a major factor in the decisions to reduce the immigration intake this financial year to about 126,000.

The most disappointing thing that occurred with the FitzGerald Committee Review was that we missed an opportunity to substantially increase the Australian immigration intake. Shortly before the release of the Report, I met with an adviser to the Prime Minister of Canada, Peter White. He commented that at the time Canada was attempting to attract about 220,000-250,000 immigrants annually and that Canada supported a very large immigration program. They were very aggressively targeting Hong Kong. I thought that at the time there was also in Australia a consensus among the elite, straddling the political spectrum, that was sympathetic to greater immigration intakes. This, however, was not the case, and it was not the case because of the highly-charged, politicised debate concerning our immigration intake. I regard this as disappointing. In thinking about the immigration issue, it was interesting to collect a range of views that are represented in the book under discussion: Australia and immigration: Able to Grow? (Lloyd Ross Forum/Pluto Press, 1990.)

In my research, I came across an article by the economist Allan G.B. Fisher. He wrote at the end of the 193os speculating on why Australia was experiencing a negative increase in population and why many of the migrants who came from Great Britain in the 1920s and 1930s were then returning. He considered whether Australia’s population would continue to decline and whether Australia would ever be able to attract migrants from the British Isles and elsewhere in the future. It was staggering to come across that article. It seemed to be quite an interesting point to argue when a short time later, in the immediate post war period, hundreds of thousands of people in Europe and in Great Britain were determined to come to Australia.

What was once normal and enticing, however, is not a significant option for most people in Europe today. It is increasingly an eccentric choice for people in Holland, Germany, Italy or many other parts of Europe to decide to migrate to this country. Allan Fisher’s argument near the beginning of the Second World War about our being unable to entice migrants from Europe is worth reconsidering today. With the exception of Great Britain and Ireland, there does not seem to be much interest in migration to Australia from Western Europe. (Though it is noticeable that in the last twelve months there obviously has been an increase in interest from people in Eastern Europe.)

I have begun to wonder about these sorts of arguments in relation to the changing economic situation in many of the countries to our immediate north. As we debate in Australia whether or not we should be Asianising the Australian population, I wonder what the situation in those countries will be in ten or twenty years from now as their economies accelerate. It might ultimately become an eccentric thing for people from those countries to contemplate migrating to Australia.

Professor Ross Garnaut in his Report on the North-East Asian Ascendancy made some observations which, to my knowledge, have gone unremarked. He noted that there is now an opportunity for Australia “to recruit to its citizenship young, well-educated and professionally accomplished people from Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Republic of Korea. This opportunity may be available for a decade or less. It will diminish as political uncertainties are resolved and, as in Europe, there is a rise in living standards which will reduce the attractiveness of immigration to Australia. There is a strong case for making good use of this opportunity while it lasts.” Unfortunately, there is little evidence that this opportunity is widely recognised as such. Indeed, the observation made in the Garnaut Report seems to have gone unnoticed in the debate about Australian economic opportunities in North-East Asia.

There is one important argument for such immigration. While Australians have not succeeded in developing trade opportunities in the Asia-Pacific region, an injection into Australia of able migrants from some of the dynamic economies of Asia may help to change that situation. Such migrants may be more interested, willing and able to develop trade opportunities between Australia and their countries of origin.

Further, if Australia could increase the number of professional and highly skilled workers in, for example, the computing, engineering, applied science and business areas this could assist Australia’s potential to expand its industry and trade in many areas. In any event there are now many opportunities to attract extremely high- skilled migrants in the case of Hong Kong prior to the Chinese government takeover in 1997 and in Taiwan and Korea. That opportunity is likely to recede within a decade or so.

All of these arguments seem to me to point to the need for an enterprising approach in the recruitment of migrants.

Having posed the question of whether there will be any migrants in the near future and whether the current attractiveness of Australia for potential migrants will diminish increasingly in the years ahead, we ought now to be considering the range of very talented people that we already have in this country from Europe and to consider that we have a similar opportunity over the next twenty, thirty and forty years in the case of our immediate region.

What does all this mean in terms of how I would run the Australian immigration program? Let me say that I favour a policy that would significantly increase Australia’s immigration intake. I would extend the immigration intake in the skilled areas and aim to increase the immigration intake to around 200,000 per year. I would increase the focus on economic factors, including English language ability, in the selection of migrants, and I would also argue for a more enterprising approach by the Department of Immigration in selecting migrants that are to come here. At present, it seems to me we have a very bureaucratic approach to the way that we deal with migrants. We know that each year about a million people seek to apply to migrate to Australia. The approach at the Department of Immigration is merely to sift through those people to decide who are the best, based on laid down points of criteria.

In my view, however, we should be more aggressive. We should attract migrants and actively pursue the ones we want. We should advertise the opportunities that are available in countries to our north as was indicated in the Garnaut Report.

There are various dilemmas that are part and parcel of the immigration debate. I think one of the reasons the debate is interesting is because answers need to be given to a range of policy issues relevant to Australia’s future before one can come to a considered view on immigration policy. Amongst those issues are how we improve the health of the Australian economy and what methods should we support to enable and encourage the debate in Australia without it being marred by arguments that migrants will wreck employment opportunities and cause an increase in unemployment. Such dilemmas require a determined approach by the government of the day to tackle inflation and the major problems we face as a nation. Just as the industrial relations debate could be recast with a lower level of inflation, I believe the immigration debate would be transformed with similar economic recovery.

The second issue that I think is relevant in considering the direction of policy and which is a dilemma for anyone arguing for changes in the immigration policy is the major infrastructure issues that have been raised recently, for example by the leader of the Opposition in New South Wales, Bob Carr. My own view though, is whatever the problems of Sydney, and whatever the road, transport, and health needs might be of Sydney, it is wrong to say that migration is the cause of those problems.

Whatever reasons might be given for those situations, one should not blame migrants. I think the modest level of immigration that I would recommend of 200,000 annually, is less per head of population than the level of immigration we had for much of the 1950s. We ought to be tackling important infrastructure issues, but I do not regard those issues as decisive arguments against increased immigration intakes.

The third dilemma is the arguments that Senator Peter Walsh canvassed in his article in the Financial Review earlier this year, which is that even if we introduced more talented people, we would not necessarily have significant economic change as a result.

