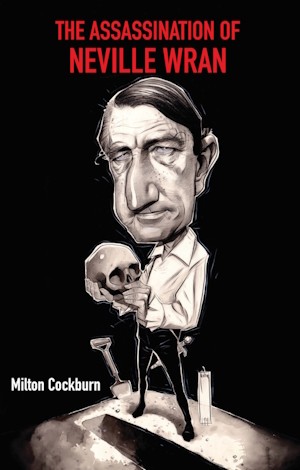

Review of Milton Cockburn, The Assassination of Neville Wran, Connor Court, 2024, published in Quadrant magazine, Volume 69, Number 3, March 2025.

The Assassination of Neville Wran is Milton Cockburn’s indignant rebuttal of corruption allegations against former NSW Premier Neville Wran AC QC (1926-2014; NSW Labor Premier 1976-86).

Cockburn complains: “Too often gossip passes for fact. This is exacerbated by… reporting …without any attempt at fact checking or corroboration.” He explains that because Australian defamation laws provide no recourse for the dead, journalists and others are less diligent in fact-checking claims against them. You can claim almost anything. But surely truth matters. The concluding line of his book is withering: “The character assassination of Neville Wran is mainly attributable to the media abandoning the moral responsibilities which once went hand-in-hand with legal privilege.”

Cockburn is a retired journalist, former Wran staffer in the early days of the NSW Premier’s ministerial advisory unit, past editor of The Sydney Morning Herald, and co-author with Mike Steketee of the 1986 critical biography Wran: An Unauthorised Biography. After leaving the Premier’s office in 1982, in The Sydney Morning Herald he fearlessly castigated the government for various policy failings. Cockburn was not personally close to Wran, never in the jump-seat next to the Premier.

In this work, Cockburn distils numerous stories of alleged suspect behaviour. Divided into eleven chapters, nine of which detail specific claims about the so-called ‘hidden’ crimes of Wran, Cockburn examines the evidence. The first and last chapters present issues to address and his conclusions.

Cockburn argues corruption is the use of power or influence for illegitimate private gain, usually in the form of money. A cover-up can only occur if a crime is committed. To those terms and standards, Cockburn stands his ground in assessing every allegation.

A brief note on Wran is warranted. He won four elections in a row in NSW, two in ‘Wranslides’. He was arguably the most popular political figure of any Australian state in the twentieth century. (At his zenith, NSW opinion polls recorded 80% approval ratings). After narrowly winning office in 1976, six months after the Whitlam government was dismissed, Wran’s government became the model for progressive, temperate Labor administrations across the country. To those who urged he should go faster, harder in political reform, he scoffed: “We’d be regarded as great social reformers if we cut our wrists with rusty razor blades like the Whitlam ministers did.”

Coming to office as a civil liberties lawyer, bereft of administrative experience, Wran’s judgement calls relied on instinct, worldly experience, and a gritty grasp of common sense. Wran’s belief that he was saddled with a weak ministry led him to centralise power in the Premier’s Department. He modelled NSW political governance on that of the first two-term NSW Labor administration, the McKell government, 1941-47.

Cockburn briefly presents arguments about solid reforms, but that is not the chief focus of the author’s work, which is about Wran’s posthumous reputation and character “assassination”.

The author does not sugar-coat Wran’s failings; the man was not made for sainthood. Cockburn cites Bob Carr’s remark that although he believes none of the corruption allegations, Wran’s handing of some matters sowed legitimate criticisms: Carr sees three distinct errors. First, the patronage and elevation of a corrupt cop, Bill Allen, as Assistant Police Commissioner. Second, the extension of the term of a man who turned out to be a corrupt NSW Chief Magistrate, Murray Farquhar, by the Wran Cabinet with the enthusiastic endorsement of the Premier. Third, being too slow to recognise and tackle police corruption. Additionally, the actions of one of Wran’s ministers, Rex Jackson, the minister responsible for NSW prisons, in accepting bribes for the early release of prisoners, tainted Wran’s premiership. (The minister was a gambler and ultimately imprisoned.) Carr says: “Almost every week I was to watch him struggle to ward off allegations that his administration was tainted by a laxness towards corruption.”

Cockburn argues that the NSW police were riddled with corruption when Wran came to office. The creation of an independent Police Board to assess candidates for senior ranks met with fierce resistance including strikes instigated by the NSW Police Association. Cockburn says Wran misjudged certain characters but was in no way compromised.

Cockburn pleas that untested evidence, especially ‘recollections’ suddenly coming to light decades later, ought to be critically and comprehensively evaluated, not gullibly accepted. Every investigative reporter hopes for a sensational, juicy expose. When a fabulous plum-in-a-napkin lands on your lap, the temptation is to shine and share the discovery. But even outstanding journalists, who have done great work exposing the faults and crimes of others, are not exempt from the obligation to appraise what might be too good to be true.

