Published in Recorder, official newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society, Issue No. 311, March 2025, pp. 8-10.

Many of us broadly familiar with John Curtin, admire his stance to defeat naysayers and introduce conscription for the defence of Australia during World War II.

Nick Dyrenfurth and Frank Bongiorno, in their A Little History of the Australian Labor Party (reviewed in these pages this issue of The Recorder), credit John Curtin for “maintaining party unity during these years” and getting the National Labor Conference to endorse “a proposal allowing conscripts to be sent outside Australian territory in the war against Japan.”

Those words drastically abbreviate, though, the strangeness of the debate within Australian Labor about conscription during Curtin’s prime ministership.

Background

On 3 September 1939, Australia declared war on Germany along with Great Britain and France, after Germany’s invasion of Poland. As an economy measure during the Great Depression, the Scullin Labor Government had suspended the Universal Training Scheme. In 1939 Australia had a permanent army of less than 4000 personnel. Its peacetime militia numbered about 80,000 men, mainly civilians serving on a part-time basis. The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) had 3500 men, though it lacked effective aircraft. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) had 5400 regulars, although its ships were few – effectively only two heavy cruisers and four light cruisers which were relatively modern.

On 20 October 1939 Prime Minister Menzies announced the reintroduction of compulsory military training, known as the Universal Service Scheme, with effect from 1 January 1940. The arrangements required unmarried men turning 21 to undertake three months’ training with the Citizen Military Forces (CMF). There was no conscription for service beyond the Australian mainland and its territories, which included Papua and New Guinea. The Labor Opposition voiced opposition, disagreeing with any overseas service, even for volunteers.

This marked a low point of Australian Labor’s complacency about the War and its implications for the defence of the nation.

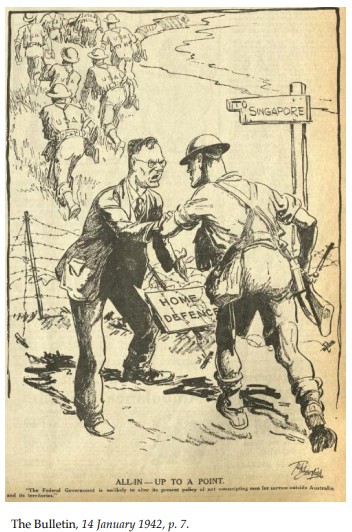

In 1939, the government raised a new volunteer army for service overseas. This was the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF). A concerted recruitment campaign, at a time of high unemployment led to the ranks filling rapidly. Effectively, there were two armies – the elite, well-trained AIF and the conscripts, the CMF troops. The latter were nicknamed ‘koalas’, a protected species that could not be exported.

Under Menzies, to assist British forces, Australia deployed most of the Second AIF in North Africa, Greece and the Syria-Lebanon campaign.

In October 1941, PM Menzies lost office when several independent MPs switched to support John Curtin. The new wartime PM faced immediate crises associated with the war effort.

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise, near-devastating attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour – the Day of Infamy in President Roosevelt’s speech. With Japan threatening Australia, Curtin had to demand that Australian troops in North Africa come home.

The War Hits Australia

As the threat of impending war with Japan grew, Australia despatched the AIF’s 8th Division, four RAAF squadrons and eight RAN warships to Singapore and Malaya. Most of the men in the 8th Division were hauled into captivity when Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. 15,000 Australians were in the haul of 130,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese.

In late December 1941, as the implications of Japanese aggression were considered, Curtin said “I demand that Australians everywhere realise that Australia is now inside the firing lines.” He further remarked: “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.”

On 19 February 1942, Darwin was bombed. Japanese fighters and bomber planes attacked the port and shipping in the harbour twice during the day, killing 252 (which was kept secret at the time).

In March 1942 US General MacArthur arrived in Australia from the Philippines having escaped the Japanese invasion. On his way to Adelaide on 11 March he quipped: “I came out of Bataan, and I shall return”. Curtin agreed with the request of President Roosevelt that the General be Supreme Commander of all allied forces in the Pacific.