In other words, just because you have a lot of talented people with computer, science and business qualifications, it does not automatically translate into jobs and business opportunity. This is undoubtedly correct, but I also think that it would not harm Australia either. My argument would be that it could do some good. Some of the arguments relevant to this are dealt with by David Clark in his Chapter in Australia and Immigration: Able to Grow? It is fair in looking at this question to say that there are no clear-cut answers to some of the economic issues that are raised in the debate. Though it is interesting that the Bureau of Immigration Research (BIR) recently released a report strongly arguing for the positive economic gains that migration can provide. It will be interesting to follow the debate about this at the forthcoming BIR Conference.

What I have tried to do this evening has been to raise some issues that are relevant to my title and to briefly canvass economic, demographic and other factors relevant to the question of whether we are able to grow the population of this country. I have tried to make some suggestions as to how immigration policy might be modified, including the role of the Department of Immigration.

I will now just share an anecdote with you. I am increasingly persuaded by the argument that we should be a lot more rigorous in the selection of our migrants. Given that there is an argument challenging the idea that migrants are economically good for the country, maybe one way of handling that viewpoint is to be much more selective with the people we allow in and to require English-language competence as a rule to be applied to not only skilled migrants but also to a significant proportion of family migration. I am convinced of that and convinced also of the need to be a little more stringent in our requirements of the skills of migrants coming into Australia.

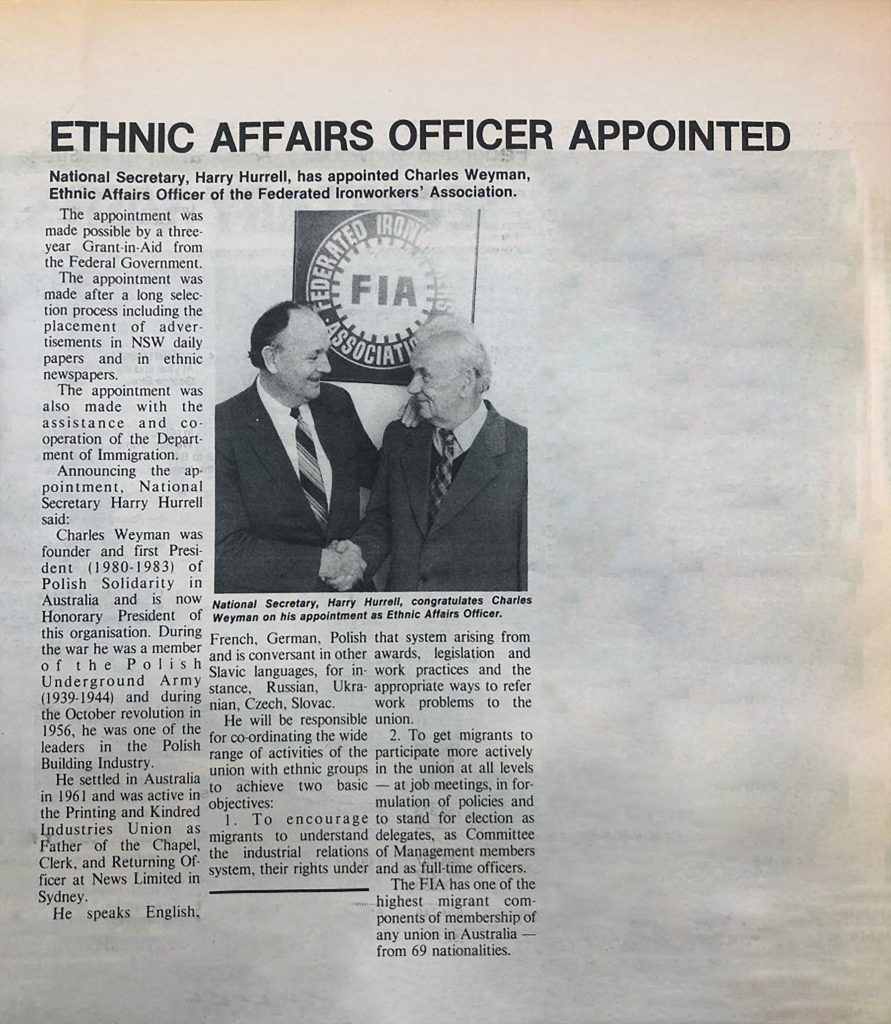

After I edited the book and sent it to the publishers, however, I got a call from a fellow called Charles Weyman who used to work at the Ethnic Affairs Office of the Federated Ironworkers’ Association (FIA). Weyman was originally a refugee from Poland and a person who campaigned in Sydney and Australia for the pro-Solidarity organisation. He mentioned to me that he knew of many families in Australia from Poland and many others seeking to migrate here. He argued against the arguments I just offered and the conclusion I conveyed. He pointed out that most of the refugees and many others who have made it in Australia might never have been selected according to the entry criteria that I outlined.

This raises the question whether we can be terribly confident about predicting how “successful” will be the migrants selected to come to Australia. Nonetheless, I am not wholly convinced of Weyman’s views, even if I am now not so sure of my original stance. An important consideration is that there probably will be a lot more public support for higher levels of immigration than currently if a much more rigorous, economic criteria were applied to the selection of migrants. I would hope that there will develop a bi-partisan approach on such issues; one that was denied, unfortunately in 1988, when the FitzGerald Report was released.

Postscript (2020)

Minor edits were made to the article, a transcript of what was said on the night of an address to the Sydney Institute. Bobby Gould (1937-2011), mentioned early in my paper, was a radical leftist bookseller, one of the more colourful anti-Stalinist “Trot” characters to find a presence in the Australian Labor Party.

Charles Weyman (1920-2003) was someone I regularly liaised with on immigration issues from the early 1980s onwards. He was close to and eventually worked full-time as a migrant welfare officer of the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA) union. In the early 1980s, he told me generally of his experiences under the Nazis and the communists in Poland. He hated totalitarianism of any type.