Some claims, credulously reported, are clearly from the imaginations of fantasists. For example: a one-time female consort of Abe Saffron, the ‘Mr Big’ crime boss of Sydney, claimed the NSW Premier regularly dropped in to Saffron’s house for Friday drinks. Another “witness” says the Premier picked up bribes from an illegal casino in Kings Cross. Another says that he saw Wran pop into a noted Potts Point eatery for lunch with Saffron in 1976. Yet the restaurant concerned opened six years later. Another daring ‘claim’ is that when CSIRO Chairman, Wran presided over the sale of land to a dodgy developer; but that sale occurred five years after Wran’s chairmanship.

Andrew Rule, a writer found wanting by Cockburn, described Wran as “bent as a three dollar note”, unfazed by the alchemistic feat this implied.

A common expression, “where there is smoke, there is fire”, suggests something suspicious to investigate. Retired Sydney University Government Professor Rodney Tiffen’s review of ABC Four Corners shows’ reporting of Wran is quoted by Cockburn, Tiffen says there is no evidence of personal corruption in the sense of Wran pursuing personal financial gain; but he suggests Wran was not held back by “procedural niceties” in rewarding friends. In that respect, Wran was a typical politician.

By far the most egregious allegations centred on claims in a three-part ABC 4 Corners ‘investigation’ and associated reporting, aired in March 2021, that in 1979 Wran nobbled a police investigation into a fire at Luna Park that killed six children and one adult. This chapter is mostly based on Cockburn’s 2021 article published in Quadrant, ‘The ABC Won’t Let Facts Ruin a Good Beat-Up’.

4 Corners alleged that Wran intervened to award the Luna Park lease to Abe Saffron. Yet Safron never owned or controlled, directly or indirectly, this lease. When the then NSW Police Minister Peter Anderson wanted a joint NSW and National Crime Authority (NCA) investigation of Saffron: “go for it, son” was Wran’s response. The then NSW Attorney-General, Terry Sheahan, with Wran’s instigation, got the Corporate Affairs Department and the NCA to investigate the shareholdings of the Luna Park leaseholder to see if there was any Saffron connection.

Cockburn states: “Despite the findings of the Corporate Affairs Commission and the [NCA] that Saffron had no ownership interest, the ABC journalists, with no apparent qualifications in the intricacies of corporate law and regulation, still told viewers that ‘the lease swung over to Abe Saffron’. The program could only make such an assertion by completely ignoring the evidence.”

Notably, Cockburn quotes Wran in the NSW Legislative Assembly in 1978, saying: “I do not know, I have never met, I have never eaten with, and I have never been in any circumstances with a gentleman named Abe Saffron.” There is no credible evidence before or later which qualifies what Wran said.

This book exhaustively interrogates new evidence and particulars of claims, including by Clarrie Briese, another former NSW Chief Magistrate; David Waterhouse, the estranged son of Bill Waterhouse, Wran’s friend from university days; by bit players and colourful police identities. Also evaluated is Wran’s business career with Malcolm Turnbull, which made Wran rich.

Cockburn draws on the unreported evidence presented to the Senate’s Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry established in 1986, but only made public in 2017, on allegations against then High Court Justice Lionel Murphy.

Cockburn vindicates the assessment of the Royal Commissioner, Sir Laurence Street, who completely exonerated Wran of corruption allegations in July 1983.

Crime author Andrew Rule claims: “Those who live by the sword have to expect a few whacks on their coffin lid.” Indeed. Cockburn forcibly wallops back on behalf of the dead. It is not tic for tac, though. Cockburn’s research compels him to vigorously contest nonsense claims. Margaret Simons excuses the excesses of Four Corners ‘journalism’, saying “the program’s most trenchant critics…[were] people who built their careers in the decade 1976-86”, when Wran was Premier. This ad hominem attack is excelled by Rule who says “…it looks too much as if they [Wran’s apologists] were either in on the Wran rorts or too dumb to realise that shifty Nifty had fooled them along with the voters.” Instead of tunnelling backwards in stunned shame, blithely accepting such coercive sanctimony, Cockburn insists on sifting truth from the evidence.

It is Cockburn’s achievement that ‘more in sorrow than anger’ is the moniker that applies to what he writes and castigates in others.

Postscript (2025)

I wrote this in October 2024 but then needed to find a publication to publish. Most grateful to Rebecca Weissner, editor of Quadrant for doing so.

I got this email from Paul Everingham, former Chief Minister of the Northern Territory:

Message: I read the review of your book on Neville Wran in the Quadrant magazine. Glad that you wrote it. I was NT Chief Minister at least part of the time he was Premier. He was always the soul of courtesy and helpful to a johnny from the sticks like me. Forums such as the Premiers Conference were terrifying to me as I went last in my presentations. Wran was always encouraging. I even knew Rex Jackson as he was NSW rep on the Federal Aboriginal Affairs Minsters’’ committee. He too was helpful. I was shocked when he was charged, and I caught up with him after he was released. He had a Mr Whippy van down at the lookout in the National Park. Will buy the book as I thought the Luna Park stuff was rubbish… Cheers Paul Everingham