From 31 May to 8 June 1942, Imperial Japanese Navy submarines made a series of attacks on Australian cities. Three Japanese ‘midget subs’ were launched targeting Sydney Harbour, one of which fired torpedoes at the cruiser USS Chicago. They missed, but one struck the barracks ship HMAS Kuttabul, killing 21 naval ratings.

In July 1942 began the seven-month Kokoda Trail campaign, to wrest New Guinea from Japanese forces based there.

In the defence of Australia, American conscripts were deployed in New Guinea, on Australian soil and beyond. Yet Australia dithered about implementing compulsory military service for its own able-bodied men.

Labor’s Conscription Debate

Within Australian Labor, Talmudic-like debate occurred as to what should be permissible. David Lodge, the English novelist wrote a wry novel about Catholic moral concerns in the more permissive 1960s, How Far Can You Go? The same title could have been deployed about the conscription debate within Labor in 1942-43.

From 4-8 May 1942 the naval Battle of the Coral Sea (1000km east of Queensland) took place, with the US determined to arrest Japanese control of the western Pacific Ocean and to thwart Japan’s invasion of Port Moresby. Advised that the battle had just commenced, in Parliament Curtin said: “As I speak, those who are participating in the engagement are conforming to the sternest discipline and are subjecting themselves with all they have — it may be for many of them the last full measure of their devotion — to accomplish the increased safety and security of this territory…” Many of the 543 Americans who were wounded or killed in that battle were conscripts. McMullin in his history of the ALP, The Light on the Hill, acknowledges “the sharp contrast between American conscripts coming so far to defend Australia and Australian conscripts being restricted to service in Australia and its nearby territories…”

By late 1942, the stakes were high; voluntary recruitment was waning. The CMF comprised some 262,000 troops, with the AIF around 171,000. In June 1942, at the Battle at Midway, the American navy inflicted heavy blows on the Japanese navy. The reversal of Japan’s fortunes had begun.

A chapter in the second volume of John Edwards’ masterful study, John Curtin’s War, is titled ‘A First-Class Political Crisis’. Towards the end of 1942 the war moved north of Papua New Guinea, to the Philippines, and potentially to Singapore and Malaya. Edwards says: “For Curtin, introducing conscription for overseas service in 1942 and 1943 was a tricky political task to which he applied fine professional skills. It was not a moral agony.”

By this stage of the war, it was clear that the defeat of Japan required deployment of Australian troops further north, along with the Americans. Despite his earlier opposition to conscription for overseas service, Curtin changed his mind.

Arthur Calwell bitterly opposed conscription. Part of the debate was how far beyond Australia and its immediate region should conscripts be required to serve – the ‘how far can they go’ argument.

Curtin proposed that the Defence Act be amended to include “such other territories in the South-west Pacific area as the Governor-General proclaims as territories associated with the defence of Australia.”

Calwell’s biographer, Colm Kiernan, quotes him saying in late 1942: “Behind all these schemes for conscripting manpower is the idea of introducing coloured labour into Australia.” Another of Curtin’s ministers, Eddie Ward, the Labour and National Service Minister, accused Curtin of “putting young men into the slaughterhouse”. With friends like these…

On 4 January 1943 the National ALP Conference voted 24-12 to support Curtin’s initiative The delegations from Queensland and Victoria voted against. Having deftly handled the party, his Cabinet, and the Caucus, Curtin oversaw the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943 passed by the House on 19 February 1943. The theatre known as the South-West Pacific Zone, covered not only Australia and Papua and New Guinea, and also extended to east Java, southern Borneo, Dutch New Guinea and various other islands up to the Equator.

Explanations of Australia’s position to Washington in the lead-up to that decision and even thereafter must have been delivered with blushing embarrassment. But that is another story.

Postscript (2025)

The editor added at the end of the article this useful point: [Ed: Those with a library subscription might also find Peter Love’s 1977 article of interest: “Curtin, Macarthur and conscription, 1942–43”, Historical Studies, 17(69), 505–511.