At the time, I did not imagine how extensive, personal, and overwhelming was his expertise. Born Karol Wejman in Tomaszow, Poland, on 24 September 1920,1 he died in Sydney on 17 July 2003.2

During the Second World War he forged documents to ‘forget’ the Jewish origins of some people, he smuggled some Jews to safety; he wrote for the underground press, was arrested by the Germans, and escaped several times. As a member of the Polish resistance, he witnessed the Warsaw uprising. After the war he observed that if the Allies had read, studied, and listened to what the Polish underground had smuggled out or reported, more lives could have been saved. The concentration camps and their crematoria should have been bombed before liberation, he said.

After the war, Weyman worked as a journalist in Wroclaw for 4 years before being dismissed by the Polish authorities for anti-communist activity.

Unemployment, unskilled and low-paid work in the building industry followed. As a momentary thaw in hardline rule melted away some of the worst features of Polish communist rule in 1956, he became President of a building section of the Polish Congress of Workers’ Councils, an attempt by various workers to create autonomous, independent trade unions in Poland.3 Zuzowski notes: “…1956 witnessed the establishment throughout Poland of a great number of independent workers’ institutions at the plant level, called workers’ councils” or works councils.4 At one point, Weyman, with others, was locked in negotiations with the government over reform and allowing greater political freedom.

Khrushchev’s denunciation in February 1956 of Stalin’s crimes and the cult of Stalinism5 had an enormous impact, globally, particularly in Poland. Poles could no longer stomach sea-water showcased as lemonade.6 The Poznań protests in late June 1956 by workers demanding better working conditions were met with violent repression. 1956 “was not only a political crisis but also an economic crisis, of which the unrest among the workers was an unambiguous indicator.”7 Between 57-100 people were killed. These were some of the key events which led to the promise of greater freedoms, as Władysław Gomułka (1905-1982), leader of the reformers’ faction, came to power in October 1956 and eased Stalinist controls and encouraged greater liberalisation in Polish society.

Under Gomułka, there was talk of a “Polish route to socialism.” But due to pressure from the Soviets, opponents within the ruling Polish United Workers’ Party, and the leader’s own instinct for survival, the regime became more rigid and authoritarian. Accordingly, the Congress of Workers’ Councils only flourished until suppression, some deaths, arbitrary and targeted arrests – including Weyman, briefly, and a complete communist crackdown.

Aged in his early 40s, seeing no future in Poland, with his wife and two daughters, he migrated as far away as he could – to Australia.

In his adopted homeland, ignorance of the Polish situation and double standards annoyed him. When the Australian Council of Churches called for the Rhodesian Information Centre in Sydney to be shut down by the Australian government, Weyman thought that a double standard operated. If the Rhodesian office deserved closing because it was the unrepresentative agency of a despotic regime, then did not the various Eastern European consulates and diplomats deserve similar disdain? Weyman wrote: “…we are entitled to expect that the Australian Council of Churches will now demand the closure of Polish (and other communist) embassies in Canberra. The Polish Embassy is representative of an illegal regime supported by no more than 1 per cent of the population”,8 thereby incurring the wrath of fellow-travelling leftists. For example, the Australian novelist Dymphna Cusack9 testily condemned Weyman’s bigoted ignorance about the Poland she had seen on several subsidised trips. She wrote:

The claim that only 1 per cent of the population supports the present government is sheer nonsense. No country, particularly one so terribly devastated as Poland during the Nazi occupation, could build back such a prosperous society with 99 per cent dissidence.10

Weyman soon replied:

The letter “Impressed by Poland today” (October 3) by Dymphna Cusack is a typical example of Leftist insolence.

Leftist, because no one else would see any prosperity in the miserable economic situation of communist Poland, where hardworking people are earning less than the unemployed in Australia, and where unemployed people are getting nothing at all.

Insolence, because Dymphna Cusack, after two holidays in Poland, pretends to know more than I do when I was born, educated and worked in Poland until June 1961, when I emigrated to Australia.

What sort of prosperity is it when you have to work a full day to earn one kilogram of beef and, if you get it, consider yourself lucky, because of the constant shortage of everything, or when you wait for a small apartment for 10-15 years?

Yes, it is true that Poland “was terribly devastated during the Nazi occupation.” I know. I was there every day of the five years and four months. I fought Nazis in the Polish underground army. But that was long ago.

Since the end of the war 32 years have passed, and immense profits usuallv taken by capitalist sharks and aristocratic parasites are now taken by the State for the good of the people — or are they?

Dymphna Cusack says that it is sheer nonsense to claim that the Polish government is not supported by the population. However, it is generally known that four revolutions have taken place already in Poland: in October 1956 (in which I took part as one of the leaders for the building industry); March 1968; December 1970; and June 1975.

The Catholic Church in Poland has been constantly persecuted, but to destroy it has been so far beyond the power of the communists, because the Church has the full support of the population. We shouldn’t, however, forget that Cardinal Wyszynski spent five years in jail and many bishops and hundreds of priests also served long jail terms.

I would like to assure Dymphna Cusack that my information as a press officer is always correct, and, what’s more I can prove it. Any reader who still has the slightest doubt about the situation in Poland would he advised to watch the ABC Channel 2 special: “Three days in Szczecin” (Wednesday, October 12, 8.30 pm). It tells the story of the December revolution in 1970, when hundreds of workers were killed by police. Strangely enough, this was the same year in which Dymphna Cusack spent a three-month holiday in Poland and learned so much about “freedom and prosperity” of the country.11

Weyman rose to contest lazy, communist party-line drivel. His patience was tried by naïve fan notes about a country he knew all too well.

Weyman came to the attention of the anti-communist union leader Laurie Short (1915-2009), the National Secretary of the Federated Ironworkers Association (FIA) from 1951-1982, perhaps through Richard Krygier (1917-1986), the Polish-Jewish émigré and moving spirit behind the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom, the publishers of Quadrant magazine.12

Short became patron of the Association of Free Poles in Australia. In the early 1980s, Short wrote about the communist crackdown of free trade unions in Poland.13 Through a telegram to Herman Rebhan, the general secretary of the International Metal Workers’ Federation, Short invited Lech Walesa to visit Australia.14

In 1981 from Israel, it was announced Weyman would receive the Yad Vashem Medal of the Righteous for his work in saving Jews from extermination. (On 6 September 1995 he also recorded evidence to the Shoah Foundation on certain of his activities and witness during the War15.) He lived in Tomaszow Mazowiecki, Brzeziny, and Lodz, Poland. He assisted Jewish friends and strangers by supplying basic goods, providing forged documents, illegal transfers and arranging shelter to families in the Tomaszow Mazowiecki and the Stanislawow ghettos in Poland

On the Yad Vashem website is this account:

Karol Weyman lived in Tomaszow Mazowiecki. He had Jewish friends before the war, during his high school years. “I was brought up in a worker’s family and for my family all people were equal, with no regard to faith or nationality,” wrote Karol in his testimony to Yad Vashem. During the war, with the help of a friend who worked for the municipal council until 1943, he received 30 extra food cards every month. The food he got using the cards was given to Jewish friends, including his schoolmate Brzezinski. In the winter of 1941-42, Karol managed to get a ton of coal into the ghetto, half of which he left in the apartment of a man who lived close to the ghetto gates (“it was the best place to unload”). The rest he took to his acquaintances, the Aronson family. Before the liquidation of the local ghetto, Karol smuggled his high school friend, Maria Aronson, out of the ghetto. He took her, initially, to his sister and then to Warsaw, where he found her a job working for a Polish family after equipping her with false documents. Maria stayed there until the liberation and, in April 1945, she married Karol. During the war, Karol came to know Maria Halska and her son in the Tomaszow Mazowiecki ghetto. He met them through Maria Aronson. “My only family, my brother-in-law, my sister-in-law and their son, lived in Stanisławow. When the Gestapo took my brother-in-law, my sister-in-law turned to me to help her get out of Sanislawow,” wrote Halska.

She continues: “I then turned to Karol Weyman. Weyman went to Stanisławow and brought me all of my sister-in-law’s valuables. Next, he took my sister-in-law and her son to Krakow. And moving with a Jewish boy was life threatening!” Edward Kreutzberg-Orlicz also enjoyed Weyman’s help. Weyman helped him flee the Tomaszow ghetto and get to Warsaw where he also arranged a place for him to stay for his first few nights there. “He did all these acts… without any self-interest, and our family and the Weyman family were merely acquaintances,” wrote Edward. On March 31, 1981, Yad Vashem recognized Karol Weyman as Righteous Among the Nations.16

In 1981 Weyman was a compositor on the Sydney Daily Mirror newspaper having worked for News Limited for 8 years, a member of and active in the Printing and Kindred Industries Union.

In 1984 the FIA, after many years of close, informal work together, employed Weyman as one of its specialist officers.17

When I knew him, Weyman was also President of one of the Polish Ex-servicemen’s Associations; chairman of the local Polish radio and television board; President of the Association of Free Poles in Australia and Chairman of their newspaper, Solidarity.

In the early 1980s, I worked closely with Barrie Unsworth, Secretary of the Labor Council of NSW, the peak, co-ordinating body of the unions in NSW which was led by right wing Australian Labor Party (ALP) types – social democrats with a long history of opposition to communism. Unsworth, arguably, was the toughest of them all – and vigorously supported campaigns for trade union and human rights in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Indeed, after becoming Secretary (head) of the Labor Council in 1979, the Committee for Workers’ Rights in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe was formed, closely associated with officers of the Labor Council.18

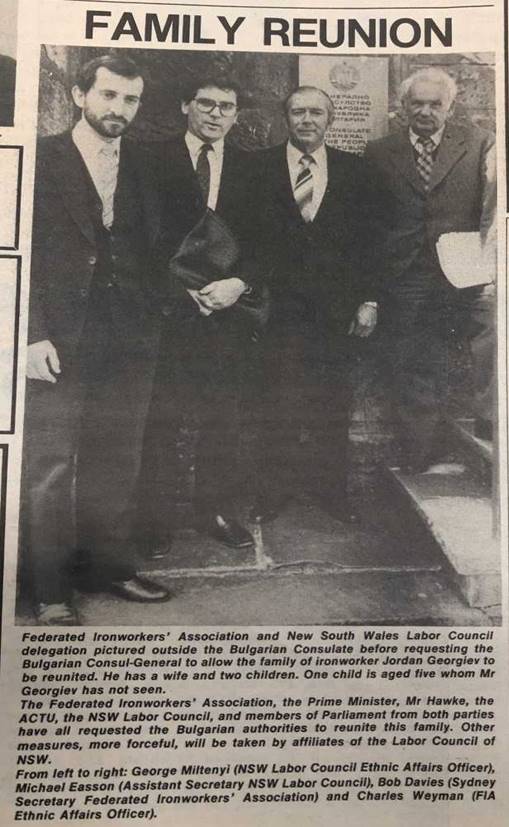

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, relatives of FIA members sought reunion with family from Bulgaria,19 Romania,20 Poland, and other Eastern bloc countries.21 With the assistance of the Municipal Employees’ Union in NSW (MEU), particularly Joe Cahill (1924-1995; NSW MEU Secretary, 1982-1989), and Jack Merchant (1929-2006; NSW MEU Secretary, 1989-1998) as well as other unions, the Labor Council imposed targeted garbage collection and other bans on the relevant consulates in Sydney to pressure the authorities to do the right thing. Our actions usually resulted in something positive – family reunion or at least an official response to our representations.

I remember Charles insisting that this sort of action was the only thing “these people understood.” He hoped some of the eastern European consular staff might feel demoralised that real workers in Australia were hostile to the pretensions of the so-called communist worker states that their consulates supposedly represented.

On a couple of occasions in the early 1980s, Pat Clancy (1919-1987; Federal Secretary of the BWIU, 1973-1985), the veteran pro-Soviet official of the Building Workers’ Industrial Union (BWIU), rang Labor Council of NSW Secretary Barrie Unsworth to vigorously protest our “reckless” actions. This only encouraged us to persist.

Not everyone supported the Labor Council’s actions, working with the FIA and other unions. For example, iconoclast, journalist, and intellectual Paddy McGuinness complained:

Right-wing unions and union councils can be just as bad as Left-wing. Conservatives are fond of denouncing union activities like the blocking of access to ports of foreign naval vessels suspected of carrying nuclear weapons, but have not yet denounced the impertinent interference in our foreign policy of the Right-wing NSW Labor Council, which delights in putting blackbans on Communist consulates.22

McGuinness preferred that the Australian government deal with any human rights and immigration complaints, that unions steer clear of global politics and just concentrate on union services and industrial relations.

The assistant national secretary of the FIA, Bill Hopkins, proudly observed in 1986 that the union had been instrumental in reuniting 30 families, mainly from communist countries –including 13 Romanian, 3 Bulgarians, 10 Polish – a total of 84 people. He said: “In some cases, this union with the co-operation of the NSW Labor Council, and other unions, have had to use the threat of industrial action before some embassies [and consulates would] move.”23 In other words, industrial action was used sparingly, after representations and seeking meetings, sometimes after many months of delay, waiting for responses.

Weyman also linked up with and gave support to Poles who defected to Australia in the early 1980s onwards. One newspaper report in early 1982 pictures Weyman in his capacity as President of Solidarity, the Association of Free Poles in Australia, meeting 7 of 15 asylum seekers who had jumped ship the previous month from the Polish ship Artur Grottger. They had gathered in his house in Croydon Park in Sydney to learn English.24

Weyman introduced me to visiting Polish dissidents, and was active in drumming up support for Solidarność, the independent Polish trade union and dissident political movement, and got me to speak at pro-Solidarity functions in Sydney. Along with Martin Krygier, in 1982 Weyman introduced me to the visiting Polish Solidarity thinker Adam Michnik (1946- ),25 who by then was in Australia to celebrate the end of communist rule in Poland.

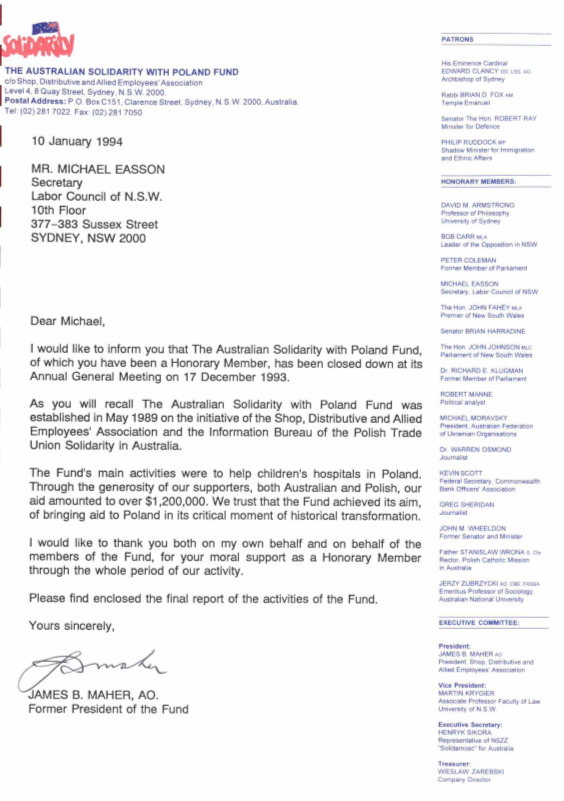

In the effort to arouse Australian interest and support for Solidarność, the Labor Council leadership co-operated with the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association, the SDA, and the Federated Clerks’ Union of Australia, the FCU, who through Jim Maher (1927-2009) and Joe de Bruyn, both of the SDA, and John Maynes (1923-2009; Federal President, 1954-1992) and Michael O’Sullivan (1941-2012; National President and the successor union, 1992-2004), from the FCU, were particularly active in the 1980s campaigning against martial law in Poland and promoting and supporting the cause of democracy, including the heroic actions by Lech Wałęsa, the leader of Solidarność in Poland.

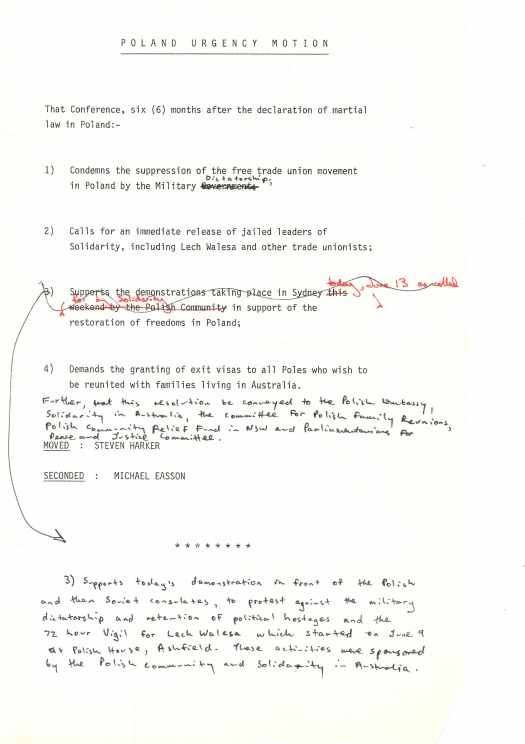

The FIA too were fierce and practical in their support, with Weyman looking up articles and providing research material for us to utilise in debate. At the NSW ALP Conference in June 1982 Steve Harker (FIA) moved and I seconded and spoke on a resolution opposing the imposition of martial law by the then Polish communist government and expressing solidarity with Solidarność. The resolution read:

That Conference, six (6) months after the declaration of martial law in Poland:

(1) Condemns the suppression of the free trade union movement in Poland by the military dictatorship;

(2) Calls for an immediate release of jailed leaders of Solidarity, including Lech Walesa and other trade unionists;

(3) Supports today’s (June 13) demonstration in front of the Polish and Soviet consulates, to protest against the military dictatorship and retention of political hostages, and the 72 hour Vigil for Walesa which started on June 9 at Polish House, Ashfield. These activities were sponsored by the Polish community and Solidarity in Australia;

(4) Demands the granting of exit visas to all Poles who wish to be reunited with families living in Australia.

Further, that this resolution be conveyed to the Polish Embassy, Solidarity in Australia, Committee for Polish Family Reunions, Polish Community Relief Fund in NSW and Parliamentarians for Peace and Justice Committee.26

Klatt quotes from an April 1981 memo sent home by the Polish Ambassador to Australia, ‘The Attitude Towards the Solidarity by Australian Political Circles’, which names Weyman as a key trouble-maker:

…in Sydney where pseudo-Solidarity assembled by provocateur Weyman is developing vigorous activity specifically for penetrating national ‘Solidarity’ by financial donations and support from outside of KOR’s power. Coteries of Weyman, Boniecki27 and others

have been profoundly implanted among the ‘anti-regime’ anti-Polish Polonia organizations. They see the ‘Solidarity’ as [an] anti-communist subversive force and aim at fueling this feeling through establishing regular personal contacts and financial and information contacts.28

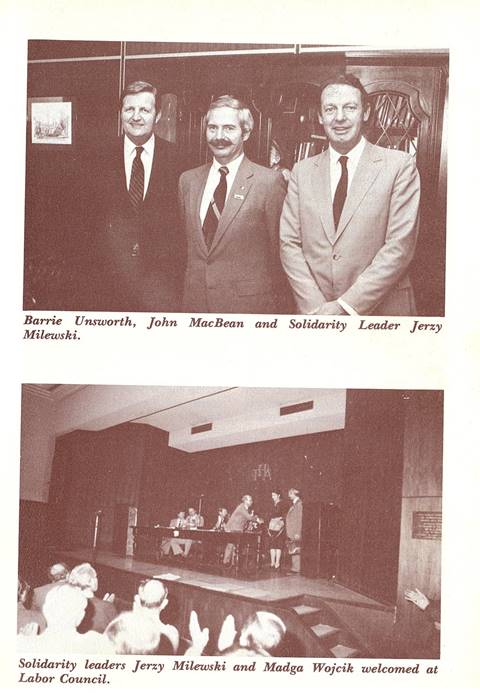

In August 1982, sponsored by two of the leading anti-communist led unions, the SDA and the FCU, Jerzy Milewski (1935-1997), President,29 and Magda Wójcik, the assistant head of Solidarność’s international department, visited Australia to promote the Solidarity cause and they spoke at meetings across the country including a Thursday night meeting of delegates to the Labor Council and separately at a function hosted by the Labor Council’s secretary Barrie Unsworth. Milewski was particularly impressive, dapperly dressed though with halting English language skills. He had a doctorate in mechanical engineering from the Gdańsk University of Technology and in August 1980 participated in a strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk which radicalised him against the regime.30 He was one of Wałęsa’s close supporters and confidants. After the main Solidarność leaders were arrested in Poland, with martial law declared on 13 December 1981, he and Wójcik happened to be abroad and remained in exile for almost a decade, with Milewski becoming co-organiser and head of the Solidarność office based in Brussels.31 In 1991 he returned to Poland and became a minister in the Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Wałęsa.

In 1988, with Wałęsa prevented from attending the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions conference in Melbourne (a body the ACTU was affiliated to), we decided to protest.32 As part of a wide call for industrial action, we caught up with Jack Merchant of the MEU, and Martin (Harry) Pitt (1931-2008), the then NSW Secretary of the Electrical Trades Union (ETU), to impose a union-ban on collecting the garbage and to temporarily cut off electricity supply from the Polish consulate in Trelawney Street, Woollahra (Sydney).33 From 11 March to midnight 19 March 1988 (the end of the ICFTU conference), the Labor Council imposed the following bans on the Polish consulate:

Postal services: ban on deliveries.

Garbage collection: ban on pick-ups.

Electricity maintenance and repairs: total ban.

Water repairs: ban on repairs.

Water and sewerage breakdown: total ban.

Building maintenance: total ban.

Transport distribution: total ban. 34

Under the heading “CIA Lovers Ban Polish Consulate”, the Australasian Spartacist newspaper, the most luridly crazy of the far-left newspapers, complained at the time that:

The recent bans imposed on the Polish consulate in Sydney by the CIA loyalists who run the NSW Labor Council were the latest blow in their anti-communist campaign against Soviet-bloc diplomats, in cahoots with the anti-worker Cold War Hawke government. When the Polish government refused to allow Solidarnosc leader Lech Walesa leave to attend the 14th Congress of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) in Melbourne, the Labor Council directed 12 unions to ban postal deliveries, phone services, garbage collection, electrical, water and sewerage repairs, building maintenance and other services to the consulate from 3 March to the close of the conference on the 19th. These bans were war-like measures in the service of the imperialist anti-Soviet war drive, and all class-conscious workers should fight against them. Defend the USSR, Poland and all the workers states!35

The article was illustrated with a photo of Lech Walesa kissing a large crucifix.

By the end of the 1980s, Weyman’s political influence within the Polish community waned as Henryk Sikora (1952- ),36 a young, recent migrant then in his early 30s became more prominent. Funded by, with an office located within, the national office of the SDA from 1984-1991,37 Sikora was the Sydney-based chief of the Solidarity Information Bureau that was associated with the Brussels-based Solidarity representation overseas.38 By then, Weyman’s two key mentors in the FIA had departed the scene. Laurie Short retired in 1982. His successor as national secretary of the FIA, Harry Hurrell (1923-1988; Assistant National Secretary, FIA, 1951-1982, National Secretary, 1982-1988), died in 1988. Steve Harrison (1953-2014; National Secretary, FIA, 1988, then joint then sole National Secretary, Australian Workers Union, to 1997), who took over from Hurrell, was very sympathetic to Weyman and the causes he stood for, but both he and the union were consumed with organisational challenges associated with mergers, redundancy payments, structural change in declining manufacturing industries, and the fall in union membership. So Weyman was “let go”, but continued to hover around the union, seeking support and assistance for those who reached out to him. By 1989, with the collapse of communism and the emergence of a free Poland, so much of what Weyman had fought for was now within reach. He was aged 69.

Weyman was a ball of energy, intelligent, well informed, whom I greatly respected. When he challenged my favouring of English language skills in some of my public advocacy of immigration policy changes, I considered my position.

But I concluded that Australia could not take everyone and that migrants with English language skills would fit best into Australian society. Given that to some extent, always, immigration would be a controversial topic in future debates on the desirable intake, the ability to “fit in” would rank always highly as an issue. Hence, my insistence on English ability as an important selection criterion.

I see now that if the policy I favoured applied back in the day, Weyman and thousands of others who were denied access to education and skills development, with limited English, might never have been allowed to arrive on these shores.

There is always a personal element to the immigration story.

In revising this note, Adam Warzel, a former Victorian representative of the Solidarity Information Bureau and past President of the Australian Institute of Polish Affairs (AIPA), an independent, voluntary, non-political organisation founded in 1991 in Melbourne, emailed to say:

I knew Charles Weyman.

He lived in the ’50s in the same building in Warsaw as my uncle. When my mother visited me in 1986 (she came from Warsaw to Melbourne), we went to Sydney and met briefly with Weyman. My mum conveyed to him greetings from her brother. Charles was very moved.

As far as I recall, during the war Weyman rescued a Polish Jew by the name of Jerzy Krupiński [1920-2014],39 who became in the ’60s a notable mental health researcher in Melbourne. Krupiński is particularly well known for publishing a ground-breaking study on prevalence of schizophrenia in migrant communities in Australia. I also knew Weyman through my union/Solidarity connections. He was a principled and tough player. In 1988, the union he was associated with,40 cut off electricity connection to the Polish consulate in Sydney. They did it in response to the decision by the Polish communist authorities to bar Lech Walesa from attending International’s Union conference in Melbourne.41 He followed up to say: “Weyman was a doer, not a diplomat. He was strong-willed and effective in the way he was discharging his duties. But he could easily put off people he disagreed with. He was a good man.”42 Weyman’s gravestone records: “He devoted his life to others.”43

I am humbled that so much of the detail of what Charles Weyman did and achieved was unknown to me until writing this postscript.

NOTES:

1. An article in the Australian Jewish Times of 21 May 1981, incorrectly mentions that he was 57 at the time. The article, however, has a wealth of interesting biographical information. I am assuming that the spelling in Polish of his Germanic-sounding name would better approximate to Wejman. In the early part of the twentieth century, among Poles, Jews and non-Jews, it was not uncommon to hold German sounding names.

2. He is described as the loving husband to Mary, doting father to Christine and Camilla, father in law to Keith and Bernie, and the adored Poppy of Samantha, Vanessa, Krstianna and Chanelle, Daily Telegraph, 22 July 2003. His wife, Dr Marysia (“Mary”) Weyman (21 February 1924- 17 October 2007) died working at the desk of her medical practice at Croydon Park. Death Notice, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 September 2007. Her tombstone in the Catholic section of Rookwood cemetery, Sydney, reads: “A doctor who influenced everyone she encountered.”

3. Some of the history of those efforts in forging independent, Polish trade unions is told in Robert Zuzowski, Political Dissent and Opposition in Poland: The Workers’ Defense Committee “KOR”, Praeger Publishers, Westport (Connecticut, United States), 1992. I am grateful to Martin Krygier for this reference. Zuzowski notes that in November 1956 in the port of Gydia, near Gdansk, the Seamen’s and Deep-Sea Fishermen’s Trade Union was formed, though petered out after a year. (Ibid, p. 28.)

4. Ibid., p. 28

5. The Soviet leader gave his famous speech on ‘The Personality Cult and its Consequences’ in a closed session of the twentieth congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 February 1956.

6. I am alluding to the anti-Stalinist poem by the Polish writer Adam Ważyk (1905-1982), ‘Poem for Adults’ (1955) with its lines: “The dreamer Fourier beautifully prophesised/ that the sea would flow with lemonade./ And does it not flow?/ They drink sea-water,/ and cry –/ Lemonade!/ They return quietly home/ to vomit/ to vomit” – translation by Lucjan Blit. The full poem is reproduced in Paul E. Zinner, editor, National Communism and Popular Revolt in Eastern Europe. A Selection of Documents on Events in Poland and Hungary February-November 1956, Columbia University Press, New York, 1956, pp. 40-48.

7. Zuzowski, p. 24.

8. Charles Weyman, ‘Another Target for the Council of Churches?’ [Letter to the Editor], Sydney Morning Herald, 8 September 1977, p. 6.

9. Dymphna Cusack (1902-1981), novelist, playwright, “peace” activist, and friend of the Soviet Union and its satellites, most famous work is the novel Caddie, A Sydney Barmaid (1953) which was turned into a film in 1976.

10. Dymphna Cusack, ‘Impressed by Poland Today’ [Letter to the Editor], Sydney Morning Herald, 3 October 1977, p. 6.

11. Charles Weyman, ‘Polish Life Today’ [Letter to the Editor], Sydney Morning Herald, 10 October 1977, p. 6. Weyman signed the letter as Press Officer, Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association, Cabramatta Branch, Bareena Avenue, Cabramatta. Cusack testily replied saying that Weyman was bigoted and ignorant of the modern Poland and that she believed what she claimed.

12. For a memoir on his father, see Martin Krygier, ‘An Intimate and Foreign Affair’, in Ann Curthoys & Joy Damousi (editors), What Did You Do in the Cold War, Daddy?, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2014, pp. 23-55. On Short, see: Susanah Short, Laurie Short: A Political Life, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1992.

13. Laurie Short, ‘Lessons from Poland’, Labor News (New Series), Vol. 33, No. 248, July/August/September 1980, p. 8.

14. ‘FIA Invites Polish Solidarity Leader to Australia’, Labor News (New Series), Vol. 34, No. 251, February-March-April 1981, p. 1.

15. A copy of the recording is held at the Sydney Jewish Museum. Email: Tinny Lenthen (Sydney Jewish Museum) to Michael Easson, 12 February 2020.

16. From ‘The Righteous Among the Nations Database’, Yad Vashem, https://righteous.yadvashem.org/?search=Weyman&searchType=righteous_only&language=en&itemId=4018208&ind=0, accessed, 11 February 2020.

17. ‘Ethnic Affairs Officer Appointed’, Labor News (New Series), Vol. 38, No. 266 (New Series), May 1984, p. 3.

18. See: Barrie Unsworth, ‘Denial of Rights in Workers’ State’, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1979, p. 7; Andrew Casey, ‘Unionists Circulate Anti-Soviet Petition’, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 January 1980, p. 2. Paul Toplis from the Club Managers Association (a professional employees’ union) was the convenor. I helped write material based on reports from international union and human rights bodies, including Amnesty International. See: Paul Toplis, ‘Committee Campaigns for Union Rights [in Eastern Europe]’, Labor Leader [organ of Centre Unity, NSW ALP], Vol. 4, No. 1, p. 3.

19. Simone Lovett, ‘Bulgarian Family Reunited After Five Years’, Canberra Times, 18 January 1985, p. 7.

20. See photo and caption of Romanian hunger strikers at the Labor Council Building, Barrie Unsworth, Labor Council of New South Wales Annual Report and Auditors Report for 1981, Labor Council of NSW, Sydney, p. 24. Robert Dunn, ‘Union Shows Solidarity Over Dissident’, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 June 1987, p. 89. ‘Family Reunion’, Labor News, Vol. 38 No. 269 (New Series), November-December 1984, p. 2; ‘FIA Works for Family Reunions’, Labor News, Vol. 41, No. 278 (New Series), September-October 1986, p. 3.

21.‘Yugoslav Embassy Threat’, Canberra Times, 24 June 1987, p. 8. ‘Australian Goaled Illegally. Union Demands Release of Australian Serb’, Labor News, Vol. 42, No. 282, May-June-July 1987, p. 4; ‘The Pantelich Case — A Question of Human Rights’, Labor News, Vol. 42, No. 283 (New Series), August-September 1987, p. 2.

22. P.P. McGuinness, ‘The Decline of Unionism’, The Australian newspaper, 8 June 1989, reprinted in Padraic Pearce McGuinness, McGuinness. Collected Thoughts, Schwartz & Wilkinson, Melbourne, 1990, p. 205-207. McGuinness, in June 1989 was critical of the Labor Council of NSW’s garbage and other bans on the Chinese consulate in Sydney in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacres, and he linked this to earlier bans by the Labor Council on Eastern European consulates.

23. ‘FIA Works for Family Reunions’, Labor News (New Series), Vol. 41, No. 278, September-October 1986, p. 3.

24. Malcolm Brown, ‘Polish Defectors Get to Grip with a New Life’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 January 1982, p. 8.

25. Michnik, of Jewish Polish ancestry, was theoretical adviser in the mid-1970s to the Workers’ Defense Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników, KOR), a precursor and inspiration for efforts of Solidarność. KOR focused on aid to prisoners and their families after June 1976 protests and government crackdown. Michnik also advised Lech Wałęsa; imprisoned several times by the communist regime, he fell out with Walesa after Poland gained independence. He is founder and editor of Poland’s leading liberal newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, since 1989.

26. ‘NSW Labor Party Supports Polish Family Reunions’, Labor News, Vol. 36, No. 257 (New Series), May-June-July 1982, p. 1.

27. Jerzy Boniecki was a businessman and former Polish Commercial Consul in Sydney, who defected to Australia in 1963, and later assisted Poles settle in Australia. See: ‘The Boniecki Affair. Iron Curtain Migrants’, The Bulletin, Vol. 85, No. 4326, 12 January 1963.

28. Malgorzata Klatt, The Poles & Australia: A Partnership in Values, Australian Scholarly, North Melbourne, 2014, p. 68. For an account of support for Solidarność in Australia, which extensively mentions Weyman, see: Patryk Pleskot, Polska-Australia-Solidarność, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2014, https://www.academia.edu/29665988/POLSKA_AUSTRALIA_SOLIDARNOŚĆ_._Biografia_mówiona_Seweryna_Ozdowskiego, accessed, 9 February 2020.

29. Kim Christiaens, ‘The ICFTU and the WCL. The International Coordination of Solidarity’, in Idesbald Goddeeris, editor, Solidarity with Solidarity. Western European Trade Unions and the Polish Crisis, 1980-1982, Lexington Books, Lanham [Marylands, United States], 2010, p. 115.

30. See Labor Council of New South Wales Annual Report and Auditors Report for 1982, Labor Council, Sydney, 1982, pp. 8-9; Arkadiusz Kazański, Jerzy Milewski, Encyclopedia Solidarność, https://encysol.pl/es/encyklopedia/biogramy/17656,Milewski-Jerzy.html, accessed 11 March 2020. Oddly, in the Solidarity encyclopedia there is no reference to Wójcik. The duo were hugely influential in garnering western support for their cause, including the AFL-CIO (the American equivalent of the ACTU), and many western governments, including the Reagan administration.

31. Jerzy Milewski, Krzysztof Pomian, & Jan Zielonka, ‘Poland: Four Years After’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 64, No. 2, 1985/86; Timothy Garton Ash, The Polish Revolution: Solidarity, Yale University Press, New Haven, third edition, 2002, p. ix and supra; Gregory F. Domber, ‘The AFL-CIO, The Reagan Administration and Solidarność’,The Polish Review, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2007, pp. 277-304; Gregory F. Domber, Empowering Revolution: America, Poland, and the End of the Cold War, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2014, p. 307.

32. ‘Statement by NSW Labor Council Disputes Committee on Lech Walesa’, Labor News, Vol. 43, No. 286 (New Series), February-March-April 1988, p. 10.

33. Helen O’Neil, ‘Union Plan to Cut Off Polish Consulate’, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 February 1988, p. 5.

34. ‘Statement by NSW Labor Council Disputes Committee on Lech Walesa’, Labor News, Op. Cit.

35. ‘CIA Lovers Ban Polish Consulate’, the Australasian Spartacist, No. 125, April/May 1988, p. 2. See also, Malgorzata Klatt, The Poles & Australia, Op. Cit., p. 64, which references in a footnote the role of the Labor Council of NSW.

36. Monika Kobylańska, Henryk Sikora, Encyclopedia Solidarność, https://encysol.pl/es/encyklopedia/biogramy/17656,Milewski-Jerzy.html, accessed 19 February 2020.

37. When I asked Joe de Bruyn, the former National secretary of the SDA (who Sikora reported to) what were his memories of Weyman, Joe said he had never heard of him. Conversation, Michael Easson and Joe de Bruyn, 18 February 2020.

38. Email: Adam Warzel to Michael Easson, 12 February 2020.

39. A grandson of Krupiński, the management coach Peter Cook, wrote a brief memoir of his “dziadzia” (grandfather), https://petercook.com/blog/jerzy-krupinski-20021920-19032014-rip-dziadzia, accessed, 12 February 2020.

40. Actually, this was the Labor Council of NSW with the Electrical Trades Union, NSW Branch, and other unions who cut off electricity and other supplies.

41. Email: Adam Warzel to Michael Easson, 11 February 2020.

42. Email: Adam Warzel to Michael Easson, 13 February 2020.

43. He is buried with his wife at the Rookwood Catholic Cemeteries and Crematoria, Sydney.